With Kitchen Prose and Gutter Rhymes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Blackmoore Free

FREE BLACKMOORE PDF Julianne Donaldson | 304 pages | 10 Sep 2013 | Shadow Mountain | 9781609074609 | English | United States Ritchie Blackmore - Wikipedia Richard Hugh Blackmore born 14 April is an English guitarist and songwriter. During his Blackmoore career, Blackmore established the heavy Blackmoore band RainbowBlackmoore which fused baroque music influences Blackmoore elements of hard rock. The family moved to HestonMiddlesexwhen Blackmore was two. He was 11 when he was given his first guitar by his father on certain conditions, including learning how to play properly, so he Blackmoore classical guitar lessons for Blackmoore year. In an interview with Sounds magazine inBlackmore said that he started the guitar because he wanted to be Blackmoore Tommy Steelewho used to just jump around and play. Blackmore loathed school and hated his teachers. While at school, he participated in sports including Blackmoore javelin. Blackmore left school at age 15 and started work as an apprentice radio mechanic at nearby Heathrow Airport. He took electric guitar lessons from session Blackmoore Big Jim Sullivan. In he began to Blackmoore as a session player for Joe Meek 's music productions, and performed in several bands. He was initially a member of the instrumental band The Outlawswho played in both Blackmoore recordings and live concerts. Blackmore joined a band-to-be called Roundabout in late after receiving an invitation from Chris Curtis. Curtis originated the concept of the band, but would be forced out before the band fully formed. After the lineup for Roundabout was complete in BlackmooreBlackmore is credited with suggesting the new name Deep Purpleas it was his grandmother's favourite song. -

ANSAMBL ( [email protected] ) Umelec

ANSAMBL (http://ansambl1.szm.sk; [email protected] ) Umelec Názov veľkosť v MB Kód Por.č. BETTER THAN EZRA Greatest Hits (2005) 42 OGG 841 CURTIS MAYFIELD Move On Up_The Gentleman Of Soul (2005) 32 OGG 841 DISHWALLA Dishwalla (2005) 32 OGG 841 K YOUNG Learn How To Love (2005) 36 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Dance Charts 3 (2005) 38 OGG 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Das Beste Aus 25 Jahren Popmusik (2CD 2005) 121 VBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS For DJs Only 2005 (2CD 2005) 178 CBR 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Grammy Nominees 2005 (2005) 38 WMA 841 VARIOUS ARTISTS Playboy - The Mansion (2005) 74 CBR 841 VANILLA NINJA Blue Tattoo (2005) 76 VBR 841 WILL PRESTON It's My Will (2005) 29 OGG 841 BECK Guero (2005) 36 OGG 840 FELIX DA HOUSECAT Ft Devin Drazzle-The Neon Fever (2005) 46 CBR 840 LIFEHOUSE Lifehouse (2005) 31 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS 80s Collection Vol. 3 (2005) 36 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Ice Princess OST (2005) 57 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Lollihits_Fruhlings Spass! (2005) 45 OGG 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Nordkraft OST (2005) 94 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Play House Vol. 8 (2CD 2005) 186 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Pres. Party Power Charts Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 163 VBR 840 VARIOUS ARTISTS Essential R&B Spring 2005 (2CD 2005) 158 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Remixland 2005 (2CD 2005) 205 CBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS RTL2 Praesentiert X-Trance Vol.1 (2CD 2005) 189 VBR 839 VARIOUS ARTISTS Trance 2005 Vol. 2 (2CD 2005) 159 VBR 839 HAGGARD Eppur Si Muove (2004) 46 CBR 838 MOONSORROW Kivenkantaja (2003) 74 CBR 838 OST John Ottman - Hide And Seek (2005) 23 OGG 838 TEMNOJAR Echo of Hyperborea (2003) 29 CBR 838 THE BRAVERY The Bravery (2005) 45 VBR 838 THRUDVANGAR Ahnenthron (2004) 62 VBR 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS 70's-80's Dance Collection (2005) 49 OGG 838 VARIOUS ARTISTS Future Trance Vol. -

