Made by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: an Ethnography of Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hans-Peter Feldmann Named Winner

Guggenheim and AMO / Rem Koolhaas Announce Research Project Culminating in February 2020 Exhibition Countryside: Future of the World to Examine Radical Changes Transforming the Nonurban Landscape (NEW YORK, NY—November 29, 2017)—The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, architect and urbanist Rem Koolhaas, and AMO, the think tank of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), will collaborate on a project exploring radical changes in the countryside, the vast nonurban areas of Earth. The project extends work underway by AMO / Koolhaas and students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design and will culminate in a rotunda exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum in February 2020. Organized by Guggenheim Curator of Architecture and Digital Initiatives Troy Conrad Therrien, Founding Partner of OMA Rem Koolhaas, and AMO Director Samir Bantal, Countryside: Future of the World (working title) will present speculations about tomorrow through insights into the countryside of today. The exhibition will explore artificial intelligence and automation, the effects of genetic experimentation, political radicalization, mass and micro migration, large-scale territorial management, human-animal ecosystems, subsidies and tax incentives, the impact of the digital on the physical world, and other developments that are altering landscapes across the globe. “The Guggenheim has an appetite for experimentation and a founding belief in the transformative potential of art and architecture,” said Richard Armstrong, Director of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum and Foundation. -

Cladmag 2018 Issue 2

2018 ISSUE 2 CLADGLOBAL.COM mag @CLADGLOBAL FOR LEISURE ARCHITECTS, DESIGNERS, INVESTORS & DEVELOPERS INSIGHT PROFILE PERKINS+WILL’S DAVID Gabrielle COLLINS Bullock The good news STUDIO on diversity Keeping the legacy of its Martha founder alive Schwartz I became known for being controversial In my work, form follows fiction Ole Scheeren CREATORS OF WELLBEING AND RELAXATION Interior Design I Engineering Design IWŽŽůнdŚĞƌŵĂů/ŶƐƚĂůůĂƟŽŶI Maintenance Middle East + Asia UK + Europe ƐŝĂWĂĐŝĮĐ Barr + Wray Dubai Barr + Wray Barr + Wray Hong Kong T: + 971 4320 6440 T: + 44 141 882 9991 T: + 852 2214 9990 E: [email protected] E: [email protected] E: [email protected] www.barrandwray.com HEATED MARBLE LOUNGE CHAIRS By Fabio Alemanno Developed for the spa Perfected for the suite An exceptional collection of Regenerative warmth will pamper you whether handcrafted marble sculptures for in the Spa, the intimacy of the Suite or the Living room, making your rest unforgettable. hotel, spa and residential design With proven therapeutical benefits of long- Cut from a single block of flawless marble, wave infrared and advanced technical maturity, Fabio Alemanno infra-red heated lounge our products have become the first choice chairs are ergonomically shaped and for discerning clients around the world. unique in their design and structure. Unlimited choices of marble, exotic wood, leather, They combine wellness with design and technology and fabrics enable a perfect and seamless integration offering unparalleled comfort and amazing relaxation into any environment, offering architects and interior experiences while enhancing the state of well-being. designers endless possibilities for customisation. [email protected] www.fa-design.co.uk EDITOR’S LETTER Tree planting is one of the only ways to save the planet from #earthdeath Reforesting the world Climate scientists believe carbon capture through tree planting can buy us time to transition away from fossil fuels without wrecking the world’s economy. -

