Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

71 Reggae Festival Guide 2006

71 71 ❤ ❤ Reggae Festival Guide 2006 Reggae Festival Guide 2006 Reggae Festival Guide 2006 RED, GOLD & GREEN MMEMORIESE M O R I E S Compiled by Wendy Russell Alton Ellis next started a group together: ALTON ELLIS AND THE There are reggae artists I treasure, with songs I FLAMES. The others had their careers too and I later started my play every radio show, no matter that the CD is no own group called WINSTON JARRETT AND THE RIGHTEOUS longer current. One such artist is roots man, WINSTON FLAMES. JARRETT and the RIGHTEOUS FLAMES, so I searched him out to fi nd what might be his own fond memory: We just had our history lesson! Can you imagine I grew up in Mortimer Planno, one of Rastafari’s most prominent Kingston, Jamaica elders, living just down the street? What about this in the government next memory - another likkle lesson from agent and houses there. manager, COPELAND FORBES: The streets are My memory of numbered First SUGAR MINOTT is Street and so on, from 1993 when I to Thirteenth Street. did a tour, REGGAE I lived on Fourth, SUPERFEST ‘93, ALTON ELLIS lived which had Sugar on 5th Street. He Minott, JUNIOR REID was much older and MUTABARUKA than me, maybe along with the 22. We were all DEAN FRASER-led good neighbors, 809 BAND. We did like a family so to six shows in East speak. MORTIMER Germany which PLANNO lived was the fi rst time Kaati on Fifth too and since the Berlin Wall Alton Ellis all the Rasta they came down, that an come from north, authentic reggae Sugar Minott south, east and west for the nyabinghi there. -

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari Annika McPherson Abstract: While the male focus of early literary representations of Rastafari tends to emphasize the movement’s emergence, goals or specific religious practices, more recent depictions of Rasta women in narrative fiction raise important questions not only regarding the discussion of gender relations in Rastafari, but also regarding the functions of literary representations of the movement. This article outlines a dialogical ‘reasoning’ between the different negotiations of gender in novels with Rastafarian protagonists and suggests that the characters’ individual spiritual journeys are key to understanding these negotiations within the gender framework of Rastafarian decolonial practices. Male-centred Literary Representations of Rastafari Since the 1970s, especially, ‘roots’ reggae and ‘dub’ or performance poetry have frequently been discussed as to their relations to the Rastafari movement – not only based on their lyrical content, but often by reference to the artists or poets themselves. Compared to these genres, the representation of Rastafari in narrative fiction has received less attention to date. Furthermore, such references often appear to serve rather descriptive functions, e.g. as to the movement’s philosophy or linguistic practices. The early depiction of Rastafari in Roger Mais’s “morality play” Brother Man (1954), for example, has been noted for its favourable representation of the movement in comparison to the press coverage of -

Coping with Babylon: the Proper Rastology (2005): Mutabaruka

Coping with Babylon: The Proper Rastology (2005): Mutabaruka, Half P... http://www.popmatters.com/pm/film/reviews/50538/coping-with-babylo... CALL FOR PAPERS: PopMatters seeks feature essays about any aspect of popular culture, present or past. Coping with Babylon: The Proper Rastology Director: Oliver Hill Cast: Mutabaruka, Half Pint, Luciano, Freddie McGregor, Barry Chevannes (2005) Rated: Unrated US DVD release date: 7 October 2007 (MVD) by Matthew Kantor Burning All Illusion Tonight Rastafari is known to the world through reggae music. Many interviewees in Oliver Hill’s Coping with Babylon: the Proper Rastology, who live Rastafari in their daily lives, cite Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, and Dennis Brown in particular as ambassadors of Jamaica’s great folk religion, never seeking to diminish these musicians’ roles in spreading the word. Rastafarian imagery has infiltrated popular culture not just through reggae and other kindred music, but also in the form of clothing, fashion, and general iconography. Despite the well-established co-option of the religion’s trappings and the tremendous popularity of many reggae, dub, and dancehall artists, Coping with Babylon: the Proper Rastology takes a sober, relatively non-musical path in broadcasting the views and roles of Rastafari in the early twenty-first century. Musicians including Luciano and Freddie McGregor are interviewed but so are leaders of various Rastafarian sects in addition to everyday followers of the faith in both Jamaica and New York. The film serves to remind viewers that Rastafarianism is a religion that deeply affects its practitioners and that music is only one aspect of it. And, like most religions, different sects vary in some of their more significant approaches and practices. -