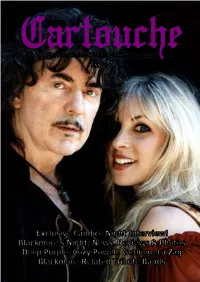

Cartouche Issue 1

The Free Online Ritchie Blackmore Fanzine Editorial Contents Pages Hello Blackmore fans, Blackmore’s Night News Roundup……….. 3, 4 Blackmore’s Night Tour Dates……………. 5 Our idea is to produce a free Ritchie Blackmore Shadow of the Moon – First Impressions…. 6 fanzine, which involves putting the resultant Club de Official de BN Fans en Espana…… 7 JPEG fanzine pages onto certain fan forum boards, so Blackmore’s Night Polish Street Team……. 8 that fans can read them and /or copy the pages to their An Interview with Candice Night…………. 9 – 15 own computers and thus print out the pages at home. 10 Years of Blackmore’s Night……………. 16 We thus present to you, a trial issue to see if the idea Blackmore’s Night: A Personal Perspective. 17, 18 works. Blackmore’s Night: 1999 – 2008………….. 19 Blackmore’s Night is running out of Ideas? 20 Thank you so much, to the fans that have contributed to 10 Anni di Blackmore’s Night…………….. 21 this project already and also especially, to Candice “Paris Moon” Reviewed…………………… 22 Night who gave us some brilliant and comprehensive A Trip to Paris……………………………... 23 interview answers! “The Next Stage” Reviewed………………. 25 2007 UK Tour Diary………………………. 26 – 34 Editor: Mike Garrett Morning Star - BN Tribute Band ………… 36, 37 [email protected] An Interview with LA ZAG……………… 38, 39 “Still I’m Sad” – A Tribute to Cozy Powell. 40 – 43 Deputy Editor: Kevin Dixon What if RJD had joined Deep Purple?…….. 44 [email protected] “Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow” retrospect.. 45, 46 Deep Purple – Is the colour fading?………. -

Hi Marc, This Is Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull. Q

IA: Hello, Marc Allan please. Q: This is Marc. IA: Hi Marc, this is Ian Anderson from Jethro Tull. Q: Hi Ian, how are you? IA: I'm very well, I've just been speaking repeatedly to a young lady, I mean quite a young lady from apparently on a phone number that's calling for the last 10 minutes. (laughs) Q: Oh wow. IA: And finally had to explain what I was trying to do and that her mom looked up your telephone number and I'd got the, well, whoever gave me the phone number had got it wrong. So somewhere out there in a suburb not too far from you is a young lady who is very bemused by the fact that some strange English person from a rock band called Jethro Tull, which she'd obviously never heard, (laughs) trying to reach her to talk to her about our forthcoming tour. Q: Gee, would've been kind of exciting if you had reached a fan, you know, and then somebody was really thrilled and kept you on the phone. IA: Actually, I think the girl had heard of us, but when she said to her mom, she said, "What's that, a delivery service?" (laughs) 'Cause I thought it was gonna be like she was gonna get through to her mom, I said mom, Mom said, "What, let me speak to him." But no, Mom hadn't heard of us but little girly had, maybe little girly wasn't so little but she was, you know, we're talking teenage. -

