February 9, 2020 Falling Real Interest Rates, Rising Debt: a Free Lunch?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Quarterly

Forecasting the Effects of Reduced Defense Spending Peter Irel’and and Chtitopher Omk ’ I. INTRODUCTION $1 cut in defense spending acts to decrease the total demand for goods and services in each period by $1. The end of the Cold War provides the United Of course, so long as the government has access to States with an opportunity to cut its defense the same production technologies that are available spending significantly. Indeed, the Bush Administra- to the private sector, this prediction of the tion’s 1992-1997 Future Years Defense Program neoclassical model does not change if instead the (presented in 1991 and therefore referred to as the government produces the defense services itself.’ “1991 plan”) calls for a 20 percent reduction in real defense spending by 1997. Although expenditures A permanent $1 cut in defense spending also related to Operation Desert Storm have delayed the reduces the government’s need for tax revenue; it implementation of the 199 1 plan, policymakers con- implies that taxes can be cut by $1 in each period. tinue to call for defense cutbacks. In fact, since Bush’s Households, therefore, are wealthier following the plan was drafted prior to the collapse of the Soviet cut in defense spending; their permanent income in- Union, it seems likely that the Clinton Administra- creases by $b1. According to the permanent income tion will propose cuts in defense spending that are hypothesis, this $1 increase in permanent income even deeper than those specified by the 1991 plan. induces households to increase their consumption by This paper draws on both theoretical and empirical $1 in every period, provided that their labor supply economic models to forecast the effects that these does not change. -

Corporate Bonds and Debentures

Corporate Bonds and Debentures FCS Vinita Nair Vinod Kothari Company Kolkata: New Delhi: Mumbai: 1006-1009, Krishna A-467, First Floor, 403-406, Shreyas Chambers 224 AJC Bose Road Defence Colony, 175, D N Road, Fort Kolkata – 700 017 New Delhi-110024 Mumbai Phone: 033 2281 3742/7715 Phone: 011 41315340 Phone: 022 2261 4021/ 6237 0959 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.vinodkothari.com 1 Copyright & Disclaimer . This presentation is only for academic purposes; this is not intended to be a professional advice or opinion. Anyone relying on this does so at one’s own discretion. Please do consult your professional consultant for any matter covered by this presentation. The contents of the presentation are intended solely for the use of the client to whom the same is marked by us. No circulation, publication, or unauthorised use of the presentation in any form is allowed, except with our prior written permission. No part of this presentation is intended to be solicitation of professional assignment. 2 About Us Vinod Kothari and Company, company secretaries, is a firm with over 30 years of vintage Based out of Kolkata, New Delhi & Mumbai We are a team of qualified company secretaries, chartered accountants, lawyers and managers. Our Organization’s Credo: Focus on capabilities; opportunities follow 3 Law & Practice relating to Corporate Bonds & Debentures 4 The book can be ordered by clicking here Outline . Introduction to Debentures . State of Indian Bond Market . Comparison of debentures with other forms of borrowings/securities . Types of Debentures . Modes of Issuance & Regulatory Framework . -

Interest-Rate-Growth Differentials and Government Debt Dynamics

From: OECD Journal: Economic Studies Access the journal at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/19952856 Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics David Turner, Francesca Spinelli Please cite this article as: Turner, David and Francesca Spinelli (2012), “Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics”, OECD Journal: Economic Studies, Vol. 2012/1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_studies-2012-5k912k0zkhf8 This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. OECD Journal: Economic Studies Volume 2012 © OECD 2013 Interest-rate-growth differentials and government debt dynamics by David Turner and Francesca Spinelli* The differential between the interest rate paid to service government debt and the growth rate of the economy is a key concept in assessing fiscal sustainability. Among OECD economies, this differential was unusually low for much of the last decade compared with the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s. This article investigates the reasons behind this profile using panel estimation on selected OECD economies as means of providing some guidance as to its future development. The results suggest that the fall is partly explained by lower inflation volatility associated with the adoption of monetary policy regimes credibly targeting low inflation, which might be expected to continue. However, the low differential is also partly explained by factors which are likely to be reversed in the future, including very low policy rates, the “global savings glut” and the effect which the European Monetary Union had in reducing long-term interest differentials in the pre-crisis period. -

