Shugendo and Its Lore Most of What We Know of Shugendo Belongs to the Realm of Danshd Ej$ , That Is, "Tradition" Or Miscellaneous Lore

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Omori Sogen the Art of a Zen Master

Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Omori Roshi and the ogane (large temple bell) at Daihonzan Chozen-ji, Honolulu, 1982. Omori Sogen The Art of a Zen Master Hosokawa Dogen First published in 1999 by Kegan Paul International This edition first published in 2011 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © The Institute of Zen Studies 1999 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0–7103–0588–5 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978–0–7103–0588–6 (hbk) Publisher’s Note The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace. Dedicated to my parents Contents Acknowledgements Introduction Part I - The Life of Omori Sogen Chapter 1 Shugyo: 1904–1934 Chapter 2 Renma: 1934–1945 Chapter 3 Gogo no Shugyo: 1945–1994 Part II - The Three Ways Chapter 4 Zen and Budo Chapter 5 Practical Zen Chapter 6 Teisho: The World of the Absolute Present Chapter 7 Zen and the Fine Arts Appendices Books by Omori Sogen Endnotes Index Acknowledgments Many people helped me to write this book, and I would like to thank them all. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Art of Zen Buddhism Zen Buddhism, Which Stresses a Connection to The

Art of Zen Buddhism Zen Buddhism, which stresses a connection to the spiritual rather than the physical, was very influential in the art of Kamakura Japan. Zen Calligraphy of the Kamakura Period Calligraphy by Musō Soseki (1275–1351, Japanese zen master, poet, and calligrapher. The characters "別無工夫 " ("no spiritual meaning") are written in a flowing, connected soshō style. A deepening pessimism resulting from the civil wars of 12th century Japan increased the appeal of the search for salvation. As a result Buddhism, including its Zen school, grew in popularity. Zen was not introduced as a separate school of Buddhism in Japan until the 12th century. The Kamakura period is widely regarded as a renaissance era in Japanese sculpture, spearheaded by the sculptors of the Buddhist Kei school. The Kamakura period witnessed the production of e- maki or painted hand scrolls, usually encompassing religious, historical, or illustrated novels, accomplished in the style of the earlier Heian period. Japanese calligraphy was influenced by, and influenced, Zen thought. Ji Branch of Pure Land Buddhism stressing the importance of reciting the name of Amida, nembutsu (念仏). Rinzai A school of Zen buddhism in Japan, based on sudden enlightenment though koans and for that reason also known as the "sudden school". Nichiren Sect Based on the Lotus Sutra, which teaches that all people have an innate Buddha nature and are therefore inherently capable of attaining enlightenment in their current form and present lifetime. Source URL: https://www.boundless.com/art-history/japan-before-1333/kamakura-period/art-zen-buddhism/ Saylor URL: http://www.saylor.org/courses/arth406#4.3.1 Attributed to: Boundless www.saylor.org Page 1 of 2 Nio guardian, Todai-ji complex, Nara Agyō, one of the two Buddhist Niō guardians at the Nandai-mon in front of the Todai ji in Nara. -

