“Gateway Earth” – Low Cost Access to Interplanetary Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The “Farm:” an Inflatable Centrifuge Biology Research Module on the International Space Station

The “Farm:” An Inflatable Centrifuge Biology Research Module on the International Space Station M.Thangavelu1, L. Simurda2 As the sole manned laboratory in Low Earth Orbit, permanently operating in microgravity and largely unprotected by the Earth's atmosphere, the International Space Station serves as an unparalleled platform for studying the effects of low or zero-gravity and the space radiation environment on biological systems as well as developing, testing and certifying sturdy and reliable systems for long duration missions such as ambitious interplanetary expeditions planned for the future. Earth- bound research, automated research aboard satellites and short missions into low- altitude orbits cannot replicate long-term ISS experiments. Abandoning or de- orbiting the station, even in 2020, leaves the international scientific and engineering community bereft of a manned station in orbit and destroys any opportunity for conducting long-term microgravity and radiation experiments requiring human oversight in space. The United States should invest in extending the station's life by a minimum of 15 years from present by attaching an inflatable "Farm" centrifuge module to equip biologists, psychologists and engineers with the tools required to investigate these questions and more. At a time when humankind has only begun exploring the effects of the space environment on biological systems, it is essential that we not abandon the only empirical research facility in operation today and instead begin vigorously pursuing research in this area that is of vital importance to all humanity, not only in the basic and applied sciences but also in international collaboration. I. Introduction In June 2010, President Barack Obama announced a novel vision for NASA and proposed extending the life of the International Space Station (ISS) until at least 2020. -

The Space Race Continues

The Space Race Continues The Evolution of Space Tourism from Novelty to Opportunity Matthew D. Melville, Vice President Shira Amrany, Consulting and Valuation Analyst HVS GLOBAL HOSPITALITY SERVICES 369 Willis Avenue Mineola, NY 11501 USA Tel: +1 516 248-8828 Fax: +1 516 742-3059 June 2009 NORTH AMERICA - Atlanta | Boston | Boulder | Chicago | Dallas | Denver | Mexico City | Miami | New York | Newport, RI | San Francisco | Toronto | Vancouver | Washington, D.C. | EUROPE - Athens | London | Madrid | Moscow | ASIA - 1 Beijing | Hong Kong | Mumbai | New Delhi | Shanghai | Singapore | SOUTH AMERICA - Buenos Aires | São Paulo | MIDDLE EAST - Dubai HVS Global Hospitality Services The Space Race Continues At a space business forum in June 2008, Dr. George C. Nield, Associate Administrator for Commercial Space Transportation at the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), addressed the future of commercial space travel: “There is tangible work underway by a number of companies aiming for space, partly because of their dreams, but primarily because they are confident it can be done by the private sector and it can be done at a profit.” Indeed, private companies and entrepreneurs are currently aiming to make this dream a reality. While the current economic downturn will likely slow industry progress, space tourism, currently in its infancy, is poised to become a significant part of the hospitality industry. Unlike the space race of the 1950s and 1960s between the United States and the former Soviet Union, the current rivalry is not defined on a national level, but by a collection of first-mover entrepreneurs that are working to define the industry and position it for long- term profitability. -

Highlights in Space 2010

International Astronautical Federation Committee on Space Research International Institute of Space Law 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren c/o CNES 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren UNITED NATIONS 75015 Paris, France 2 place Maurice Quentin 75015 Paris, France Tel: +33 1 45 67 42 60 Fax: +33 1 42 73 21 20 Tel. + 33 1 44 76 75 10 E-mail: : [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] Fax. + 33 1 44 76 74 37 URL: www.iislweb.com OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS URL: www.iafastro.com E-mail: [email protected] URL : http://cosparhq.cnes.fr Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is responsible for promoting international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space and assisting developing countries in using space science and technology. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs P. O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26060-4950 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5830 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.unoosa.org United Nations publication Printed in Austria USD 15 Sales No. E.11.I.3 ISBN 978-92-1-101236-1 ST/SPACE/57 *1180239* V.11-80239—January 2011—775 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS UNITED NATIONS OFFICE AT VIENNA Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law Progress in space science, technology and applications, international cooperation and space law UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 UniTEd NationS PUblication Sales no. -

