Accepted Manuscript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’

Aditya Hans Prasad WGSS 07 Professor Douglas Moody April 2018. Of Monsters and Mothers: Representations of Motherhood in ‘Alien’ Released in 1979, director Ridley Scott’s film Alien is renowned as one of the few science fiction films that surpasses most horror films in its power to terrify an audience. The film centers on the crew of the spaceship ‘Nostromo’, and how the introduction of an unknown alien life form wreaks havoc on the ship. The eponymous Alien individually murders each member of the crew, aside from the primary antagonist Ripley, who manages to escape. Interestingly, the film uses subtle representations of motherhood in order to create a truly scary effect. These representations are incredibly interesting to study, as they tie in to various existing archetypes surrounding motherhood and the concept of the ‘monstrous feminine’. In her essay ‘Alien and the Monstrous Feminine’, Barbara Creed discusses the various notions that surround motherhood. First, she writes about the “ancient archaic figure who gives birth to all living things” (Creed 131). Essentially, she discusses the great mother figures of the mythologies of different cultures—Gaia, Nu Kwa, Mother Earth (Creed 131). These characters embody the concept that mothers are nurturing, loving, and caring. Traditionally, stories, films, and other forms of material reiterate and r mothers in this nature. However, there are many notable exceptions to this representation. For example, the primary antagonist in many Brothers Grimm stories are the evil step-mother, a character completely devoid of the maternal warmth and nurturing character of the traditional mother. In Hindu mythology, the goddess Kali is worshipped as the mother of the universe. -

Download Press Release As PDF File

JULIEN’S AUCTIONS - PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: JULIEN’S AUCTIONS ANNOUNCES PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN Emmy, Grammy and Academy Award Winning Hollywood Legend’s Trademark White Suit Costume, Iconic Arrow through the Head Piece, 1976 Gibson Flying V “Toot Uncommons” Electric Guitar, Props and Costumes from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid, Little Shop of Horrors and More to Dazzle the Auction Stage at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills All of Steve Martin’s Proceeds of the Auction to be Donated to BenefitThe Motion Picture Home in Honor of Roddy McDowall SATURDAY, JULY 18, 2020 Los Angeles, California – (June 23rd, 2020) – Julien’s Auctions, the world-record breaking auction house to the stars, has announced PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF STEVE MARTIN, an exclusive auction event celebrating the distinguished career of the legendary American actor, comedian, writer, playwright, producer, musician, and composer, taking place Saturday, July 18th, 2020 at Julien’s Auctions in Beverly Hills and live online at juliensauctions.com. It was also announced today that all of Steve Martin’s proceeds he receives from the auction will be donated by him to benefit The Motion Picture Home in honor of Roddy McDowall, the late legendary stage, film and television actor and philanthropist for the Motion Picture & Television Fund’s Country House and Hospital. MPTF supports working and retired members of the entertainment community with a safety net of health and social -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

Jump Point 06.04 – Scoring

FROM THE COCKPIT IN THIS ISSUE >>> 03 BEHIND THE SCREENS : Composers 19 WORK IN PROGRESS : Origin 100 Series 35 WHITLEY’S GUIDE : 300i 39 WHERE IN THE ‘VERSE? ISSUE: 06 04 40 ONE QUESTION PART 2: What was the first game & system you played? Editor: David Ladyman Roving Correspondent: Ben Lesnick Layout: Michael Alder FROM THE COCKPIT GREETINGS, CITIZENS! As promised last month, we deliver the parts we a couple weeks ago. I am boggled by the number of couldn’t fit in the March issue. We have interviews zeros that entails, and I can do no better than quote with the two primary composers for Squadron 42 Chris in saying, “It’s your belief in the project, from the and SC Persistent Universe music (Geoff Zanelli and earliest backers to those relatively new to the ’verse, Pedro Camacho, respectively) — basically Part 4 of that make it all possible.” our three-part Audio Behind the Screens discussions. The body of previous work for each of these We also hit Alpha 3.1 on schedule, with plenty of composers is stellar, and it appears that they are expanded role-playing features (including a character going above and beyond with CIG’s soundtracks. customizer and service beacons), with a dozen new personal weapons, and with five new flyable (or We also have the second half of the CIG staff responses driveable) craft: the Cyclone, Reclaimer, Terrapin, to our One Question, for your reading pleasure: What Razor and Kue. Your enthusiasm is so important in was the first electronic or computer game you can fueling the drive of everyone at Cloud Imperium remember playing, and on what system? Games to continue creating and innovating in ways that others can only dream of. -