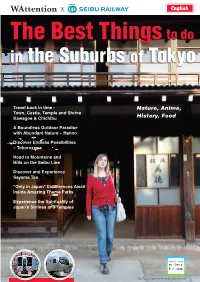

In the Suburbs of Tokyo

English The Best Things to do in the Suburbs of Tokyo Travel back in time - Nature, Anime, Town, Castle, Temple and Shrine Kawagoe & Chichibu History, Food A Boundless Outdoor Paradise with Abundant Nature -- Hanno Discover Endless Possibilities -- Tokorozawa Head to Mountains and Hills on the Seibu Line Discover and Experience Sayama Tea "Only in Japan" Experiences Await Inside Amazing Theme Parks Experience the Spirituality of Japan’s Shrines and Temples Edo-Tokyo Open Air Architectural Museum SEIBU_EN_2020.indd 1 2020/12/03 11:07 Get around the Seibu Line with the All-you-can-ride Pass With the SEIBU 1Day Pass and other discount tickets, issued by Seibu Railway, you can hop on and off the SEIBU Line as often as you want to experience rich Japanese culture and visit sightseeing gems hidden in the suburbs. The Seibu Lines connect directly to the sacred and traditional places of Kawagoe and Chichibu, where you can enjoy the charm of the Edo period to the fullest. These tickets are the best partner for foreign tourists visiting Japan! Ticket Information Price and Type MOOMINVALLEY PARK Ticket & Travel Pass 3,700 yen SEIBU SEIBU * Only valid for the boarding date. Includes a SEIBU 1Day Pass, 1Day Pass 1Day Pass + Nagatoro ZKLFKDOORZVXQOLPLWHGULGHVRQDOO6(Ζ%85DLOZD\OLQHV H[FHSW 1,000 yen 1,500 yen IRUWKH7DPDJDZD/LQH DEXVWLFNHWWRPHWV¦IURP+DQQď 6WDWLRQRU+LJDVKL+DQQď6WDWLRQDQGDSDUNDGPLVVLRQWLFNHW * Some attractions in the park are charged separately. * SEIBU 2Day Pass and SEIBU 2Day Pass + Nagatoro tickets are also available. * Tickets are only valid on the day of use. Valid on the SEIBU KAWAGOE PASS Seibu Line or the Seibu Line + Chichibu Railway Line 700 yen within the stated area including free use between 1RJDPL6WDWLRQDQG0LWVXPLQHJXFKL6WDWLRQb 7LFNHWV * Tickets are valid for only one day of use for are not valid for the Tamagawa Line) arrival or departure from Seibu-Shinjuku Station, * Additional limited express charge is required. -

Lake Biwa Comprehensive Preservation Initiatives

Bequeathing a Clean Lake Biwa to Future Generations Lake Biwa Comprehensive Preservation Initiatives ― Seeking Harmonious Coexistence with the Lake's Ecosystem ― Lake Biwa Comprehensive Preservation Liaison Coordination Council Lake Biwa Comprehensive Preservation Promotion Council Contents 1 Overview of Lake Biwa and the Yodo River Basin ○ Overview of the Yodo River Basin 1 ○ Water Use in Lake Biwa and the Yodo River Basin ○ Land Use in Lake Biwa and the Yodo River Basin 2 Overview of Lake Biwa ○ Lake Biwa, an Ancient Lake 2 ○ Dimensions of Lake Biwa 3 Development of Lake Biwa and the Yodo River Basin ○ Early History 3 ○ Expanded Farmlands, Increased Rice Production and Subsequent Development of Commerce ○ A Political Center and Cradle of Culture and Tradition ○ Industrial and Economic Development after the Meiji Restoration ○ Changing Lifestyles 4 Background of Lake Biwa Comprehensive ○ Farmland Development and Flooding in the Edo Period (1603 - 1868) 5 Development Program ○ Flood Control During the Meiji Period (1868 - 1912) ○ Modern Projects for Using Water of Lake Biwa ○ Increasing Demand for Water in the Showa Period (1926 - 1989) 5 Lake Biwa Comprehensive Development Program ○ Program System 7 ○ Breakdown of the Program Expenses ○ Environmental Preservation ○ Flood Control ○ Promotion Effective Water Use 6 Outcomes of the Lake Biwa ○ Effects of Flood Control Projects 9 Comprehensive Development Program ○ Effects of Projects Promoting Effective Use of Water ○ Effects of Environmental Preservation Projects 7 Current Situation of -