Sample Debt Validation Letter (Send Via Certified Mail, Return Receipt Requested)

Sample Debt Validation Letter (Send via certified mail, return receipt requested) Date: Your Name Your Address Your City, State, Zip Collection Agency Name Collection Agency Address Collection Agency City, State, Zip RE: Account # (Fill in Account Number) To Whom It May Concern: Be advised this is not a refusal to pay, but a notice that your claim is disputed and validation is requested. Under the Fair Debt collection Practices Act (FDCPA), I have the right to request validation of the debt you say I owe you. I am requesting proof that I am indeed the party you are asking to pay this debt, and there is some contractual obligation that is binding on me to pay this debt. This is NOT a request for “verification” or proof of my mailing address, but a request for VALIDATION made pursuant to 15 USC 1692g Sec. 809 (b) of the FDCPA. I respectfully request that your offices provide me with competent evidence that I have any legal obligation to pay you. At this time I will also inform you that if your offices have or continue to report invalidated information to any of the three major credit bureaus (Equifax, Experian, Trans Union), this action might constitute fraud under both federal and state laws. Due to this fact, if any negative mark is found or continues to report on any of my credit reports by your company or the company you represent, I will not hesitate in bringing legal action against you and your client for the following: Violation of the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act and Defamation of Character. -

Corporate Bond Markets: A

Staff Working Paper: [SWP4/2014] Corporate Bond Markets: A Global Perspective Volume 1 April 2014 Staff Working Paper of the IOSCO Research Department Authors: Rohini Tendulkar and Gigi Hancock1 This Staff Working Paper should not be reported as representing the views of IOSCO. The views and opinions expressed in this Staff Working Paper are those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization of Securities Commissions or its members. For further information please contact: [email protected] 1 Rohini Tendulkar is an Economist and Gigi Hancock is an Intern in IOSCO’s Research Department. They would like to thank Werner Bijkerk, Shane Worner and Luca Giordano for their assistance. 1 About this Document The IOSCO Research Department produces research and analysis on a range of securities markets issues, risks and developments. To support these efforts, the IOSCO Research Department undertakes a number of annual information mining exercises including extensive market intelligence in financial centers; risk roundtables with prominent members of industry and regulators; data gathering and analysis; the construction of quantitative risk indicators; a survey on emerging risks to regulators, academics and market participants; and review of the current literature on risks by experts. Developments in corporate bond markets have been flagged a number of times during these exercises. In particular, the lack of data on secondary market trading and, in general, issues in emerging market corporate bond markets, have been highlighted as an obstacle in understanding how securities markets are functioning and growing world-wide. Furthermore, the IOSCO Board has recognized, through establishment of a long-term finance project, the important contribution IOSCO and its members can and do make in ensuring capital markets play a leading role in supporting long term investment in both growth and emerging and developed economies. -

Nber Working Papers Series

NBER WORKING PAPERS SERIES WAS THERE A BUBBLE IN THE 1929 STOCK MARKET? Peter Rappoport Eugene N. White Working Paper No. 3612 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 February 1991 We have benefitted from comments made on earlier drafts of this paper by seminar participants at the NEER Summer Institute and Rutgers University. We are particularly indebted to Charles Calomiris, Barry Eicherigreen, Gikas Hardouvelis and Frederic Mishkiri for their suggestions. This paper is part of NBER's research program in Financial Markets and Monetary Economics. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #3612 February 1991 WAS THERE A BUBBLE IN THE 1929 STOCK MARKET? ABSTRACT Standard tests find that no bubbles are present in the stock price data for the last one hundred years. In contrast., historical accounts, focusing on briefer periods, point to the stock market of 1928-1929 as a classic example of a bubble. While previous studies have restricted their attention to the joint behavior of stock prices and dividends over the course of a century, this paper uses the behavior of the premia demanded on loans collateralized by the purchase of stocks to evaluate the claim that the boom and crash of 1929 represented a bubble. We develop a model that permits us to extract an estimate of the path of the bubble and its probability of bursting in any period and demonstrate that the premium behaves as would be expected in the presence of a bubble in stock prices. -

