The Death of Liability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Over», L’Innocenza Quecento a Palazzo Vecchio - È Diventato Un Caso Giudiziario

GIOVEDÌ 8 DICEMBRE 2011 il manifesto pagina 13 VISIONI DACIA MARAINI ANDREA SEGRE Sono aperte le iscrizioni alla scuola di drammaturgia abruzzese diretta da Dacia Maraini, che il Nonostante le poche copie in distribuzione, al regista è stato consegnato il premio Fac alle 16 dicembre terrà la prima lezione assieme alla regista Emma Dante. Nata dall’Associazione Giornate Professionali di Cinema a Sorrento, per il film «Io sono li», e anche l’Asti Film Festival Teatro di Gioia, la scuola intende formare dei professionisti nel campo teatrale, dalla regia lo premia come miglior film. Per lanciare il nuovo film «Io voglio vedere», Segre chiede agli all’arte della clownerie. Le lezioni si terranno fino ad agosto, in diverse località abruzzesi. spettatori di compilare un modulo per fare pressione su esercenti e sale cinematografiche. SULMONACINEMA 29 · Vince «L’estate di Giacomo» di Alessandro Comodin ARTE · Leonardo diventa un caso giudiziario La ricerca della «Battaglia di Anghiari» - c’è una sonda che sta «lavorando» da diver- si giorni in una intercapedine di muro, dietro il dipinto del Vasari, nella Sala dei Cin- «Game over», l’innocenza quecento a Palazzo Vecchio - è diventato un caso giudiziario. Dopo l’esposto da parte di Italia Nostra, redatto insieme a un gruppo di intellettuali e studiosi (non solo italiani), la procura di Firenze ha aperto un fascicolo e avviato un’indagine. L’accusa è quella di aver danneggiato l’affresco vasariano (la «Battaglia di Scanna- selvaggia delle immagini gallo») con un procedimento considerato «avventato»: lo staff dell'ingegner Maurizio Seracini, dell'università di San Diego, avrebbe infatti introdotto la microcamera nel- l’opera stessa del pittore, per tentare di scovare il capolavoro del Leonardo perduto da secoli. -

Seminole-Tribune-July-30-2010.Pdf

Disc Golf Native Learning Center’s July 4 Celebrations Pool Party Summer Conference COMMUNITY v 8A and 9A SPORTS v 2C EDUCATION v 3B 7PMVNF999*t/VNCFS +VMZ Tribal Council Youth Conference in Orlando Teaches Children Vital Life Lessons Approves August BY CHRIS C. JENKINS *LUOV&OXE&RXQVHORUDQGFRQIHUHQFHFRRUJDQL]HU Staff Reporter ³7KLVZHHNLVDQH[DPSOHRIKRZZHWDNHWLPHRXWIRU our youth; they are our future. Spend time with them; Special Election ORLANDO ² 7KH DQQXDO +ROO\ZRRG 1RQ LWLVWKH,QGLDQZD\´ BY CHRIS C. JENKINS 5HVLGHQW)RUW3LHUFHDQG7UDLO6HPLQROH<RXWK&RQ- $V SHUHQQLDO JXHVW OHFWXUHUV IRU WKH FRQIHUHQFH Staff Reporter IHUHQFHEURXJKW\RXWKDQGWKHLUSDUHQWVWRJHWKHURQFH 9LOODORERVDQG(QJOLVKVDLGLQVWLOOLQJ1DWLYHSULGHDQG again with the goal of enlightening its future leaders in DUWLVWLFH[SUHVVLRQFRQWLQXHVWREHWKHLUPDLQPHVVDJH BIG CYPRESS — 7ULEDO&RXQFLOFRQ- WKHDUHDVRIFXOWXUHGUXJSUHYHQWLRQ¿QDQFHVHGXFD- HDFK\HDU YHQHGRQWKH%LJ&\SUHVV5HVHUYDWLRQ&RP- WLRQDUWKHDOWKDQGRWKHUHVVHQWLDOOLIHVW\OHWRSLFV ³,ZDQWWKHPWREHSURXGWREH,QGLDQ:KDWHYHULW PXQLW\&HQWHU-XO\DQGDQGDXWKRUL]HG 7KHFRPI\*D\ORUG3DOPV5HVRUWDQG&RQYHQWLRQ LVWKH\DUHWU\LQJWROHDUQLWZLOOKHOSWKHPWRNHHSWKHLU DVSHFLDOHOHFWLRQIRUWKH%LJ&\SUHVV7ULEDO &HQWHUVHUYHGDVKRPHEDVHWRGR]HQVZLWKWKH KHDGVKHOGKLJK´9LOODORERVVDLG³7KHUHDUHQRWDORW &RXQFLO5HSUHVHQWDWLYHVHDW WKHPHRI³3URVSHULW\7KURXJK3HUVHYHUDQFH´-XO\ RI1DWLYHUROHPRGHOVWRORRNXSWR:HKDYHWRVHWWKDW 7KH VSHFLDO HOHFWLRQ ZLOO WDNH SODFH 6HYHUDO JXHVWV DQG SUHVHQWHUV ZHUH IHDWXUHG H[DPSOH´ IURPDPWRSP$XJXVWDWWKH6H- WKURXJKRXWWKHZHHNLQFOXGLQJ7LIIDQ\6LQFODLUUHLJQ- ³,WLVDERXWLQVSLULQJ\RXQJSHRSOHWREHFUHDWLYH´ -

Newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 15/07 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 212 - September 2007 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 3 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 15/07 (Nr. 212) September 2007 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, schen und japanischen DVDs Aus- Nach den in diesem Jahr bereits liebe Filmfreunde! schau halten, dann dürfen Sie sich absolvierten Filmfestivals Es gibt Tage, da wünscht man sich, schon auf die Ausgaben 213 und ”Widescreen Weekend” (Bradford), mit mindestens fünf Armen und 214 freuen. Diese werden wir so ”Bollywood and Beyond” (Stutt- mehr als nur zwei Hirnhälften ge- bald wie möglich publizieren. Lei- gart) und ”Fantasy Filmfest” (Stutt- boren zu sein. Denn das würde die der erfordert das Einpflegen neuer gart) steht am ersten Oktober- tägliche Arbeit sicherlich wesent- Titel in unsere Datenbank gerade wochenende das vierte Highlight lich einfacher machen. Als enthu- bei deutschen DVDs sehr viel mehr am Festivalhimmel an. Nunmehr siastischer Filmfanatiker vermutet Zeit als bei Übersee-Releases. Und bereits zum dritten Mal lädt die man natürlich schon lange, dass Sie können sich kaum vorstellen, Schauburg in Karlsruhe zum irgendwo auf der Welt in einem was sich seit Beginn unserer Som- ”Todd-AO Filmfestival” in die ba- kleinen, total unauffälligen Labor merpause alles angesammelt hat! dische Hauptstadt ein. Das diesjäh- inmitten einer Wüstenlandschaft Man merkt deutlich, dass wir uns rige Programm wurde gerade eben bereits mit genmanipulierten Men- bereits auf das Herbst- und Winter- offiziell verkündet und das wollen schen experimentiert wird, die ge- geschäft zubewegen. -

Lessons from a Public Policy Failure: EPA and Noise Abatement

Lessons from a Public Policy Failure: EPA and Noise Abatement Sidney A. Shapiro* CONTENTS Introduction ................................................... 1 I. Noise Abatement in the United States ...................... 3 A. Noise Levels and Health and Welfare Consequences .... 4 B. The History of Noise Abatement ....................... 5 1. Noise Abatement Prior to ONAC .................. 6 2. Noise Abatement During ONAC ................... 9 3. Noise Abatement After ONAC ..................... 19 C. The Current Status of Noise Abatement ................ 30 II. The Future of Noise Abatement in the United States ........ 33 A. The Role of State and Local Involvement .............. 33 1. Why State and Local Regulation Declined .......... 34 2. The Importance of State and Local Involvement .... 39 3. Implications for Federal Policy ..................... 40 B. The Role of Federal Involvement ...................... 44 1. Congressional Options ............................. 44 2. EPA Options ...................................... 48 Conclusion ..................................................... 60 INTRODUCTION In early 1981, Charles Elkins, who headed the Office of Noise Abatement and Control (ONAC) at the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), received a surprise telephone call from EPA's Deputy Assistant Administrator, Ed Turk. Turk informed Elkins that the White House Office of Management and Budget (the OMB) had de- cided to end funding of ONAC and that the matter was nonnegotiable., Copyright © 1992 by ECOLOGY LAW QUARTERLY * Rounds Professor of Law, University of Kansas; J.D. 1973, B.S. 1970, University of Pennsylvania. This article is based on a report prepared for the Administrative Conference of the United States. Publication of the article is authorized by the Administrative Conference, but the au- thor is solely responsible for its contents. The author appreciates the comments of Alice Suter and acknowledges the assistance of Wesley Rish, class of 1991, University of North Carolina. -

