For All My Walking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

Boonshoft Museum of Discovery • Dayton, OH

THIS IS THE HOUSE ROCK BUILT We’re not your typical creative agency. We’re an idea collective. A house of thought and execution. We’re a grab bag of innovators, illustrators, designers and rockstars who are always in pursuit of the big idea! Our building, which was one of the last record stores in America, serves as a playground for our creative minds to frolic and thrive. This is not a design firm. It’s something new and forward-thinking. It’s about going beyond design and messaging. It’s about forging game-changing ideas and harvesting epic results. It’s about YOU. Welcome to U! Creative. U! Creative, Inc Key Contact: (dba: Destination2, The Social Farm) Ron Campbell - President 72 S. Main St. Miamisburg, OH 45342 P: 937.247.2999 Ext. 103 | C: 937.271.2846 P: 937.247.2999 | www.ucreate.us [email protected] UCreative U_Creative in/roncampbell7 U_Creative UCreativeTV That’s because our focus at U! goes beyond providing out-of-the-box thinking. Beyond strategic planning. Beyond creating hard-hitting messaging, engaging design or captivating imagery. Even beyond moving the needle. WE’RE NOT YOUR First and foremost, U! is about building relationships. It’s about unity. It’s about strong ideas and ideals converging. It’s about staying focused on the point of view, needs and desires of others. Because when you get that right, all the rest naturally follows. TYPICAL AGENCY Turn the page and see for yourself. © 2019 U! Creative, Inc. THEthe company COMPANY U! keep U! KEEP © 2019 U! Creative, Inc. -

Exploiting Prior Knowledge During Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio

Exploitatie van voorkennis bij het automatisch afleiden van toonaarden en akkoorden uit muzikale audio Exploiting Prior Knowledge during Automatic Key and Chord Estimation from Musical Audio Johan Pauwels Promotoren: prof. dr. ir. J.-P. Martens, prof. dr. M. Leman Proefschrift ingediend tot het behalen van de graad van Doctor in de Ingenieurswetenschappen Vakgroep Elektronica en Informatiesystemen Voorzitter: prof. dr. ir. R. Van de Walle Faculteit Ingenieurswetenschappen en Architectuur Academiejaar 2015 - 2016 ISBN 978-90-8578-883-6 NUR 962, 965 Wettelijk depot: D/2016/10.500/15 Abstract Chords and keys are two ways of describing music. They are exemplary of a general class of symbolic notations that musicians use to exchange in- formation about a music piece. This information can range from simple tempo indications such as “allegro” to precise instructions for a performer of the music. Concretely, both keys and chords are timed labels that de- scribe the harmony during certain time intervals, where harmony refers to the way music notes sound together. Chords describe the local harmony, whereas keys offer a more global overview and consequently cover a se- quence of multiple chords. Common to all music notations is that certain characteristics of the mu- sic are described while others are ignored. The adopted level of detail de- pends on the purpose of the intended information exchange. A simple de- scription such as “menuet”, for example, only serves to roughly describe the character of a music piece. Sheet music on the other hand contains precise information about the pitch, discretised information pertaining to timing and limited information about the timbre. -

K-5Th) Girls K-5 Chapel to Be Worn on Wednesdays and Some Field Trips Jumper – Hunter/Classic Navy Plaid (Must Be Purchased from Lands’ End) NO SKIRTS

