In Defense of Craft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Hermeneutics

JAPANESE HERMENEUTICS CURRENT DEBATES ON AESTHETICS AND INTERPRETATION EDITED BY MICHAEL F. MARRA JAPANESE HERMENEUTICS JAPANESE HERMENEUTICS CURRENT DEBATES ON AESTHETICS AND INTERPRETATION EDITED BY MICHAEL F. MARRA University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2002 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 07 06 05 04 03 02 654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Japanese hermeneutics : current debates on aesthetics and interpretation / edited by Michael F. Marra. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8248-2457-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Aesthetics, Japanese. 2. Hermeneutics. 3. Japanese literature— History and criticism. I. Marra, Michele. BH221.J3 J374 2000 111Ј.85Ј0952—dc21 2001040663 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by Carol Colbath Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Volano gli angeli in Paradiso Che adornano con il sorriso Nel ricordo di Gemmina (1960 –2000) CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction Michael F. Marra 1 HERMENEUTICS AND JAPAN 1. Method, Hermeneutics, Truth Gianni Vattimo 9 2. Poetics of Intransitivity Sasaki Ken’ichi 17 3. The Hermeneutic Approach to Japanese Modernity: “Art-Way,” “Iki,” and “Cut-Continuance” O¯ hashi Ryo¯suke 25 4. Frame and Link: A Philosophy of Japanese Composition Amagasaki Akira 36 5. The Eloquent Stillness of Stone: Rock in the Dry Landscape Garden Graham Parkes 44 6. Motoori Norinaga’s Hermeneutic of Mono no Aware: The Link between Ideal and Tradition Mark Meli 60 7. Between Individual and Communal, Subject and Object, Self and Other: Mediating Watsuji Tetsuro¯’s Hermeneutics John C. -

Kigo-Articles.Pdf

Kigo Articles Contained in the All-in-One PDF 1) Kigo and Seasonal Reference: Cross-cultural Issues in Anglo- American Haiku Author: Richard Gilbert (10 pages, 7500 words). A discussion of differences between season words as used in English-language haiku, and kigo within the Japanese literary context. Publication: Kumamoto Studies in English Language and Literature 49, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan, March 2006 (pp. 29- 46); revised from Simply Haiku 3.3 (Autumn 2005). 2) A New Haiku Era: Non-season kigo in the Gendai Haiku saijiki Authors: Richard Gilbert, Yûki Itô, Tomoko Murase, Ayaka Nishikawa, and Tomoko Takaki (4 pages, 1900 words). Introduction to the Muki Saijiki focusing on the muki kigo volume of the 2004 the Modern Haiku Association (Gendai Haiku Kyôkai; MHA). This article contains the translation of the Introduction to the volume, by Tohta Kaneko. Publication: Modern Haiku 37.2 (Summer 2006) 3) The Heart in Season: Sampling the Gendai Haiku Non-season Muki Saijiki – Preface Authors: Yûki Itô, with Richard Gilbert (3 pages, 1400 words). An online compliment to the Introduction by Tohta Kaneko found in the above-referenced Muki Saijiki article. Within, some useful information concerning the treatments of kigo in Bashô and Issa. Much of the information has been translated from Tohta Kaneko's Introduction to Haiku. Publication: Simply Haiku Journal 4.3 (Autumn 2006) 4) The Gendai Haiku Muki Saijiki -- Table of Contents Authors: Richard Gilbert, Yûki Itô, Tomoko Murase, Ayaka Nishikawa, and Tomoko Takaki (30 pages, 9300 words). A bilingual compilation of the keywords used in the Muki Saijiki Table of Contents. -

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2010 the Death of Kobayashi Yagobei