Building for Wellness: the Business Case

Building for Wellness THE BUSINESS CASE Building Healthy Places Initiative Building Healthy Places Initiative ULI Center for Capital Markets and Real Estate BuildingforWellness2014cover.indd 3 3/18/14 2:13 PM Building for Wellness THE BUSINESS CASE Project Director and Author Anita Kramer Primary Author Terry Lassar Contributing Authors Mark Federman Sara Hammerschmidt This project was made possible in part through the generous financial support of ULI Foundation Governor Bruce Johnson. ULI also wishes to acknowledge the Colorado Health Foundation for its support of the ULI Building Healthy Places Initiative. Building Healthy ULI Center for Capital Markets Places Initiative and Real Estate ACRONYMS HEPA—high-efficiency particulate absorption HOA—homeowners association Recommended bibliographic listing: HUD—U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Kramer, Anita, Terry Lassar, Mark Federman, and Sara Hammer- HVAC—heating, ventilation, and air conditioning schmidt. Building for Wellness: The Business Case. Washington, D.C.: LEED—Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Urban Land Institute, 2014. VOC—volatile organic compound ISBN: 978-0-87420-334-9 MEASUREMENTS © 2014 Urban Land Institute 1025 Thomas Jefferson Street, NW ac—acre Suite 500 West ha—hectare Washington, DC 20007-5201 km—kilometer All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of the whole or any part of mi—mile the contents without written permission of the copyright holder is sq ft—square foot prohibited. sq m—square meter 2 BUILDING FOR WELLNESS: THE BUSINESS CASE About the Urban Land Institute The mission of the Urban Land Institute is to provide • Sustaining a diverse global network of local prac- leadership in the responsible use of land and in tice and advisory efforts that address current and creating and sustaining thriving communities world- future challenges. -

Rem Koolhaas: an Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox

Lehigh University Lehigh Preserve Volume 16 - 2008 Lehigh Review 2008 Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation Daniel Fox Follow this and additional works at: http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16 Recommended Citation Fox, Daniel, "Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation" (2008). Volume 16 - 2008. Paper 8. http://preserve.lehigh.edu/cas-lehighreview-vol-16/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Lehigh Review at Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion in Volume 16 - 2008 by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rem Koolhaas: An Architecture of Innovation by Daniel Fox 22 he three Master Builders (as author Peter Blake refers to them) – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, and Frank Lloyd Wright – each Drown Hall (1908) had a considerable impact on the architec- In 1918, a severe outbreak ture of the twentieth century. These men of Spanish Influenza caused T Drown Hall to be taken over demonstrated innovation, adherence distinct effect on the human condi- by the army (they had been to principle, and a great respect for tion. It is Koolhaas’ focus on layering using Lehigh’s labs for architecture in their own distinc- programmatic elements that leads research during WWI) and tive ways. Although many other an environment of interaction (with turned into a hospital for Le- architects did indeed make a splash other individuals, the architecture, high students after St. Luke’s during the past one hundred years, and the exterior environment) which became overcrowded. Four the Master Builders not only had a transcends the eclectic creations students died while battling great impact on the architecture of of a man who seems to have been the century but also on the archi- influenced by each of the Master the flu in Drown. -

Finding Structural Solutions by Connecting Towers

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Finding Structural Solutions by Connecting Towers Authors: Andrew Luong, Director, Arup Michael Kwok, Director, Arup Subjects: Architectural/Design Structural Engineering Keywords: Cost Skybridges Publication Date: 2012 Original Publication: CTBUH Journal, 2012 Issue III Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Andrew Luong; Michael Kwok Research: China’s Unique Linked Towers Finding Structural Solutions by Connecting Towers A study of a number of linked high-rise towers in China finds designs anchored by innovative, unimposing structural solutions, which address issues of costs and buildability. More than simply making a dramatic visual statement, the links play an integral role in the buildings’ functions. Linked towers are still a rarity in the design of solving a number of problems and offering skyscrapers. Perhaps the most famous is the new opportunities in the design and usage of Andrew Luong Michael Kwok Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, but the buildings including: the linkage in the Petronas served as more Authors than just an architectural gesture. Structurally providing better masterplanning and Andrew Luong, Director Michael Kwok, Director there is little purpose to the skybridge, massing relationship in the site and to the Arup although the link it is an integral part of the neighboring architecture; 39/F–41/F Huaihai Plaza fire evacuation strategy and allows facilities to effective use of a limited and constrained 1045 Huaihai Road Shanghai 200031 be shared between the two towers over those site; China several levels, in addition to offering an increasing floor plate size; t: +86 21 6126 2888 observation deck, a popular attraction. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

To Read the Beijinger July/August 2017 Issue Online Now!