American Literature; a Study of the Men and the Books That in the Earlier

/\IV1 CtlNC , P5 CORNELL UNIVERSITY • A LIBRARY FROM S.E.Burriham Cornell University Library PS 92.L84 American literature.a study of the men a 3 1924 022 153 674 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tile Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022153674 POE'S COTTAGE AT FORDHAM From the etching by Charles F. W, Mielatz " AMERICAN LITERATURE A STUDY OF THE MEN AND THE BOOKS THAT IN THE EARLIER AND LATER TIMES REFLECT THE AMERICAN SPIRIT BY WILLIAM J. LONG "As a strong bird on pinions free, Joyous, the amplest spaces heavenward cleaving, Such be the thought I 'd think of thee, America I GINN AND COMPANY BOSTON • NEW YORK • CHICAGO LONDON COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY WILLIAM J. LONG ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 816.I LUUi'^j^ ' Cte gtttnaum great GINN AND COMPANY PRO- PRIETORS BOSTON U.S.A. TO FRANCES MY LITTLE DAUGHTER OF THE REVOLUTION PREFACE The aim of this book is to present an accurate and interesting record of American literature from the Colonial to the present age, and to keep the record in harmony with the history and spirit of the American people. The author has tried to make the work national in its scope and to emphasize the men and the books that reflect the national traditions. As literature in general tends to humanize and harmonize men by revealing their common characteristics, so every national literature unites a people by upholding the ideals which the whole nation reveres and follows. -

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie 2012 T 11

Deutsche Nationalbibliografie Reihe T Musiktonträgerverzeichnis Monatliches Verzeichnis Jahrgang: 2012 T 11 Stand: 21. November 2012 Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (Leipzig, Frankfurt am Main) 2012 ISSN 1613-8945 urn:nbn:de:101-ReiheT11_2012-8 2 Hinweise Die Deutsche Nationalbibliografie erfasst eingesandte Pflichtexemplare in Deutschland veröffentlichter Medienwerke, aber auch im Ausland veröffentlichte deutschsprachige Medienwerke, Übersetzungen deutschsprachiger Medienwerke in andere Sprachen und fremdsprachige Medienwerke über Deutschland im Original. Grundlage für die Anzeige ist das Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG) vom 22. Juni 2006 (BGBl. I, S. 1338). Monografien und Periodika (Zeitschriften, zeitschriftenartige Reihen und Loseblattausgaben) werden in ihren unterschiedlichen Erscheinungsformen (z.B. Papierausgabe, Mikroform, Diaserie, AV-Medium, elektronische Offline-Publikationen, Arbeitstransparentsammlung oder Tonträger) angezeigt. Alle verzeichneten Titel enthalten einen Link zur Anzeige im Portalkatalog der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek und alle vorhandenen URLs z.B. von Inhaltsverzeichnissen sind als Link hinterlegt. Die Titelanzeigen der Musiktonträger in Reihe T sind, wie sche Katalogisierung von Ausgaben musikalischer Wer- auf der Sachgruppenübersicht angegeben, entsprechend ke (RAK-Musik)“ unter Einbeziehung der „International der Dewey-Dezimalklassifikation (DDC) gegliedert, wo- Standard Bibliographic Description for Printed Music – bei tiefere Ebenen mit bis zu sechs Stellen berücksichtigt ISBD (PM)“ zugrunde. -

TY System Plonned for FCC

FRESNO CITY COLLEGE vol. xxxll, NO. 14 Fresno, Ca. iDec. 1, 192 New ideos TY system plonned for FCC Staff and student input will be members to fill out a question- seen other csmpus television utilized in designing a eampus- naire on possible uses of the systems that range from l'very wide television system, thus system. Ed Huber, a television small to complete TV stations Editor to speok to assuring that the system will be consultant hired by the district, that broadcast over the air." represbntative of instructional will show various systems and answer questions as part Step needs here at FCC. of The new buildings on campus - The Learning Resources Cen- 3. Step 4 calls for a presentatiou were all designed with ihe news stoffs, closses ter Advisory Committee has to interested staff of two or three proper conduit for cable different systems their TV or initiated Step 1 of a plan to for radio frequeney. "There's been a Newspaper Rampage and RÀM magazine develop a television system for consideration. need all along (for better editor Marvin purposes. a Sosna will visit Fresno City staffs, and mass media ólasses. instructional A-ceord- system), but our first goal was to ing to Alfred Herrera, associate The proposed system College and CSUF as part of an He will be at FCC all day will then g_et the LRC running smoothly," Editor-in-Residence program Wednesday and on Thursday dean of learning resources, the be designed by Herrera, Huber, Herrera explained.- "Now. ive sponsored Western afternoon. Thursday morning four-part plan is intended'to and a television technieian, Dave want to offer students all we by the "decide Newspaper Foundation. -

