Leonora Carrington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archipelagobkcat

Tarjei Vesaas THE BIRDS Translated from the Norwegian by Michael Barnes & Torbjørn Støverud archipelago books archipelagofall 2015 / spring books 2016 archipelago books fall 2015 /spring 2016 frontlist The Folly / Ivan Vladislavi´c . 2 Private Life / Josep Maria de Sagarra / Mary Ann Newman . 4 Tristano Dies: A Life / Antonio Tabucchi / Elizabeth Harris . 6 A General Theory of Oblivion / José Eduardo Agualusa / Daniel Hahn . 8 Broken Mirrors / Elias Khoury / Humphrey Davies . 10 Absolute Solitude / Dulce María Loynaz / James O’Connor . 12 The Child Poet / Homero Aridjis / Chloe Aridjis . 14 Newcomers / Lojze Kovacˇicˇ / Michael Biggins . 16 The Birds / Tarjei Vesaas / Torbjørn Støverud and Michael Barnes . 18 Distant Light / Antonio Moresco / Richard Dixon . 20 Something Will Happen, You’ll See / Christos Ikonomou / Karen Emmerich . .22 My Struggle: Book Five / Karl Ove Knausgaard / Don Bartlett . 24 Wayward Heroes / Halldór Laxness / Philip Roughton . 26 recently published . 28 backlist . 40 forthcoming . 72 subscribing to archipelago books . 74 how to donate to archipelago books . 74 individual orders . 75 donors . 76 board of directors, advisory board, & staff . 80 In the tradition of Elias Canetti, a tour de force of the imagination . —André Brink Vladislavi´c is a rare, brilliant writer . His work eschews all cant . Its sheer verve, the way it burrows beneath ossified forms of writing, its discipline and the distance it places between itself and the jaded preoccupations of local fiction, distinguish it . —Sunday Times (South Africa) Vladislavi´c’s cryptic, haunting tale echoes Jorge Luís Borges and David Lynch, drawing readers into its strange depths . —Publishers Weekly The Folly is mysterious, lyrical, and wickedly funny – a masterful novel about loving and fearing your neighbor . -

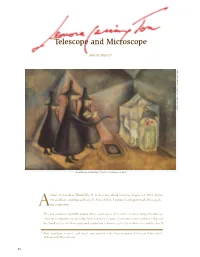

Telescope and Microscope

Telescope and Microscope Alberto Blanco* Private collection. © Estate of Leonora Carrington The Birdmen of Burnley, 45 x 65 cm (oil on canvas). midst the horror of World War II, in the entry dated Tuesday, August 24, 1943, of her extraordinary autobiographical tale, Down Below, Leonora Carrington made this surpris Aing statement: This last sentence, rightfully quoted often, speaks to us of an artist, a human being who did not settle for seeing only part of reality. To the contrary, Leonora Carrington, interested in the Big and the Small —that which in traditional symbolism is known as the Great Mysteries and the Small * Poet, translator, essayist, and visual artist; member of the National Sys tem of Creators of Art (SNCA), [email protected]. 50 Mysteries— never wanted to ignore the great scientific or philosophical themes. Throughout her long, intense life, she was just as interested in astronomy as in astrology, in quantum physics as in the mysteries of the psyche; and at the same time, she never turned her back on what could be considered the minutiae and the details of daily life: her family, her home, her beloved objects, her friends, her pets, her plants. © Estate of Leonora Carrington Private collection. In Leonora Carrington, a profoundly romantic artist —and here, I mean the great English romanticism, that of William Blake, for example— and an eminently practical person co existed without any contradiction. Also found together were a profound sense of humor —also very English, consisting frequently of talking very seriously about the most absurd topics— and the most serious determination to do work that never admitted of the slightest vacillation and suffered no foolishness at all. -

