Contemporary Film Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature of Elliot Goldenthal's Music

The Nature of Elliot Goldenthal’s Music & A Focus on Alien 3 (& other scores) There is “something different” about Elliot Goldenthal’s music. There is also considerable brain and brawn in Elliot Goldenthal’s film music. His style is difficult to label because his approach is so eclectic depending on the project. Sometimes I feel he is fundamentally an independent art-house composer (perhaps Frida, say, and The Good Thief) although he can demonstrate thrilling orchestral power in scores such as Sphere and the Batman movies that I personally quite enjoyed. Overall he shows a Late Modernist temperament, musically an American Bohemian, but nevertheless grounded somewhat in the mainstream traditions (certainly at least traditional notation). His polystylism (eclectism) is a postmodern characteristic. An excellent example of polystylism is his score for Titus (and Good Thief to a lesser extent, and even an example or two in Alien 3) with the diverse or even odd juxtaposition of genres (symphonic-classical, rock, etc.) that represents in one score the type of projects he collectively undertook over the last fifteen years or so. There is not one clear-cut musical voice, in other words, but a mixture or fusion of different styles. It is, in part, his method of organization. Loosely speaking, his music is avant-garde but certainly not radically so--as in the case of John Cage with his aleatoric (random) music and quite non-traditional notation (although Goldenthal’s music can at select times be aleatoric in effect when he utilizes electronic music, quarter-toning, and other devices). He is experimental and freewheeling but certainly this tendency is not overblown and expanded into the infinite! He definitely takes advantage of what technology has to offer (MIDI applications, timbre sampling, synthesizer usage, etc.) but does not discard what traditions are useful for him to express his vision of musical art. -

Dive 010 - Sea Docs

Dive 010 - Sea Docs Our last collection of Sea Genre films focusing on the watery realms of The Soundtrack Zone may be classified as films in the Sea Documentary genre or, for short, Sea Docs. Two early examples of scores for a Sea Doc film were those composed by Paul J. Smith for two Walt Disney’s True-Life Adventures films: Beaver Valley (1950) and Prowlers of the Everglades (1953). A Disneyland LP (WDL-4011 – released in 1975) included the following tracks from those two films: Beaver Valley (7:15) - Beaver Valley Theme - Baby Ducks - Beaver Romance - Salmon Run – Otters Prowlers of the Everglades (4:09) - Alligators - Swamp Deluge - Otters And Gators LP In 1956, Walt Disney’s Disneyland WDL-4006 LP presented Paul J. Smith’s score for another True-Life Adventure film, Secrets of Life. One of the album’s suites, “Under The Sea And Along The Shore,” includes several underwater-related tracks: Decorator Crab, Jellyfish, Angler Fish, and Fiddler Crabs (04:21) LP Three years later, in 1959, Walt Disney released a short film titled Mysteries of the Deep (23:55). Three of these films – Beaver Valley, Prowlers of the Everglades, and Mysteries of the Deep are available on DVD (see DVD 1 photo below). Secrets of Life is included on DVD 2 (see photo below). DVD 1 DVD 2 Unfortunately none of the scores for these Walt Disney underwater-related films have been commercially issued on CD. Fortunately, the scores of many subsequent Sea Docs films have been released over the years on LP and/or CD. -

BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM at CANNES British Entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’Ve Got to Talk About Kevin Dir

London May 10 2011: For immediate release BFI CELEBRATES BRITISH FILM AT CANNES British entry for Cannes 2011 Official Competition We’ve Got to Talk About Kevin dir. Lynne Ramsay UK Film Centre supports delegates with packed events programme 320 British films for sale in the market A Clockwork Orange in Cannes Classics The UK film industry comes to Cannes celebrating the selection of Lynne Ramsay’s We Need to Talk About Kevin for the official competition line-up at this year’s festival, Duane Hopkins’s short film, Cigarette at Night, in the Directors’ Fortnight and the restoration of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, restored by Warner Bros; in Cannes Classics. Lynne Ramsay’s We Need To Talk About Kevin starring Tilda Swinton was co-funded by the UK Film Council, whose film funding activities have now transferred to the BFI. Duane Hopkins is a director who was supported by the UK Film Council with his short Love Me and Leave Me Alone and his first feature Better Things. Actor Malcolm McDowell will be present for the screening of A Clockwork Orange. ITV Studios’ restoration of A Night to Remember will be screened in the Cinema on the Beach, complete with deckchairs. British acting talent will be seen in many films across the festival including Carey Mulligan in competition film Drive, and Tom Hiddleston & Michael Sheen in Woody Allen's opening night Midnight in Paris The UK Film Centre offers a unique range of opportunities for film professionals, with events that include Tilda Swinton, Lynne Ramsay and Luc Roeg discussing We Need to Talk About Kevin, The King’s Speech producers Iain Canning and Gareth Unwin discussing the secrets of the film’s success, BBC Film’s Christine Langan In the Spotlight and directors Nicolas Winding Refn and Shekhar Kapur in conversation. -