The New Hollywood Films

The New Hollywood Films The following is a chronological list of those films that are generally considered to be "New Hollywood" productions. Shadows (1959) d John Cassavetes First independent American Film. Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966) d. Mike Nichols Bonnie and Clyde (1967) d. Arthur Penn The Graduate (1967) d. Mike Nichols In Cold Blood (1967) d. Richard Brooks The Dirty Dozen (1967) d. Robert Aldrich Dont Look Back (1967) d. D.A. Pennebaker Point Blank (1967) d. John Boorman Coogan's Bluff (1968) – d. Don Siegel Greetings (1968) d. Brian De Palma 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) d. Stanley Kubrick Planet of the Apes (1968) d. Franklin J. Schaffner Petulia (1968) d. Richard Lester Rosemary's Baby (1968) – d. Roman Polanski The Producers (1968) d. Mel Brooks Bullitt (1968) d. Peter Yates Night of the Living Dead (1968) – d. George Romero Head (1968) d. Bob Rafelson Alice's Restaurant (1969) d. Arthur Penn Easy Rider (1969) d. Dennis Hopper Medium Cool (1969) d. Haskell Wexler Midnight Cowboy (1969) d. John Schlesinger The Rain People (1969) – d. Francis Ford Coppola Take the Money and Run (1969) d. Woody Allen The Wild Bunch (1969) d. Sam Peckinpah Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice (1969) d. Paul Mazursky Butch Cassidy & the Sundance Kid (1969) d. George Roy Hill They Shoot Horses, Don't They? (1969) – d. Sydney Pollack Alex in Wonderland (1970) d. Paul Mazursky Catch-22 (1970) d. Mike Nichols MASH (1970) d. Robert Altman Love Story (1970) d. Arthur Hiller Airport (1970) d. George Seaton The Strawberry Statement (1970) d. -

Timeline: Music Evolved the Universe in 500 Songs

Timeline: Music Evolved the universe in 500 songs Year Name Artist Composer Album Genre 13.8 bya The Big Bang The Universe feat. John The Sound of the Big Unclassifiable Gleason Cramer Bang (WMAP) ~40,000 Nyangumarta Singing Male Nyangumarta Songs of Aboriginal World BC Singers Australia and Torres Strait ~40,000 Spontaneous Combustion Mark Atkins Dreamtime - Masters of World BC` the Didgeridoo ~5000 Thunder Drum Improvisation Drums of the World Traditional World Drums: African, World BC Samba, Taiko, Chinese and Middle Eastern Music ~5000 Pearls Dropping Onto The Jade Plate Anna Guo Chinese Traditional World BC Yang-Qin Music ~2800 HAt-a m rw nw tA sxmxt-ib aAt Peter Pringle World BC ~1400 Hurrian Hymn to Nikkal Tim Rayborn Qadim World BC ~128 BC First Delphic Hymn to Apollo Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Epitaph of Seikilos Petros Tabouris The Hellenic Art of Music: World Music of Greek Antiquity ~0 AD Magna Mater Synaulia Music from Ancient Classical Rome - Vol. 1 Wind Instruments ~ 30 AD Chahargan: Daramad-e Avval Arshad Tahmasbi Radif of Mirza Abdollah World ~??? Music for the Buma Dance Baka Pygmies Cameroon: Baka Pygmy World Music 100 The Overseer Solomon Siboni Ballads, Wedding Songs, World and Piyyutim of the Sephardic Jews of Tetuan and Tangier, Morocco Timeline: Music Evolved 2 500 AD Deep Singing Monk With Singing Bowl, Buddhist Monks of Maitri Spiritual Music of Tibet World Cymbals and Ganta Vihar Monastery ~500 AD Marilli (Yeji) Ghanian Traditional Ghana Ancient World Singers -

