'Stir It Up': Contestation and the Dialogue in the Artistic Practice Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representations of Conjoined Twins

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2015 Representations of conjoined twins Claire Marita Fletcher University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Fletcher, Claire Marita, Representations of conjoined twins, Master of Arts in Creative Writing thesis, Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, 2015. https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/ 4691 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. -

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence

In Defense of Rap Music: Not Just Beats, Rhymes, Sex, and Violence THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Crystal Joesell Radford, BA Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Professor Beverly Gordon, Advisor Professor Adrienne Dixson Copyrighted by Crystal Joesell Radford 2011 Abstract This study critically analyzes rap through an interdisciplinary framework. The study explains rap‟s socio-cultural history and it examines the multi-generational, classed, racialized, and gendered identities in rap. Rap music grew out of hip-hop culture, which has – in part – earned it a garnering of criticism of being too “violent,” “sexist,” and “noisy.” This criticism became especially pronounced with the emergence of the rap subgenre dubbed “gangsta rap” in the 1990s, which is particularly known for its sexist and violent content. Rap music, which captures the spirit of hip-hop culture, evolved in American inner cities in the early 1970s in the South Bronx at the wake of the Civil Rights, Black Nationalist, and Women‟s Liberation movements during a new technological revolution. During the 1970s and 80s, a series of sociopolitical conscious raps were launched, as young people of color found a cathartic means of expression by which to describe the conditions of the inner-city – a space largely constructed by those in power. Rap thrived under poverty, police repression, social policy, class, and gender relations (Baker, 1993; Boyd, 1997; Keyes, 2000, 2002; Perkins, 1996; Potter, 1995; Rose, 1994, 2008; Watkins, 1998). -

Paper Number: 63 May 2007 Before and After the Fall: Mapping Hong

Paper Number: 63 May 2007 Before and after the Fall: Mapping Hong Kong Cantopop in the Global Era Stephen Yiu-wai Chu Hong Kong Baptist University The author welcome comments from readers. Contact details: Stephen Yiu-wai Chu, Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong Email: [email protected] David C. Lam Institute for East-West Studies (LEWI) Hong Kong Baptist University (HKBU) LEWI Working Paper Series is an endeavour of David C. Lam Institute for East-West Studies (LEWI), a consortium with 28 member universities, to foster dialogue among scholars in the field of East-West studies. Globalisation has multiplied and accelerated inter-cultural, inter-ethnic, and inter-religious encounters, intentionally or not. In a world where time and place are increasingly compressed and interaction between East and West grows in density, numbers, and spread, East-West studies has gained a renewed mandate. LEWI’s Working Paper Series provides a forum for the speedy and informal exchange of ideas, as scholars and academic institutions attempt to grapple with issues of an inter-cultural and global nature. Circulation of this series is free of charge. Comments should be addressed directly to authors. Abstracts of papers can be downloaded from the LEWI web page at http://www.hkbu.edu.hk/~lewi/publications.html. Manuscript Submission: Scholars in East-West studies at member universities who are interested in submitting a paper for publication should send an article manuscript, preferably in a Word file via e-mail, as well as a submission form (available online) to the Series Secretary at the address below. -

Freddie Mcgregor & Toyan / Roots Radics

Freddie McGregor Roots Man Skanking / Roots Man Dubbing mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Reggae Album: Roots Man Skanking / Roots Man Dubbing Country: UK Released: 1982 MP3 version RAR size: 1560 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1940 mb WMA version RAR size: 1921 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 319 Other Formats: MIDI MPC AIFF DMF APE DXD MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Roots Man Skanking A –Freddie McGregor & Toyan Written-By – F. McGregor*, L. Thompson* Roots Man Dubbing B –Roots Radics* Written-By – L. Thompson* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Greensleeves Records Ltd. Copyright (c) – Greensleeves Records Ltd. Published By – Greensleeves Publishing Ltd. Published By – Sparta-Florida Recorded At – Harry J's Recording Studio Recorded At – Channel One Recording Studio Mixed At – Channel One Recording Studio Credits Backing Band [Backed By] – Roots Radics* Mixed By – Scientist Plated By – PAG Producer – Linval Thompson Notes ℗ & © 1982 Greensleeves Records Ltd. Published by Greensleeves Publishing/Sparta Florida Recorded at Harry J and Channel One Mixed at Channel One Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Runout, side A): GRED 84A1 PAG. Matrix / Runout (Runout, side B): GRED 84B PAG. Related Music albums to Roots Man Skanking / Roots Man Dubbing by Freddie McGregor Junjo - Wins The World Cup (The Final King Tubby's Session) Reggae King Tubby Meets Roots Radics - Dangerous Dub Reggae Freddie McGregor - Big Ship Reggae Al Campbell - All Kind Of People / Last Dance Reggae Freddie McGregor / Freddie & Brentford Rockers - Home Ward Bound / Home Ward Version Reggae Don Carlos - Day To Day Living Reggae Linval Thompson - Baby Father Reggae The Roots Radics - Radicfaction Reggae Hugh Mundell - Mundell Reggae Scientist vs. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