CHINESE COLD DISHES KO TAO LIAM GALLAGHER HANOI 2017/07-08 HOME IS WHERE THE HEART IS YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO HOUSE HUNTING IN BEIJING 1 JUL/AUG 2017 图书在版编目(CIP)数据 艺术北京 : 英文 / 《北京人系列丛书》编委会编著 旗下出版物 . -- 昆明 : 云南科技出版社, 2017.3 (北京人系列丛书) ISBN 978-7-5587-0464-2 Ⅰ. ①艺… Ⅱ. ①北… Ⅲ. ①北京-概况-英文 Ⅳ. ①K921 中国版本图书馆CIP数据核字(2017)第056249号 责任编辑:吴 琼 封面设计:Xixi 责任印刷:翟 苑 责任校对:叶水金 张彦艳 Since 2001 | 2001年创刊 thebeijinger.com A Publication of 广告代理: 北京爱见达广告有限公司 地址: 北京市朝阳区关东店北街核桃园30号 孚兴写字楼C座5层 Since 2006 | 2006年创刊 邮政编码: 100020 Beijing-kids.com 电话: 5779 8877 Advertising Hotline/广告热线: 5941 0368 /69 /72 /77 /78 /79 The Beijinger Managing Editor Margaux Schreurs Digital Content Managing Editor Tom Arnstein Editors Kyle Mullin, Tracy Wang Contributors Jeremiah Jenne, Andrew Killeen, Robynne Tindall True Run Media Founder & CEO Michael Wester Owner & Co-Founder Toni Ma Art Director Susu Luo Designer Xi Xi Production Manager Joey Guo Content Marketing Director Nimo Wanjau Head of Marketing & Communications Lareina Yang Events & Brand Manager Mu Yu Marketing Team Sharon Shang, Helen Liu, Nate Ren Head of HR & Admin Tobal Loyola Finance Manager Judy Zhao Accountant Vicky Cui Since 2012 | 2012年创刊 HR & Admin Officer Cao Zheng Jingkids.com Digital Development Director Alexandre Froger IT Support Specialist Yan Wen Photographer Uni You Sales Director Sheena Hu Account Managers Winter Liu, Wilson Barrie, Olesya Sedysheva, Renee Hu, Veronica Wu Sales Supporting Manager Gladys Tang Sales Coordinator Serena Du General inquiries: 5779 8877 Editorial inquiries: [email protected] Event -

Kris Provoost Belgium/China [email protected] - +8618616388046 Raffles City, Hangzhou

Photography Portfolio 2018 Architecture + Infrastructure Kris Provoost Belgium/China [email protected] - +8618616388046 Raffles City, Hangzhou Commission: UNStudio August 2018 Exterior and Aerial Photography Pudong Museum of Art, Shanghai Architect: Atelier Deshaus May 2018 Exterior Photography Gubei SOHO, Shanghai Architect: KPF May 2018 Construction Photography Harbin Grand Theater, Harbin Commision: MAD Architects July 2017 Exterior, Interior and Aerial Photography A11 Bridge, Bruges, Belgium Commission: Schlaich Bergermann Partner December 2017 Exterior Photography West Bund Bridge Zhangjiatang Commission: Schlaich Bergermann Partner September 2017 Construction and Aerial Photography Abu Dhabi Louvre Architect: Jean Nouvel December 2017 Exterior and Interior Photography Tianjin Binhai Library, Tianjin Commision: MVRDV December 2017 Exterior and Interior Photography TSMC Fab, Nanjing Commision: Kris Yao Artech July 2018 Exterior, Interior, Aerial Photography Beautified China Photo-essay capturing China flamboyant building boom DUO, Singapore Architect: Buro Ole Scheeren October 2017 Abstract Photography Kris Provoost: Publications: Kris Provoost is a Belgian born architect and photographer. Online Photography Portfolio: Kris’ work has been published around the world online and in Beautified China, photo-essay by Kris Provoost He is active in Asia designing and capturing buildings and https://www.krisprovoost.com print media. His Beautified China series is well received and has cities, to better understand the build environment. appeared on CNN, FastCoDesign, Fubiz, Abduzeedo, ArchDaily, Dezeen - April 30th, 2017 Online Videography Portfolio: Dezeen, Designboom, gooood, New York Times Magazine Kris Provoost photographs the most flamboyant architecture of https://www.youtube.com/donotsettle Spain, as well as in print magazines China Life, ArchiKultura, China’s building boom After graduating in 2010 with a Master in Architecture, he Experimenta, That’s Mag and others. -