THE OAK HALL EPISCOPAL SCHOOL 2021/2022 UNIFORM CODE Uniforms will be worn everyday except Friday. There will be other times during the year when students may earn free days. LOWER SCHOOL (K-5th) Girls K-5 Chapel To be worn on Wednesdays and some field trips Jumper – Hunter/Classic Navy Plaid (must be purchased from Lands’ End) NO SKIRTS. White knit blouse with Peter Pan collar (long or short sleeve) Black modesty shorts (for under jumper) Solid white anklet or knee socks (no logos) and navy leggings or tights (if needed due to temperature) Mary Jane or Saddle shoes in white and navy or black (skid resistant soles) M, T, Tr Khaki shorts, pants, capri pants, A-line skirt or skort, NO JEGGINGS (shorts, skirts and skorts must be no shorter than a dollar bill’s width from the mid knee) *1st–5th GRADE - SHORTS & PANTS MUST HAVE BELT LOOPS! Solid color polo shirt in white, navy or red (long or short sleeve) Solid white anklet or crew socks, solid white knee socks or opaque white, navy or black tights or leggings. Lands’ End Mocs, Mary Janes or loafer shoes in black, navy, marine blue, tan or mahogany. Simple athletic shoes (no characters, lights, etc.) are also allowed. No clogs, boots, flip flops or sandals are permitted. Plain brown or black belts are required with pants, shorts, skorts and skirts that have belt loops (except Kindergarten) SHORTS MUST BE WORN UNDER DRESSES AND SKIRTS Boys K-5 Chapel To be worn on Wednesdays and some field trips Khaki pants or shorts (NO CARGOS) - *1st–5th GRADE - SHORTS & PANTS MUST HAVE BELT LOOPS! Blue -

Japanese Hermeneutics

JAPANESE HERMENEUTICS CURRENT DEBATES ON AESTHETICS AND INTERPRETATION EDITED BY MICHAEL F. MARRA JAPANESE HERMENEUTICS JAPANESE HERMENEUTICS CURRENT DEBATES ON AESTHETICS AND INTERPRETATION EDITED BY MICHAEL F. MARRA University of Hawai‘i Press Honolulu © 2002 University of Hawai‘i Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 07 06 05 04 03 02 654321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Japanese hermeneutics : current debates on aesthetics and interpretation / edited by Michael F. Marra. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-8248-2457-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Aesthetics, Japanese. 2. Hermeneutics. 3. Japanese literature— History and criticism. I. Marra, Michele. BH221.J3 J374 2000 111Ј.85Ј0952—dc21 2001040663 University of Hawai‘i Press books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Council on Library Resources. Designed by Carol Colbath Printed by The Maple-Vail Book Manufacturing Group Volano gli angeli in Paradiso Che adornano con il sorriso Nel ricordo di Gemmina (1960 –2000) CONTENTS Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction Michael F. Marra 1 HERMENEUTICS AND JAPAN 1. Method, Hermeneutics, Truth Gianni Vattimo 9 2. Poetics of Intransitivity Sasaki Ken’ichi 17 3. The Hermeneutic Approach to Japanese Modernity: “Art-Way,” “Iki,” and “Cut-Continuance” O¯ hashi Ryo¯suke 25 4. Frame and Link: A Philosophy of Japanese Composition Amagasaki Akira 36 5. The Eloquent Stillness of Stone: Rock in the Dry Landscape Garden Graham Parkes 44 6. Motoori Norinaga’s Hermeneutic of Mono no Aware: The Link between Ideal and Tradition Mark Meli 60 7. Between Individual and Communal, Subject and Object, Self and Other: Mediating Watsuji Tetsuro¯’s Hermeneutics John C. -

Soseki's Botchan Dango ' Label Tamanoyu Kaminoyu Yojyoyu , The

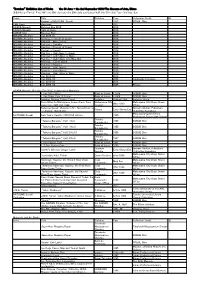

"Botchan" Exhibition List of Works the 30 June - the 2nd September 2018/The Museum of Arts, Ehime ※Exhibition Period First Half: the 30th Jun sat.-the 29th July sun/Latter Half: the 31th July Tue.- 2nd Sep. Sun Artist Title Piblisher Year Collection Credit ※ Portrait of NATSUME Soseki 1912 SOBUE Shin UME Kayo Botchans' 2017 ASADA Masashi Botchan Eye 2018' 2018 ASADA Masashi Cats at Dogo 2018 SOBUE Shin Botchan Bon' 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2018-01 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - White Heron 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Camellia 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Portrait of Soseki 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi-Neko in Green 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko at Night 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko with Blue Sky 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Turner Island 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Pegasus 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 1 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Drawing - Sabi -Neko 2 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Painting - Sabi -Neko in White 2018 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2013-03 2013 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2002-02 2002 Takahashi Collection MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2014-02 2014 MISAWA Atsuhiko Cat 2006-04 2006 Private ASADA Masashi 'Botchan Eye 2018' Collaboration Materials 1 Yen Bill (2 Bills) Bank of Japan c.1916 SOBUE Shin 1 Yen Silver Coin (3 Coins) Bank of Japan c.1906 SOBUE Shin Iyotetsu Railway Ticket (Copy) Iyotetsu Original:1899 Iyotetsu Group From Mitsu to Matsuyama, Lower Class, Fare Matsuyama City Matsuyama City Dogo Onsen after 1950 3sen 5rin , 28th Oct.,1888 Tourism Office Natsume Soseki, Botchan 's Inn Yamashiroya is Iwanami Shoten, Publishers. -

