Paper Number: 63 May 2007 Before and After the Fall: Mapping Hong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong

Intercultural Communication Studies XXII: 1 (2013) R. MAK & C. CHAN Icons, Culture and Collective Identity of Postwar Hong Kong Ricardo K. S. MAK & Catherine S. CHAN Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong S.A.R., China Abstract: Icons, which take the form of images, artifacts, landmarks, or fictional figures, represent mounds of meaning stuck in the collective unconsciousness of different communities. Icons are shortcuts to values, identity or feelings that their users collectively share and treasure. Through the concrete identification and analysis of icons of post-war Hong Kong, this paper attempts to highlight not only Hong Kong people’s changing collective needs and mental or material hunger, but also their continuous search for identity. Keywords: Icons, Hong Kong, Hong Kong Chinese, 1997, values, identity, lifestyle, business, popular culture, fusion, hybridity, colonialism, economic takeoff, consumerism, show business 1. Introduction: Telling Hong Kong’s Story through Icons It seems easy to tell the story of post-war Hong Kong. If merely delineating the sky-high synopsis of the city, the ups and downs, high highs and low lows are at once evidently remarkable: a collective struggle for survival in the post-war years, tremendous social instability in the 1960s, industrial take-off in the 1970s, a growth in economic confidence and cultural arrogance in the 1980s and a rich cultural upheaval in search of locality before the handover. The early 21st century might as well sum up the development of Hong Kong, whose history is long yet surprisingly short- propelled by capitalism, gnawing away at globalization and living off its elastic schizophrenia. -

CHAPTER 3 Hong Kong Music Ecosphere

Abstract The people of Hong Kong experienced their deepest sense of insecurity and anxiety after the handover of sovereignty to Beijing. Time and again, the incapacity and lack of credibility of the SAR government has been manifested in various new policies or incidents. Hong Kong people’s anger and discontent with the government have reached to the peak. On July 1, 2003, the sixth anniversary of the hand-over of Hong Kong to China, 500,000 demonstrators poured through the streets of Hong Kong to voice their concerns over the proposed legislation of Article 23 and their dissatisfaction to the SAR government. And the studies of politics and social movement are still dominated by accounts of open confrontations in the form of large scale and organized rebellions and protests. If we shift our focus on the terrain of everyday life, we can find that the youth voice out their discontents by different ways, such as various kinds of media. This research aims to fill the gap and explore the relationship between popular culture and politics of the youth in Hong Kong after 1997 by using one of the local bands KingLyChee as a case study. Politically, it aims at discovering the hidden voices of the youth and argues that the youth are not seen as passive victims of structural factors such as education system, market and family. Rather they are active and strategic actors who are capable of negotiating with and responding to the social change of Hong Kong society via employing popular culture like music by which the youth obtain their pleasure of producing their own meanings of social experience and the pleasure of avoiding the social discipline of the power-bloc. -

Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐Wai's Days Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by PDXScholar PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal Volume 3 Issue 1 Identity, Communities, and Technology: On the Article 18 Cusp of Change 2009 Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 Julie Nakama Portland State University Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/mcnair Recommended Citation Nakama, Julie (2009) "Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046," PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal: Vol. 3: Iss. 1, Article 18. 10.15760/mcnair.2009.127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Portland State University McNair Research Journal 2009 Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 by Julie Nakama Faculty Mentor: Mark Berrettini Citation: Nakama, Julie. Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar‐wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046. Portland State University McNair Scholars Online Journal, Vol. 3, 2009: pages [127‐153] McNair Online Journal Page 1 of 27 Time after Time: Exploring Temporality and Identity in Wong Kar-wai’s Days of Being Wild, In the Mood for Love, and 2046 Julie Nakama Mark Berrettini, Faculty Mentor Wong Kar-wai is part of a generation of Hong Kong filmmakers whose work can be seen in response to two pivotal events in Hong Kong, the 1984 signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration detailing Hong Kong’s return to China in 1997 and the events of Tiananmen Square in 1989. -

Influences of Music's “Chinese Style” Trend on Related Industry's Profit

Influences of Music’s “Chinese Style” Trend on Related Industry’s Profit Making Strategy Sizhe Liu Shanghai World Foreign Language Academy, Shanghai 201101, China Email: [email protected] Abstract: “Chinese style” is a new music genre that has developed rapidly in China since the 20th century. As its populari- ty rises, which forms a “Chinese style” trend, the music gradually becomes commercialized and thus affects the profit mak- ing strategy of related firms. In the research, the author is going to explain and evaluate these strategies and their causes. Keywords: Chinese style, popular music, industry, audience 1. Introduction The rapid development of “Chinese style” popular music in China has greatly changed the field of popular music since 21 century. This popular music genre, involving traditional poetry, traditional melody, traditional culture, modern singing method, modern arrangement, and modern concept, attracts a huge number of young audiences. The author, in a new angle of view, analyses Chinese style music in the perspective of economics. Because many related industries of Chinese style music want to seize this opportunity of the music genre’s popularity, various strategies are used to make a profit. The effectiveness of these strategies and their influences to the future development of Chinese style music are worth exploring. Therefore, in this study, the author analyses and evaluates the profit making strategies of the related firms. 2. Literature review From databases such as CNKI, Wanfang, and VIP, the author found that early researches have fully analyzed the music musical features of Chinese style music in both aspects of composition and lyrics. -

