I PAINT MY REALITY Surrealism in Latin America Through Spring 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspects of Suburban Life- Main Street, 1937, Paul Cadmus, Loan, G360 Dunlap, Sept

Aspects of Suburban Life: Main Street, 1937, Paul Cadmus, Curtis Galleries Loan, G360 Questions Questions 1. What’s going on in this painting? ! 2. What could be some reasons for titling this “Suburban Life”? ! 3. What could be a reason for the expression on the face of the woman dressed in black? ! 4. In 1936 Cadmus was commissioned by TRAP (later WPA) to design 4 murals for the post office (or library) in affluent Port Washington (some considered the model for Fitzgerald’s town in The Great Gatsby). His paintings, however, were rejected as inappropriate. Considering the hardships and sacrifices of the Depression, why might this have been objectionable? ! Main Points 1. The 2 girls, along with their friend, dominate the canvas and the street scene. Two carry tennis racquets. The girl closest to us resists the pull of her dachshund on a long red leash. They draw the leers or stares of disapproval from many on the street except, perhaps, the policeman who seems to halt traffic just for them to cross. 2. Small town buildings such as the Woolworth’s, the drugstore, the one with a false-front, the theater, the church spire, all proclaim Main Street, USA. Cars, not streetcars, are the preferred means of transportation as small towns become commuter communities. 3. The tennis trio seems careless and self-satisfied; their goal is to enjoy the country club life in the depths of the Depression. The commuter community is displacing/shoving aside the town’s longstanding residents. 4. The lounging “local yokels” watching the passing scene, the auto repair in progress, the contrast between the idle, complacent nouveau riche and the rest of the town, the chaotic scene -- all cast a less than ideal view of the town. -

The Painting of Modern Life: Paris in the Art of Maner and His Followers / T

THE PAINTING of Copyright © 1984 by T. f. Clark All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published by Princeton University.Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540. Reprinted by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. MODERN LIFE Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously pub- lished material: Excerpt from "Marie Lloyd" in Selected Essays by T. S. Eliot, copyright 1950 by Harcourt Brace [ovanovich, Inc.; renewed ]978 by Esme Valerie Eliot. Reprinted by permission PARISIN THE ART OF MANET AND HIS FOLLOWERS of the publisher. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUnUCATION DATA Revised Edition Clark, T. J. (Timothy J.) The painting of modern life: Paris in the art of Maner and his followers / T. 1- Clark. - Rev. ed. P: em. Includes bibliographica! references and index. T.1.CLARK ISBN 0-69!-00903-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Impressionism (Art)-France-Paris. 2. Painting, French- France-Paris. 3. Painting, Modern-19th century+=France-c-Paris. 4. Paris (Francej-c-In art. 5. Maner, Edouard, l832-1883--Inftuencc, I. Title. ND550.C55 1999 758'.9944361-dc21 99-29643 FIRST PRINTING OF THE REVISED EDITION, 1999 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA FIRST PRINCETON PAPERBACK PRINTING, 1986 THIRD PRINCETON PAPERBACK PRINTING, 1989 9 8 7 CHAPTER TWO OLYMPIA'S CHOICE "We shall define as prostitute only that woman who, publicly and without love, gives herself to the first comer for a pecuniary remuneration; to which formula we shall add: and has no other means of existence besides the temporary relations she entertains with a more or less large number of individuals." From which itfollows--and it seems to me the truth--that prostitute implies first venality and second absence of choice. -