EARLY MODERN JAPAN 2010 5 The Death of Kobayashi Yagobei since. At some point before he had reached the ©Scot Hislop, National University of Singapore pinnacle of haikai rankings, Issa wrote an account, now called Chichi no shūen nikki (父の終焉日記: Introduction A Diary of my Father’s Final Days), of his father’s illness, death, and the first seven days of the fam- It is an accident of literary history that we know ily’s mourning. anything about Kobayashi Yagobei. His death, on Chichi no shūen nikki, as it has come down to the twentieth day of the 5th month of 1801 (Kyōwa us, is a complex text. Some parts of it have been 1) in Kashiwabara village, Shinano Province,1 was discussed in English language scholarship at least 6 important to his family. But Yagobei was not John F. since Max Bickerton’s 1932 introduction to Issa Kennedy, Matsuo Bashō,2 or even Woman Wang.3 and it is often treated as a work of literature or a 7 Yagobei’s death was the quotidian demise of some- diary. This approach to Chichi no shūen nikki one of no historical importance. However his eldest owes a great deal to the work of Kokubungaku 8 son, Yatarō, became Kobayashi Issa.4 In the years (Japanese National Literature) scholars. However, following his father’s death, Issa became one of the in order to read Chichi no shūen nikki as a book two or three most famous haikai (haiku) poets of within the canon of Japanese National Literature his generation and his renown has not diminished (Kokubungaku), it must be significantly trans- formed in various ways and a large portion of it is 1 The part of Shinano Town closest to Kuro- hime train station in Nagano Prefecture. -

Santoka :: Grass and Tree Cairn

Santoka :: Grass and Tree Cairn translations :: Hiroaki Sato illustrations :: Stephen Addiss Santoka :: Grass and Tree Cairn Translations by Hiroaki Sato Illustrations by Steven Addiss Back Cover Illustration by Kuniharu Shimizu <http://www.mahoroba.ne.jp/~kuni/haiga_gallery/> RE D ©2002 by Red Moon Press MOON ISBN 1-893959-28-7 PRESS Red Moon Press PO Box 2461 Winchester VA 22604-1661 USA [email protected] Santoka :: Grass and Tree Cairn translations :: Hiroaki Sato illustrations :: Stephen Addiss Taneda Santoka (1882-1940) was born a son of a large landowner in Yamaguchi and named Shoichi; mother committed suicide when he was ten; dropped out of Waseda University, Tokyo, after a nervous breakdown; started a sake brewery at 25; married at 27; acquired the habit of drinking heavily at 28; first haiku appeared in Ogiwara Seisensui’s non-traditional haiku magazine Soun (Cumulus) at age 31; moved to Kumamoto with family and started a secondhand bookstore when 34; legally divorced at 38; while in Tokyo, was arrested and jailed in the aftermath of the Great Kanto Earthquake, in 1923 (police used the quake as a pretext for rounding up and killing many Socialists); back in Kumamoto, taken to a Zen temple of the Soto sect as a result of drunken behavior at 42; ordained a Zen monk at 43; for the rest of his life was mostly on the road as a mendicant monk (in practical terms, a beggar), traveling throughout Japan; at 53, attempted suicide; his book of haiku Somokuto (Grass and Tree Cairn)—an assemblage of earlier chapbooks—was published several months before he died of a heart attack while asleep drunk; the book’s dedication was “to my mother / who hastened to her death when young”; Santoka, the penname he began to use when he translated Turgenev, means “mountaintop fire”. -

Santoka's Shikoku

Santōka’s Shikoku An introduction to and translation of the opening sections of the Shikoku Henro Diary of Japanese free-verse haiku poet and itinerant Buddhist priest Taneda Santōka (1882-1940) Ronald S. Green, Coastal Carolina University Of the many literary figures associated with Shikoku, Japan and the Buddhist pilgrimage to the 88 temples around the perimeter of that island, Taneda Santōka is the most visible to pilgrims and the one most associated with their sentiments. According to the newspaper Asahi Shinbun, each year 150,000 people embark on the Shikoku pilgrimage by bus, train, automobile, bicycles, or walking. Among these, nearly all the foreign visitors make the journey on foot, spending weeks or months on the pilgrimage. Those walking are likely to encounter the most poetry steles (kuhi) that display the works of Taneda Santōka (1882-1940) and commemorate his life and pilgrimage in Shikoku. This is because some of the kuhi are located halfway up steep stairway ascents to temples or at entrances to narrow mountain paths, places Santōka loved. This paper introduces English readers to Santōka’s deep connection with Shikoku. This will become increasingly important as the Shikoku pilgrimage moves closer to becoming a UNESCO World Heritage site and the prefectures eventually achieve that goal. Santōka was an itinerant Buddhist priest, remembered mostly for his gentle nature that comes through to readers of his free-verse haiku. Santōka is also known for his fondness of Japanese sake, which eventually contributed to his death in Shikoku at the age of 58. Santōka lived at a time when Masaoka Shiki was innovating haiku by untying it from some of the classical rules that young poets were finding to be a hindrance to their expressions. -