Reggae As Subaltern Knowledge: Representations of Christopher Columbus As a Construction of Alternative Historical Memory

UCLA Mester Title Reggae as Subaltern Knowledge: Representations of Christopher Columbus as a Construction of Alternative Historical Memory Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7dg4f998 Journal Mester, 45(1) ISSN 0160-2764 Author Arbino, Daniel Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.5070/M3451029494 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Daniel Arbino Reggae as Subaltern Knowledge: Representations of Christopher Columbus as a Construction of Alternative Historical Memory Daniel Arbino University of Texas at Austin Birth of a music and a nation A casual reggae listener might consider the music to be upbeat and carefree, preaching messages of “getting together and feeling alright” and “not worrying about a thing, cause every little thing gonna be alright.”1 Such happy-go-lucky lyrics contribute to reggae’s interna- tional retail success, and they are used in ad campaigns to promote Jamaican tourism.2 However, in contrast to the aforementioned lyrics, reggae artists typically fused politics, spirituality, identity, and folk music to create highly discursive lyrics. Particularly during the era of newly independent Jamaica in the 1960s and 1970s, these complex lyrics reflected and forged a new society through media outlets such as the radio, dancehall parties, and deejay battles. The rise of reggae coincided with the construction of a new Jamaican society: reggae grew as a genre in Kingston’s urban shan- tytowns during the late 1960s, and the musical form responded to Jamaica’s independence from Great Britain in 1962. Reggae is influ- enced by other genres such as mento (a traditional Jamaican folk music that migrated with many from the country to the city), ska, rhythm and blues, and jazz. -

Writin' and Soundin' a Transnational Caribbean Experience

Oberlin Digital Commons at Oberlin Honors Papers Student Work 2013 Dubbin' the Literary Canon: Writin' and Soundin' A Transnational Caribbean Experience Warren Harding Oberlin College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Repository Citation Harding, Warren, "Dubbin' the Literary Canon: Writin' and Soundin' A Transnational Caribbean Experience" (2013). Honors Papers. 326. https://digitalcommons.oberlin.edu/honors/326 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Digital Commons at Oberlin. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Papers by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Oberlin. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Spring 2013 Dubbin’ the Literary Canon: Writin’ and Soundin’ A Transnational Caribbean Experience Warren Harding Candidate for Honors Africana Studies Africana Studies Honors Committee: Meredith Gadsby, Chair Gordon Gill Caroline Jackson Smith 2 ABSTRACT In the mid-1970s, a collective of Jamaican poets from Kingston to London began to use reggae as a foundational aesthetic to their poetry. Inspired by the rise of reggae music and the work of the Caribbean Artists Movement based London from 1966 to 1972, these artists took it upon themselves to continue the dialogue on Caribbean cultural production. This research will explore the ways in which dub poetry created an expressive space for Jamaican artists to complicate discussions of migration and colonialism in the transnational Caribbean experience. In order to do so, this research engages historical, ethnomusicological, and literary theories to develop a framework to analyze dub poetry. It will primarily pose the question, how did these dub poets expand the archives of Caribbean national production? This paper will suggest that by facilitating a dialogue among Jamaicans located between London and Kingston, dub poetry expanded the archives for Caribbean cultural production. -

Naming in Reggae Culture, the Example of Dub Poetry

Commonwealth Essays and Studies 36.1 | 2013 Appelation(s) “Dis Poem Shall Call Names Names”: Naming in Reggae Culture, the Example of Dub Poetry David Bousquet Electronic version URL: https://journals.openedition.org/ces/5274 DOI: 10.4000/ces.5274 ISSN: 2534-6695 Publisher SEPC (Société d’études des pays du Commonwealth) Printed version Date of publication: 1 September 2013 Number of pages: 45-55 ISSN: 2270-0633 Electronic reference David Bousquet, ““Dis Poem Shall Call Names Names”: Naming in Reggae Culture, the Example of Dub Poetry”, Commonwealth Essays and Studies [Online], 36.1 | 2013, Online since 16 April 2021, connection on 22 July 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/ces/5274 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ces. 5274 Commonwealth Essays and Studies is licensed under a Licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. “Dis Poem Shall Call Names Names” Naming in Reggae Culture, the Example of Dub Poetry The question of names and naming emerged as a crucial concern in the cultures of the African diaspora as a way to resist the anonymity and loss of identity imposed upon slaves. Through examples taken from reggae culture and the subgenre known as dub poetry, this paper looks at how names imply a political and poetic use of language in black At- lantic cultures. This is what I call cultural identity. An identity on its guard, in which the relationship with the Other shapes the self without fixing it under an oppressive force. That is what we see everywhere in the world: each people wants to declare its own identity. -