Una Mirada a La Inmigración Española De 1939-40 En Santo Domingo

Una mirada a la inmigración española de 1939-40 en Santo Domingo Disertaciones presentadas en la Universidad APEC Semanas de España en la República Dominicana 2015 Santo Domingo, R.D. Octubre 2016 Una mirada a la inmigración española de 1939-40 en Santo Domingo : disertaciones presentadas en la Universidad APEC : Semanas de España en la República Dominicana 2015 / José del Castillo Pichardo ...[et al.] ; Jaime Lacadena, introducción. – Santo Domingo : Universidad APEC, 2016 168 p. : il. ISBN: 978-9945-423-39-6 1. Emigración - Española 2. Inmigración - República Dominicana 2. España - Historia - Guerra civil, 1936-1939 3. Exilio - España 4. República Dominicana - Influencias españolas 3. Arte dominicano - Influencias españolas 5. España - Vida intelectual - República Dominicana. I. Castillo Pichardo, José del. II. González Tejera, Natalia. III. Vega, Bernardo. IV. Gil Fiallo, Laura. V. Mateo, Andrés L. VI. Céspedes, Diógenes. VII. Lacadena, Jaime, introd. 304.8 I57e CE/UNAPEC Título de la obra: Una mirada a la inmigración española de 1939-40 en Santo Domingo Disertaciones presentadas en la Universidad APEC Semanas de España en la República Dominicana 2015 Primera edición: Octubre 2016 Gestión editorial: Oficina de Publicaciones Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Innovación y Relaciones Internacionales Composición, diagramación y diseño de cubierta: Departamento de Comunicación y Mercadeo Institucional Impresión: Editora Búho ISBN: 978-9945-423-39-6 Impreso en República Dominicana Printed in Dominican Republic JUNTA DE DIRECTORES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD APEC Lic. Opinio Álvarez Betancourt Presidente Lic. Fernando Langa Ferreira Vicepresidente Lic. Pilar Haché Tesorera Dra. Cristina Aguiar Secretaria Lic. Álvaro Sousa Sevilla Miembro Lic. Peter A. Croes Miembro Lic. Isabel Morillo Miembro Lic. -

Artist Archaeologist Gonzalo Fonseca ARTIST ARCHAEOLOGIST GONZALO FONSECA (1922-1997)

PUBLIC ART EXPLORER Artist Archaeologist Gonzalo Fonseca ARTIST ARCHAEOLOGIST GONZALO FONSECA (1922-1997) Sun Boat North Shore Drive Pylon 1965 Underpass 1965 Concrete 1965 Concrete N S D Map #1 Concrete Map #3 Map #2 B Trail N S D B Trail M D Gr Trail W P W M D 3 2 1 Gr Trail N S D S N 2 H C LEARN Who was Gonzalo Fonseca? A Budding Artist He was born and raised in Uruguay in South America. When he was eleven, Fonseca spent six months traveling in Europe with his family. The things he experienced and saw on this trip inspired him to become an artist. When his family returned home he set up an art studio in the basement. A Curious Mind Fonseca was a very curious person. He loved learning about history and languages (he spoke at least six!). Fonseca is often called a polymath*, or someone who knows a lot about many different things. He also traveled to continue his education. On his journeys, Fonseca climbed pyramids in Egypt, helped excavate ancient sites in the Middle East and Africa, and visited ancient Greek and Roman ruins. All of these experiences became a part of his artwork. An Inventive Sculptor Fonseca trained to be a painter but switched to sculpture because he wanted to work in three dimensions. The Lake Anne play sculptures are some of the only public art he ever made. They are molded from the same concrete used in the surrounding buildings. Fonseca was excited to have such big spaces to work with, places like the plaza by the lake and the underpass. -

La Colaboración De Kati Horna Con La Revista S.Nob Power to Imagination: Kati Horna’S Collaboration with S.Nob Magazine

GIULIA DEGANO PODER A LA IMAGINACIÓN: LA COLABORACIÓN NOB S. DE KATI HORNA CON LA REVISTA S.NOB POWER TO IMAGINATION: KATI HORNA’S EVISTA COLLABORATION WITH MAGAZINE R S.NOB A L ON C Resumen Abstract El presente trabajo pretende resaltar una pe- this paper aims to highlight essential as a queña en cuanto imprescindible parte de la small part of the extensive production of ORNA amplia producción de la fotógrafa Kati Horna photographer Kati Horna (1912-2000), mainly H (1912-2000), es decir las tres series mexica- the three series made for Mexican magazine nas realizadas para la revista S.nob en 1962, o S.nob in 1962, or Oda a la Necrofilia, Impromptu ATI Oda a la Necrofilia, Impromptu con Arpa con Arpa Paraísos artificiales. K bien and the text E y Paraísos artificiales. El texto propone un aná- proposes an analysis of both series as well as D lisis tanto de dichas series así como de algunas some contemporary emblematic works to those obras emblemáticas contemporáneas a dichos reportages. reportajes. Palabras Clave Key Words Exilio, Fotografía, guerra Civil Española, Exile, Photography, spanish Civil War, México, Surrealism OLABORACIÓN México, Surrealismo 66 C A : L giulia Degano Università degli studi di Udine Dipartimento di storia e tutela dei Beni Culturali Polo umanistico e della formazione MAGINACIÓN I Udine A Es Maestra en Historia del Arte y Conserva- A L ción de los Bienes artísticos y arquitectónicos por la Università degli studi di Udine. En 2013 cursó parte de su maestría en la Universidad ODER P Iberoamericana de la Ciudad de México, donde colaboró, además, con el Laboratorio de Con- servación Preventiva del Museo de antropolo- gía. -