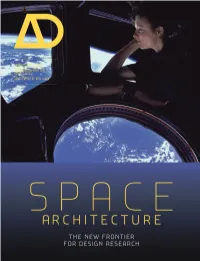

Space Architecture the New Frontier for Design Research

ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN GUEST-EDITED BY NEIL LEACH SPACE ARCHITECTURE THE NEW FRONTIER FOR DESIGN RESEARCH 06 / 2014 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2014 ISSN 0003-8504 PROFILE NO 232 ISBN 978-1118-663301 IN THIS ISSUE 1 ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN GUEST-EDITED BY NEIL LEACH SPACE ARCHITECTURE: THE NEW FRONTIER FOR DESIGN RESEARCH 5 EDITORIAL 30 MoonCapital: Helen Castle Life on the Moon 100 Years After Apollo Andreas Vogler 6 ABOUT THE GUEST-EDITOR Neil Leach 36 Architecture For Other Planets A Scott Howe 8 INTRODUCTION Space Architecture: Th e New Frontier 40 Buzz Aldrin: Mission to Mars for Design Research Neil Leach Neil Leach 46 Colonising the Red Planet: 16 What Next for Human Space Flight? Humans to Mars in Our Time Brent Sherwood Robert Zubrin 20 Planet Moon: Th e Future of 54 Terrestrial Space Architecture Astronaut Activity and Settlement Neil Leach Madhu Th angavelu 64 Space Tourism: Waiting for Ignition Ondřej Doule 70 Alpha: From the International Style to the International Space Station Constance Adams and Rod Jones EDITORIAL BOARD Will Alsop Denise Bratton Paul Brislin Mark Burry André Chaszar Nigel Coates Peter Cook Teddy Cruz Max Fordham Massimiliano Fuksas Edwin Heathcote Michael Hensel Anthony Hunt Charles Jencks Bob Maxwell Brian McGrath Jayne Merkel Peter Murray Mark Robbins Deborah Saunt Patrik Schumacher Neil Spiller Leon van Schaik Michael Weinstock 36 Ken Yeang Alejandro Zaera-Polo 2 108 78 Being a Space Architect: 108 3D Printing in Space Astrotecture™ Projects for NASA Neil Leach Marc M Cohen 114 Astronauts Orbiting on Th eir Stomachs: 82 Outside the Terrestrial Sphere Th e Need to Design for the Consumption Greg Lynn FORM: N.O.A.H. -

Highlights in Space 2010

International Astronautical Federation Committee on Space Research International Institute of Space Law 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren c/o CNES 94 bis, Avenue de Suffren 75015 Paris, France 2 place Maurice Quentin 75015 Paris, France UNITED NATIONS Tel: +33 1 45 67 42 60 75039 Paris Cedex 01, France E-mail: : [email protected] Fax: +33 1 42 73 21 20 Tel. + 33 1 44 76 75 10 URL: www.iislweb.com E-mail: [email protected] Fax. + 33 1 44 76 74 37 OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS URL: www.iafastro.com E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://cosparhq.cnes.fr Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs is responsible for promoting international cooperation in the peaceful uses of outer space and assisting developing countries in using space science and technology. United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs P. O. Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel: (+43-1) 26060-4950 Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5830 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.unoosa.org United Nations publication Printed in Austria USD 15 Sales No. E.11.I.3 ISBN 978-92-1-101236-1 ST/SPACE/57 V.11-80947—March*1180947* 2011—475 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR OUTER SPACE AFFAIRS UNITED NATIONS OFFICE AT VIENNA Highlights in Space 2010 Prepared in cooperation with the International Astronautical Federation, the Committee on Space Research and the International Institute of Space Law Progress in space science, technology and applications, international cooperation and space law UNITED NATIONS New York, 2011 UniTEd NationS PUblication Sales no. -

