1947-1956 (English)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Racing Is Life. Anything Before Or After Is Just Waiting.'

Steve McQueen’s 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta Lusso recently went under the hammer at Christie’s in Monterey, offering another reminder of a man whose motoring exploits mirrored some of his most famous onscreen performances. Christopher Kanal pays tribute to a legendary car driven by a screen icon. Thegetaway n 16 August 2007, Steve McQueen’s 1963 Ferrari 250 GT Berlinetta McQueen was also an avid racing enthusiast, performing many of his Lusso went under the hammer at Christies. This remarkable car was own stunts, and at one time considered becoming a professional racing Obought by an anonymous owner, who placed his bid by phone, for driver. Two weeks after breaking an ankle in one bike race, he and co-driver a cool $2.31 million – nearly twice the estimated pre-sale price. The auction Peter Revson raced a Porsche 908/02 in the 12 Hours of Sebring, winning drew 800 people to the Monterey Jet Center in California and attracted their engine class and finishing second to Mario Andretti’s Ferrari by a spirited bidding according to Christie’s Rik Pike. margin of just 23 seconds. So begins another chapter in the life of one of McQueen’s favourite cars, which he drove for nearly a decade. McQueen’s Lusso inspires an almost fetish- like fascination, created from a potent blend of McQueen mythology and an ‘racing IS LIFE. insatiable desire for limited-edition 12-cylinder Ferraris. McQueen is dead 27 years but his iconic status has never been more assured. The Lusso is widely ANYTHING BEFORE acknowledged as Ferrari’s greatest aesthetic and engineering achievement. -

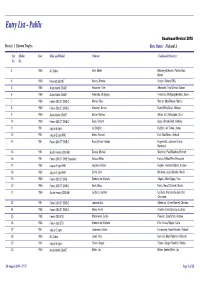

REV Entry List

Entry List - Public Goodwood Revival 2018 Race(s): 1 Kinrara Trophy - Race Status: National A Car Shelter Year Make and Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) No. No. 3 1963 AC Cobra Hunt, Martin Blakeney-Edwards, Patrick/Hunt, Martin 4 1960 Maserati 3500GT Rosina, Stefano Rosina, Stefano/TBC, 5 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Alexander, Tom Alexander, Tom/Wilmott, Adrian 6 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Friedrichs, Wolfgang Friedrichs, Wolfgang/Hadfield, Simon 7 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Werner, Max Werner, Max/Werner, Moritz 8 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Allemann, Benno Dowd, Mike/Gnani, Michael 9 1960 Aston Martin DB4GT Mosler, Mathias Gillian, G.C./Woodgate, Chris 10 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Gaye, Vincent Gaye, Vincent/Reid, Anthony 11 1961 Jaguar E-type Ian Dalglish Dalglish, Ian/Turner, James 12 1961 Jaguar E-type FHC Meins, Richard Huff, Rob/Meins, Richard 14 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Racing Team Holland Hugenholtz, John/van Oranje, Bernhard 15 1961 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Darcey, Michael Woolmer, Paul/Woolmer, Richard 16 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB 'Breadvan' Halusa, Niklas Halusa, Niklas/Pirro, Emanuele 17 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Hayden, Andrew Hayden, Andrew/Hibberd, Andrew 18 1962 Jaguar E-type FHC Corrie, John Minshaw, Jason/Stretton, Martin 19 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB Scuderia del Viadotto Vögele, Alain/Vögele, Yves 20 1960 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Devis, Marc Devis, Marc/O'Connell, Martin 21 1960 Austin Healey 3000 Mk1 Le Blanc, Karsten Le Blanc, Karsten/van Lanschot, Christiaen 23 1961 Ferrari 250 GT SWB/C Lanzante Ltd. Ellerbrock, Olivier/Glaesel, Christian -