Fotografías De Ruth Lechuga

¿QUÉ HACER EN OTROS MUSEOS? El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes será el anfitrión de la exposición Olga Costa. OLGA COSTA. APUNTES DE Apuntes de la Naturaleza 1913-2013 hasta el 27 de octubre de este año. Olga Kostakowsky Fabricant, mejor conocida como Olga Costa, nacida en Leipzing, Alemania en 1913, llegó a México y se estableció en la Ciudad de México a los 12 LA NATURALEZA 1913-2013 años. Aquí conoció a Diego Rivera, Rufino Tamayo y Frida Kahlo. Inspirada por los grandes maestros, estudió en la Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas. En 1935, fecha de su matrimonio con José Chávez Morado, se mudó al estado de Guanajuato, donde regresó al mundo de la pintura para presentar su primera exposición en 1944 en la Galería de Arte Mexicano. Durante su vida artística formó • parte de la galería Espiral y recibió el Premio Nacional de Ciencias y Artes en 1990. » SUSANA RIVAS El Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes reúne 75 piezas de la artista con motivo del centenario de su nacimiento, bajo la curaduría de Juan Rafael Coronel. Durante el recorrido en salas, se pueden apreciar los temas recurrentes en las pinturas de Olga Costa, como retratos, autorretratos, paisajes, además la influencia que tuvieron sobre sus obras corrientes como la escuela al aire libre, el cubismo y el fauvismo, entre otras. Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes Av. Juárez y Eje Central s/n, Centro Histórico Martes a domingo, 10 a 17:30 h. 43 pesos Olga Costa, Hombre desnudo, Domingo entrada libre 1937, Colección particular 5512-2593 REMEDIOS VARO. -

LATIN AMERICAN and CARIBBEAN MODERN and CONTEMPORARY ART a Guide for Educators

LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ART A Guide for Educators The Teacher Information Center at The Museum of Modern Art TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. A NOTE TO EDUCATORS IFC 2. USING THE EDUCATORS GUIDE 3. ARTISTS AND ARTWORKS 42. THEMATIC APPROACHES TO THE ARTWORKS 48. SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND RESOURCES 52. MoMA SCHOOL PROGRAMS No part of these materials may be reproduced or published in any form without prior written consent of The Museum of Modern Art. Design © 2004 The Museum of Modern Art, New York Available in English and Spanish from the Teacher Information Center at The Museum of Modern Art. A NOTE TO EDUCATORS We are delighted to present this new educators guide featuring twenty artworks by 1 Latin American and Caribbean artists. The guide was written on the occasion of MoMA at A El Museo: Latin American and Caribbean Art from the Collection of The Museum of Modern N O Art, a collaborative exhibition between MoMA and El Museo del Barrio. The show, which T E runs from March 4 through July 25, 2004, celebrates important examples of Latin T O American and Caribbean art from MoMA’s holdings, reflecting upon the Museum’s collec- E D tion practices in that region as they have changed over time, as well as the artworks’ place U C A in the history of modernism. T O The works discussed here were created by artists from culturally, socioeconomically, R politically, and geographically diverse backgrounds. Because of this diversity we believe S that educators will discover multiple approaches to using the guide, as well as various cur- ricular connections. -