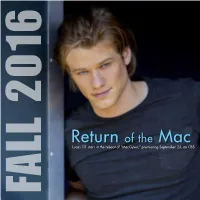

Return of The

Return of the Mac Lucas Till stars in the reboot of “MacGyver,” premiering September 23, on CBS. FALL 2016 FALL “Conviction” ABC Mon., Oct. 3, 10 p.m. PLUG IN TO Right after finishing her two-season run as “Marvel’s Agent Carter,” Hayley Atwell – again sporting a flawless THESE FALL PREMIERES American accent for a British actress – BY JAY BOBBIN returns to ABC as a smart but wayward lawyer and member of a former first family who avoids doing jail time by joining a district attorney (“CSI: NY” alum Eddie Cahill) in his crusade to overturn apparent wrongful convictions … and possibly set things straight with her relatives in the process. “American Housewife” ABC Tues., Oct. 11, 8:30 p.m. Following several seasons of lending reliable support to the stars of “Mike & Molly,” Katy Mixon gets the “Designated Survivor” ABC showcase role in this sitcom, which Wed., Sept. 21, 10 p.m. originally was titled “The Second Fattest If Kiefer Sutherland wanted an effective series follow-up to “24,” he’s found it, based Housewife in Westport” – indicating on the riveting early footage of this drama. The show takes its title from the term used that her character isn’t in step with the for the member of a presidential cabinet who stays behind during the State of the Connecticut town’s largely “perfect” Union Address, should anything happen to the others … and it does here, making female residents, but the sweetly candid Sutherland’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development the new and immediate wife and mom is boldly content to have chief executive. -

10 BOLD Aug 15

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 15th August 2021 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Bondi Rescue (Rpt) CC PG WS Mild Coarse Bondi Rescue follows the work of elite lifeguards patrolling the world's Language, Mature Themes, busiest beach. With people's lives literally in their hands these lifeguards Nudity ensure public safety is their number one priority. 08:30 am Reel Action (Rpt) CC G Seadoo Squid With Harbour Bream Guesty catches up with Brian Perry to try their luck in Newcastle harbour. Then, Guesty heads further north teaming up with young Curtis Chalker for one last crack at the mighty mulloway. 09:00 am Snap Happy (Rpt) CC G If you like photography then you'll love Snap Happy. This show will inspire and equip you to become a better photographer. 09:30 am Escape Fishing With ET (Rpt) CC G Escape with former Rugby League Legend "ET" Andrew Ettingshausen as he travels Australia and the Pacific, hunting out all types of species of fish, while sharing his knowledge on how to catch them. 10:00 am Bondi Rescue: Road Boss Rally (Rpt) CC PG Bondi Rescue: Road Boss Rally Coarse Language, The Bondi Rescue team Reidy, Corey & Whippet compete in the Mature Themes, Nudity legendary Road Boss Rally. -