Kyushu with Hiroko, November 11 - 22, 2018 Trip Overview

Kyushu with Hiroko, November 11 - 22, 2018 Trip Overview Kyushu, the southernmost large island of Japan, is chockfull of incredible interests of so many kinds. I have visited Kyushu in past years on business. During such trips I didn’t experience what visitors do in Kyushu, so I had no idea of the huge variety of amazing sights and experiences Kyushu can offer to us. Last year I decided to make Kyushu is the next destination for my annual tour to Japan. Thus was born the initial idea for Kyushu with Hiroko 2018. I have deeply studied the history, natural environment, onsen hot springs, geology, food, art and people of Kyushu. Then, I carefully picked the places, each of which highlights the unique characteristics of Kyushu. This past December, I made this circuit on my own to absolutely confirm my expectations for the tour. This tour plan is the result of my study and exploration: Kyushu with Hiroko 2018. Join me on this fascinating, educational, fun and delicious tour to Kyushu this November! Some of you may have heard these Japanese culinary words: kabocha (squash), kara-age (a deep-frying method without batter), tempura (deep-frying method with batter), chawan’mushi (savory egg custard), kasutera (pound cake) just to name a few. These words describe foods and cooking techniques brought from abroad to Kyushu, reflecting the rich history of foreign influence that extend back nearly 1500 years. This unique history of foreign influence is a major part of the fascination of Kyushu. It is very different from that experienced in the usual more familiar tourist precincts of Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto. -

Itinerary Is Subject to Availability

Quote Date: 16 June 2017 Quote Reference: 2000975 Consultant: Samantha Hall [email protected] The Garden Trust Japan Trip Spring 2018 Price details Passengers Price Per Person 12 £4,704 13 £4,521 14 £4,365 15 £4,231 Single Supplement: £ 672.00 per person (subject to room availability) The above price is inclusive of a full time InsideJapan Tour Guide for the duration of the tour All of the accommodation included within this itinerary is subject to availability. Where hotels are not available, accommodation of a similar price and location will be used. This quote is valid at the current price for 30 days, after this period we will be happy to provide you with a re- quote based on the situation at that time. A deposit of £300 per person will be required to secure a place on this trip. Get beneath the surface www.InsideJapanTours.com 1 Part of InsideAsia Tours Ltd, an award-winning travel company offering group tours, tailored travel and cultural experiences across Japan, Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos and Burma. Itinerary in brief Location Day to Day Detail Accommodation Day 1 Kyoto Shared Shuttle Bus from Kansai Airport to Kyoto Royal Park The Kyoto. Hotel Met at Hotel by full time IJT Local Tour Leader for 14 days. Day 2 Kyoto Private minibus for Miho Museum trip Royal Park The Kyoto. Miho Museum Celebratory Dinner Day 3 Nara Private minibus for Nara sightseeing Royal Park The Kyoto. Heijo Palace (To-in Teien and Imperial Villa Garden Archaeological Garden), Isuien Garden, Todaiji Temple, Nandaimon Gate and Nara Deer Park Lunch at local restaurant Day 4 Kyoto Private minibus for Kyoto sightseeing Royal Park The Kyoto. -

Online Addn Kanji Guide.Indd

1 AI; hira(ku), push open Radical: 扌 (3 + 7) 挨拶 aisatsu, a greeting, salutation Strokes: 10 挨拶回り Grade: 8 aisatsu mawari, courtesy calls 挨 JLPT level: Y-1 挨拶状 aisatsujō, greeting card JIS Code: 3027 2 AI; kurai, dark, not clear Radical: 日 (4+13) 曖昧 aimai, vague, obscure, ambiguous, suspicious Strokes: 17 曖昧さ Grade: 8 aimaisa, ambiguity 曖 JLPT level: JIS Code: 5B23 3 EN; a(teru), address 宀 Radical: (3+5) 宛名 Strokes: 8 atena, addressee, an address Grade: 8 宛先 atesaki, an address 宛 JLPT level: Y-1 宛がい扶持 ategaibuchi, discretionary allowance JIS Code: 3038 4 RAN; arashi, storm, tempest Radical: 山 (3+9) 夜嵐 yoarashi, evening storm Strokes: 12 青嵐 Grade: 8 aoarashi, storm in the verdant mountains 嵐 JLPT level: 1 嵐気 ranki, mountain mist, mountain air JIS Code: 4D72 5 I; oso(reru), fear; kashiko(mu), obey, humble oneself; kashiko(i), majestic Radical: 田 (5+4) Strokes: 9 Grade: 8 畏怖 ifu, fear, fright, awe 畏 JLPT level: 畏敬 ikei, reverence, awe JIS Code: 305A 畏友 iyū, respected friend 6 I; na(eru),weaken, wither, droop; shibo(mu), shio(reru), shina(biru), wither, fade Radical: 艹 (6+5) Strokes: 11 Grade: 8 萎縮 ishuku, wither, shrink, atrophy 萎 JLPT level: 萎靡 ibi, decline, decay, drooping JIS Code: 3060 7 I; chair Radical: 木 (4+8) 椅子 isu, chair Strokes: 12 車椅子 Grade: 8 kurumaisu, wheel chair 椅 JLPT level: Y-1 JIS Code: 3058 8 I; same kind Radical: 彑 (3+10) 語彙 goi, vocabulary Strokes: 13 彙類 Grade: 8 irui, category, classification 彙 JLPT Level: 彙報 ihō, collection of classified reports JIS Code: 5743 9 ibara, briar, thorn Radical: 艹 (3+6) 茨城県 Ibaraki ken Ibaraki -