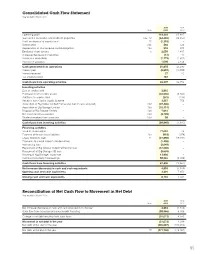

Reconciliation of Net Cash Flow to Movement in Net Debt Year Ended 31 March 2015

Consolidated Cash Flow Statement Year ended 31 March 2015 2015 2014 Note £000 £000 Operating profit 114,203 67,887 Gain on the revaluation of investment properties 13a, 14 (64,465) (28,350) Profit on disposal of surplus land 15 (1,318) – Depreciation 13b 566 526 Depreciation of finance lease capital obligations 13a 918 974 Employee share options 6 2,059 1,437 (Increase)/decrease in inventories (14) 10 Increase in receivables (1,172) (1,652) Increase in payables 1,098 2,458 Cash generated from operations 51,875 43,290 Interest paid (9,692) (10,558) Interest received 27 20 Tax credit received 187 – Cash flows from operating activities 42,397 32,752 Investing activities Sale of surplus land 2,815 – Purchase of non-current assets (42,555) (8,460) Additions to surplus land (231) (136) Receipts from Capital Goods Scheme 3,557 756 Acquisition of Big Yellow Limited Partnership (net of cash acquired) 13d (37,406) – Acquisition of Big Storage Limited 13a (15,114) – Disposal of Big Storage Limited 13a 7,614 – Net investment in associates 13d (3,709) – Dividend received from associate 13d 89 – Cash flows from investing activities (84,940) (7,840) Financing activities Issue of share capital 77,094 42 Payment of finance lease liabilities 13a (918) (974) Equity dividends paid 11 (27,890) (19,591) Payments to cancel interest rate derivatives (1,408) – Refinancing fees (2,649) – Repayment of Big Yellow Limited Partnership loan (57,000) – Repayment of Big Storage AIB loan (9,659) – Drawing of Big Storage Lloyds loan 13,900 – Increase/(reduction) in borrowings -

Economic Chapters of the 85Th Annual Report, June 2015

85th Annual Report 1 April 2014–31 March 2015 Basel, 28 June 2015 This publication is available on the BIS website (www.bis.org/publ/arpdf/ar2015e.htm). Also published in French, German, Italian and Spanish. © Bank for International Settlements 2015. All rights reserved. Limited extracts may be reproduced or translated provided the source is stated. ISSN 1021-2477 (print) ISSN 1682-7708 (online) ISBN 978-92-9197-064-3 (print) ISBN 978-92-9197-066-7 (online) Contents Letter of transmittal ..................................................... 1 Overview of the economic chapters .................................. 3 I. Is the unthinkable becoming routine? ............................. 7 The global economy: where it is and where it may be going ...................... 9 Looking back: recent evolution ............................................ 9 Looking ahead: risks and tensions .......................................... 10 The deeper causes ............................................................ 13 Ideas and perspectives . 13 Excess financial elasticity .................................................. 15 Why are interest rates so low? ............................................. 17 Policy implications ............................................................ 18 Adjusting frameworks ..................................................... 18 What to do now? ........................................................ 21 Conclusion . 22 II. Global financial markets remain dependent on central banks 25 Further monetary accommodation but diverging -

Government Debt

Government Debt Douglas W. Elmendorf Federal Reserve Board N. Gregory Mankiw Harvard University and NBER January 1998 This paper was prepared for the Handbook of Macroeconomics. We are grateful to Michael Dotsey, Richard Johnson, David Wilcox, and Michael Woodford for helpful comments. The views expressed in this paper are our own and not necessarily those of any institution with which we are affiliated. Abstract This paper surveys the literature on the macroeconomic effects of government debt. It begins by discussing the data on debt and deficits, including the historical time series, measurement issues, and projections of future fiscal policy. The paper then presents the conventional theory of government debt, which emphasizes aggregate demand in the short run and crowding out in the long run. It next examines the theoretical and empirical debate over the theory of debt neutrality called Ricardian equivalence. Finally, the paper considers the various normative perspectives about how the government should use its ability to borrow. JEL Nos. E6, H6 Introduction An important economic issue facing policymakers during the last two decades of the twentieth century has been the effects of government debt. The reason is a simple one: The debt of the U.S. federal government rose from 26 percent of GDP in 1980 to 50 percent of GDP in 1997. Many European countries exhibited a similar pattern during this period. In the past, such large increases in government debt occurred only during wars or depressions. Recently, however, policymakers have had no ready excuse. This episode raises a classic question: How does government debt affect the economy? That is the question that we take up in this paper. -