Morton Subastas SA De CV

Morton Subastas SA de CV Lot 1 CARLOS MÉRIDA Lot 3 RUFINO TAMAYO (Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, 1891 - Ciudad de México, 1984) (Oaxaca de Juárez, México, 1899 - Ciudad de México, 1991)< La casa dorada, 1979 Mujer con sandía, 1950 Firmada a lápiz y en plancha Firmada Mixografía 97 / 100 Litografía LIX / LX Procedencia: Galería del Círculo. Publicada en: PEREDA, Juan Carlos, et al. Rufino Tamayo Catalogue Con documento de la Galería AG. Raisonné Gráfica / Prints 1925-1991, Número 32. México. Fundación Olga y "Un hombre brillante que se daba el lujo de jugar integrando todos los Rufino Tamayo, CONACULTA, INBA, Turner, 2004, Pág. 66, catalogada 32. elementos que conocía, siempre con una pauta: su amor a lo indígena que le dio Impresa en Guilde Internationale de l'Amateur de Gravures, París. su razón de ser, a través de una geometría. basado en la mitología, en el Popol 54.6 x 42.5 cm Vuh, el Chilam Balam, los textiles, etc. Trató de escaparse un tiempo (los treintas), pero regresó". Miriam Kaiser. $65,000-75,000 Carlos Mérida tuvo el don de la estilización. Su manera de realizarlo se acuñó en París en los tiempos en que se cocinaban el cubismo y la abstracción. Estuvo cerca de Amadeo Modigliani, el maestro de la estilización sutil, y de las imágenes del paraíso de Gauguin. Al regresar a Guatemala por la primera guerra mundial decide no abandonar el discurso estético adopado en Europa y más bien lo fusiona con el contexto latinoamericano. "Ningún signo de movimiento organizado existía entonces en nuestra América", escribe Mérida acerca del ambiente artístico que imperaba a su llegada a México en 1919. -

Cartelera Cultural Octubre 2011

CARTELERA CULTURAL OCTUBRE 2011 OFICIALÍA MAYOR Dirección General de Promoción Cultural, Obra Pública y Acervo Patrimonial SECRETARÍA DE HACIENDA Y CRÉDITO PÚBLICO Ernesto Cordero Arroyo Secretario de Hacienda y Crédito Público Luis Miguel Montaño Reyes Oficial Mayor José Ramón San Cristóbal Larrea Director General de Promoción Cultural, Obra Pública y Acervo Patrimonial José Félix Ayala de la Torre Director de Acervo Patrimonial Fausto Pretelin Muñoz de Cote Director de Área Edgar Eduardo Espejel Pérez Subdirector de Promoción Cultural Rafael Alfonso Pérez y Pérez Subdirector del Museo de Arte de la SHCP Juan Manuel Herrera Huerta Subdirector de Bibliotecas María de los Ángeles Sobrino Figueroa Subdirectora de Control de Colecciones Museo de Arte de la SHCP Antiguo Palacio del Arzobispado www.hacienda.gob.mx/museo Galería de la SHCP www.hacienda.gob.mx/museo Biblioteca Miguel Lerdo de Tejada www.hacienda.gob.mx/biblioteca_lerdo Palacio Nacional www.hacienda.gob.mx/palacio_nacional CONTENIDO 4 24 35 36 39 MUSEO DE ARTE OBRAS DE LAS GALERÍA RECINTO DE FONDO HISTÓRICO DE LA SHCP COLECCIONES DE LA SHCP HOMENAJE A DON DE HACIENDA Antiguo Palacio SHCP Guatemala 8, BENITO JUÁREZ ANTONIO del Arzobispado En otros museos Centro Histórico Palacio Nacional, ORTIZ MENA Moneda 4, Segundo Patio Mariano Palacio Nacional Centro Histórico 39 40 42 45 FONDO HISTÓRICO PALACIO BIBLIOTECA CENTRO CULTURAL DE HACIENDA NACIONAL MIGUEL LERDO DE LA SHCP ANTONIO Plaza de la DE TEJADA Av. Hidalgo 81, ORTIZ MENA Constitución s/n República de Centro Histórico Palacio Nacional Centro Histórico El Salvador 49 MUSEO DE arte DE la SHCP • ANTIGUO Palacio DEL arzobispado • Moneda 4 , Centro Histórico NI MUERTO MALO, NI NOVIA FEA PINTURA, DIBUJO, ARTE OBJETO, INSTALACIÓN, FOTOGRAFÍA Y ESCULTURA Público en General SEDE: MUSEO Y GALERÍA DE ARTE DE LA SHCP INAUGURACIÓN: 18 DE OCTUBRE, 19:00 HRS. -