Knowledge Organiser

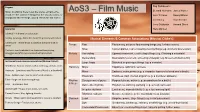

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

Cas Awards April 17, 2021

PRESENTS THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS APRIL 17, 2021 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS PRE-SHOW MESSAGES PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Non-Theatrical Motion Pictures or Limited Series PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Documentary PRESIDENT’S REMARKS Karol Urban CAS MPSE Year in Review, In Memoriam INSTALLATION OF NEW BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Series – Half-Hour PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY Student Recognition Award PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Product for Production PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Product for Post-Production CAS RED CARPET PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Non-Fiction, Variety, Music, Series or Specials PRESENTATION OF CAS FILMMAKER AWARD TO GEORGE CLOONEY PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Animated CAS RED CARPET PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Television Series – One Hour PRESENTATION OF CAS CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD TO WILLIAM B. KAPLAN CAS PRESENTATION OF THE CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARD FOR Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures – Live Action AFTER-AWARDS VIRTUAL NETWORKING RECEPTION THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY 1 THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS DIAMOND SPONSORS PLATINUM SPONSORS STUDENT RECOGNITION AWARD SPONSORS GOLD SPONSORS GROUP SILVER SPONSORS THE 57TH ANNUAL CAS AWARDS CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY 3 PRESIDENT’S LETTER Welcome to the 57th CAS Awards! It has been over a year since last we came together to celebrate our sound mixing community and we are so very happy to see you all. -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S. -

William B. Kaplan CAS

Career Achievement Award Recipient William B. Kaplan CAS CAS Filmmaker Award Recipient George SPRING Clooney 2021 Overcoming Atmos Anxiety • Playing Well with Other Departments • RF in the 21st Century Remote Mixing in the Time of COVID • Return to the Golden Age of Booming Sound Ergonomics for a Long Career • The Evolution of Noise Reduction FOR YOUR CONSIDERATION CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS NOMINEE MOTION PICTURE LIVE ACTION PRODUCTION MIXER DREW KUNIN RERECORDING MIXERS REN KLYCE, DAVID PARKER, NATHAN NANCE SCORING MIXER ALAN MEYERSON, CAS ADR MIXER CHARLEEN RICHARDSSTEEVES FOLEY MIXER SCOTT CURTIS “★★★★★. THE FILM LOOKS AND SOUNDS GORGEOUS.” THE GUARDIAN “A WORK OF DAZZLING CRAFTSMANSHIP.” THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER “A stunning and technically marvelous portrait of Golden Era Hollywood that boasts MASTERFUL SOUND DESIGN.” MIRROR CAS QUARTERLY, COVER 2 REVISION 1 NETFLIX: MANK PUB DATE: 03/15/21 BLEED: 8.625” X 11.125” TRIM: 8.375” X 10.875” INSIDE THIS ISSUE SPRING 2021 CAREER ACHIEVEMENT AWARD RECIPIENT WILLIAM B. KAPLAN CAS | 20 DEPARTMENTS The President’s Letter | 4 From the Editor | 6 Collaborators | 8 Learn about the authors of your stories 26 34 Announcements | 10 In Remembrance | 58 Been There Done That |59 CAS members check in The Lighter Side | 61 See what your colleagues are up to 38 52 FEATURES A Brief History of Noise Reduction | 15 Remote Mixing in the Time of COVID: User Experiences | 38 RF in the Twenty-First Century |18 When mix teams and clients are apart Filmmaker Award: George Clooney | 26 Overcoming Atmos Anxiety | 42 Insight to get you on your way The 57th Annual CAS Awards Nominees for Outstanding Achievement Playing Well with Other Production in Sound Mixing for 2020 | 28 Departments | 48 The collaborative art of entertainment Outstanding Product Award Nominees| 32 Sound Ergonomics for a Long Career| 52 Return to the Golden Age Staying physically sound on the job Cover: Career Achievement Award of Booming | 34 recipient William B. -