Ain't Nothin' but the Blues

14 發光的城市 A R O U N D T O W N FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 14, 2008 • TAIPEI TIMES Shun Kikuta, left, and Lance Reegan-Diehl Band, far right, appear tomorrow at Blues Bash 5, which takes place at the Dream Community in Sijhih. PHOTOS COURTESY OF BLUES BASH Band schedule Outdoor showcase 3:10pm The Money Shot Horns 3:30pm Jamsbee 3:45pm Blues Vibrations Annie Yi and Laurence 4:05pm Musashino Minnie and Small Package Huang have been 4:20pm Black Sheep caught in the act ... of 4:40pm Lance Reegan-Diehl Band holding hands. 4:55pm David Chen and the Muddy Basin Ramblers PHOTOS: TAIPEI TIMES 5:15pm Nacomi 5:30pm The Rising Hedons 5:50pm Shun Kikuta Indoor performances Theater stage 6:35pm BoPoMoFo (ㄅㄆㄇㄈ) 7:25pm Jamsbee aiwan�s paparazzi whole affair. After studying 8:15pm Musashino Minnie and Small Package outdid themselves this Huang�s nose, the geomancers 9:05pm Lance Reegan-Diehl Band week by portraying determined that he must be 9:55pm Nacomi T actress Annie Yi (伊能 good in bed. That�s right, in 10:45pm Shun Kikuta 靜) as a partying harlot who Taiwan its not big hands or 11:30pm Jam Session doesn�t want anything to do big feet, but a sharp nose that with her husband, Harlem reveals sexual prowess. Coffee shop stage Yu (庾澄慶), and their son, The subtext of the whole Harry (哈利), after the Liberty “scandal,” it seems to Pop 6:15pm The Money Shot Horns Times (自由時報) (the Taipei Stop�s feminist take, is this: 7:05pm Blues Vibrations Times’ sister newspaper) Men, you may leave your 7:55pm David Chen and the Muddy Basin Ramblers and Next Magazine (壹週 family back in Taiwan and 8:45pm Ah-Yi 刊) published photos of the have a second wife (or 9:35pm Black Sheep singer and movie star walking girlfriend) and live it up in 10:25pm The Rising Hedons hand-in-hand with fellow China, but Yi is blazing new Taiwanese actor Laurence ground and proving that Huang (黃維德). -

Kung Fu Panda Movie Download in Tamil

1 / 4 Kung Fu Panda Movie Download In Tamil Kung Fu Panda: The Paws of Destiny Season 01 All Episodes in Hindi Dubbed Free Download Mp4 480p & 720p HD. May 29, 2019 I J K L. Set after the events .... Tamil New Movies · Tamil HD Movies · Tamil Dubbed Movies · Tamil Web Series · logo image. Tags › Kung Fu Panda 3 Tamil Movie Online .... Kung Fu Panda 3 Full Hd Movie Hindi Dubbed Download, Download the ... Download Cannonball Run II (1984) (Tamil) Full Movie on CooLMoviez - The .. kung fu panda 3 scene tamil ( Tamil Cartoon Movie) 00:04:56 · kung fu panda 3 ... Kung Fu Panda 3 full movie download in Tamil 00:01:48 · Kung Fu Panda 3 .... Kung Fu Panda (Widescreen) on DVD from DreamWorks Home Ent. Directed by Mark Osborne and John Stevenson. Staring Jack Black, Lucy Liu, Ian McShane .... Watch online or download Hollywood movie Rob B Hood 2006 Hindi Dubbed. ... such as Rush Hour, Shanghai Noon, The Karate Kid and Kung Fu Panda, and he boasts more than ... Jackie chan adventures tamil episode 6 at June 22, 2018. Video kung fu panda 2 full movie in tamil hd download - OKClips.Net - वेब पर सर्वश्रेष्ठ मुफ्त फिल्में, वीडियो, टीवी .... Kung Fu Panda 3 is American-Chinese film written by Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berge ... Download The SpongeBob Movie Sponge on the Run 2020.. Kung Fu panda 3 (2016) - Skadooshing The Spirit Warrior Scene Tamil 8 Movieclips Tamil by ᴍᴏᴠɪᴇᴄʟɪᴘs ᴛᴀᴍɪʟ / ʜɪ sᴛᴜᴅɪᴏs. Download .... Ilsa the Tigress of Siberia (1977), one of the best movie ever, that you may watch online .. -