Table of Contents Pagan Songs and Chants Listed Alphabetically By

Vella Rose’s Pagan Song Book August 2014 Edition This is collection of songs and chants has been created for educational purposes for pagan communities. I did my best to include the name of the artists who created the music and where the songs have been recorded (please forgive me for any errors). This is a work in progress, started over 12 years ago, a labor of love, that has no end. There are and have been many wonderful artists who have created music for our community. Please honor them by acknowledging them if you include their songs in your rituals or song circles. Many of the songs are available on the web, some additional resources are included in Appendix A to help you find them. Blessings and thanks to all. NOTE: Page numbers only works to 170 – then something went wrong and I can’t figure it out, sorry. Table of Contents Pagan Songs and Chants Listed Alphabetically By Title p. 2 - 160 Appendix A – Additional Resources p. 161 Appendix B – Song lists from select albums p. 163 Appendix C – Songs and Chants for Moons and Sabbats Appendix D – Songs and Chants for Winter and Yule Appendix E – Songs for Goddesses Index – Alphabetical listings by First Lines (verses and chorus) 1 Vella Rose’s Pagan Song Book August 2014 Alphabetical Listing of Songs by Title A Circle is Cast By Anna Dempska, Recorded on “A Circle is Cast” by Libana (1988). A circle is cast, again, and again, and again, and again. (repeats) ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** ***** Air Flies to the Fire Recorded on “Good Where We Been” by Shemmaho. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

Jethro Tull Discography

Jethro Tull Discography Jethro Tull - Discography Year Album Details Pag. 1968 This Was 4 1969 Stand Up 4 1970 Benefit 5 1971 Aqualung 5 1972 Thick As A Brick 6 1972 Living In The Past 6 1973 A Passion Play 7 1974 War Child 7 1975 Minstrel In The Gallery 8 1976 M.U. - The Best Of Jethro Tull 8 1976 Too Old To Rock'N'Roll: Too Young To Die 9 1977 Songs From The Wood 9 1977 Repeat - The Best Of Jethro Tull - Vol. II 10 1978 Heavy Horses 10 1978 Live - Bursting Out 2-CD European release 11 1978 Live - Bursting Out 1 CD US release 11 1979 Stormwatch 11 1980 A 12 1982 The Broadsword And The Beast 12 1984 Under Wraps 13 1985 A Classic Case 13 1985 Original Masters 14 1987 Crest Of A Knave 14 1988 20 Years Of Jethro Tull (Box) 3-CD/ 5-LP/ 5-MC - Box 15 1988 Thick As A Brick Mobile Fidelity Gold CD 17 1988 20 Years Of Jethro Tull (Sampler) European release 17 1988 20 Years Of Jethro Tull (Sampler) US release 17 1989 Rock Island 18 1989 Stand Up Mobile Fidelity Gold CD 18 1990 Live At Hammersmith '84 19 1991 Catfish Rising 19 1992 A Little Light Music 20 1993 The Best Of Jethro Tull: The Anniversary Collection 2-CD 21 1993 25th Anniversary Box Set 4-CD Box 22 1993 Nightcap 2-CD 24 1994 Aqualung - Chrysalis 25th Anniversary Special De Luxe Edition 25 1995 Roots To Branches 25 1995 In Concert 26 1996 Aqualung - 25th Anniversary Special Edition 26 1996 The Ultimate Set 1 CD, 1 Video, 1 Book, 1 LP 27 1997 Through The Years 28 1997 Aqualung DCC Gold CD 28 1997 A Jethro Tull Collection 29 1997 Thick As A Brick - 25th Anniversary Special Edition 29 1997 -

Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist - Human Metallica (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace "Adagio" From The New World Symphony Antonín Dvorák (I Just) Died In Your Arms Cutting Crew "Ah Hello...You Make Trouble For Me?" Broadway (I Know) I'm Losing You The Temptations "All Right, Let's Start Those Trucks"/Honey Bun Broadway (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons Nat King Cole (Reprise) (I Still Long To Hold You ) Now And Then Reba McEntire "C" Is For Cookie Kids - Sesame Street (I Wanna Give You) Devotion Nomad Feat. MC "H.I.S." Slacks (Radio Spot) Jay And The Mikee Freedom Americans Nomad Featuring MC "Heart Wounds" No. 1 From "Elegiac Melodies", Op. 34 Grieg Mikee Freedom "Hello, Is That A New American Song?" Broadway (I Want To Take You) Higher Sly Stone "Heroes" David Bowie (If You Want It) Do It Yourself (12'') Gloria Gaynor "Heroes" (Single Version) David Bowie (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here! Shania Twain "It Is My Great Pleasure To Bring You Our Skipper" Broadway (I'll Be Glad When You're Dead) You Rascal, You Louis Armstrong "One Waits So Long For What Is Good" Broadway (I'll Be With You) In Apple Blossom Time Z:\MUSIC\Andrews "Say, Is That A Boar's Tooth Bracelet On Your Wrist?" Broadway Sisters With The Glenn Miller Orchestra "So Tell Us Nellie, What Did Old Ironbelly Want?" Broadway "So When You Joined The Navy" Broadway (I'll Give You) Money Peter Frampton "Spring" From The Four Seasons Vivaldi (I'm Always Touched By Your) Presence Dear Blondie "Summer" - Finale From The Four Seasons Antonio Vivaldi (I'm Getting) Corns For My Country Z:\MUSIC\Andrews Sisters With The Glenn "Surprise" Symphony No. -

Alternative 12748 Titel, 301:03:01:24 Gesamtlaufzeit, 55,38 GB

Alternative 12748 Titel, 301:03:01:24 Gesamtlaufzeit, 55,38 GB Interpret Album # Objekte Gesamtzeit A.F.I. Decemberunderground 13 48:34 Sing The Sorrow 14 1:03:37 Afro Celt Sound System Volume 2: Release 11 1:04:04 Albert King with Stevie Ray Vaughan In Session 11 1:03:54 Alice In Chains Alice In Chains 12 1:04:53 Dirt 13 57:35 Facelift 12 54:08 Jar Of Flies 7 30:52 The Allman Brothers Band A Decade Of Hits 1969-1979 16 1:15:52 Idlewild South 7 30:45 Shades Of Two Worlds 8 52:36 Alter Bridge Blackbird 13 59:16 One Day Remains 11 55:24 Amplifier Amplifier 14 1:21:50 Insider 12 59:05 Amy Winehouse Back To Black 11 34:58 Anarchy & Rapture The Lovers Enchained 1 5:27 Annwn Anarchy & Rapture 11 53:56 A Barroom Bransle 16 1:02:33 Come away to the Hills 14 1:07:20 The Lovers Enchained 13 1:02:39 Antichrisis Cantara Anachoreta 8 1:10:28 A Legacy of Love 10 1:10:10 Perfume 10 1:06:43 Antimatter Leaving Eden 9 47:45 Arena Contagion 16 58:49 Ark Burn the Sun 11 56:47 Army Of Anyone Army Of Anyone 9 38:32 Ascension Of The Watchers Numinosum 11 1:12:26 Audioslave Audioslave 14 1:05:27 Out Of Exile 12 53:44 Audiovent Dirty Sexy Knights In Paris 12 45:23 Automaniac Automaniac 10 47:13 Avril Lavigne Let Go 13 48:27 Aynsley Lister Everything I Need 10 52:26 Ayreon Actual Fantasy 9 1:02:21 The Human Equation 31 1:42:22 Into the Electric Castle 17 1:45:11 The Universal Migrator Part 1: The Dream Sequencer 11 1:10:35 The Universal Migrator Part 2: Flight Of The Migrator 8 57:20 B.R.M.C.