Ferrari Club Del Ducato E Emilia-Romagnaemilia-Roma Gna

Incontro con le scuderie Ferrari Club del Ducato e Emilia-RomaEmilia-Romagnagna Informazioni e Iscrizioni CPAE CLUB PIACENTINO AUTOMOTOVEICOLI D’EPOCA Via Bressani, 8 29017 Fiorenzuola d’Arda (PC) 0523 248930 377 1695441 [email protected] - www.cpae.it HAL C LE A N V G O E R P C . .P.A.E Bobbio, 28 AGOSTO 2016 L ¡¢£¤¥¦§¨§¢ ©¥ ¤ ¥ ¥ § ¦ ©¥ ¤¥ § ©§¨§ ¦§ ¥ ¢ ¦ tuale ACI Piacenza) e del Podestà di Bobbio e vide il successo del Duca Lui- Programma raduno Ferrari gi Visconti di Modrone su Bugatti davanti a Gino Cavanna. Nella successiva 8:30-10:00 Accoglienza nel parcheggio di via di Corgnate B ! "# $enice I edizione s’impose il toscano Clemente Biondetti su Bugatti nei confronti del (parte superiore) e verifiche presso ufficio turistico N 1929 L.Visconti di Modrone, Bugatti 35 bolognese Amedeo Ruggeri su Maserati. La terza ed ultima edizione del pe- 10:45 Accodamento alle vetture del primo gruppo 1930 Clemente Biondetti, Bugatti 35 M riodo pionieristico registrò il successo di Enzo Ferrari su Alfa Romeo 2300 e arrivo al Passo Penice K 1931 Enzo Ferrari, Alfa Romeo 8C 2300 sport. E fu il “canto del cigno” del campione modenese che doveva diventare 11:30 Sosta in Piazzale Enzo Ferrari e aperitivo J 1952 Gianni Cavallini, Fiat 500/C il “Drake” di Maranello. La gara riprese negli anni 1952 e 1953 con la formula 12:00 Prova culturale e rientro a Bobbio 1953 Giacomo Parietti, Fiat 500/S mista velocità e regolarità. Nel ‘54 la corsa si effettuò con la formula che l’ha 12:30 Esposizione vetture in piazza Duomo e pranzo I 1954 Camillo Luglio, Lancia Aurelia B20 16:00 Premiazioni sempre contraddistinta e cioè quella del miglior tempo impiegato e fu il ge- H 1961 Gianni Brichetti, W.R.E. -

1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review

1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review The year was 1935 when the Jaguar brand first leapt out of the factory gates. Founded in 1922 as the Swallow Sidecar Company by William Lyons and William Walmsley, both were motorcycle enthusiasts and the company manufactured motorcycle sidecars and automobile bodies. Walmsley was rather happy with the company’s modest success and saw little point in taking risks by expanding the firm. He chose to spend more and more time plus company money on making parts for his model railway instead. Lyons bought him out with a public stock offering and became the sole Managing Director in 1935. The company was then renamed to S.S. Cars Limited. After Walmsley had left, the first car to bear the Jaguar name was the SS Jaguar 2.5l Saloon released in September 1935. The 2.5l Saloon was one of the most distinctive and beautiful cars of the pre-war era, with its sleek, low-slung design. It needed a new name to reflect these qualities, one that summed up its feline grace and elegance with such a finely-tuned balance of power and agility. The big cat was chosen, and the SS Jaguar perfectly justified that analogy. A matching open-top two-seater called the SS Jaguar 100 (named 100 to represent the theoretical top speed of 100mph) with a 3.5 litre engine was also available. www.themodelcarcritic.com | 1 1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review 1935 SS Jaguar 2.5l Saloon www.themodelcarcritic.com | 2 1:18 CMC Jaguar C-Type Review 1936 SS Jaguar 100 On 23rd March 1945, the shareholders took the initiative to rename the company to Jaguar Cars Limited due to the notoriety of the SS of Nazi Germany during the Second World War. -