An Introduction to the Haiku of Taneda Santoka by Stanford M. Forrester

http://www.poetrysociety.org.nz/forresteronsantoka A bowl of rice: An Introduction to the Haiku of Taneda Santoka by Stanford M. Forrester The reason I chose to write a paper on Taneda Santoka is that he is a very important poet in modern haiku literature, but he is not very well known within the English language haiku community, which is unfortunate. Therefore, what I plan to do in this paper is to discuss various aspects of Santoka's life and his poetry, and hope to address some of the questions that may arise from this discussion. Taneda Santoka was born in 1882 and died in 1940. He was 58 years old. Of these 58 years, Santoka spent 16 of them as a mendicant Zen priest. As James Abrams points out in his article "Hail in the Begging Bowl", Santoka most likely was in Japan the last in line of priest-poets. What is different, however, about Santoka compared to Basho, Issa, Ryokan, Saigyo, or Dogen, is that he did not follow the traditional conventions of the poetic form in which he worked. Santoka was a disciple of Ogiwara Seisensui (1884-1976), the leader of the " free-style school of haiku". This school of haiku discarded the traditional use of the season word and the 5-7-5 structure. Instead it opted for a freer verse form. John Stevens, in his book Mountain Tasting, explains that after Shiki's death in 1902, "there became two main streams in the haiku world, one working more or less in a traditional form using modern themes and the other which fell under the 'new development movement.'" Seisensui's school falls under the latter. -

Volume XVIII CONTENTS 2010 Outcastes and Medical

Volume XVIII CONTENTS 2010 編纂者から From the Editors' Desk 1 Call for Papers; EMJNet at the AAS 2011 (with abstracts of presentations); This issue Articles 論文 On Death and Dying in Tokugawa Japan Outcastes and Medical Practices in Tokugawa Japan 5 Timothy Amos Unhappiness in Retirement: “Isho” of Suzuki Bokushi (1770-1842), a Rural Elite 26 Commoner Takeshi Moriyama The Death of Kobayashi Yagobei 41 Scot Hislop Embracing Death: Pure will in Hagakure 57 Olivier Ansart Executing Duty: Ōno Domain and the Employment of Hinin in the Bakumatsu Period 76 Maren Ehlers In Appreciation of Buffoonery, Egotism, and the Shōmon School: Koikawa Harumachi’s Kachō 88 kakurenbō (1776) W. Puck Brecher The Politics of Poetics: Socioeconomic Tensions in Kyoto Waka Salons and Matsunaga 103 Teitoku’s Critique of Kinoshita Chōshōshi Scott Alexander Lineberger The History and Performance Aesthetics of Early Modern Chaban Kyōgen 126 Dylan McGee Book Reviews 書評 Nam-lin Hur. Death and Social Order in Tokugawa Japan: Buddhism, Anti-Christianity, and 136 the Danka System Michael Laver Jonathan E. Zwicker. Practices of the Sentimental Imagination: Melodrama, the Novel, and 137 the Social Imaginary in Nineteenth-Century Japan J. Scott Miller William E. Clarke and Wendy E. Cobcroft. Tandai Shōshin Roku Dylan McGee 140 Basic Style Guidelines for Final Manuscript Submissions to EMJ 143 Editor Philip C. Brown Ohio State University Book Review Editor Glynne Walley University of Oregon Editorial Board Cheryl Crowley Emory University Gregory Smits Pennsylvania State University Patricia Graham Independent Scholar The editors welcome preliminary inquiries about manuscripts for publication in Early Modern Japan. Please send queries to Philip Brown, Early Modern Japan, Department of History, 230 West seventeenth Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210 USA or, via e-mail to [email protected]. -