Russian-Ukrainian Dnepr Program's Opportunities for Commercial

Russian-Ukrainian Dnepr Program’s Opportunities For Commercial Space Projects Presented by Dr. Ighor K. Uzhinsky ATK Launch Systems April 13, 2007 An advanced weapon and space systems company The world's leading supplier of solid propulsion systems and the nation's largest manufacturer of ammunition. An Advanced Weapon and Space Systems Company Approved for Public Release ATK History An advanced weapon and space systems company Hercules Acquisition of E.I. DuPont Hercules Powder Co. Aerospace Hercules Incorporated Incorporated Division Aerospace Co. Acquisition of Ordnance Operations 1802 1912 1977 1995 of Boeing Alfred Nobel Eastern 2001 Invents Dynamite Co. Dynamite 1902 Acquisition of Blount Acquisition of 1866 Acquisition of Mission International Inc. GASL & Research Corporation ammunitionAmmunition businessBusiness Micro Craft (MRC) 2001 2003 2004 Spinoff from Honeywell Honeywell Enters Honeywell Defense Business Systems Group 1940 1983 1990 1999 2006 Acquisition of Acquisition of SAT, Inc. Pressure Systems Inc. (PSI, ABLE, PCI) 2002 2004 Split backBack to Thiokol Morton Thiokol Thiokol Cordant Purchase by Acquisition of Acquisition Chemical Corp Merger Corporation Technologies Alcoa Thiokol Propulsion of COI COI 1989 1926 1982 1998 2000 2001 2003 Approved for Public Release ATK Corporate Profile An advanced weapon and space systems company • $3.5 billion aerospace and • Operations in 21 states defense company • Diversified customer base • ~15,000 employees • Leading positions in… • Headquarters in Edina, MN • Launch systems • Ranked -

US Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts

Federal Aviation Administration 2008 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts: Vehicles, Technologies, and Spaceports January 2008 HQ-08368.INDD 2008 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts About FAA/AST About the Office of Commercial Space Transportation The Federal Aviation Administration’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation (FAA/AST) licenses and regulates U.S. commercial space launch and reentry activity, as well as the operation of non-federal launch and reentry sites, as authorized by Executive Order 12465 and Title 49 United States Code, Subtitle IX, Chapter 701 (formerly the Commercial Space Launch Act). FAA/AST’s mission is to ensure public health and safety and the safety of property while protecting the national security and foreign policy interests of the United States during commercial launch and reentry operations. In addition, FAA/AST is directed to encourage, facilitate, and promote commercial space launches and reentries. Additional information concerning commercial space transportation can be found on FAA/AST’s web site at http://www.faa.gov/about/office_org/headquarters_offices/ast/. Federal Aviation Administration Office of Commercial Space Transportation i About FAA/AST 2008 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts NOTICE Use of trade names or names of manufacturers in this document does not constitute an official endorsement of such products or manufacturers, either expressed or implied, by the Federal Aviation Administration. ii Federal Aviation Administration Office of Commercial Space Transportation 2008 U.S. Commercial Space Transportation Developments and Concepts Contents Table of Contents Introduction . .1 Space Competitions . .1 Expendable Launch Vehicle Industry . .2 Reusable Launch Vehicle Industry . -

November 2014 No

C A R I B B E A N On-line C MPASS NOVEMBER 2014 NO. 230 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore SSeeee sstorytory oonn ppageage 1166 MIRA NENCHEVA OCTOBER 2014 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 2 The Caribbean’s Monthly Look at Sea & Shore www.caribbeancompass.com NOVEMBER 2014 • NUMBER 230 MONTSERRAT YACHT CLUB BRIAN SAMUEL DEPARTMENTS Info & Updates ......................4 The Caribbean Sky ...............36 Business Briefs .......................9 Cooking with Cruisers ..........38 Regatta News........................ 13 Readers’ Forum .....................39 Sailor’s Horoscope ................ 30 Calendar of Events ...............40 Compass Comics .................30 What’s on My Mind ............... 40 Montserrat YC Book Reviews ........................32 Caribbean Market Place .....42 The club that could ................ 8 Look Out For… ......................35 Classified Ads ....................... 46 Timing… Meridian Passage .................35 Advertisers’ Index .................46 … is everything .....................22 NOVEMBER 2014 CARIBBEAN COMPASS PAGE 3 Caribbean Compass is published monthly by Compass Publishing Ltd., P.O. Box 175 BQ, CHRIS DOYLE Bequia, St. Vincent & the Grenadines. Tel: (784) 457-3409, Fax: (784) 457-3410, [email protected], www.caribbeancompass.com Editor...........................................Sally Erdle Art, Design & Production......Wilfred Dederer [email protected] [email protected] Assistant Editor...................Elaine Ollivierre Accounting............................Shellese -