Your Essential Guide to Le Mans 2011

Your essential guide to Le Mans 2011 Go and experience GT racing at the best race track in the world! Nurburgring 24 Hours 23rd - 26th June 2011 • Exclusive trackside camping • From £209.00 per person (based on two people in a car) Including channel crossings, four nights camping, general entrance ticket, including access to the paddock, grid walk and all open grandstands To book or for more information please call us now on 0844 873 0203 www.traveldestinations.co.uk Contents Welcome 02 Before you leave home and driving in France 03 Routes to the circuit from the channel ports 04 Equipment check-list and must-take items 12 On-Circuit camping description and directions 13 Off-Circuit camping and accommodation description and directions 16 The Travel Destinations trackside campsite at Porsche Curves 19 The Travel Destinations Flexotel Village at Antares Sud 22 Friday at Le Mans 25 Circuit and campsites map 26 Grandstands map 28 Points of interest map 29 Bars and restaurants 30 01 Useful local information 31 Where to watch the action 32 2011 race schedule 33 Le Mans 2011 Challengers 34 Teams and car entry list 36 Le Mans 24 Hours previous winners 38 Car comparisons 40 Dailysportscar.com join forces with Travel Destinations 42 Behind the scenes with Radio Le Mans at the 2010 Le Mans 24 Hours 44 On-Circuit assistance helpline 46 Emergency telephone numbers 47 Welcome to the Travel Destinations essential guide to Le Mans 02 24 Hours 2011 Travel Destinations is the UK’s leading tour operator for the Le Mans 24 Hours race and Le Mans Classic. -

Alo-Decals-Availability-And-Prices-2020-06-1.Pdf

https://alodecals.wordpress.com/ Contact and orders: [email protected] Availability and prices, as of June 1st, 2020 Disponibilité et prix, au 1er juin 2020 N.B. Indicated prices do not include shipping and handling (see below for details). All prices are for 1/43 decal sets; contact us for other scales. Our catalogue is normally updated every month. The latest copy can be downloaded at https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. N.B. Les prix indiqués n’incluent pas les frais de port (voir ci-dessous pour les détails). Ils sont applicables à des jeux de décalcomanies à l’échelle 1:43 ; nous contacter pour toute autre échelle. Notre catalogue est normalement mis à jour chaque mois. La plus récente copie peut être téléchargée à l’adresse https://alodecals.wordpress.com/catalogue/. Shipping and handling as of July 15, 2019 Frais de port au 15 juillet 2019 1 to 3 sets / 1 à 3 jeux 4,90 € 4 to 9 sets / 4 à 9 jeux 7,90 € 10 to 16 sets / 10 à 16 jeux 12,90 € 17 sets and above / 17 jeux et plus Contact us / Nous consulter AC COBRA Ref. 08364010 1962 Riverside 3 Hours #98 Krause 4.99€ Ref. 06206010 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #50 Miles 5.99€ Ref. 06206020 1963 Canadian Grand Prix #54 Wietzes 5.99€ Ref. 08323010 1963 Nassau Trophy Race #49 Butler 3.99€ Ref. 06150030 1963 Sebring 12 Hours #11 Maggiacomo-Jopp 4.99€ Ref. 06124010 1964 Sebring 12 Hours #16 Noseda-Stevens 5.99€ Ref. 08311010 1965 Nürburgring 1000 Kms #52 Sparrow-McLaren 5.99€ Ref. -

Petersen Automotive Museum Celebrates Pininfarina with New Exhibit

MARCH 2021/PRESS RELEASE PETERSEN AUTOMOTIVE MUSEUM CELEBRATES PININFARINA WITH NEW EXHIBIT “The Aesthetic of Motoring: 90 Years of Pininfarina” will showcase the diversity and versatility of the coachbuilder’s designs through four milestone examples – the 1931 Cadillac Model452A Boattail Roadster, 1947 Cisitalia 202 Coupe, 1966 Dino Berlinetta 206 GT Prototype and 2019 Automobili Pininfarina “Battista” Design Model Los Angeles, March 23 2021 – The Petersen 206 GT Prototype, the first mid-engine Ferrari; and Automotive Museum in Los Angeles will debut a 2019 Automobili Pininfarina “Battista”, which is a new exhibit celebrating Italian design firm and an early design model of the luxury hypercar rather coachbuilder Pininfarina on March 25. Located in the than a functioning automobile. A 1967 Ferrari 365P Armand Hammer Foundation Gallery, “The Aesthetic Berlinetta Speciale “Tre Posti,” the last vehicle bodied of Motoring: 90 Years of Pininfarina” will convey the by Pininfarina for a private client, will replace the 1966 significance and evolution of the Italian car design firm Dino Berlinetta 206 GT Prototype in April 2021. and coachbuilder through a curated display of four key automobiles representing its storied 90-year history. “With its commitment to elegant, aerodynamic design and small-scale production, Pininfarina has created Vehicles on display will include a 1931 Cadillac some of the most innovative and revered car designs Model452A Boattail Roadster, the first Pininfarina in the history of the automobile,” said Petersen body mounted -