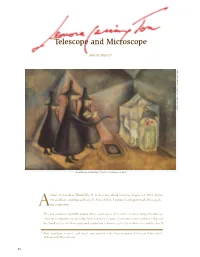

Telescope and Microscope

Telescope and Microscope Alberto Blanco* Private collection. © Estate of Leonora Carrington The Birdmen of Burnley, 45 x 65 cm (oil on canvas). midst the horror of World War II, in the entry dated Tuesday, August 24, 1943, of her extraordinary autobiographical tale, Down Below, Leonora Carrington made this surpris Aing statement: This last sentence, rightfully quoted often, speaks to us of an artist, a human being who did not settle for seeing only part of reality. To the contrary, Leonora Carrington, interested in the Big and the Small —that which in traditional symbolism is known as the Great Mysteries and the Small * Poet, translator, essayist, and visual artist; member of the National Sys tem of Creators of Art (SNCA), [email protected]. 50 Mysteries— never wanted to ignore the great scientific or philosophical themes. Throughout her long, intense life, she was just as interested in astronomy as in astrology, in quantum physics as in the mysteries of the psyche; and at the same time, she never turned her back on what could be considered the minutiae and the details of daily life: her family, her home, her beloved objects, her friends, her pets, her plants. © Estate of Leonora Carrington Private collection. In Leonora Carrington, a profoundly romantic artist —and here, I mean the great English romanticism, that of William Blake, for example— and an eminently practical person co existed without any contradiction. Also found together were a profound sense of humor —also very English, consisting frequently of talking very seriously about the most absurd topics— and the most serious determination to do work that never admitted of the slightest vacillation and suffered no foolishness at all. -

NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012

ISSUE 8 NEWSLETTER Information Exchange in the Caribbean July 2012 MAC AGM 2012 Plans are moving ahead for the 2012 MAC AGM which is to be held in Trinidad, October 21st-24th. For further information please regularly visit the MAC website. Over the last 6 months whilst compiling articles for the newsletter one positive thing that has struck the Secretariat is the increase in the promotion Inside This Issue of information exchange in the Caribbean region. The newsletter has covered a range of conferences occurring this year throughout the Caribbean and 2. Caribbean: Crossroads of several new publications on curatorship in the Caribbean will have been the World Exhibition released by the end of 2012. 3. World Heritage Inscription Ceremony in Barbados Museums and museum staff should make the most of these conferences and 4. Zoology Inspired Art see them not only as a forum to learn about new practices but also as a way 5. 2012 MAC AGM to meet colleagues, not necessarily just in the field of museum work but also 6. New Book Released in many other disciplines. In the present financial situation the world finds ´&XUDWLQJLQWKH&DULEEHDQµ 7. Sint Marteen National itself, it may sound odd to be promoting attendance at conferences and Heritage Foundation buying books but museums must promote continued professional 8. ICOM Advisory Committee development of their staff - if not they will stagnate and the museum will Meeting suffer. 9. Membership Form 10. Association of Caribbean MAC is of course aware that the financial constraints facing many museums at Historians Conference present may limit the physical attendance at conferences. -

![Cecilia De Torres, Ltd. [Mail=Ceciliadetorres.Com@Mail181.Atl21.Rsgsv.Net] En Nombre De Cecilia De Torres, Ltd](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6207/cecilia-de-torres-ltd-mail-ceciliadetorres-com-mail181-atl21-rsgsv-net-en-nombre-de-cecilia-de-torres-ltd-496207.webp)

Cecilia De Torres, Ltd. [[email protected]] En Nombre De Cecilia De Torres, Ltd

De: Cecilia de Torres, Ltd. [[email protected]] en nombre de Cecilia de Torres, Ltd. [[email protected]] Enviado el: jueves, 01 de octubre de 2015 12:49 p.m. Para: Alison Graña Asunto: The South was Their North: Artists of the Torres-García Workshop- Now open through January 2016 Cecilia de Torres, Ltd. invites you to The South was Their North: Artists of the Torres-García Workshop, an exhibition of paintings, sculpture, wood assemblages, furniture and ceramics by Julio Alpuy, Gonzalo Fonseca, José Gurvich, Francisco Matto, Manuel Pailós, Augusto Torres, Horacio Torres and Joaquín Torres-García, on view from September 2015 through January 2016. Related to the upcoming retrospective exhibition, Joaquin Torres-García: The Arcadian Modern at the Museum of Modern Art, Cecilia de Torres, Ltd. presents an aspect of the artist's endeavors that is inextricably associated with his personality and his career: the creation of a school of art that would realize “Constructive Universalism,” his theory of a unified aesthetic based on the visual canon he developed. Torres-García’s ambition was to establish an autonomous artistic tradition based on Constructive Universalism that would eventually expand to all the Americas. This utopian undertaking occupied the last fifteen years of his life as an artist and teacher to new generations, leaving a considerable body of work and an indelible mark on South America’s modern art. The works in this exhibition date from 1936 to the 1980s. Our intent is to present work by this group of exceptional artists that is emblematic of their individuality, works of mature achievement as well as of their constructivist origins.