DVD Profiler

101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure Animation Family Comedy2003 74 minG Coll.# 1 C Barry Bostwick, Jason Alexander, The endearing tale of Disney's animated classic '101 Dalmatians' continues in the delightful, all-new movie, '101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London A Martin Short, Bobby Lockwood, Adventure'. It's a fun-filled adventure fresh with irresistible original music and loveable new characters, voiced by Jason Alexander, Martin Short and S Susan Blakeslee, Samuel West, Barry Bostwick. Maurice LaMarche, Jeff Bennett, T D.Jim Kammerud P. Carolyn Bates C. W. Garrett K. SchiffM. Geoff Foster 102 Dalmatians Family 2000 100 min G Coll.# 2 C Eric Idle, Glenn Close, Gerard Get ready for outrageous fun in Disney's '102 Dalmatians'. It's a brand-new, hilarious adventure, starring the audacious Oddball, the spotless A Depardieu, Ioan Gruffudd, Alice Dalmatian puppy on a search for her rightful spots, and Waddlesworth, the wisecracking, delusional macaw who thinks he's a Rottweiler. Barking S Evans, Tim McInnerny, Ben mad, this unlikely duo leads a posse of puppies on a mission to outfox the wildly wicked, ever-scheming Cruella De Vil. Filled with chases, close Crompton, Carol MacReady, Ian calls, hilarious antics and thrilling escapes all the way from London through the streets of Paris - and a Parisian bakery - this adventure-packed tale T D.Kevin Lima P. Edward S. Feldman C. Adrian BiddleW. Dodie SmithM. David Newman 16 Blocks: Widescreen Edition Action Suspense/Thriller Drama 2005 102 min PG-13 Coll.# 390 C Bruce Willis, Mos Def, David From 'Lethal Weapon' director Richard Donner comes "a hard-to-beat thriller" (Gene Shalit, 'Today'/NBC-TV). -

Carol Raskin

Carol Raskin Artistic Images Make-Up and Hair Artists, Inc. Miami – Office: (305) 216-4985 Miami - Cell: (305) 216-4985 Los Angeles - Office: (310) 597-1801 FILMS DATE FILM DIRECTOR PRODUCTION ROLE 2019 Fear of Rain Castille Landon Pinstripe Productions Department Head Hair (Kathrine Heigl, Madison Iseman, Israel Broussard, Harry Connick Jr.) 2018 Critical Thinking John Leguizamo Critical Thinking LLC Department Head Hair (John Leguizamo, Michael Williams, Corwin Tuggles, Zora Casebere, Ramses Jimenez, William Hochman) The Last Thing He Wanted Dee Rees Elena McMahon Productions Additional Hair (Miami) (Anne Hathaway, Ben Affleck, Willem Dafoe, Toby Jones, Rosie Perez) Waves Trey Edward Shults Ultralight Beam LLC Key Hair (Sterling K. Brown, Kevin Harrison, Jr., Alexa Demie, Renee Goldsberry) The One and Only Ivan Thea Sharrock Big Time Mall Productions/Headliner Additional Hair (Bryan Cranston, Ariana Greenblatt, Ramon Rodriguez) (U. S. unit) 2017 The Florida Project Sean Baker The Florida Project, Inc. Department Head Hair (Willem Dafoe, Bria Vinaite, Mela Murder, Brooklynn Prince) Untitled Detroit City Yann Demange Detroit City Productions, LLC Additional Hair (Miami) (Richie Merritt Jr., Matthew McConaughey, Taylour Paige, Eddie Marsan, Alan Bomar Jones) 2016 Baywatch Seth Gordon Paramount Worldwide Additional Hair (Florida) (Dwayne Johnson, Zac Efron, Alexandra Daddario, David Hasselhoff) Production, Inc. 2015 The Infiltrator Brad Furman Good Films Production Department Head Hair (Bryan Cranston, John Leguizamo, Benjamin Bratt, Olympia -

Fall 05 Reporter.Qxd

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) (Ed.) Periodical Part NBER Reporter Online, Volume 2005 NBER Reporter Online Provided in Cooperation with: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Cambridge, Mass. Suggested Citation: National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) (Ed.) (2005) : NBER Reporter Online, Volume 2005, NBER Reporter Online, National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Cambridge, MA This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/61988 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), -

10 BOLD Aug 8

Firefox http://prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Repor... SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 08th August 2021 06:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 06:30 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:00 am Home Shopping (Rpt) Home Shopping 07:30 am Key Of David PG The Key of David, a religious program, covers important issues of today with a unique perspective. 08:00 am Bondi Rescue (Rpt) CC PG WS Nudity Bondi Rescue follows the work of elite lifeguards in charge at the world's busiest beach. With people's lives literally in their hands, these lifeguards ensure safety is their number one priority. 08:30 am Reel Action (Rpt) CC G Car Topper Murray Cod Inverell is renowned for its creeks and rivers all sporting a healthy population of murray cod. Ross Cannizzaro and Guesty go in search of the iconic murray cod casting paddle tail soft plastics. 09:00 am Snap Happy (Rpt) CC G If you like photography then you'll love Snap Happy. This show will inspire and equip you to become a better photographer. 09:30 am Star Trek: Voyager (Rpt) PG Darkling Mild Violence, The Doctor tries to improve his programming by incorporating traits Mature Themes from famous and historical people, but is overwhelmed by the dark sides of their personalities. Kes falls in love on an away mission Starring: Kate Mulgrew, Robert Beltran, Roxann Dawson, Robert Duncan McNeill 10:30 am Star Trek: Voyager (Rpt) PG Rise Mild Violence While on an away mission to help a planet being bombarded with asteroids, Neelix comes up with a dangerous plan to re-establish communication with Voyager. -

