Studia Culturae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Telescope and Microscope

Telescope and Microscope Alberto Blanco* Private collection. © Estate of Leonora Carrington The Birdmen of Burnley, 45 x 65 cm (oil on canvas). midst the horror of World War II, in the entry dated Tuesday, August 24, 1943, of her extraordinary autobiographical tale, Down Below, Leonora Carrington made this surpris Aing statement: This last sentence, rightfully quoted often, speaks to us of an artist, a human being who did not settle for seeing only part of reality. To the contrary, Leonora Carrington, interested in the Big and the Small —that which in traditional symbolism is known as the Great Mysteries and the Small * Poet, translator, essayist, and visual artist; member of the National Sys tem of Creators of Art (SNCA), [email protected]. 50 Mysteries— never wanted to ignore the great scientific or philosophical themes. Throughout her long, intense life, she was just as interested in astronomy as in astrology, in quantum physics as in the mysteries of the psyche; and at the same time, she never turned her back on what could be considered the minutiae and the details of daily life: her family, her home, her beloved objects, her friends, her pets, her plants. © Estate of Leonora Carrington Private collection. In Leonora Carrington, a profoundly romantic artist —and here, I mean the great English romanticism, that of William Blake, for example— and an eminently practical person co existed without any contradiction. Also found together were a profound sense of humor —also very English, consisting frequently of talking very seriously about the most absurd topics— and the most serious determination to do work that never admitted of the slightest vacillation and suffered no foolishness at all. -

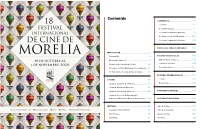

Contenido COMPETENCIA

Contenido COMPETENCIA ....................................................................... 45 El Premio ................................................................................ 46 Sección Michoacana ......................................................... 46 Sección de Cortometraje Mexicano ......................... 58 Sección de Documental Mexicano .........................119 Sección de Largometraje Mexicano .....................129 FORO DE LOS PUEBLOS INDÍGENAS ................138 INTRODUCCIÓN .......................................................................................4 PROGRAMAS ESPECIALES .......................................141 Presentación ...........................................................................................5 Gilberto Martínez Solares .........................................142 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ....................................................................7 Semana de la Crítica .....................................................149 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura .................................... 10 Festival de Cannes .........................................................164 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía ...... 11 18° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ���������������� 12 ESTRENOS INTERNACIONALES ...........................166 Ficción ...................................................................................167 JURADOS .................................................................................................. 14 Documentales -

Leonora Carrington. Metamorfosis Hacia La Autenticidad

Leonora Carrington. Metamorfosis hacia la autenticidad Leonora Carrington. Metamorphosis towards authenticity Leonora Carrington. Metamorphosis para a autenticidade Eduardo de la Fuente Rocha Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, México [email protected] Resumen Este trabajo es continuación del artículo "Leonora Carrington. Frente a la desestructuración". En el presente escrito se aborda la estancia que tuvo la artista en el Sanatorio Santander. Se compara el evento psicótico de Leonora Carrington con el de Daniel Paul Schreber, ambos narrados por los propios sujetos que lo experimentaron. La finalidad de hacer dicha comparación es analizar las diferencias que hay entre el evento de Schreber y el de Leonora, para entender por qué ella sí logró salir y él no. Posteriormente, desde del apartado llamado México, se realizó un análisis psicológico de la artista a través de su obra y la evolución de la misma, donde muestra su proceso de individuación entre los años 1942 y 2011. Para revisar el análisis de su psiquismo se han tomado dos fuentes: la biográfica y la autobiográfica. A través de este análisis puede observarse la evolución psíquica que la artista logró, lo que permite un mejor entendimiento del legado que su trabajo dejó a la humanidad. Palabras clave: sanatorio, Schreber, psicosis, psicología, Leonora Carrington. Abstract This work follows the article "Leonora Carrington, Facing the Destruction". The present paper approaches the subject about the stay that the artist had in the Santander Sanatorium. It compares the psychotic event of Leonora Carrington with the one of Daniel Paul Schreber, both narrated by the subjects who experienced it. The purpose of making the difference Vol. -