Introduction Section 4000.1

Introduction Section 4000.1 This section contains product profiles of finan- Each product profile contains a general cial instruments that examiners may encounter description of the product, its basic character- during the course of their review of capital- istics and features, a depiction of the market- markets and trading activities. Knowledge of place, market transparency, and the product’s specific financial instruments is essential for uses. The profiles also discuss pricing conven- examiners’ successful review of these activities. tions, hedging issues, risks, accounting, risk- These product profiles are intended as a general based capital treatments, and legal limitations. reference for examiners; they are not intended to Finally, each profile contains references for be independently comprehensive but are struc- more information. tured to give a basic overview of the instruments. Trading and Capital-Markets Activities Manual February 1998 Page 1 Federal Funds Section 4005.1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION commonly used to transfer funds between depository institutions: Federal funds (fed funds) are reserves held in a bank’s Federal Reserve Bank account. If a bank • The selling institution authorizes its district holds more fed funds than is required to cover Federal Reserve Bank to debit its reserve its Regulation D reserve requirement, those account and credit the reserve account of the excess reserves may be lent to another financial buying institution. Fedwire, the Federal institution with an account at a Federal Reserve Reserve’s electronic funds and securities trans- Bank. To the borrowing institution, these funds fer network, is used to complete the transfer are fed funds purchased. To the lending institu- with immediate settlement. -

Daily Comment

Daily Comment By Bill O’Grady, Thomas Wash, and Patrick Fearon-Hernandez, CFA Looking for something to read? See our Reading List; these books, separated by category, are ones we find interesting and insightful. We will be adding to the list over time. [Posted: April 21, 2020—9:30 AM EDT] Global equity markets are lower this morning. The EuroStoxx 50 is down 2.5% from its last close. In Asia, the MSCI Asia Apex 50 closed down 1.8% from the prior close. Chinese markets were lower, with the Shanghai Composite down 0.9% and the Shenzhen Composite down 0.8%. U.S. equity index futures are signaling a lower open. With 54 companies having reported, the S&P 500 Q1 earnings stand at $32.90, lower than the $35.51 forecast for the quarter. The forecast reflects a 10.0% decrease from Q1 2019 earnings. Thus far this quarter, 70.4% of the companies have reported earnings above forecast, while 29.6% have reported earnings below forecast. Happy Tuesday! Or if not “happy,” at least things are “interesting.” U.S. oil prices yesterday not only went negative, but deeply negative. As always, we discuss the coronavirus crisis and its latest implications below, along with reports of a new government in Israel and indications that North Korean leader Kim Jong Un may be dying. COVID-19: Official data show confirmed cases have risen to 2,495,994 worldwide, with 171,652 deaths and 658,802 recoveries. In the United States, confirmed cases rose to 787,960, with 42,364 deaths and 73,527 recoveries. -

Debt Collection Guide Update

Debt Collection Guide Update This Update includes new information you should know when dealing with debt collectors. 1. In New York, a debt collector cannot collect or attempt to collect on a payday loan. Payday loans are illegal in New York. A payday loan is a high-interest loan borrowed against your next paycheck. To apply for a payday loan, you need to have a checking account and proof of income. In New York State, most payday loans are handled by phone or online. If a collection agency tries to collect on a payday loan, visit nyc.gov/dca or contact 311 to file a complaint with DCA. 2. Beware of debt collection companies or companies working with debt collection companies that offer you a credit card if you repay, in part or in full, an old debt that may have expired. Companies may use terms like “Fresh Start Program” or “Balance Transfer Program” to describe offers to transfer your old debt to a new credit card account after you make a certain number of payments. If you accept the credit card offer and start making pay- ments, the debt collection agency’s time limit (statute of limitations) for suing you to collect this debt will restart. The company offering the credit card may not tell you that this is a consequence of getting the credit card. See the section What Should You Do When a Debt Collection Agency Contacts You? for information about statute of limitations. 3. It is illegal for a debt collection agency to use “caller ID spoofing.” Some debt collection agencies are using spoofed (or faked) phone numbers to disguise their identities on caller ID.