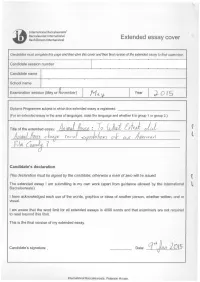

This Cover and Their Final Version Extended

then this cover and their final version extended and whether it is group 1 or Peterson :_:::_.,·. ,_,_::_ ·:. -. \")_>(-_>·...·,: . .>:_'_::°::· ··:_-'./·' . /_:: :·.·· . =)\_./'-.:":_ .... -- __ · ·, . ', . .·· . Stlpervisot1s t~pe>rt ~fld declaration J:h; s3pervi;o(,r;u~f dompietethisreport,. .1ign .the (leclaratton andtfien iiv~.ihe pna:1 ·tersion·...· ofth€7 essay; with this coyerattachedt to the Diploma Programme coordinator. .. .. .. ::,._,<_--\:-.·/·... ":";":":--.-.. ·. ---- .. ,>'. ·.:,:.--: <>=·. ;:_ . .._-,..-_,- -::,· ..:. 0 >>i:mi~ ~;!~;:91'.t~~~1TAt1.tte~) c P1~,§.~p,rmmeht, ;J} a:,ir:lrapriate, on the candidate's perforrnance, .111e. 9q1Jtext ·;n •.w111ctrth~ ..cahdtdatei:m ·.. thft; J'e:~e,~rch.·forf fle ...~X: tendfKI essay, anydifflcu/ties ef1COUntered anq ftCJW thes~\WfJ(fj ()VfJfCOfflf! ·(see .· •tl1i! ext~nciede.ssay guide). The .cpncl(ldipg interview .(vive . vope) ,mt;}y P.fOvidtli .US$ftJf .informf.ltion: pom1r1~nt~ .can .flelp the ex:amr1er award.a ··tevetfot criterion K.th9lisJtcjudgrpentJ. po not. .comment ~pverse personal circumstan9~s that•· m$iiybave . aff.ected the candidate.\lftl'1e cr.rrtotJnt ottime.spiimt qa;ndidate w~s zero, Jt04 must.explain tf1is, fn particular holft!1t was fhf;Jn ppssible .to ;;1.uthentic;at? the essa~ canciidaJe'sown work. You rnay a-ttachan .aclditfonal sherJtJf th.ere isinspfffpi*?nt f pr1ce here,·.···· · Overall, I think this paper is overambitious in its scope for the page length / allowed. I ~elieve it requires furt_her_ editing, as the "making of" portion takes up too ~ large a portion of the essay leaving inadequate page space for reflections on theory and social relevance. The section on the male gaze or the section on race relations in comedy could have served as complete paper topics on their own (although I do appreciate that they are there). -

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in the Guardian, June 2007

1,000 Films to See Before You Die Published in The Guardian, June 2007 http://film.guardian.co.uk/1000films/0,,2108487,00.html Ace in the Hole (Billy Wilder, 1951) Prescient satire on news manipulation, with Kirk Douglas as a washed-up hack making the most of a story that falls into his lap. One of Wilder's nastiest, most cynical efforts, who can say he wasn't actually soft-pedalling? He certainly thought it was the best film he'd ever made. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (Tom Shadyac, 1994) A goofy detective turns town upside-down in search of a missing dolphin - any old plot would have done for oven-ready megastar Jim Carrey. A ski-jump hairdo, a zillion impersonations, making his bum "talk" - Ace Ventura showcases Jim Carrey's near-rapturous gifts for physical comedy long before he became encumbered by notions of serious acting. An Actor's Revenge (Kon Ichikawa, 1963) Prolific Japanese director Ichikawa scored a bulls-eye with this beautifully stylized potboiler that took its cues from traditional Kabuki theatre. It's all ballasted by a terrific double performance from Kazuo Hasegawa both as the female-impersonator who has sworn vengeance for the death of his parents, and the raucous thief who helps him. The Addiction (Abel Ferrara, 1995) Ferrara's comic-horror vision of modern urban vampires is an underrated masterpiece, full- throatedly bizarre and offensive. The vampire takes blood from the innocent mortal and creates another vampire, condemned to an eternity of addiction and despair. Ferrara's mob movie The Funeral, released at the same time, had a similar vision of violence and humiliation. -