Leonora Carrington Y El Juego Surrealista Leonora Carrington

LEONORA CARRINGTON Y EL JUEGO SURREALISTA LEONORA CARRINGTON. THE SURREALIST GAME Dirigido por/Directed by JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ Productora/Production Company: TIME ZONE, S.L. Tutor, 19. 6º Dcha. 28008 Madrid. Tel.: +34 915411122 / +34 629302932. www.timezoneproducciones.com ; [email protected] Director: JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ. Producción ejecutiva/Executive Producer: SONIA TERCERO RAMIRO. Dirección de producción/Line Producer: PAL BILBAO. Guión/Screenplay: JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ, SONIA TERCERO RAMIRO. Fotografía/Photography: ALEJANDRO ALCOCER, DIEGO CORTÉS. Música/Score: JUAN BARDEM, CARMEN YEPES MARTÍN. Montaje/Editing: VICTORIA OLIVER FARNER. Sonido/Sound: JESÚS FELIPE SANCHEZ. Intérpretes/Cast: LEONORA CARRINGTON, GABRIEL WEISZ, ELENA PONIATOWSKA, ALAN GLASS, CARLOS MONSIVAIS, LUIS CARLOS EMERICH, HERMANAS PECANINS, ISAAC MASRI. Largometraje/Feature Film. HD. Género/Genre: Biográfica / Biographical. Duración/Running time: 76 minutos. Fechas de rodaje/Shooting dates: 15/12/2011 - 14/01/2012. Lugares de rodaje/Locations: México D.F., Casa de América (Madrid), Museo Picasso (Málaga), Valdecilla (Cantabria). Festivales/Festivals: Web: www.timezoneproducciones.com ; l Festival de Málaga. Cine Español 2013 Documentales sesiones especiales www.facebook.com/timezoneproducciones l Festival Internacional de Cine de Guadalajara 2012, México Sección Panorama l Muestra de Cine Europeo de Segovia 2012 Cine documental l Sitges 2012 Festival Internacional de Cine Fantástico de Cataluña Noves Visions - No Ficció l II Encuentro Internacional de Documentales de Artes ARTES.DOCS 2012, México D.F. 2012 l FMDI 2012 Sección Arte Selección Oficial. Ventas internacionales/International Sales: TIME ZONE, S.L. Tutor, 19. 6º Dcha. 28008 Madrid. Tel.: +34 915411122 / +34 629302932. www.timezoneproducciones.com ; [email protected]. JAVIER MARTÍN-DOMÍNGUEZ/Filmografía/Filmography: Largometrajes/Feature films: l 2012 - LEONORA CARRINGTON Y EL JUEGO SURREALISTA La última superviviente del movimiento surrealista cuenta la odisea de una mujer por ser libre. -

Leonora Carrington and the International Avant-Garde Jonathan P

Introduction Leonora Carrington and the international avant-garde Jonathan P. Eburne and Catriona McAra Over the course of her extensive artistic and literary career, Leonora Carrington (1917–2011) took part in numerous interviews. While generally amenable to discussing her life and work, she patently refused to explain it. A late interview with the curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist provides a striking, almost comic example of her resistance to answering questions about the origins and infl uences of her art. ‘Can you tell us more about the recurrence of horses?’ he asks. ‘I can,’ she replies, trotting out a formulaic and self-cancelling reply. ‘I used to ride a lot. My mother was Irish and it is well known that the Irish have a tradition with horses. This is a logical reply and I don ’ t think it ’ s really true. I don ’ t think it is that simple, but I don ’ t really know.’ 1 The interviewer ’ s attempt to locate a subjective origin for Carrington ’ s artistic themes and motifs swiftly arrives at a dead end. Her self- cancelling response is nonetheless revealing. In the negation of simple explanation, that is, we learn something of Carrington ’ s artistic process: not the ‘meaning’ of individual works or motifs, but the experimental form and force of her long career as an artist. Carrington ’ s career is marked by an experimentation rooted in diffi - culty, mystery, and the openness to uncertainty and non-knowledge, a commit- ment she articulates at the very moment she seems most obdurately to be fl outing the terms of the interview: ‘I don ’ t think it is that simple, but I don ’ t really know.’ Carrington ’ s resistance to interrogation is far from curmudgeonly. -

Mexican Autobiography an Essay and Annotated Bibliography

750 HISPANIA 77 DECEMBER 1994 Mexican Autobiography: An Essay and Annotated Bibliography Richard D. Woods Trinity University Abstract: The introductory essay traces tendencies in Mexican autobiography and outlines a variety of subgenres, focusing mainly on lifewritings since 1980. The annotated bibliography complements the author's previous bibliography of the genre up to 1980, since continuums and contrasts of the two large periods, 1492- 1979 and 1980-1993, illuminate the characteristics of this neglected genre. The bibliography of 347 entries denotes a growing field of endeavor in Mexican writing that is in need of critical attention and recognition. Key Words: autobiographical novel, autobiography proper, bibliography, diaries, journals, letters, memoirs, Mexican Americans, Mexico, oral autobiography, testimony, women's writing Mexican autobiography exists. It In spite of the large number of autobiog- may seem strange, but the fact raphies noted, the genre has received little that the substantial body of recognition from Mexican scholars and spo- lifewritings in that country has simply not radic attention in the U.S. An exception, received attention makes such a declaration Sylvia Molloy's At Face Value.- Autobio- necessary. While the Mexican novel, short graphical Writing in Spanish America story, drama, poetry and essay find an easy (1991), signals the scholarly world to some forum, this is not true for autobiography. classical examples, but since the book cov- Without broaching all the possible reasons ers a wide geographical area, the focus on for the neglect, one might venture to say Mexico is understandably limited to its best that the disregarding of a form so pervasive known autobiographer, Jose Vasconcelos. -