WARCHITECTURE Hinted at the Day Before

IIAS_NL#39 09-12-2005 17:03 Pagina 20 > Rem Koolhaas IIAS annual lecture SKYSCRAPERS AND SLEDGEHAMMERS The 10th IIAS annual lecture was delivered in Amsterdam on 17 November by world-famous Dutch architect and Harvard professor ...THE DAY AFTER Rem Koolhaas. Co-founder and partner of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and initiator of AMO, its think-tank/mirror Zheng Shiling from Shanghai, Xing Ruan from Sydney and Anne- image, Koolhaas’ projects include de Kunsthal in Rotterdam, Guggenheim Las Vegas, a Prada boutique in Soho, Casa da Musica in Marie Broudehoux from Quebec City were Koolhaas’ discussants Porto and most spectacularly, the new CCTV headquarters in Beijing. His writings range from his Delirious New York, a retroactive following the lecture. To give our guests a chance to meet their manifesto (1978) to his massive 1,500 page S,M,L,XL (1995), several projects supervised at Harvard including Great Leap Forward Dutch and Flemish brothers in arms, IIAS organized a meeting (2002) and Harvard Design School Guide to Shopping (2002) to his most recent volume between a book and a magazine, Content at the Netherlands Architectural Institute in Rotterdam the fol- (2005). On these pages of the IIAS newsletter, itself a strange animal between an academic journal and newspaper, we explore why lowing day. Bearing the title (Per)forming Culture; Architecture and Koolhaas in his last book invites us to Go East; why he has a long-time fascination with the Asian city; why the Metabolists have Life in the Chinese Megalopolis, specialists of contemporary Chi- always intrigued him; why OMA has developed an interest in preserving ancient Beijing; and, perhaps most importantly, why he nese urban change – including scholars of architectural theory, thinks architecture is so closely connected to ideology. -

Büro Ole Scheeren Unveils Design for Guardian Art Center in Beijing

PRESS RELEASE March 9, 2015 A fusion of time and a synthesis of China's rich cultural history: Büro Ole Scheeren unveils design for Guardian Art Center in Beijing Located in close proximity to the Forbidden City, construction is underway on the new headquarters of China’s oldest art auction house. Embedded in the historic fabric of central Beijing, the building will form a new hybrid institution between museum, event space, and cultural lifestyle center. Ole Scheeren’s design for the Guardian Art Center carefully inscribes the building into the surrounding context, in a sensitive architectural interpretation that fuses history and tradition with a contemporary vision for the future of a cultural art space. The ‘pixelated’ volumes of the lower portion of the building subtly refer to the adjacent historic urban fabric, echoing the grain, color and intricate scale of Beijing’s hutongs, while the upper portion of the building responds to the larger scale of the surrounding contemporary city. This floating ‘ring’ forms an inner courtyard to the building and further resonates with the prevalent typology of the courtyard houses in Beijing. “The Art Center will be a tangible link between past, present, and future. It celebrates history and tradition while also representing an important social and civic amenity for the capital” says China Guardian’s Chairman and Founder, Chen Dongsheng. “The design of the building shares its qualities with those of Guardian. It is profound, simple, and clean, and exudes a sense of stability and trustworthiness” adds Mr. Chen. “Ole Scheeren’s work is rooted in culture and history; it reflects the culture of the site and the culture and customs of the Chinese people. -