Temple Treasures of Japan

5f?a®ieiHas3^ C-'Vs C3ts~^ O ft Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/ternpletreasureso00pier_0 Bronze Figure of Amida at Kamakura. Cast by Ono Goroyemon, 1252 A. D. Foundation-stones of Original Temple seen to left of Illustration. Photographed by the Author. TEMPLE TREASURES OF JAPAN BY GARRETT CHATFIELD PIER NEW YORK FREDERIC FAIRCHILD SHERMAN MCMXIV Copyright, 1914, by Frederic Fairchild Sherman ILLUSTRATIONS Bronze Figure of Amida at Kamakura. Cast by Ono Goroyemon, 1252 A. D. Foundation- stones of Original Temple seen to left of Illustration Frontispiece Facing Pig. Page 1. Kala, Goddess of Art. Dry lacquer. Tempyo Era, 728-749. Repaired during the Kamakura Epoch (13th Century). Akishinodera, Yamato .... 16 2. Niomon. Wood, painted. First Nara Epoch (711 A. D.). Horyuji, Nara 16 3. Kondo or Main Hall. First Nara Epoch (71 1 A. D.). Horyuji, Nara 16 4. Kwannon. Copper, gilt. Suiko Period (591 A. D.). Imperial Household Collection. Formerly Horyuji, Nara 16 5. Shaka Trinity. Bronze. Cast by Tori (623 A. D.) Kondo Horyuji 17 6. Yakushi. Bronze. Cast by Tori (607 A. D.). Kondo, Horyuji 17 7. Kwannon. Wood. Korean (?) Suiko Period, 593-628, or Earlier. Nara Museum, Formerly in the Kondo, Horyuji 17 8. Kwannon. Wood, Korean (?) Suiko Period, 593-628, or Earlier. Main Deity of the Yumedono, Horyuji . 17 9. Portable Shrine called Tamamushi or “Beetle’s Wing” Shrine. Wood painted. Suiko Period, 593- 628 A. D. Kondo, Horyuji 32 10. Kwannon. Wood. Attributed to Shotoku Taishi, Suiko Period, 593-628. Main Deity of the Nunnery of Chuguji. -

Human-Induced Traumas in the Skulls Excavated from Gokurakuji Site, Kamakura, Japan