The Globalization of K-Pop: the Interplay of External and Internal Forces

THE GLOBALIZATION OF K-POP: THE INTERPLAY OF EXTERNAL AND INTERNAL FORCES Master Thesis presented by Hiu Yan Kong Furtwangen University MBA WS14/16 Matriculation Number 249536 May, 2016 Sworn Statement I hereby solemnly declare on my oath that the work presented has been carried out by me alone without any form of illicit assistance. All sources used have been fully quoted. (Signature, Date) Abstract This thesis aims to provide a comprehensive and systematic analysis about the growing popularity of Korean pop music (K-pop) worldwide in recent years. On one hand, the international expansion of K-pop can be understood as a result of the strategic planning and business execution that are created and carried out by the entertainment agencies. On the other hand, external circumstances such as the rise of social media also create a wide array of opportunities for K-pop to broaden its global appeal. The research explores the ways how the interplay between external circumstances and organizational strategies has jointly contributed to the global circulation of K-pop. The research starts with providing a general descriptive overview of K-pop. Following that, quantitative methods are applied to measure and assess the international recognition and global spread of K-pop. Next, a systematic approach is used to identify and analyze factors and forces that have important influences and implications on K-pop’s globalization. The analysis is carried out based on three levels of business environment which are macro, operating, and internal level. PEST analysis is applied to identify critical macro-environmental factors including political, economic, socio-cultural, and technological. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Commencement Program

Sunday, the Sixteenth of May, Two Thousand and Ten ten o’clock in the morning ~ wallace wade stadium Duke University Commencement ~ 2010 One Hundred Fifty-Eighth Commencement Notes on Academic Dress Academic dress had its origin in the Middle Ages. When the European universities were taking form in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, scholars were also clerics, and they adopted Mace and Chain of Office robes similar to those of their monastic orders. Caps were a necessity in drafty buildings, and Again at commencement, ceremonial use is copes or capes with hoods attached were made of two important insignia given to Duke needed for warmth. As the control of universities University in memory of Benjamin N. Duke. gradually passed from the church, academic Both the mace and chain of office are the gifts costume began to take on brighter hues and to of anonymous donors and of the Mary Duke employ varied patterns in cut and color of gown Biddle Foundation. They were designed and and type of headdress. executed by Professor Kurt J. Matzdorf of New The use of academic costume in the United Paltz, New York, and were dedicated and first States has been continuous since Colonial times, used at the inaugural ceremonies of President but a clear protocol did not emerge until an Sanford in 1970. intercollegiate commission in 1893 recommended The Mace, the symbol of authority of the a uniform code. In this country, the design of a University, is made of sterling silver throughout. gown varies with the degree held. The bachelor’s Significance of Colors It is thirty-seven inches long and weighs about gown is relatively simple with long pointed Colors indicating fields of eight pounds. -

Labor Chief Speeds up Work Permit Procedure

Ad-Phuket dot com K. Anna AV Volume 13 Issue 18 News Desk - Tel: 076-236555May 6 - 12, 2006 Daily news at www.phuketgazette.net 25 Baht The Gazette is published in association with Labor Chief Crowne Plaza speeds up work permit IN THIS ISSUE procedure NEWS: THAI and Bangkok Air- sold for B3.7bn By Natcha Yuttaworawit ways sign deal; Beware of fakes cops, Police Chief By Gazette Staff PHUKET CITY: Work permits warns. Pages 2 & 3 are being renewed in just 15 min- INSIDE STORY: Rising oil KARON: The Crowne Plaza utes and new work permits ap- prices and the knock-on effect Karon Beach Phuket resort has proved faster than ever thanks for Phuket. Pages 4 & 5 been bought by Dubai-listed ho- to streamlining of procedures at AROUND THE ISLAND: If the cap tel and resort investment com- the Phuket Provincial Employ- fits… Page 8 pany Kingdom Hotel Invest- ment Office (PPEO). AROUND THE REGION: Revis- ments (KHI), which is headed by PPEO Chief Boonchok iting the Khao Lak blues. Saudi Arabia’s Prince Alwaleed Maneechot explained that before Page 9 Bin Talal Bin Abdul Aziz Al-Saud. implementing the new proce- PEOPLE: Off The Wall. KHI paid US$98.5 million dures he had consulted with em- Pages 10 & 11 (3.7 billion baht) for the property, ployment officers for a month in including US$30.5 million (1.1 order to determine the most effi- LIFESTYLE: Summer fashion. billion baht) in debt. cient way to process work per- Pages 12 & 13 Prince Alwaleed was listed mits. -