NEW RISING HAIKU: the Evolution of Modern Japanese Haiku and the Haiku Persecution Incident by Itô Yûki

NEW RISING HAIKU: The Evolution of Modern Japanese Haiku and the Haiku Persecution Incident by Itô Yûki ABSTRACT The following discussion focuses on the evolution of the “New Rising Haiku” movement (shinkô haiku undô), examining events as they unfolded throughout the extensive wartime period, an era of recent history important to an understanding of the evolution of the “modern haiku movement,” that is, gendai haiku in Japan. In his 1985 book, My Postwar Haiku History, the acclaimed leader of the postwar haiku movement Kaneko Tohta (1919–) wrote, “When discussing the history of postwar haiku, many scholars tend to begin their discussion from the end of World War II. However, this perspective represents a rather stereotypical viewpoint. It is preferable that a discussion of postwar haiku history start from the midst of the war, or from the beginning of the ‘Fifteen Years War [1931-45].’” A discussion of the situation of haiku during Japan’s extended wartime era is of great historical significance, even if comparatively few are now aware of this history. In fact, the wartime era was a dark age for haiku; nonetheless it was through the ensuing persecutions and bitterness that gendai haiku evolved—an evolution which continues today. Please note that the two predominant schools or ‘approaches’ to contemporary Japanese haiku are: 1) gendai haiku (literally: “modern haiku”), and 2) traditional (dentô) haiku, a stylism signally represented by the Hototogisu circle and its journal of the same name. To avoid confusion, the term “modern haiku” (in English) will indicate contemporary (1920s-on) haiku in general, while “gendai haiku” refers to the progressive movement, its ideas and activities. -

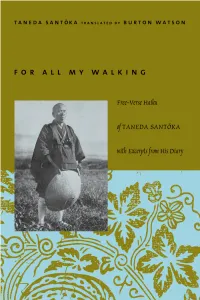

For All My Walking

Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page i for all my walking Modern Asian Literature Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page ii for all my walking Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page iii Translated by Burton Watson Free-Verse Haiku of Taneda Santoka with Excerpts from His Diaries columbia university press new york Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page iv Columbia University Press Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 2003 Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taneda, Santoka, 1882–1940. [Poems. English. Selections] For all my walking : free-verse haiku of Taneda Santoka with excerpts from his diaries / translated by Burton Watson. p. cm.—(Modern Asian literature series) ISBN 0–231–12516–X (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0–231–12517–8 (paper : alk. paper) I. Watson, Burton, 1925– II. Taneda, Santoka, 1882–1940. Nikki. English. Selections. III. Title. IV. Series. Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page v Contents Chronology of the Life of Taneda Santoka vii Introduction 1 Poems and Diary Entries 19 Bibliography of Works in English 103 Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page vi Watson(santoka)_FM 9/3/03 3:03 PM Page vii Chronology of the Life of Taneda Santo¯ka 1882 december 3. -

Haiku Od Revoluce Meidţi (1868) Do Současnosti

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI Filozofická fakutla Katedra bohemistiky – Katedra asijských studií Proměny ţánrů tanka a haiku od revoluce Meidţi (1868) do současnosti Transformations of the Tanka and Haiku Poetic Forms from the Meiji Restoration (1868) to the Present Day Disertační práce Autorka: Mgr. Sylva Martinásková Vedoucí práce: Prof. Zdenka Švarcová, Dr. Olomouc 2014 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem tuto disertační práci vypracovala samostatně pod vedením své školitelky a uvedla veškeré pouţité prameny a literaturu. V Olomouci …………………… Podpis ……………………………. Velice děkuji své školitelce prof. Zdence Švarcové, Dr., za odborné vedení, cenné rady a podněty, jakoţto i za trpělivost a čas, který mi věnovala. Ediční poznámka V práci je pouţita česká transkripce japonských pojmů a jmen s výjimkou bibliografických údajů anglicky psaných zdrojů, v nichţ je z důvodu snadnějšího dohledání ponechána anglická transkripce. Japonské výrazy (s výjimkou vlastních jmen) jsou v textu zvýrazněny kurzívou (např. tanka). Běţně známé japonské výrazy a geografická označení ponechávám bez kurzívy (např. sakura, Jasukuni). U těch japonských výrazů, které jiţ v českém jazykovém prostředí zdomácněly, je v textu ponechána tato zauţívaná česká podoba slova (např. Tokio). Kurzíva je dále pouţita pro fonetický přepis japonské verze básní. Japonské znaky jsou uvedeny u pojmů, názvů literárních děl a japonských vlastních jmen (s výjimkou názvů historických období a geografických označení). Japonská vlastní jména osob jsou uváděna v tradičním japonském pořadí, tzn. po příjmení/rodovém jméně následuje jméno osobní. Ţenská příjmení, která v originální podobě nenesou přechýlení, v textu zůstávají v nepřechýleném tvaru (např. Josano namísto podoby „Josan(o)ová“, Beichman namísto „Beichmanová“). U vlastních jmen obsahujících partikuli „no“ je skloňováno pouze druhé (tedy osobní) jméno (např. -