Worldwide Reading on September 8 Th, 2014

© Laura Poitras Liberty and Recognition for Edward Snowden Worldwide Reading on September 8 th, 2014 Angola José Eduardo Agualusa Argentina Eduardo Sguiglia Australia Brian Castro | Richard Flanagan | Gail Jones | Mike A Manifesto for the Truth by Edward Snowden Shuttleworth | Herbert Wharton Austria Haimo L. Handl | Josef Haslinger | Elfriede Jelinek | Eva Menasse | Haralampi Oroschakoff In a very short time, the world has learned much about unaccount- Bahrain Ameen Saleh Belgium Stefan Hertmans Bosnia-Herzegovina Faruk Šehi Brazil Ricardo Azevedo Bulgaria Ilija Trojanow | able secret agencies and about sometimes illegal surveillance pro- Tzveta Sofronieva Canada Brian Brett | Michael Day | Paul Dutton | Greg Gatenby | Michael Ondaatje | Madeleine Thien | Miriam Toews grams. Sometimes the agencies even deliberately try to hide their Chile Ariel Dorfman China Xiaolu Guo | Lian Yang | Liao Yiwu Colombia Winston Morales Chavarro | Rafael Patiño Góez | Fernando surveillance of high officials or the public. While the NSA and GCHQ Rendón | Laura Restrepo Cyprus Stephanos Stephanides Denmark Christian Jungersen | Pia Tafdrup | Janne Teller Egypt Mekkawi seem to be the worst offenders – this is what the currently available Said Estonia Hasso Krull | Jüri Talvet Finland JK Ihalainen France Camille de Toledo | Abdelwahab Meddeb | Mariette Navarro | documents suggest – we must not forget that mass surveillance is a global problem in need of global solutions. Christian Salmon Germany Jan Assmann | Güner Yasemin Balci | Wilhelm Bartsch | Marica Bodroži | Thomas Böhm | Mirko Bonné | Such programs are not only a threat to privacy, they also threaten Martin Buchholz | Irene Dische | Ute Frevert | Jochen Gerz | Christian Grote | Finn-Ole Heinrich | Ulrich Horstmann | Rolf Hosfeld | Florian freedom of speech and open societies. -

Hirstory of Comunism Revizie 16 Iunie.Indd

HISTORY OF COMMUNISM IN EUROPE HISTORY OF COMMUNISM IN EUROPE ADVISORY BOARD Dennis Deletant (London, Great Britain), Adrian Cioroianu (Bucharest, Romania), Zoe Petre (Bucharest, Romania), Cristian Pârvulescu (Bucharest, Romania), Lukasz Kaminski (Warsaw, Poland), Maria Schmidt (Budapest, Hungary), Hubertus Knabe (Berlin, Germany); Nicolae Manolescu (Paris/ Bucharest France/Romania), William Totok (Berlin, Germany), Daniel Barbu (Bucharest, Romania), Matei Cazacu (Paris, France), Stéphane Courtois (Paris, France) EDITOR IN CHIEF Dalia Báthory ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Camelia Runceanu Journal edited by Th e Institute for the Investigation of Communist Crimes and the Memory of the Romanian Exile (Bucharest) HISTORY OF COMMUNISM IN EUROPE Vol. V – 2014 Narratives of Legitimation in Totalitarian Regimes – Heroes, Villains, Intrigues and Outcomes ¤ ¤ Zeta Books, Bucharest www.zetabooks.com © 2015 Zeta Books for the present edition. © 2015 Th e copyrights to the essays in this volume belong to the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronical or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN: 978-606-8266-96-1 (paperback) ISBN: 978-606-8266-97-8 (electronic) ISSN: 2069-3192 (paperback) ISSN: 2069-3206 (electronic) TABLE OF CONTENTS ARGUMENT Dalia BÁTHORY: Weaving the Narrative Strings of the Communist Regimes – Building Society with Bricks of Stories . 7 I. HEROES AND VILLAINS – DEVELOPING THE CHARACTERS Ștefan BOSOMITU: Becoming in the Age of Proletariat. Th e Identity Dilemmas of a Communist Intellectual Th roughout Autobiographical Texts. Case Study: Tudor Bugnariu . 17 Renata Jambrešić KIRIN: Yugoslav Women Intellectuals: From a Party Cell to a Prison Cell. -

Studia Culturae

STUDIA CULTURAE ZDENKA KALNICKA PhD, professor Ostrava University ART AND GENDER IDENTITY Автор анализирует картину Леоноры Каррингтон «А затем мы увидели дочь Минотавра» («And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur») в сопоставлении с образами Минотавра в работах Пабло Пикассо. Она использует методологические принципы гендерного анализа с целью обнаружить гендерные аспекты классического мифа о Минотавре, демонстрируя тем самым традиционную конструкцию половой идентичности через биполярность маскулинности и феминнисти, обнаруженную в работах Пикассо. Работа Л. Каррингтон дает возможность автору проанализировать, каким образом художник трансформирует античный миф о Минотавре, деконструирует традиционную поляризацию маскулинности и фемининности и предлагает оригинальную интерпретацию половой идентичности. Ключевые слова: Минотавр, античный миф, архетип, пол, сюрреализм, Пабло Пикассо, Л. Каррингтон. Introduction What kind of message about gender identity is passed by the ancient myth of Minotaur? Why did this figure become so important for surrealism? Is there any difference between its incorporation and depiction by male artists, such as Pablo Picasso, and female artists, such as Leonora Carrington? What can we learn about their views on gender identity through interpretation of their artworks? In the first part, we describe the ancient myth of Minotaur, concentrating on its gender aspects. In the second part, we explain the significance of the Minotaur figure for surrealism, in particular for Pablo Picasso and document his understanding of gender identity through interpretation of his works with the Minotaur theme. Before the interpretation of the work of Leonora Carrington, we briefly point out the view on femininity spread among surrealists and its consequence for female artists in this movement. The central part is devoted to interpretation of the artwork of Leonora Carrington… And Then We Saw the Daughter of the Minotaur aiming to find out her particular way of deconstructing gender identity. -