A History of Jamaican Creole in the Jamaican Broadcasting Media

Wissenschaftliche Arbeit im Fach Englisch A History of Jamaican Creole in the Jamaican Broadcasting Media vorgelegt von: Michael Westphal Prüfer: Prof. Dr. Christian Mair Big Up and tanks to: Prof. Mair for the tape recordings and guidance Axel for proof reading and feedback Philip for technical assistance Jamaica and Jamaican Broadcasting for a good time and inspiration Table of Content 1. Creole languages in the media 1 2. Outline of the study 4 3. Theoretical background 3.1 Different Theories for the description of the linguistic situation in Jamaican broadcasting 5 3.2 Diglossia 6 3.3 (Post –) Creole – Continuum 7 3.4 Acts of Identity 10 4. The special nature of broadcasting in the Jamaican mass media 12 5. Data 14 6. Macro-linguistic analysis 6.1 Methodology 16 6.2. Pre- Independence – late 1930’s to late 1950’s 6.2.1 Socio – historical background 17 6.2.2 Media background 18 6.2.3 Linguistic Analysis 19 6.2.4 Music 22 6.2.5 Conclusion 23 6.3. The Glorious Sixties 6.3.1 Socio – historical background 24 6.3.2 Media background 24 6.3.3 Linguistic Analysis 25 6.3.4 Music 28 6.3.5 Conclusion 30 6.4 Experiments with Socialism – the 1970’s 6.4.1 Socio – historical background 31 6.4.2 Media background 32 6.4.3 Linguistic Analysis 33 6.4.4 Music 37 6.4.5 Conclusion 38 6.5 The 1980’s – towards media liberalization 6.5.1 Socio – historical background 40 6.5.2 Media background 41 6.5.3 Linguistic Analysis 42 6.5.4 Music 48 6.5.5 Conclusion 50 6.6. -

Introduction L 3

i ntroduction The “Megarhetorics” of Global Development J. Blake Scott and Rebecca Dingo Waves crash over a pristine beach; birds sing cheerfully as the camera pans over lush tropical foliage. The serenity of the scene is quickly inter- rupted, however, by the sound of a helicopter and images of urban decay. Over the echo of chaos and gunshots, a TV reporter’s voice states: “The [Jamaican] government has called up the national reserves as civil unrest grips the nation this evening” (Life and Debt). The reporter pauses as the camera shows chaotic rioting, then cuts to a scene of women, children, and men injured and bleeding; we watch a set of Jamaican observers, who look not unlike those mired in the riots, surveying the chaos on their television. Over this set of concerned-looking citizens watching the violence, the re- porter continues: “Food and major commodities remain low. Several persons have been shot, or injured, or killed. Hospitals, airlines, and vendors are hurting from the wound[s] of violent protests. A team from the IMF [International Monetary Fund], which is currently in Jamaica, is wrapping up a four-day visit for a technical assessment of the country’s financial situation” Life( and Debt). The scene then shifts to a television set showing a man standing at a podium. In stark contrast to the previously depicted black Jamaican people 1 © 2012 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. 2 l J. Blake scott and rebecca Dingo dressed casually in bright colors and gazing passively at the television set, this white man, former director of the IMF Horst Kohler, wears a gray suit, stands straight, and speaks directly into the camera: “The issue is to make globalization work for the benefit of all. -

Untitled Will Be out in Di Near Near Future Tracks on the Matisyahu Album, I Did Something with Like Inna Week Time