1 Filmová Hudba 1. 1 Definice Filmové Hudby

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Pedagogická fakulta Katedra hudební výchovy Bakalá řská práce Veronika Lyková Obor: Spole čenské v ědy se zam ěř ením na vzd ělávání a hudební kultura se zam ěř ením na vzd ělávání Hudba ve fantasy filmech Vedoucí práce: MgA. Petr Martínek Olomouc 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem svou bakalá řskou práci zpracovala samostatn ě a že jsem uvedla veškerou literaturu a zdroje, které jsem k práci využila. V Olomouci dne 17. 6. 2017 …..…..…..…………………. Podpis Děkuji vedoucímu své bakalá řské práce, panu MgA. Petru Martínkovi, za trp ělivost a ochotu. Dále bych ráda pod ěkovala paní Mgr. Gabriele Všeti čkové, Ph.D., za poskytnuté rady, a panu Mgr. Filipu T. Krej čímu, Ph.D., za doporu čenou literaturu. Obsah Úvod .................................................................................................................................. 7 1 Historie filmové hudby .................................................................................................. 9 1. 1 Definice filmové hudby......................................................................................... 9 1. 2 Historie filmové hudby ......................................................................................... 9 1. 3 Tvorba filmové hudby ......................................................................................... 10 2 Howard Shore .............................................................................................................. 12 2. 1 Pán prsten ů ......................................................................................................... -

We Have Liftoff! the Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 P.M

POPS FOUR We Have Liftoff! The Rocket City in Space SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 29, 2020 • 7:30 p.m. • MARK C. SMITH CONCERT HALL, VON BRAUN CENTER Huntsville Symphony Orchestra • C. DAVID RAGSDALE, Guest Conductor • GREGORY VAJDA, Music Director One of the nation’s major aerospace hubs, Huntsville—the “Rocket City”—has been heavily invested in the industry since Operation Paperclip brought more than 1,600 German scientists to the United States between 1945 and 1959. The Army Ballistic Missile Agency arrived at Redstone Arsenal in 1956, and Eisenhower opened NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in 1960 with Dr. Wernher von Braun as Director. The Redstone and Saturn rockets, the “Moon Buggy” (Lunar Roving Vehicle), Skylab, the Space Shuttle Program, and the Hubble Space Telescope are just a few of the many projects led or assisted by Huntsville. Tonight’s concert celebrates our community’s vital contributions to rocketry and space exploration, at the most opportune of celestial conjunctions: July 2019 marked the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon-landing mission, and 2020 brings the 50th anniversary of the U.S. Space and Rocket Center, America’s leading aerospace museum and Alabama’s largest tourist attraction. S3, Inc. Pops Series Concert Sponsors: HOMECHOICE WINDOWS AND DOORS REGIONS BANK Guest Conductor Sponsor: LORETTA SPENCER 56 • HSO SEASON 65 • SPRING musical selections from 2001: A Space Odyssey Richard Strauss Fanfare from Thus Spake Zarathustra, op. 30 Johann Strauss, Jr. On the Beautiful Blue Danube, op. 314 Gustav Holst from The Planets, op. 32 Mars, the Bringer of War Venus, the Bringer of Peace Mercury, the Winged Messenger Jupiter, the Bringer of Jollity INTERMISSION Mason Bates Mothership (2010, commissioned by the YouTube Symphony) John Williams Excerpts from Close Encounters of the Third Kind Alexander Courage Star Trek Through the Years Dennis McCarthy Jay Chattaway Jerry Goldsmith arr. -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made.