Hoshi Pharmaceuticals in the Interwar Years Timothy M. Yang Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Th

Market, Medicine, and Empire: Hoshi Pharmaceuticals in the Interwar Years Timothy M. Yang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Timothy M. Yang All rights reserved ABSTRACT Market, Medicine, and Empire: Hoshi Pharmaceuticals in the Interwar Years Timothy M. Yang This dissertation examines the connections between global capitalism, modern medicine, and empire through a close study of Hoshi Pharmaceuticals during the interwar years. As one of the leading drug companies in East Asia at the time, Hoshi embodied Japan's imperial aspirations, rapid industrial development, and burgeoning consumer culture. The company attempted to control every part of its supply and distribution chain: it managed plantations in the mountains of Taiwan and Peru for growing coca and cinchona (the raw material for quinine) and contracted Turkish poppy farmers to supply raw opium for government-owned refineries in Taiwan. Hoshi also helped shape modern consumer culture in Japan and its colonies, and indeed, became an emblem for it. At its peak in the early 1920s, Hoshi had a network of chain stores across Asia that sold Hoshi-brand patent medicines, hygiene products, and household goods. In 1925, however, the company's fortunes turned for the worse when an opium trading violation raised suspicions of Hoshi as a front for the smuggling of narcotics through Manchuria and China. Although the company was a key supplier of medicines to Japan's military during World War Two, it could not financially recover from the fallout of the opium scandal. -

Women's Hosiery

STUDIO N - FOR INTERNAL AND VENDOR USE ONLY ONLINE PHOTOGRAPHY GUIDE - Womens_Hosiery 1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 2. Hosiery Leggings 3. Sheer, Textured & Thigh high Hosiery 4. Shaper Hosiery 5. Sweater Tights 6. Over the Knee Socks, Leg Warmers & Trendy Thigh Highs - onfig 7. Socks: Knee-hi / no-show / ankle / -onfig 8. Socks: Womens sock sets / boot liners –product 9. Socks: Nike Elite 1 STUDIO N - FOR INTERNAL AND VENDOR USE ONLY ONLINE PHOTOGRAPHY GUIDE - Womens_Hosiery Hosiery Leggings MAIN AND ALT PRESENTATION Front Lower Front view, crop above waist/ belly button. Styling to cover top of waistband. Back Lower Back view, crop above waist. Style with cami to show waistband and possible pocket detail. Side Lower Side view. Crop above waist. NO HANDS Style with cami to show waistband and possible pocket detail. Left or right depending on the details. Detail Lower Detail view as shown unless there is a better detail determined on set. Zoom Lower Zoom detail - for closeup of fabric, textures and prints. Avoid seams, wrinkles and graphics on tees. (Vendor images exempt) Front Full (look) Gold Look / Editorial / Catalog / video, if available ADDITIONAL INFO swatch presentation Styling Exception: Multipurpose Hosiery Legging styled bare feet and bare top when requested. 2 STUDIO N - FOR INTERNAL AND VENDOR USE ONLY ONLINE PHOTOGRAPHY GUIDE - Womens_Hosiery Sheer, Textured, Control Top & Thigh High Hosiery MAIN AND ALT PRESENTATION Side Full Side view with right leg forward (watch distance between feet) NO HANDS Crop above top of hosiery. Detail Full (optional) Detail view if requested or needed. Front, Back or closeup on detail. -