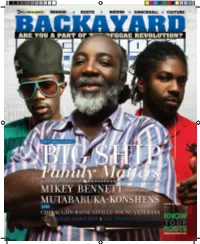

BACKAYARD DEEM TEaM Chief Editor Amilcar Lewis Creative/Art Director Noel-Andrew Bennett Managing Editor Madeleine Moulton (US) Production Managers Clayton James (US) Noel Sutherland Contributing Editors Jim Sewastynowicz (US) Phillip Lobban 3G Editor Matt Sarrel Designer/Photo Advisor Andre Morgan (JA) Fashion Editor Cheridah Ashley (JA) Assistant Fashion Editor Serchen Morris Stylist Judy Bennett Florida Correspondents Sanjay Scott Leroy Whilby, Noel Sutherland Contributing Photographers Tone, Andre Morgan, Pam Fraser Contributing Writers MusicPhill, Headline Entertainment, Jim Sewastynowicz, Matt Sarrel Caribbean Ad Sales Audrey Lewis US Ad Sales EL US Promotions Anna Sumilat Madsol-Desar Distribution Novelty Manufacturing OJ36 Records, LMH Ltd. PR Director Audrey Lewis (JA) Online Sean Bennett (Webmaster) [email protected] [email protected] JAMAICA 9C, 67 Constant Spring Rd. Kingston 10, Jamaica W.I. (876)384-4078;(876)364-1398;fax(876)960-6445 email: [email protected] UNITED STATES Brooklyn, NY, 11236, USA e-mail: [email protected] YEAH I SAID IT LOST AND FOUND It seems that every time our country makes one positive step forward, we take a million negative steps backward (and for a country with about three million people living in it, that's a lot of steps we are all taking). International media and the millions of eyes around the world don't care if it's just that one bad apple. We are all being judged by the actions of a handful of individuals, whether it's the politician trying to hide his/her indiscretions, to the hustler that harasses the visitors to our shores. It all affects our future. -

Bookkeeping: Discourses of Debt in Caribbean Canadian Literature By

Bookkeeping: Discourses of Debt in Caribbean Canadian Literature by Lisa Camille van der Marel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Department of English and Film Studies University of Alberta © Lisa Camille van der Marel, 2018 ABSTRACT This thesis examines representations of debt and obligation in works of Caribbean Canadian literature published between 1997 and 2007. It uses these representations to discuss the relationship between postcolonial, global, and diasporic approaches to cultural studies. These disciplinary distinctions draw explicit and implicit divisions between the colonial, the postcolonial, and the transnational as discrete historical moments in a teleologic progression. Against such divisions, literary works by David Chariandy, Ramabai Espinet, Dionne Brand, and Nalo Hopkinson suggest that colonial pasts do not remain in the past but continue to overdetermine the ‘transnational’ present. Intriguingly, each of these authors uses the language of debt and obligation to describe these temporal and geographical entanglements. This thesis draws on new economic criticism, memory studies, theories of recognition, treaty citizenship, and Afro-pessimism to argue firstly that Caribbean Canadian literature’s representations of debt refute emerging neo-Marxist theories of debt’s governmentality offered in response to the 2008 global financial crisis, and secondly, that they expose diaspora studies’ underlying valuation of individual autonomy and possessive individualism. By representing colonial pasts as outstanding and unpayable debts, fictional and nonfictional works dispute the seemingly clean breaks contemporary scholarship and political debates can draw between colonial pasts and transnational futures. Debt, at its simplest, is any exchange not brought to completion; Canada’s present is a space of incomplete—and incompletable—cultural, economic, and intellectual exchanges. -

Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CGU Theses & Dissertations CGU Student Scholarship Fall 2019 A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry Anthony Blacksher Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Africana Studies Commons, American Literature Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Poetry Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Television Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Blacksher, Anthony. (2019). A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry. CGU Theses & Dissertations, 148. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cgu_etd/148. doi: 10.5642/cguetd/148 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the CGU Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in CGU Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Matter of Life and Def: Poetic Knowledge and the Organic Intellectuals in Russell Simmons Presents Def Poetry By Anthony Blacksher Claremont Graduate University 2019 i Copyright Anthony Blacksher, 2019 All rights reserved ii Approval of the Dissertation Committee This dissertation has been duly read, reviewed, and critiqued by the Committee listed below, which hereby approves the manuscript of Anthony Blacksher as fulfilling the scope and quality requirements for meriting the degree of doctorate of philosophy in Cultural Studies with a certificate in Africana Studies.