Archipelago Books

archipelago books fall 2018 / spring 2019 archipelago books fall 2018/spring 2019 frontlist My Struggle: Book Six / Karl Ove Knausgaard / Don Bartlett & Martin Aitken . 2 Pan Tadeusz / Adam Mickiewicz / Bill Johnston . 4 An Untouched House / Willem Frederik Hermans / David Colmer . 6 Horsemen of the Sands / Leonid Yuzefovich / Marian Schwartz . 8 The Storm / Tomás González / Andrea Rosenberg . 10 The Barefoot Woman / Scholastique Mukasonga / Jordan Stump . 12 Good Will Come From the Sea / Christos Ikonomou / Karen Emmerich . 14 Flashback Hotel / Ivan Vladislavic´ . 16 Intimate Ties: Two Novellas / Robert Musil / Peter Wortsman . 18 A Change of Time / Ida Jessen / Martin Aitken . 20 Message from the Shadows / Antonio Tabucchi / Elizabeth Harris, Martha Cooley and Antonio Romani, Janice M . Thresher, & Tim Parks . 22 My Name is Adam: Children of the Ghetto Volume One / Elias Khoury / Humphrey Davies . 24 elsewhere editions summer 2019 / fall 2020 frontlist The Gothamites / Eno Raud / Priit Pärn / Adam Cullen . 28 Seraphin / Philippe Fix / Donald Nicholson-Smith . 30 Charcoal Boys / Roger Mello / Daniel Hahn . 32 I Wish / Toon Tellegen / Ingrid Godon / David Colmer . 34 recently published . 39 backlist . 47 forthcoming . 88 how to subscribe . 92 how to donate . 92 distribution . 92 donors . 94 board of directors, advisory board, & staff . 96 What’s notable is Karl Ove’s ability . to be fully present in and mindful of his own existence . there. shouldn’t be anything remarkable about any of it except for the fact that it immerses you totally . You live his life with him . —Zadie Smith, The New York Review of Books How wonderful to read an experimental novel that fires every nerve ending while summoning . -

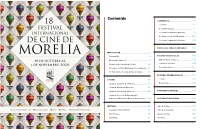

Contenido COMPETENCIA

Contenido COMPETENCIA ....................................................................... 45 El Premio ................................................................................ 46 Sección Michoacana ......................................................... 46 Sección de Cortometraje Mexicano ......................... 58 Sección de Documental Mexicano .........................119 Sección de Largometraje Mexicano .....................129 FORO DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS ................138 INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................4 PROGRAMAS ESPECIALES .......................................141 Presentación ...........................................................................................5 Gilberto Martínez Solares .........................................142 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ....................................................................7 Semana de la Crítica .....................................................149 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura .................................... 10 Festival de Cannes .........................................................164 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía ...... 11 18° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ���������������� 12 ESTRENOS INTERNACIONALES ...........................166 Ficción ...................................................................................167 JURADOS .................................................................................................. 14 Documentales -

Leonora Carrington. Metamorfosis Hacia La Autenticidad

Leonora Carrington. Metamorfosis hacia la autenticidad Leonora Carrington. Metamorphosis towards authenticity Leonora Carrington. Metamorphosis para a autenticidade Eduardo de la Fuente Rocha Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, México [email protected] Resumen Este trabajo es continuación del artículo "Leonora Carrington. Frente a la desestructuración". En el presente escrito se aborda la estancia que tuvo la artista en el Sanatorio Santander. Se compara el evento psicótico de Leonora Carrington con el de Daniel Paul Schreber, ambos narrados por los propios sujetos que lo experimentaron. La finalidad de hacer dicha comparación es analizar las diferencias que hay entre el evento de Schreber y el de Leonora, para entender por qué ella sí logró salir y él no. Posteriormente, desde del apartado llamado México, se realizó un análisis psicológico de la artista a través de su obra y la evolución de la misma, donde muestra su proceso de individuación entre los años 1942 y 2011. Para revisar el análisis de su psiquismo se han tomado dos fuentes: la biográfica y la autobiográfica. A través de este análisis puede observarse la evolución psíquica que la artista logró, lo que permite un mejor entendimiento del legado que su trabajo dejó a la humanidad. Palabras clave: sanatorio, Schreber, psicosis, psicología, Leonora Carrington. Abstract This work follows the article "Leonora Carrington, Facing the Destruction". The present paper approaches the subject about the stay that the artist had in the Santander Sanatorium. It compares the psychotic event of Leonora Carrington with the one of Daniel Paul Schreber, both narrated by the subjects who experienced it. The purpose of making the difference Vol. -