MOON VILLAGE Conceptual Design of a Lunar Habitat

CDF STUDY REPORT MOON VILLAGE Conceptual Design of a Lunar Habitat CDF-202(A) Issue 1.1 September 2020 Moon Village CDF Study Report: CDF-202(A) – Issue 1.1 September 2020 page 1 of 185 CDF Study Report Moon Village Conceptual Design of a Lunar Habitat ESA UNCLASSIFIED – Releasable to the Public Moon Village CDF Study Report: CDF-202(A) – Issue 1.1 September 2020 page 2 of 185 This study is based on the ESA CDF Open Concurrent Design Tool (OCDT), which is a community software tool released under ESA licence. All rights reserved. Further information and/or additional copies of the report can be requested from: A. Makaya ESA/ESTEC/TEC-MSP Postbus 299 2200 AG Noordwijk The Netherlands Tel: +31-(0)71-5653721 Fax: [email protected] For further information on the Concurrent Design Facility please contact: I.Roma ESA/ESTEC/TEC-SYE Postbus 299 2200 AG Noordwijk The Netherlands Tel: +31-(0)71-5658453 Fax: +31-(0)71-5656024 [email protected] FRONT COVER Study Logo showing Stylised Lunar Habitats with Earth in the background ESA UNCLASSIFIED – Releasable to the Public Moon Village CDF Study Report: CDF-202(A) – Issue 1.1 September 2020 page 3 of 185 STUDY TEAM This study was performed in the ESTEC Concurrent Design Facility (CDF) by the following interdisciplinary team: TEAM LEADER R. Biesbroek, TEC-SYE ADVANCED H. Lakk, TEC-SF POWER K. Stephenson, CONCEPTS A. Barco, TEC-EPM LIFE SUPPORT B. Lamaze, TEC-MMG RADIATION M. Vuolo, M. Holmberg, TEC-EPS MISSION M. Landgraf, STRUCTURES D. -

Commercial Crew Program Overview

, , KSC ENGINEERING ~ AND TECHNOLOGY Commercial Crew Program Overview Rick Russell Materials Science Division Kennedy Space Center 32 nd HIGH TEMPLE Workshop January 31, 2012 Palm Springs, CA ~ Agenda KSC ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY • Program Goals and Objectives • List of Pa rtners • Requirements Structure • Materia'is and Processes Requirements and Verfication • Overview of Space Act Agreements for Spacecraft ~ CCP Approach KSC ENGINEERING AND TECHNOLOGY Fiscal Year 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 Demo/Test Flights ~ Commercial Crew l.-'UJIi'I_~1<~"?.:JW"~i#'~~~,>~...r....w...~ ~~i>W:;6_~ ~«~~fIr ---- ... ---- Q ---- .-...... .. Goals: Facilitate the development of a U.S. commercial crew space transportation capability Stimulates U.S. space transportation industry and encourages the availability of space transportation services to NASA and others Objectives: Safe, reliable, and cost effective access to and from low Earth orbit (LEO) and the International Space Station (ISS) by mid-decade Investing in U.S. aerospace industry crew transportation system (CTS) design and development Mature the design and certify U.S. CTS capabilities Roadmap ~ KSC ENGINEERING ANO TECHNOLOGY FY10 FYll FY12 FY13 FY14 FY15 FY16 CCDevl Element Design BlueOri in Boein CCDev2 Sierra Nevada Element S eX Design ULA ATK Integrated Design and Early Development Design Phase ···.~N Early Development, Demonstration & FlightTest Activities -----, I r-----~-~---~----....,: DTEC ~;.;:;.;,=~=~=:r.=.:===t.=.::.:.::.==.:.:.....tl Phase & I "------------ --:---'1 Initial ISS I I Missions I Transition Potential Initial : to Services I I _ Space Act Agreements KSC ENGINEERING ANa TECHNOLOGY • Partnerships for CCDevl and CCDev2 were established via Space Act Agreements • For CCDev2 there are 7 partners - Funded • Blue Origin • Boeing • Sierra Nevada • SpaceX - Unfunded • United Launch Alliance • ATK • Excalibur Almaz, Inc. -