71 Reggae Festival Guide 2006

71 71 ❤ ❤ Reggae Festival Guide 2006 Reggae Festival Guide 2006 Reggae Festival Guide 2006 RED, GOLD & GREEN MMEMORIESE M O R I E S Compiled by Wendy Russell Alton Ellis next started a group together: ALTON ELLIS AND THE There are reggae artists I treasure, with songs I FLAMES. The others had their careers too and I later started my play every radio show, no matter that the CD is no own group called WINSTON JARRETT AND THE RIGHTEOUS longer current. One such artist is roots man, WINSTON FLAMES. JARRETT and the RIGHTEOUS FLAMES, so I searched him out to fi nd what might be his own fond memory: We just had our history lesson! Can you imagine I grew up in Mortimer Planno, one of Rastafari’s most prominent Kingston, Jamaica elders, living just down the street? What about this in the government next memory - another likkle lesson from agent and houses there. manager, COPELAND FORBES: The streets are My memory of numbered First SUGAR MINOTT is Street and so on, from 1993 when I to Thirteenth Street. did a tour, REGGAE I lived on Fourth, SUPERFEST ‘93, ALTON ELLIS lived which had Sugar on 5th Street. He Minott, JUNIOR REID was much older and MUTABARUKA than me, maybe along with the 22. We were all DEAN FRASER-led good neighbors, 809 BAND. We did like a family so to six shows in East speak. MORTIMER Germany which PLANNO lived was the fi rst time Kaati on Fifth too and since the Berlin Wall Alton Ellis all the Rasta they came down, that an come from north, authentic reggae Sugar Minott south, east and west for the nyabinghi there. -

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari Annika McPherson Abstract: While the male focus of early literary representations of Rastafari tends to emphasize the movement’s emergence, goals or specific religious practices, more recent depictions of Rasta women in narrative fiction raise important questions not only regarding the discussion of gender relations in Rastafari, but also regarding the functions of literary representations of the movement. This article outlines a dialogical ‘reasoning’ between the different negotiations of gender in novels with Rastafarian protagonists and suggests that the characters’ individual spiritual journeys are key to understanding these negotiations within the gender framework of Rastafarian decolonial practices. Male-centred Literary Representations of Rastafari Since the 1970s, especially, ‘roots’ reggae and ‘dub’ or performance poetry have frequently been discussed as to their relations to the Rastafari movement – not only based on their lyrical content, but often by reference to the artists or poets themselves. Compared to these genres, the representation of Rastafari in narrative fiction has received less attention to date. Furthermore, such references often appear to serve rather descriptive functions, e.g. as to the movement’s philosophy or linguistic practices. The early depiction of Rastafari in Roger Mais’s “morality play” Brother Man (1954), for example, has been noted for its favourable representation of the movement in comparison to the press coverage of -

Dancehall Dossier.Cdr

DANCEHALL DOSSIER STOP M URDER MUSIC DANCEHALL DOSSIER Beenie Man Beenie Man - Han Up Deh Hang chi chi gal wid a long piece of rope Hang lesbians with a long piece of rope Beenie Man Damn I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays I'm dreaming of a new Jamaica, come to execute all the gays Beenie Man Beenie Man - Batty Man Fi Dead Real Name: Anthony M Davis (aka ‘Weh U No Fi Do’) Date of Birth: 22 August 1973 (Queers Must Be killed) All batty man fi dead! Jamaican dancehall-reggae star Beenie All faggots must be killed! Man has personally denied he had ever From you fuck batty den a coppa and lead apologised for his “kill gays” music and, to If you fuck arse, then you get copper and lead [bullets] prove it, performed songs inciting the murder of lesbian and gay people. Nuh man nuh fi have a another man in a him bed. No man must have another man in his bed In two separate articles, The Jamaica Observer newspaper revealed Beenie Man's disavowal of his apology at the Red Beenie Man - Roll Deep Stripe Summer Sizzle concert at James Roll deep motherfucka, kill pussy-sucker Bond Beach, Jamaica, on Sunday 22 August 2004. Roll deep motherfucker, kill pussy-sucker Pussy-sucker:a lesbian, or anyone who performs cunnilingus. “Beenie Man, who was celebrating his Tek a Bazooka and kill batty-fucker birthday, took time to point out that he did not apologise for his gay-bashing lyrics, Take a bazooka and kill bum-fuckers [gay men] and went on to perform some of his anti- gay tunes before delving into his popular hits,” wrote the Jamaica Observer QUICK FACTS “He delivered an explosive set during which he performed some of the singles that have drawn the ire of the international Virgin Records issued an apology on behalf Beenie Man but within gay community,” said the Observer. -