Argentina - Economic, Social” of the National Security Adviser's NSC Latin American Staff Files, 1974-77 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 1, folder “Argentina - Economic, Social” of the National Security Adviser's NSC Latin American Staff Files, 1974-77 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 1 of the National Security Adviser's NSC Latin American Staff Files, 1974-77 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library THE WHITE HOUSE W.\SHl~GTON July 19, 1974 .• Dear Fred: • Thank you for the report of your trip to Argentina to present United States' condolences upon the death of President Peron. The account of your activities and conversations you had there was o!__great. interest. I deeply appreciate your willingness to under • take this mission on such short notice. It is clear that you carried out your functions in a manner reflecting credit on yourself and on the United States. Honorable Frederick Dent Secretary of Commerce Washington, D. c. • \ NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION Presidential Libraries Withdrawal Sheet WITHDRAWAL ID 016165 REASON FOR WITHDRAWAL • • National security restriction TYPE OF MATERIAL • . -

Network Telivision

NETWORK TELIVISION NETWORK SHOWS: ABC AMERICAN HOUSEWIFE Comedy ABC Studios Kapital Entertainment Wednesdays, 9:30 - 10:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Katy Mixon as Katie Otto, Meg Donnelly as Taylor Otto, Diedrich Bader as Jeff Otto, Ali Wong as Doris, Julia Butters as Anna-Kat Otto, Daniel DiMaggio as Harrison Otto, Carly Hughes as Angela Executive producers: Sarah Dunn, Aaron Kaplan, Rick Weiner, Kenny Schwartz, Ruben Fleischer Casting: Brett Greenstein, Collin Daniel, Greenstein/Daniel Casting, 1030 Cole Ave., Los Angeles, CA 90038 Shoots in Los Angeles. BLACK-ISH Comedy ABC Studios Tuesdays, 9:00 - 9:30 p.m., returns Oct. 3 Cast: Anthony Anderson as Andre “Dre” Johnson, Tracee Ellis Ross as Rainbow Johnson, Yara Shahidi as Zoey Johnson, Marcus Scribner as Andre Johnson, Jr., Miles Brown as Jack Johnson, Marsai Martin as Diane Johnson, Laurence Fishburne as Pops, and Peter Mackenzie as Mr. Stevens Executive producers: Kenya Barris, Stacy Traub, Anthony Anderson, Laurence Fishburne, Helen Sugland, E. Brian Dobbins, Corey Nickerson Casting: Alexis Frank Koczaraand Christine Smith Shevchenko, Koczara/Shevchenko Casting, Disney Lot, 500 S. Buena Vista St., Shorts Bldg. 147, Burbank, CA 91521 Shoots in Los Angeles DESIGNATED SURVIVOR Drama ABC Studios The Mark Gordon Company Wednesdays, 10:00 - 11:00 p.m., returns Sept. 27 Cast: Kiefer Sutherland as Tom Kirkman, Natascha McElhone as Alex Kirkman, Adan Canto as Aaron Shore, Italia Ricci as Emily Rhodes, LaMonica Garrett as Mike Ritter, Kal Pennas Seth Wright, Maggie Q as Hannah Wells, Zoe McLellan as Kendra Daynes, Ben Lawson as Damian Rennett, and Paulo Costanzo as Lyor Boone Executive producers: David Guggenheim, Simon Kinberg, Mark Gordon, Keith Eisner, Jeff Melvoin, Nick Pepper, Suzan Bymel, Aditya Sood, Kiefer Sutherland Casting: Liz Dean, Ulrich/Dawson/Kritzer Casting, 4705 Laurel Canyon Blvd., Ste.