Big Four Coming to the Venetian Macao for Third Time Hong Kong Cantopop Stars to Perform at Venetian Theatre

Big Four Coming to The Venetian Macao for Third Time Hong Kong Cantopop stars to perform at Venetian Theatre (Macao, Oct. 30, 2014) – Cantopop stars Big Four will perform one night only at The Venetian® Macao’s Venetian Theatre on Friday, Nov. 21 with its WOW An Evening date with Big Four. Tickets go on sale Oct. 31 at all Cotai Ticketing box offices*. The band’s return to The Venetian Macao is part of an exciting weekend of superstar entertainment at the popular integrated resort. Sunday, Nov. 23 will also see the return of boxing icon Manny Pacquiao, as he takes on the undefeated Chris Algieri at Clash in Cotai II. Tickets are still available, priced HKD/MOP 880-24,080, so fans are urged to grab tickets now at www.cotaiticketing.com. Both events give visitors a chance to experience spectacular live entertainment while enjoying the convenience of The Venetian Macao’s diverse selection of world-class shopping and dining choices. Formed in 2009, Big Four is made up of friends Dicky Cheung, Andy Hui, William So and Edmond Leung. The Hong Kong actor-singers are set to entertain the Macao audience this November with WOW An Evening date with Big Four, a concert filled with their greatest hits, including “Big Four,” “Powerless to Help,” “The Pain of Men,” and “Man Should Not Make Woman Cry.” Tickets for the 8 p.m., Nov. 21 performance of WOW An Evening date with Big Four at the Venetian Theatre go on sale Friday, Oct. 31 via Cotai Ticketing and can be purchased for HKD/MOP 780 (A Reserve), 580 (B Reserve) and 380 (C Reserve); HKD/MOP 88 adds a round trip Cotai Water Jet ferry ticket between Hong Kong and * The Venetian Macao – Cotai Arena and Main Lobby box offices; Four Seasons Hotel Macao – The Plaza™ Macao box office; Sands® Macao – L1 box office; Sands® Cotai Central – Sheraton Main Lobby and Holiday Inn Main Lobby Page 1 of 3 Macao. -

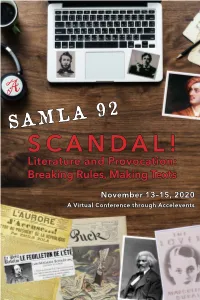

SCANDAL! Literature and Provocation: Breaking Rules, Making Texts

A SAMLA 92 SCANDAL! Literature and Provocation: Breaking Rules, Making Texts November 13–15, 2020 A Virtual Conference through Accelevents SAMLA WELCOMES OUR 2020 EXHIBITORS Welcome from the President and Executive Director 1 Award Winners 4 Schedule of Conference Events 8 Plenary Speaker Profile 10 Plenary and Presidential Events 12 Past Presidents’ Sessions 13 Conference Schedule 15 Subject Index 70 Participant Index 80 Committee Lists 87 Business Meeting Agenda 93 Executive Committee Nominees 94 SAMLA 93 Guidelines, Deadlines, and Considerations 98 SAMLA WOULD LIKE TO THANK FOR 26 YEARS OF SUPPORT AND COllaBORATION SOUTH ATLANTIC MODERN LANGUAGE ASSOCIATION STAFF LeeAnne M. Richardson—Executive Director Dan Abitz—Associate Director Esther Stuart—Conference Manager Shari Arnold—Assistant Conference Manager I-Hsien “Shannon” Lee—Membership Manager Mike Saye—Assistant Membership Manager Donna Pennington—Production and Design Manager SOUTH ATLANTIC REVIEW STAFF R. Barton Palmer—Editor Marta Hess—Associate Editor M. Allison Wise—Managing Editor PROGRAM COVER ATTRIBUTIONS “Henry David Thoreau - Stencil” by Iso Brown FR (CC BY-NC 2.0) “Le feulliton de l’été - Madame Bovary” (Permission Granted by Babelio) Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0) “Oscar Wilde” by bixentro (CC BY 2.0) © South Atlantic Modern Language Association 2020 This program was designed, compiled, and edited by SAMLA Staff at Georgia State University. 1 WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT Dear SAMLA Members and Conference Guests, Welcome to SAMLA 92, the first-ever virtual meeting of the South Atlantic Modern Language Association. Despite the numerous challenges that we have faced throughout this uncertain year, it is thanks to your commitment and the foresight and planning of our Executive Committee that this year’s conference is possible.