National Malaysian Twin Registry - a Perfect Opportunity for Researchers to Study Nature Versus Nurture

Malaysian Family Physician 2008; Volume 3, Number 2 ISSN: 1985-207X (print), 1985-2274 (electronic) ©Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia Online version: http://www.ejournal.afpm.org.my/ News & Views NATIONAL MALAYSIAN TWIN REGISTRY - A PERFECT OPPORTUNITY FOR RESEARCHERS TO STUDY NATURE VERSUS NURTURE S Jahanfar Postdoctorate in Epidemiology, Public Health (UPM), PhD Obstetrics and Gynecology (NSW) Director of National Malaysian Twin Registry Corresponding address: Dr. Shayesteh Jahanfar, Lecturer, Department of Public Health, Royal College of Medicine Perak – University of Kuala Lumpur, No 3, Jalan Greentown, Ipoh, 30450, Perak, Malaysia. Tel: 05-243 2535, Fax: 05-243 2536, Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Jahanfar S. National Malaysian Twin Registry - a perfect opportunity for researchers to study nature versus nurture. Malaysian Family Physician. 2008;3(2):111-112 INTRODUCTION overall infant mortality, morbidity, and long term handicap.2 Intrauterine death of one foetus in a multiple gestation is A twin registry is a registry of twin pairs (monozygotic = MZ associated with significant morbidity and mortality in surviving and Dizygotic = DZ) who are willing to consider participating twin.5 Arrival of twins has an economic, social and in health-related research. Twins are able to help researchers psychological impact on families of twins.6 Vital statistics study the impact of genetic and environmental factors on health relevant to twins are needed to plan better services for twin and the treatment and prevention of disease in a special way. pregnancies and twins. Throughout the world, twin registries have been established by the governments via the National Health and Medical In efforts to solve the problem on aetiology of disease, twin Research in order to put researchers in touch with twins who studies have contributed greatly; since the early days of genetic might be willing to take part in particular projects. -

Most Requested Songs of 2015

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2015 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Ronson, Mark Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 2 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 3 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 4 Swift, Taylor Shake It Off 5 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 6 Williams, Pharrell Happy 7 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 8 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 9 Sheeran, Ed Thinking Out Loud 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 12 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 13 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 14 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 15 Mars, Bruno Marry You 16 Maroon 5 Sugar 17 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 18 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 19 Legend, John All Of Me 20 B-52's Love Shack 21 Isley Brothers Shout 22 DJ Snake Feat. Lil Jon Turn Down For What 23 Outkast Hey Ya! 24 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 25 Beatles Twist And Shout 26 Pitbull Feat. Ke$Ha Timber 27 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 28 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 29 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 30 Trainor, Meghan All About That Bass 31 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 32 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 33 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 34 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 35 Bryan, Luke Country Girl (Shake It For Me) 36 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 37 Lmfao Feat. -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

View Song List

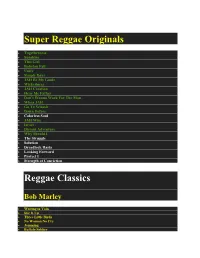

Super Reggae Originals Togetherness Sunshine This Girl Babylon Fall Unify Simple Days JAH Be My Guide Wickedness JAH Creation Hear Me Father Don’t Wanna Work For The Man Whoa JAH Go To Selassie Down Before Colorless Soul JAH Wise Israel Distant Adventure Why Should I The Struggle Solution Dreadlock Rasta Looking Forward Protect I Strength of Conviction Reggae Classics Bob Marley Waiting in Vain Stir It Up Three Little Birds No Woman No Cry Jamming Buffalo Soldier I Shot the Sherriff Mellow Mood Forever Loving JAH Lively Up Yourself Burning and Looting Hammer JAH Live Gregory Issacs Number One Tune In Night Nurse Sunday Morning Soon Forward Cool Down the Pace Dennis Brown Love and Hate Need a Little Loving Milk and Honey Run Too Tuff Revolution Midnite Ras to the Bone Jubilees of Zion Lonely Nights Rootsman Zion Pavilion Peter Tosh Legalize It Reggaemylitis Ketchie Shuby Downpressor Man Third World 96 Degrees in the Shade Roots with Quality Reggae Ambassador Riddim Haffe Rule Sugar Minott Never Give JAH Up Vanity Rough Ole Life Rub a Dub Don Carlos People Unite Credential Prophecy Civilized Burning Spear Postman Columbus Burning Reggae Culture Two Sevens Clash See Dem a Come Slice of Mt Zion Israel Vibration Same Song Rudeboy Shuffle Cool and Calm Garnet Silk Zion in a Vision It’s Growing Passing Judgment Yellowman Operation Eradication Yellow Like Cheese Alton Ellis Just A Guy Breaking Up is Hard to Do Misty in Roots Follow Fashion Poor and Needy