China's Master Planning System in Transition Case Study on Beijing

Gu Chaolin, Yuan Xiaohui and Guo Jing, China’s master planning system in transition: case study of Beijing, 46th ISOCARP Congress 2010 China’s master planning system in transition Case study on Beijing Gu Chaolin Yuan Xiaohui Guo Jing 1. Introduction Ever since China reformed and opened up to the world in 1978, there were immense changes taken place in structure and system framework of society, economy and space. The service industry has entered the fast development track and the economic structure is speedily adjusting. Millions of farmers left their land to look for new development. In this period, industrialization and urbanization kept pushing forward. Thus, the conflicts between rural and urban development deteriorated and social migration is increasing. The largest dualistic economy entity in the world is changing. During this period, resource consumption increases rapidly in volume and environmental pressure continues to increase. In fact, China’s urban planning system play an important role for its development and growth as well as resource and environmental problems. This paper will discuss the great changes of the China’s urban planning system and have a Beijing case study during that time. In general, Urban planning in China first 30 years used the former Soviet Union urban planning model according to the planned economy system. Urban planning is implementation in space of the state economic development plans. The second 30 years exploring national conditions of the socialist market economic system in urban planning. Traditional urban planning system is broken and the new planning system also can not copy urban planning system from the European market economy countries. -

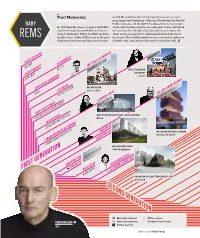

First Generation Second Generation

by Paul Makovsky world. Not only has the firm designed some of our era’s most important buildings—Maison à Bordeaux, the Seattle BABY Public Library, and the CCTV headquarters, to name just In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia a few—but its famous hothouse atmosphere has cultivated and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon VriesenVriesen-- the talents of hundreds of gifted architects. Look at the dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan chart on these pages: it is a distinguished architectural REMS Architecture. Today OMA is one of the most fraternity. These OMA grads have now created an influence influential architectural practices in the all their own, and they are the ones to watch in 2011. P ZAHA HADID RIENTS DIJKSTRA EDZO BINDELS MAXWAN MATTHIAS SAUERBRUCH WEST 8 SAUERBRUCH HUTTON EVELYN GRACE ACADEMY CHRISTIAN RAPP London RAPP + RAPP CHRISTOPHE CORNUBERT M9 MUSEUM LUC REUSE Venice, Italy WILLEM JAN NEUTELINGS PUSH EVR ARCHITECTEN NEUTELINGS RIEDIJK LAURINDA SPEAR ARQUITECTONICA KEES CHRISTIAANSE SOUTH DADE CULTURAL ARTS CENTER KGAP ARCHITECTS AND PLANNERS Miami YUSHI UEHARA ZERODEGREE ARCHITECTURE MVRDV WINY MAAS MUSEUM AAN DE STROOM Antwerp, Belgium RUURD ROORDA KLAAS KINGMA JACOB VAN RIJS KINGMA ROORDA ARCHITECTEN BALANCING BARN Suffolk, England FOA WW ARCHITECTURE SARAH WHITING FARSHID MOUSSAVI RON WITTE FIRST GENERATION MIKE GUYER ALEJANDRO ZAERA POLO GIGON GUYER MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART Cleveland SECOND GENERATION Married/partnered Office closed REM KOOLHAAS P Divorced/separated P Pritzker Prize laureate OMA Former partner Illustration by Nikki Chung REM_Baby REMS_01_11_rev.indd 1 12/16/10 7:27:54 AM BABY REMS by Paul Makovsky In 1975 Rem Koolhaas, together with Elia and Zoe Zenghelis and Madelon Vriesen- dorp, founded the Office for Metropolitan Architecture.