Audi Repeats Last Year's Sebring Victory Quotes After the Race

Sebring, 18 March 2001 Audi repeats last year’s Sebring victory Audi had a successful dress rehersal for the 24 Hour Race at Le Mans: For the second time in a row Team Audi Sport North America took a 1-2 victory at the 12 Hours of Sebring (USA). Michele Alboreto, Laurent Aiello and Rinaldo Capello finished the race just 0.482s ahead of their team mates and last year’s winners Frank Biela, Tom Kristensen and Emanuele Pirro. The Audi customer teams of Champion and Johansson even made it the first 1-2-3-4 victory of Audi in the American Le Mans Series (ALMS) finishing 3rd and 4th. In front of a record crowd of 168,000 spectators, the two Infineon Audi R8s were setting the pace from the start on a track which is famous for being very demanding. The two customer R8s, however, stayed close making the pace among the leaders extremely fast. The two Infineon Audi R8s were fighting for victory for the whole twelve hour distance. Despite the enormous strain, the cars did not suffer from any severe difficulties. The Infineon Audi R8 #1 just had its front brake discs replaced shortly after half distance, the companion car had two pit stops because of a malfunction in the engine’s electrics. For the Audi crew the dress rehersal for Le Mans, however, is not completely over: On Monday and Tuesday the torture of another full 12- hour-distance is on the schedule for one of the two successful Infineon Audi R8s. Quotes after the race Laurent Aiello (#1): “It was a very tough race. -

The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN by Michael Browning

The Formula 1 Porsche displayed an interesting disc brake design and pioneering cooling fan placed horizontally above its air-cooled boxer engine. Dan Gurney won the 1962 GP of France and the Solitude Race. Thereafter the firm withdrew from Grand Prix racing. The Porsche Collection Phillip Island Classic PORSCHES GREATEST HITS PLAY AGAIN By Michael Browning Rouen, France July 8th 1962: It might have been a German car with an American driver, but the big French crowd But that was not the end of Porsche’s 1969 was on its feet applauding as the sleek race glory, for by the end of the year the silver Porsche with Dan Gurney driving 908 had brought the marque its first World took the chequered flag, giving the famous Championship of Makes, with notable wins sports car maker’s new naturally-aspirated at Brands Hatch, the Nurburgring and eight cylinder 1.5 litre F1 car its first Grand Watkins Glen. Prix win in only its fourth start. The Type 550 Spyder, first shown to the public in 1953 with a flat, tubular frame and four-cylinder, four- camshaft engine, opened the era of thoroughbred sports cars at Porsche. In the hands of enthusiastic factory and private sports car drivers and with ongoing development, the 550 Spyder continued to offer competitive advantage until 1957. With this vehicle Hans Hermann won the 1500 cc category of the 3388 km-long Race “Carrera Panamericana” in Mexico 1954. And it was hardly a hollow victory, with The following year, Porsche did it all again, the Porsche a lap clear of such luminaries this time finishing 1st, 2nd, 4th and 5th in as Tony Maggs’ and Jim Clark’s Lotuses, the Targa Florio with its evolutionary 908/03 Graham Hill’s BRM. -