I PAINT MY REALITY Surrealism in Latin America Through Spring 2021

I PAINT MY REALITY Surrealism in Latin America Through Spring 2021 The avant-garde Surrealist movement emerged in France in the wake of World War I and spread globally as artists and art works traveled, and ideas circulated through art journals and mass media. Dreams, psychoanalysis, automatism (creating without conscious thought), collage, assemblage and chance were among the methods the Surrealists used to tap into the unconscious mind and stimulate the imagination. The European Surrealists embraced their Latin American colleagues, who nevertheless expressed ambivalence about the movement. Mexican artist Frida Kahlo famously refuted being labeled as a Surrealist, stating that she never painted dreams, instead asserting, “I painted my own reality,” while Uruguayan Joaquin Torres-Garcia advocated for a modern art that was not beholden to European modern art. Latin America’s complex history, magical landscapes, indigenous cultures, archeological sites, mythologies, migrations, and European and African religious traditions shaped these artists’ reality. The rise of fascism in Europe in the 1930s as well as the Spanish Civil War and World War II shifted the focus of Surrealism to the United States and Latin America, where many of the European artists sought refuge. These artists’ proximity to each other promoted friendships that were especially fruitful during this period and in the post-war years. While many of the exiled European artists who lived in the United States during the war returned home afterwards, those in Latin America and in Mexico in particular, tended to remain there for the rest of their lives. This exhibition is drawn exclusively from NSU Art Museum’s Latin American collection, including promised gifts from Fort Lauderdale collectors Stanley and Pearl Goodman. -

8433 Surrealist Ireland

Word Count: 8433 Surrealist Ireland: the Archaic, the Modern and the Marvellous Fionna Barber A Companion to Modern Art ed. Pam Meecham, Wiley-Blackwell 2016 Abstract: This essay has a dual focus: the representation of Ireland in Surrealism and the significance of Surrealism for Irish artists. The redrawn Surrealist map of the world (1929) gave Ireland a prominent position while Irish writers such as Swift and Synge played an important role in the formation of Surrealist ideas of the marvellous from an early stage. The disjuncture of notions of the archaic and the modern also informed the ways that Irish artists engaged with Surrealist strategies in their work. Relationships between the marvellous, the archaic, the modern and notions of femininity are examined in the work of Colin Middleton and Leonora Carrington mid twentieth century, and in the more recent practice of Alice Maher. A restaged Surrealist inquiry by Gerard Byrne also problematizes relationships of archaic and modern with relevance for gender politics in Ireland. Keywords Surrealism, Ireland, Antonin Artaud, Colin Middleton, Leonora Carrington, Alice Maher, Gerard Byrne, archaic, modern, marvellous 1 In 1929 the Belgian journal Varietés published a map of the world remade from a Surrealist perspective. The different countries of Western Europe have been replaced in significance by the islands of Polynesia, while the great bulk of Alaska dominates North America where the remainder of the United States used to be. Ireland is prominently included, floating off the coast of Europe and looming over the tiny blob that represents Britain. France, Britain’s fellow imperial power, has disappeared completely, while Paris is now attached to the distorted remainder of Europe. -

Espacio, Emoción Y Poesía: Ritmo Urbano Y Versificación En La Ciudad De México (1888‐1945)

ESPACIO, EMOCIÓN Y POESÍA: RITMO URBANO Y VERSIFICACIÓN EN LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO (1888‐1945) Tesis que para optar al grado de Doctor en Literatura Hispánica presenta JUAN LEYVA Asesor: Dr. ANTHONY STANTON EL COLEGIO DE MÉXICO México, D. F., febrero de 2009 3 ÍNDICE Dedicatoria_________________________________________________________________________ 5 Agradecimientos_____________________________________________________________________ 7 Resumen____________________________________________________________________________ 9 INTRODUCCIÓN__________________________________________________________________ 11 Forma urbana, movimiento y forma de la subjetividad_____________________________ 23 ‐La interacción recursiva entre espacio y sociedad_________________________ 26 ‐Interior y exterior, presencia y ausencia: la espacialidad del ritmo___________30 -La calle y la forma global del espacio urbano_____________________________35 Ciudad y representación_____________________________________________________ 40 ‐La poesía y la voz de la experiencia: una representación emotiva del espacio__ 48 Algunas delimitaciones______________________________________________________ 53 ESTADO DE LA CUESTIÓN_________________________________________________________ 61 Panorama general___________________________________________________________62 Collot, Williams y Dessons: una ruta entre el espacio, la experiencia y el poema_________ 68 Lecciones y omisiones de Benjamin_____________________________________________ 82 ‐Poética y representación en Baudelaire__________________________________ -