Worldwide Reading on September 5Th, 2021

for the dead © IMAGO/Xinhua of the pandemic Worldwide Reading on September 5th, 2021 Signatories of the Appeal: The international literature festival berlin [ilb] calls on individuals, ARGENTINA EDGARDO COZARINSKY I ALBERTO MANGUEL I POLA OLOIXARAC I PATRICIO PRON I EDUARDO SGUIGLIA schools, universities, cultural institutions and media to participate AUSTRALIA JOHN MATEER I CHARLOTTE WOOD AUSTRIA MARTIN AMANSHAUSER I DIETLIND ANTRETTER BELGIUM WILLEM in a Worldwide Reading for the Dead of the Corona Pandemic on M. ROGGEMAN BOSNIA-HERZEGOVINA NAIDA MUJKIC I STIPE ODAK I MIRZA OKIC I PEN INTERNATIONAL – BOSNIAN- September 5, 2021. The reading is intended to commemorate those HERZEGOVINA CENTRE BRAZIL RICARDO AZEVEDO I J. P. CUENCA I MILTON HATOUM BULGARIA GEORGI GOSPODINOV CANADA who died in the pandemic. RÉMY BÉLANGER DE BEAUPORT I LAURA DOYLE PÉAN I NATALIE FONTALVO I VALÉRIE FORGUES I GREG GATENBY I JONATHAN HUARD I IAIN LAWRENCE I MAISON DE LA LITTÉRATURE QUÉBEC I SHAYNE MICHAEL I SYLVIE NICOLAS I FRANCIS PARADIS ET For more than a year, the world has been in the grip of the pandemic. JUDY QUINN CHILE CARMEN BERENGUER I CARLOS LABBÉ CHINA LIAO YIWU I TIENCHI LIAO-MARTIN COLOMBIA JUAN CARLOS Nearly three million people worldwide have died from Covid-19. CÉSPEDES I LAURA RESTREPO CROATIA IVANA SAJKO CUBA NANCY MOREJÓN CZECH REPUBLIC RADKA DENEMARKOVÁ Not a day goes by when we are not confronted with statistics and DENMARK JONAS EIKA I PIA TAFDRUP DOMENICAN REPUBLIC LUISA A. VICIOSO SÁNCHEZ FRANCE JULIA BILLET I SHUMONA curves on current deaths and illnesses. Yet, it often remains abstract SINHA I STEFAN LUDMILLA WIESZNER GERMANY GABRIELE VON ARNIM I MATT AUFDERHORST I CARMEN-FRANCESCA BANCIU numbers. -

Endorsers of the Open Letter to Presidents Biden and Putin

Endorsers of the Open Letter to Presidents Biden and Putin Political, military and religious leaders, legislators, academics/scientists and other representatives of civil society* POLITICAL LEADERS & INFLUENCERS: Nobuyasu Abe, Japan Dr Irina Ghaplanyan, Armenia. Senior Adviser, Council on Strategic Risks. Former United Senior Advisor on Climate Change to the World Bank Group. Nations Under-Secretary-General for Disarmament Affairs; Former Deputy Minister of Environment; Ambassador Edy Korthals Altes, The Netherlands. Dame Jane Goodall, PhD, DBE, United Kingdom Former Ambassador of The Netherlands to Spain and Primatologist, Founder of the Jane Goodall Institute. President of the World Conference of Religions for Peace; UN Messenger for Peace. Honorary Member of the World Future Council; Lord (Des) Browne of Ladyton, United Kingdom. Member of UK House of Lords. Former Defence Secretary. Ambassador (ret) Thomas Graham Jr. USA Chair, European Leadership Network; Former Special Representative of the President for Arms Control, Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Ambassador Libran Nuevas Cabactulan, Philippines Former Permanent Representative of the Philippines to the Dr Anatoliy Grytsenko, Ukraine. United Nations in New York. President of the 2010 NPT Former Defense Minister (2005-2007); Head, National Review Conference. Security & Defense Committee of Parliament; Vincenzo Camporini, Italy. Lord David Hannay of Chiswick, United Kingdom. Scientific Advisor at Istituto Affari Internazionali. Crossbench Peer, UK House of Lords. Co-Chair of the UK All Former Minister of Defence. Party Parliamentary Group on Global Security and Non- proliferation. Senior Member, European Leadership Network. Ingvar Carlsson, Sweden. Former Prime Minister of Sweden. Silvia Hernández, México Senior Member, European Leadership Network; Founding Partner of Estrategia Pública Consultores. -