Kigo-Articles.Pdf

Kigo Articles Contained in the All-in-One PDF 1) Kigo and Seasonal Reference: Cross-cultural Issues in Anglo- American Haiku Author: Richard Gilbert (10 pages, 7500 words). A discussion of differences between season words as used in English-language haiku, and kigo within the Japanese literary context. Publication: Kumamoto Studies in English Language and Literature 49, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan, March 2006 (pp. 29- 46); revised from Simply Haiku 3.3 (Autumn 2005). 2) A New Haiku Era: Non-season kigo in the Gendai Haiku saijiki Authors: Richard Gilbert, Yûki Itô, Tomoko Murase, Ayaka Nishikawa, and Tomoko Takaki (4 pages, 1900 words). Introduction to the Muki Saijiki focusing on the muki kigo volume of the 2004 the Modern Haiku Association (Gendai Haiku Kyôkai; MHA). This article contains the translation of the Introduction to the volume, by Tohta Kaneko. Publication: Modern Haiku 37.2 (Summer 2006) 3) The Heart in Season: Sampling the Gendai Haiku Non-season Muki Saijiki – Preface Authors: Yûki Itô, with Richard Gilbert (3 pages, 1400 words). An online compliment to the Introduction by Tohta Kaneko found in the above-referenced Muki Saijiki article. Within, some useful information concerning the treatments of kigo in Bashô and Issa. Much of the information has been translated from Tohta Kaneko's Introduction to Haiku. Publication: Simply Haiku Journal 4.3 (Autumn 2006) 4) The Gendai Haiku Muki Saijiki -- Table of Contents Authors: Richard Gilbert, Yûki Itô, Tomoko Murase, Ayaka Nishikawa, and Tomoko Takaki (30 pages, 9300 words). A bilingual compilation of the keywords used in the Muki Saijiki Table of Contents. -

166-90-06 Tel: +38(063)804-46-48 E-Mail: [email protected] Icq: 550-846-545 Skype: Doowopteenagedreams Viber: +38(063)804-46-48 Web

tel: +38(097)725-56-34 tel: +38(099)166-90-06 tel: +38(063)804-46-48 e-mail: [email protected] icq: 550-846-545 skype: doowopteenagedreams viber: +38(063)804-46-48 web: http://jdream.dp.ua CAT ORDER PRICE ITEM CNF ARTIST ALBUM LABEL REL G-049 $60,37 1 CD 19 Complete Best Ao&haru (jpn) CD 09/24/2008 G-049 $57,02 1 SHMCD 801 Latino: Limited (jmlp) (ltd) (shm) (jpn) CD 10/02/2015 G-049 $55,33 1 CD 1975 1975 (jpn) CD 01/28/2014 G-049 $153,23 1 SHMCD 100 Best Complete Tracks / Various (jpn)100 Best... Complete Tracks / Various (jpn) (shm) CD 07/08/2014 G-049 $48,93 1 CD 100 New Best Children's Classics 100 New Best Children's Classics AUDIO CD 07/15/2014 G-049 $40,85 1 SHMCD 10cc Deceptive Bends (shm) (jpn) CD 02/26/2013 G-049 $70,28 1 SHMCD 10cc Original Soundtrack (jpn) (ltd) (jmlp) (shm) CD 11/05/2013 G-049 $55,33 1 CD 10-feet Vandalize (jpn) CD 03/04/2008 G-049 $111,15 1 DVD 10th Anniversary-fantasia-in Tokyo Dome10th Anniversary-fantasia-in/... Tokyo Dome / (jpn) [US-Version,DVD Regio 1/A] 05/24/2011 G-049 $37,04 1 CD 12 Cellists Of The Berliner PhilharmonikerSouth American Getaway (jpn) CD 07/08/2014 G-049 $51,22 1 CD 14 Karat Soul Take Me Back (jpn) CD 08/21/2006 G-049 $66,17 1 CD 175r 7 (jpn) CD 02/22/2006 G-049 $68,61 2 CD/DVD 175r Bremen (bonus Dvd) (jpn) CD 04/25/2007 G-049 $66,17 1 CD 175r Bremen (jpn) CD 04/25/2007 G-049 $48,32 1 CD 175r Melody (jpn) CD 09/01/2004 G-049 $45,27 1 CD 175r Omae Ha Sugee (jpn) CD 04/15/2008 G-049 $66,92 1 CD 175r Thank You For The Music (jpn) CD 10/10/2007 G-049 $48,62 1 CD 1966 Quartet Help: Beatles Classics (jpn) CD 06/18/2013 G-049 $46,95 1 CD 20 Feet From Stardom / O. -