To Rock Or Not Torock?

v7n3cov 4/21/02 10:12 AM Page c1 ORIGINAL MUSIC SOUNDTRACKS FOR MOTION PICTURES AND TV V OLUME 7, NUMBER 3 Exclusive interview with Tom Conti! TOTO ROCK ROCK OROR NOTNOT TOROCK?TOROCK? CanCan youyou smellsmell whatwhat JohnJohn DebneyDebney isis cooking?cooking? JOHNWILLIAMSJOHNWILLIAMS’’ HOOKHOOK ReturnReturn toto NeverlandNeverland DIALECTDIALECT OFOF DESIREDESIRE TheThe eroticerotic voicevoice ofof ItalianItalian cinemacinema THETHE MANWHO CAN-CAN-CANCAN-CAN-CAN MeetMeet thethe maestromaestro ofof MoulinMoulin Rouge!Rouge! PLUSPLUS HowardHoward ShoreShore && RandyRandy NewmanNewman getget theirs!theirs! 03> 7225274 93704 $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada v7n3cov 4 /19/02 4 :29 PM P age c2 composers musicians record labels music publishers equipment manufacturers software manufacturers music editors music supervisors music clear- Score with ance arrangers soundtrack our readers. labels contractors scoring stages orchestrators copyists recording studios dubbing prep dubbing rescoring music prep scoring mixers Film & TV Music Series 2002 If you contribute in any way to the film music process, our four Film & TV Music Special Issues provide a unique marketing opportunity for your talent, product or service throughout the year. Film & TV Music Summer Edition: August 20, 2002 Space Deadline: August 1 | Materials Deadline: August 7 Film & TV Music Fall Edition: November 5, 2002 Space Deadline: October 18 | Materials Deadline: October 24 LA Judi Pulver (323) 525-2026, NY John Troyan (646) 654-5624, UK John Kania +(44-208) 694-0104 www.hollywoodreporter.com v7n03 issue 4/19/02 3:09 PM Page 1 CONTENTS MARCH/APRIL 2002 cover story departments 14 To Rock or Not to Rock? 2 Editorial Like it or hate it (okay, hate it), the rock score is Happy 70th, Maestro! here to stay. -

Stephanie's Harp Repertoire List

Stephanie’s Harp Repertoire List Classical Adagio – Arcangelo Corelli Air from Water Music – George Frideric Handel Andaluza – Enrique Granados Aria – Johann Kuhnau Aria – Leonardo Vinci Arioso – Johan Sebastian Bach Au Bord Du Ruisseau – Henriette Renié Ave Maria – Franz SchuBert Barcarolle – Jacques OffenBach Bridal Chorus – Richard Wagner Bourée from Cello Suite No. 3 in C – Johann Sebastian Bach Cannon in D – Johann PachelBel Caro Mio Ben – Giuseppe Giordano Clair De Lune – Claude Debussy En Bateau – Claude Debussy Finlandia – Jan Sibelius Für Elise – Ludwig van Beethoven Gavotte – Christoph W. von Gluck Girl with the Flaxen Hair (La fille aux cheveux de lin) – Claude Debussy Jesu Joy Of Man’s Desiring – Johann Sebastian Bach Largo – George Frideric Handel Larghetto –George Frideric Handel Londonderry Air/O Danny Boy – Irish Air Love’s Greeting (Salut D’Amour) – Edward Elgar Meditation from Thais – Jules Massenet Moderato Cantabile – Frederic Chopin Moonlight Sonata – Ludwig van Beethoven Musetta’s Waltz – Giacomo Puccini Nocturne Op. 9 No. 2 – Frederic Chopin Ode to Joy – Ludwig van Beethoven O Mio Babbino Caro – Giacomo Puccini On Wings of Song – Felix Mendelssohn Passacaille – George Frideric Handel Pastorale – Arcangelo Corelli Pavane – GaBriel Fauré Prelude in C – Johann Sebastian Bach Prelude Op. 28, No. 7 – Frederic Chopin Reverie – Claude Debussy Romanza – Anonymous Sheep May Safely Graze – Johann Sebastian Bach Serenade – Franz SchuBert Simple Gifts – Joseph Brackett/Shaker Song Spring – Antonio Vivaldi The Beautiful Blue