The Child Poet Online

6Dm7y [Download free ebook] The Child Poet Online [6Dm7y.ebook] The Child Poet Pdf Free Homero Aridjis ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook #1429759 in Books 2016-02-23 2016-02-23Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 6.50 x .50 x 5.60l, .81 #File Name: 0914671405153 pages | File size: 42.Mb Homero Aridjis : The Child Poet before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised The Child Poet: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Poetry as memoirBy TroubleIn the introduction by Chloe Aridis, she explains that Aridjis told her that ldquo;Because all memory is relative, it was difficult to avoid modifying his memories. They are vulnerable to subsequent experience and of course to the language in which they are lived and acquired and later recorded.rdquo;I found this memoir to be poetry, perhaps not as it is narrowly understood. When in a gathering, Aridjis, spoke of the need to hide himself from view, to stay away from others, to avoid conversation. I loved this: ldquo;But when I couldnrsquo;t find the words to slip away, or a view to distract me, unmoved and subdued, I would summon up my forces to hide my boredom or my secret desire to slap that person in the face and depart.rdquo;This is story after story, person after person, one leading to the next, encapsulating a lifetime. One moment is understood by its proximity to the next; one person by its proximity to the next.I found this haunting and beautiful.(Pictures? There had to be pictures.)1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. -

Leonora Carrington Y El Juego Surrealista Leonora Carrington

LEONORA CARRINGTON Y EL JUEGO SURREALISTA LEONORA CARRINGTON. THE SURREALIST GAME Dirigido por/Directed by JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ Productora/Production Company: TIME ZONE, S.L. Tutor, 19. 6º Dcha. 28008 Madrid. Tel.: +34 915411122 / +34 629302932. www.timezoneproducciones.com ; [email protected] Director: JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ. Producción ejecutiva/Executive Producer: SONIA TERCERO RAMIRO. Dirección de producción/Line Producer: PAL BILBAO. Guión/Screenplay: JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ, SONIA TERCERO RAMIRO. Fotografía/Photography: ALEJANDRO ALCOCER, DIEGO CORTÉS. Música/Score: JUAN BARDEM, CARMEN YEPES MARTÍN. Montaje/Editing: VICTORIA OLIVER FARNER. Sonido/Sound: JESÚS FELIPE SANCHEZ. Intérpretes/Cast: LEONORA CARRINGTON, GABRIEL WEISZ, ELENA PONIATOWSKA, ALAN GLASS, CARLOS MONSIVAIS, LUIS CARLOS EMERICH, HERMANAS PECANINS, ISAAC MASRI. Largometraje/Feature Film. HD. Género/Genre: Biográfica / Biographical. Duración/Running time: 76 minutos. Fechas de rodaje/Shooting dates: 15/12/2011 - 14/01/2012. Lugares de rodaje/Locations: México D.F., Casa de América (Madrid), Museo Picasso (Málaga), Valdecilla (Cantabria). Festivales/Festivals: Web: www.timezoneproducciones.com ; l Festival de Málaga. Cine Español 2013 Documentales sesiones especiales www.facebook.com/timezoneproducciones l Festival Internacional de Cine de Guadalajara 2012, México Sección Panorama l Muestra de Cine Europeo de Segovia 2012 Cine documental l Sitges 2012 Festival Internacional de Cine Fantástico de Cataluña Noves Visions - No Ficció l II Encuentro Internacional de Documentales de Artes ARTES.DOCS 2012, México D.F. 2012 l FMDI 2012 Sección Arte Selección Oficial. Ventas internacionales/International Sales: TIME ZONE, S.L. Tutor, 19. 6º Dcha. 28008 Madrid. Tel.: +34 915411122 / +34 629302932. www.timezoneproducciones.com ; [email protected]. JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ/Filmografía/Filmography: Largometrajes/Feature films: l 2012 - LEONORA CARRINGTON Y EL JUEGO SURREALISTA La última superviviente del movimiento surrealista cuenta la odisea de una mujer por ser libre.