Marques De Portago

La aristocracia en el automovilismo: El marqués Alfonso de Portago Entre las curiosidades de la historia del automovilismo, encontramos en ciertas ocasiones, la presencia de personalidades extravagantes, como lo fueron los aristócratas, pilotos de sangre azul. Entre ellos encontramos hacia los años 50 al marqués de Portago, cuyo nombre completo era Alfonso Antonio Vicente Eduardo Angel Blas Francisco Borja Cabeza de Vaca y Leighton, quien había nacido en Londres en 1928 y fue apadrinado por el rey Alfonso XIII de España. Su trayectoria en el automovilismo no fue muy extensa, ya que debutó en 1953, y murió en un accidente en 1957. No obstante, y a pesar de que no era un piloto demasiado efectivo, conquistó algunas victorias, mayormente compitiendo con Ferrari. Al principio, participó de carreras como copiloto, debutando en la carrera Panamericana de México en 1953, aunque poco después competiría él en otros autos, sin problema alguno para adquirirlos, dada su estirpe noble y su riqueza. Disputó pocas carreras en F1, pero participó en competencias de coches sport, de larga duración, como las 24 horas de Le Mans, y la Mille Miglia. Anduvo también por Argentina, participando en los 1000 kms. de la ciudad de Buenos Aires. Si había algo que caracterizaba al noble español, esto era ser un gran velocista, aunque en muchas ocasiones no terminaba las carreras por su ímpetu. No obstante, triunfó en una carrera para coches no oficiales en las islas Bahamas, sobre una Ferrari 750 Monza que había adquirido, para luego obtener un segundo puesto en ese mismo sitio. El marqués de Portago siempre fue admirador de los Ferrari, aunque tardó en convencer a don Enzo para que lo contrate como piloto. -

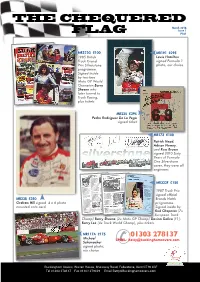

The Chequered Flag

THE CHEQUERED March 2016 Issue 1 FLAG F101 MR322G £100 MR191 £295 1985 British Lewis Hamilton Truck Grand signed Formula 1 Prix Silverstone photo, our choice programme. Signed inside by two-time Moto GP World Champion Barry Sheene who later turned to Truck Racing, plus tickets MR225 £295 Pedro Rodriguez De La Vega signed ticket MR273 £100 Patrick Head, Adrian Newey, and Ross Brawn signed 2010 Sixty Years of Formula One Silverstone cover, they were all engineers MR322F £150 1987 Truck Prix signed official MR238 £350 Brands Hatch Graham Hill signed 4 x 6 photo programme. mounted onto card Signed inside by Rod Chapman (7x European Truck Champ) Barry Sheene (2x Moto GP Champ) Davina Galica (F1), Barry Lee (4x Truck World Champ), plus tickets MR117A £175 01303 278137 Michael EMAIL: [email protected] Schumacher signed photo, our choice Buckingham Covers, Warren House, Shearway Road, Folkestone, Kent CT19 4BF 1 Tel 01303 278137 Fax 01303 279429 Email [email protected] SIGNED SILVERSTONE 2010 - 60 YEARS OF F1 Occassionally going round fairs you would find an odd Silverstone Motor Racing cover with a great signature on, but never more than one or two and always hard to find. They were only ever on sale at the circuit, and were sold to raise funds for things going on in Silverstone Village. Being sold on the circuit gave them access to some very hard to find signatures, as you can see from this initial selection. MR261 £30 MR262 £25 MR77C £45 Father and son drivers Sir Jackie Jody Scheckter, South African Damon Hill, British Racing Driver, and Paul Stewart. -

The Last Road Race

The Last Road Race ‘A very human story - and a good yarn too - that comes to life with interviews with the surviving drivers’ Observer X RICHARD W ILLIAMS Richard Williams is the chief sports writer for the Guardian and the bestselling author of The Death o f Ayrton Senna and Enzo Ferrari: A Life. By Richard Williams The Last Road Race The Death of Ayrton Senna Racers Enzo Ferrari: A Life The View from the High Board THE LAST ROAD RACE THE 1957 PESCARA GRAND PRIX Richard Williams Photographs by Bernard Cahier A PHOENIX PAPERBACK First published in Great Britain in 2004 by Weidenfeld & Nicolson This paperback edition published in 2005 by Phoenix, an imprint of Orion Books Ltd, Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin's Lane, London WC2H 9EA 10 987654321 Copyright © 2004 Richard Williams The right of Richard Williams to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 0 75381 851 5 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives, pic www.orionbooks.co.uk Contents 1 Arriving 1 2 History 11 3 Moss 24 4 The Road 36 5 Brooks 44 6 Red 58 7 Green 75 8 Salvadori 88 9 Practice 100 10 The Race 107 11 Home 121 12 Then 131 The Entry 137 The Starting Grid 138 The Results 139 Published Sources 140 Acknowledgements 142 Index 143 'I thought it was fantastic.