Otata 34 (October 2018)

otata 34 October, 2018 otata 34 October, 2018 otata 34 (October, 2018) Copyright ©2018 by the contributors. Translations by the contributors, except where otherwise noted. Cover photo by Jeannie Martin copyright © 2018 https://otatablog.wordpress.com [email protected] Contents tokonoma — Jean Giono Stefano d’Andrea 5 Alessandra Delle Fratte 67 Robert Christian 8 Corrado Aiello 69 Loren Goodman 10 Angela Giordano 70 Giuliana Ravaglia 17 Claudia Messelodi 73 Peter Yovu 25 Elisa Bernardinis 74 John Levy 28 Lucia Cardillo 76 David Gross 32 Angiola Inglese 78 Joseph Salvatore Aversano 34 Margherita Petriccione 80 Mark Young 36 Peter Newton 83 Tom Montag 40 Mark Levy 85 Richard Gilbert 43 Minh-Triêt Pham 86 Alegria Imperial 46 Madhuri Pillai 87 Kelly Sauvage Angel 48 Sonam Chhoki 88 Donna Fleischer 49 Guliz Mutlu 91 Bill Cooper 53 Damir Damir 93 Elmedin Kadric 55 Antonio Mangiameli 94 Patrick Sweeney 58 Eufemia Griffo 95 Louise Hopewell 63 Christina Sng 98 Lucy Whitehead 65 Jack Galmitz 99 Jeannie Martin 100 Supplement Clayton Beach The Pig and the Boar, or: The Limits to Brevity and Simplicity in Haiku 105 Richard Gilbert Pig & Boar, in the Haiku Wild: An Appreciation 131 from otata’s bookshelf Loren Goodman, Non-Existent Facts Tokonoma “There are truths you can sense,” he said, “and there are truths which I know. And what I know is greater. In summer, I go and hunt the Lady of the Moons in sand- pits. The sand is motionless, but the air above is restless. Then the sand begins to move, and the females come out. -

Akira Togawa Papers, 1921-1980

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf309nb20p No online items Finding Aid for the Akira Togawa Papers, 1921-1980 Processed by Yuji Ichioka and Makato Arakaki; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Note Area, Interdisciplinary, and Ethnic Studies--Asian American StudiesHistory--United States and North American HistoryArts and Humanities--Literature--Literature General Finding Aid for the Akira Togawa 1711 1 Papers, 1921-1980 Finding Aid for the Akira Togawa Papers, 1921-1980 Collection number: 1711 UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Manuscripts Division Los Angeles, CA Contact Information Manuscripts Division UCLA Library, Department of Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Telephone: 310/825-4988 (10:00 a.m. - 4:45 p.m., Pacific Time) Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ Processed by: Yuji Ichioka and Makoto Arakaki, 1993 Encoded by: Caroline Cubé Text converted and initial container list EAD tagging by: Apex Data Services Online finding aid edited by: Amy Shung-Gee Wong, March 2001 Funding: This online finding aid has been funded in part by a grant from the Library Services and Technology Act (LSTA). © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Akira Togawa Papers, Date (inclusive): 1921-1980 Collection number: 1711 Creator: Togawa, Akira, 1903- Extent: 55 boxes (27.5 linear ft.)3 oversize boxes Repository: University of California, Los Angeles.