La Escena Del Crimen

Reservados todos los derechos. Ninguna parte de esta publicación puede ser reproducida, almacenada o transmitida de ninguna forma, ni por ningún medio, sea este electrónico, fotocopia o cualquier otro, sin la previa autorización escrita por el autor. La escena del crimen. Crimen y suspenso en el cine mexicano, 1946-1955. Tesis para optar al grado de Doctor en Ciencias Humanas con Especialidad en Estudio de las Tradiciones Que presenta Alvaro A. Fernández Reyes Comité de Tesis Director: Dr. Miguel J. Hernández Madrid (CER-Colmich) Lectora: Dra. Norma Iglesias Prieto (San Diego State University) Lector: Dr. Ramón Gil Olivo (CIEC- U de G) EL COLEGIO DE MICOACAN, A.C. CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE LAS TRADICIONES Zamora, Michoacán, México Diciembre de 2005 2 Agradecimientos A Olimpia y a mis demás cómplices (que no delataré) en esta historia de crimen y suspenso... Índice Introducción........................................................................................................................... 6 1. Escenarios culturales 1.1 La modernización del país o la paradoja del milagro mexicano..............................33 1.2 La ciudad de México: una quimera urbana............................................................. 38 1.2.1 El barrio y vecindades: arrojo de una cultura urbana popular..............41 1.2.2 La ciudad al servicio de los demás......................................................44 1.3 Nuevas costumbres de consumo cultural en la vida cotidiana............................... 45 1.3.1 La reinvención del nacionalismo cultural............................................ -

Reading Elena Poniatowska's Leonora in an Undergraduate Seminar

Diálogo Volume 17 Number 1 Article 4 2014 Reading Elena Poniatowska's Leonora in an Undergraduate Seminar Aurora Camacho de Schmidt Swarthmore College Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo Part of the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Camacho de Schmidt, Aurora (2014) "Reading Elena Poniatowska's Leonora in an Undergraduate Seminar," Diálogo: Vol. 17 : No. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/dialogo/vol17/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Latino Research at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Diálogo by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reading Elena Poniatowska's Leonora in an Undergraduate Seminar Aurora Camacho de Schmidt Swarthmore College I live to the rhythm of my country and I cannot remain on the sidelines. I want to be there. I want to be part of it. I want to be a witness. I want to walk arm in arm with it. I want to hear it more and more, to cradle it, to carry it like a medal on my chest. Elena Poniatowska1 members. I have found no full critical treatments in Abstract: Description of an Honors literature seminar academic journals of this most recent novel written by focused on a selection of texts by prominent Mexican Poniatowska, but some reviews are extremely helpful.3 writer Elena Poniatowska, including critical strategies While the French translation was published in September involved in preparation, work required by students, and of 2012, an English one is not yet available.4 Poniatowska’s creative strategies in depicting rebellious women and other socially marginalized figures. -

Friday 25 Lifestyle | Feature Friday, May 28, 2021

Friday 25 Lifestyle | Feature Friday, May 28, 2021 View inside British-Mexican artist Leonora Carrington’s (1917-2011) house and studio in Mexico City. A sculpture by British-Mexican artist Leonora Carrington (1917- View of letters received by British-Mexican artist Leonora View of sculptures and plants inside British-Mexican artist Leonora 2011) called ‘Night Jaguar’ is seen at her house and studio in Carrington (1917-2011) at her house and studio in Mexico City. Carrington’s (1917-2011) house and studio in Mexico city. Mexico City. In exchange, on May 19 he donated works of his mother began a love affair with painter Max Ernst. valued at three million dollars. The museum in Colonia After Ernst was arrested by the Gestapo in Nazi-occupied Roma houses 45 sculptures and hundreds of objects that France, Carrington fell into a deep depression before being Carrington used while living there, including her food sea- committed to a psychiatric hospital in Spain. She managed sonings and makeup. The intention is “to preserve the inti- to escape, and in Lisbon married the Mexican poet and jour- mate character of the dining room, bedroom, kitchen and nalist Renato Leduc, who in 1942 took her to Mexico. She study with the idea of presenting them as closely as they settled there permanently, befriending painter Frida Kahlo were in the artist’s daily life,” Osorio said. The opening date and future Nobel laureate Octavio Paz. Carrington died in will depend on the evolution of the coronavirus pandemic in May 2011 in Mexico City at the age of 94.—AFP Mexico, she added.