09062299296 Omnislashv5

09062299296 omnislashv5 1,800php all in DVDs 1,000php HD to HD 500php 100 titles PSP GAMES Title Region Size (MB) 1 Ace Combat X: Skies of Deception USA 1121 2 Aces of War EUR 488 3 Activision Hits Remixed USA 278 4 Aedis Eclipse Generation of Chaos USA 622 5 After Burner Black Falcon USA 427 6 Alien Syndrome USA 453 7 Ape Academy 2 EUR 1032 8 Ape Escape Academy USA 389 9 Ape Escape on the Loose USA 749 10 Armored Core: Formula Front – Extreme Battle USA 815 11 Arthur and the Minimoys EUR 1796 12 Asphalt Urban GT2 EUR 884 13 Asterix And Obelix XXL 2 EUR 1112 14 Astonishia Story USA 116 15 ATV Offroad Fury USA 882 16 ATV Offroad Fury Pro USA 550 17 Avatar The Last Airbender USA 135 18 Battlezone USA 906 19 B-Boy EUR 1776 20 Bigs, The USA 499 21 Blade Dancer Lineage of Light USA 389 22 Bleach: Heat the Soul JAP 301 23 Bleach: Heat the Soul 2 JAP 651 24 Bleach: Heat the Soul 3 JAP 799 25 Bleach: Heat the Soul 4 JAP 825 26 Bliss Island USA 193 27 Blitz Overtime USA 1379 28 Bomberman USA 110 29 Bomberman: Panic Bomber JAP 61 30 Bounty Hounds USA 1147 31 Brave Story: New Traveler USA 193 32 Breath of Fire III EUR 403 33 Brooktown High USA 1292 34 Brothers in Arms D-Day USA 1455 35 Brunswick Bowling USA 120 36 Bubble Bobble Evolution USA 625 37 Burnout Dominator USA 691 38 Burnout Legends USA 489 39 Bust a Move DeLuxe USA 70 40 Cabela's African Safari USA 905 41 Cabela's Dangerous Hunts USA 426 42 Call of Duty Roads to Victory USA 641 43 Capcom Classics Collection Remixed USA 572 44 Capcom Classics Collection Reloaded USA 633 45 Capcom Puzzle -

Gaining and Maintaining Brand Loyalty Through the Lens of K-Pop

Just Right: Gaining and Maintaining Brand Loyalty Through the Lens of K-Pop by Panisa Sermchaiwong Thesis Advisor: Anocha Aribarg A senior thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the Michigan Ross Senior Thesis Seminar (BA 480), (4/22/2021). Abstract Understanding how to build, maintain, and utilize brand loyalty is essential in today’s business world. Given increasing competition for a customer’s limited attention span, learning how to foster brand loyalty among customers gives a business considerable competitive advantage. This research will examine the impact of firm-level marketing techniques employed by the Korean music industry on consumer brand loyalty. In-depth interviews of K-Pop consumers were conducted in tandem with an online survey amongst a pool of randomly selected, consistent K-Pop consumers to gauge the effects of 1) gamification marketing techniques and 2) exclusive ecosystem marketing techniques on building consumer brand loyalty. The effects will be analyzed using: 1) a thematic analysis of the interview transcripts, and 2) a mediated correlational analysis with firm-level tactics of gamification and exclusive ecosystem as the independent variables, brand loyalty as the dependent variable, and brand community as the mediator variable. Findings from this research will determine whether marketing tactics employed by players in the Korean music industry are effective on customers, and if so, provide incentive for other businesses to pursue similar tactics to build loyalty for their own brands. Contents