Bull. Natl. Mus. Nat. Sci., Ser. D, 42, pp. 1–17, December 22, 2016 Human-induced traumas in the skulls excavated from Gokurakuji site, Kamakura, Japan Kazuhiro Sakaue Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Nature and Science, 4–1–1 Amakubo, Tsukuba-city, Ibaraki Prefecture 300-0005, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This study investigates the human-induced traumas in the skulls excavated from the Gokurakuji site macroscopically. Human-induced traumas were classified into four types, like gashes, incisions, scratches, and blunt force trauma. The results revealed that the number of skulls with gashes or incisions tended to be low (1 individual with a gash and 4 individuals with incisions out of 331 individuals) among those of previously reported populations in medieval and recent Japan. These results suggested that the skulls found on Gokurakuji site might be not have belonged to victims of the battle of Nitta Yoshisada in 1333. Additionally, the relatively high number of specimens with scratches (21 or 6.3%), also the second highest among the discussed sites, could have resulted from differences in diagnostic standards or differences in the purpose or method used for inducing scratches. Key words: Human-induced, trauma, Kamakura, Medieval, Skull th th 14 Introduction 12 to 13 centuries based on C aging of human skeletal remains from the Yuigahama Human-induced traumas in human skeletal Chusei Shudan Bochi and Yuigahama-minami materials have been examined as objective evi- sites (Minami et al., 2006). dence of interpersonal violence in the fields of According to Suzuki (1956)’s theory, the physical and forensic anthropology (Suzuki, sharp-edged traumas of the skulls excavated 1956; Boylston, 2000; Williamson et al., 2003; from the Yuigahama area are classified into three Nagaoka and Abe, 2007; Dodo et al., 2008; types: “gashes (penetrating both the external and Sakaue, 2010). -

ART a Legacy Spanning Two Millennia

For more detailed information on Japanese government policy and other such matters, see the following home pages. Ministry of Foreign Affairs Website http://www.mofa.go.jp/ Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ ART A legacy spanning two millennia Scroll painting A scene from the 12th-century Tale of Genji Scrolls (Genji monogatari emaki), which portray events from the 11th-century novel Tale of Genji. National Treasure. © Tokugawa Art Museum iverse factors have contributed to the the beginning of the era, manufactured copper Ddevelopment of Japanese art. Both weapons, bronze bells, and kiln-fired ceramics. technologically and aesthetically, it has for Typical artifacts from the Kofun (Tumulus) many centuries been influenced by Chinese period (approximately A.D. 300 to A.D. 710) styles and cultural developments, some of that followed, are bronze mirrors, and clay which came via Korea. More recently, Western sculptures called haniwa, which were erected techniques and artistic values have also added outside of tombs. their impact. The simple stick figures drawn on dotaku, However, what emerged from this history bells produced in the Yayoi period, as well as of assimilated ideas and know-how from other the murals adorning the inside walls of tombs cultures is an indigenous expression of taste in the Kofun period, represent the origins of that is uniquely Japanese. Japanese painting. Haniwa Haniwa are unglazed earthenware sculptures The Influence of Buddhism that were paced on Ancient Times and around the great and China mounded tombs (kofun) The first settlers of Japan, the Jomon people of Japan's rulers during the 4th to 7th centuries. -

あ - ん, Komainu and Niô…

Vol XI.3 Jul-Aug 2011 あ - ん, Komainu and Niô… Komainu (狛犬 literally “Korean dogs”) are figures resembling lions. The origin of this term is obscure since the guardian animals are lions rather than canines. They are placed in pairs in the inner sanctuary of a Shintō shrine. They appear at its portal, or on both sides of the entrance. When inside the Shintô sanctuary, they are called jinnai komainu 陣内狛犬 and are mostly made of wood or metal; The outside pair of stone lions, called sandō komainu 参道狛犬 (approach way komainu) are an extension of the former and are from a later tradition that broadly developed during the Edo period. They are believed to be the protectors of the sanctuary. Some of the guardian lions have a single horn, and this feature is also found on lions in China guarding the entrances of tombs. The common belief that all Shintô shrines have komainu is as false, as is the idea that Buddhist temples never have them: Kiyomizu-dera in Kyoto contains a Pair of shishi or komainu, part of the architecture of a temple’s gate. 17th century, attributed to Hidari Jingorô, famous carver of the nemuri beautiful pair of komainu, as do many other neko (« Sleeping cat”) at Nikkô Tôshô-gû shrine Buddhist precincts. Ni-ô (仁王 ) are the 2 muscular guardians posted at the entrance of Buddhist temples in Japan, Korea and China, in a separate structure, called niomon in Japan (the nio-gate). They are naked except for a piece of cloth or scarf around their waist often looped around their shoulder and whirling above their heads.