Manned Sample Return Mission to Phobos

Manned Sample Return Mission to Phobos: a Technology Demonstration for Human Exploration of Mars Natasha Bosanac Ana Diaz Victor Dang Frans Ebersohn Purdue University Massachusetts Institute of Technology Oregon State University University of Michigan 701 West Stadium Avenue 77 Massachusetts Avenue 1500 SW Jefferson Way 1320 Beal Avenue West Lafayette, IN 47907, USA Cambridge, MA 02139, USA Corvallis, OR 97331, USA Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA 765-494-7864 617-909-0644 541-737-1000 318-229-6347 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Stefanie Gonzalez Jay Qi Nicholas Sweet Norris Tie University of Colorado Boulder California Institute of Technology Concordia University University of California LA 429 UCB, ECAE 1B02 1200 East California Blvd 1455 De Maisonneuve Blvd. W 405 Hilgard Avenue Boulder, CO 80309-0429, USA Pasadena, CA 91125, USA Montreal, Canada, H3G 1M8 Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 414-795-6063 585-520-2995 514-825-5861 408-624-6859 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Gianluca Valentino Abigail Fraeman Alison Gibbings Tyler Maddox CERN BE-ABP Washington University in St.Louis ASCL, University of Strathclyde, University of Alabama Route de Meyrin 1 Brookins Drive, Campus Box 1169 James Weir Building, 301 Sparkman Drive Geneve 23 CH 1211 St Louis, MO 63130, USA 75 Montrose Street, Glasgow, UK Huntsvile, AL 35899, USA (+41) 227 67 1327 314-935-4625 (+44) 141-548-2326 256-961-7081 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] -

Commercial Spaceflight and Advanced Propulsion

Commercial Spaceflight and Advanced Propulsion Commercial Crew Development (CCDev1) • Sierra Nevada Corporaon (SpaceDev) – Development of the Dream Chaser spaceplane – $20M for building and tes>ng Engineering Test Arcle – Leverages NASA HL-20 airframe – Launch vehicle: Atlas V – Hybrid Rocket – Seven crew members • Robert Bigelow • Expandable Space Staon Modules – Inflatable modules are easier to launch – Based on technology developed at NASA: TransHab Program • Prototypes: – Genesis I • 1/3 size inflatable structure • Launched July 12, 2006 • Expanded to twice its diameter (4.4 m) – Genesis II • Same size as Genesis I • Launched June 28, 2007 • Enhanced sensors • Addi>onal layer for thermal control • Increased reliability Sundancer/BA 330 • Occupancy – 3 people – long term – 6 people – short term • Protec>on – Radiaon – Ballis>c • Four large windows • Environmental Systems • Solar Power • Propulsion – Manuevering – De-orbing • Es>mated launch: 2014? Space Ship Two • Spaceplane – VSS Enterprise – VSS Voyager (planned) • Hybrid Rockets • Peak Al>tude: 110 mi White Knight Two • Jet powered aircra – VMS EVE – VMS Spirit of Steve Fossed • Launch Al>tude: 9.5 mi • Suborbital Space Tourism – Ticket: $200 K – Down payment: $20 K • Spaceport – Partnership with New Mexico – $200 million – Training ground for tourists Lynx • Two person • $95k ($20k deposit) >cket price • Al>tude 100 mi. • Take off/lands like airplane • Mark I test flight: 2014? • Poten>ally four flights/day • Kerosene and LOX engines X-Racer • Designed for Rocket Racing League • Two seats