UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orthography of Early Chinese Writing: Evidence from Newly Excavated Manuscripts

IMRE GALAMBOS ORTHOGRAPHY OF EARLY CHINESE WRITING: EVIDENCE FROM NEWLY EXCAVATED MANUSCRIPTS BUDAPEST MONOGRAPHS IN EAST ASIAN STUDIES SERIES EDITOR: IMRE HAMAR IMRE GALAMBOS ORTHOGRAPHY OF EARLY CHINESE WRITING: EVIDENCE FROM NEWLY EXCAVATED MANUSCRIPTS DEPARTMENT OF EAST ASIAN STUDIES, EÖTVÖS LORÁND UNIVERSITY BUDAPEST 2006 The present volume was published with the support of the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation. © Imre Galambos, 2006 ISBN 963 463 811 2 ISSN 1787-7482 Responsible for the edition: Imre Hamar Megjelent a Balassi Kiadó gondozásában (???) A nyomdai munkálatokat (???)a Dabas-Jegyzet Kft. végezte Felelős vezető Marosi Györgyné ügyvezető igazgató CONTENTS Acknowledgements ................................................................................................. vii Introduction ............................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER ONE FORMER UNDERSTANDINGS ..................................................................................... 11 1.1 Traditional views ........................................................................................... 12 1.1.1 Ganlu Zishu ........................................................................................ 13 1.1.2 Hanjian .............................................................................................. 15 1.2 Modern views ................................................................................................ 20 1.2.1 Noel Barnard ..................................................................................... -

The Discovery of Chinese Logic Modern Chinese Philosophy

The Discovery of Chinese Logic Modern Chinese Philosophy Edited by John Makeham, Australian National University VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.nl/mcp. The Discovery of Chinese Logic By Joachim Kurtz LEIDEN • BOSTON 2011 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kurtz, Joachim. The discovery of Chinese logic / by Joachim Kurtz. p. cm. — (Modern Chinese philosophy, ISSN 1875-9386 ; v. 1) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17338-5 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Logic—China—History. I. Title. II. Series. BC39.5.C47K87 2011 160.951—dc23 2011018902 ISSN 1875-9386 ISBN 978 90 04 17338 5 Copyright 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. CONTENTS List of Illustrations ...................................................................... vii List of Tables ............................................................................. -

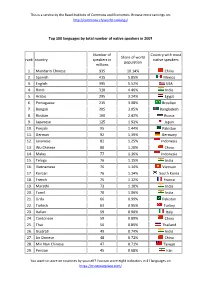

Top 100 Languages by Total Number of Native Speakers in 2007 Rank

This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. Browse more rankings on: http://commons.ch/world-rankings/ Top 100 languages by total number of native speakers in 2007 Number of Country with most Share of world rank country speakers in native speakers population millions 1. Mandarin Chinese 935 10.14% China 2. Spanish 415 5.85% Mexico 3. English 395 5.52% USA 4. Hindi 310 4.46% India 5. Arabic 295 3.24% Egypt 6. Portuguese 215 3.08% Brasilien 7. Bengali 205 3.05% Bangladesh 8. Russian 160 2.42% Russia 9. Japanese 125 1.92% Japan 10. Punjabi 95 1.44% Pakistan 11. German 92 1.39% Germany 12. Javanese 82 1.25% Indonesia 13. Wu Chinese 80 1.20% China 14. Malay 77 1.16% Indonesia 15. Telugu 76 1.15% India 16. Vietnamese 76 1.14% Vietnam 17. Korean 76 1.14% South Korea 18. French 75 1.12% France 19. Marathi 73 1.10% India 20. Tamil 70 1.06% India 21. Urdu 66 0.99% Pakistan 22. Turkish 63 0.95% Turkey 23. Italian 59 0.90% Italy 24. Cantonese 59 0.89% China 25. Thai 56 0.85% Thailand 26. Gujarati 49 0.74% India 27. Jin Chinese 48 0.72% China 28. Min Nan Chinese 47 0.71% Taiwan 29. Persian 45 0.68% Iran You want to score on countries by yourself? You can score eight indicators in 41 languages on https://trustyourplace.com/ This is a service by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics. -

Tibetan Written Images : a Study of Imagery in the Writings of Dhondup

Tibetan Written Images A STUDY OF IMAGERY IN THE WRITINGS OF DHONDUP GYAL Riika J. Virtanen Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 23rd of September, 2011 at 12 o'clock Publications of the Institute for Asian and African Studies 13 ISBN 978-952-10-7133-1 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-7134-8 (PDF) ISSN 1458-5359 http://ethesis.helsinki.fi Unigrafia Helsinki 2011 2 ABSTRACT Dhondup Gyal (Don grub rgyal, 1953 - 1985) was a Tibetan writer from Amdo (Qinghai, People's Republic of China). He wrote several prose works, poems, scholarly writings and other works which have been later on collected together into The Collected Works of Dhondup Gyal, in six volumes. He had a remarkable influence on the development of modern Tibetan literature in the 1980s. Exam- ining his works, which are characterized by rich imagery, it is possible to notice a transition from traditional to modern ways of literary expression. Imagery is found in both the poems and prose works of Dhondup Gyal. Nature imagery is especially prominent and his writings contain images of flowers and plants, animals, water, wind and clouds, the heavenly bodies and other en- vironmental elements. Also there are images of parts of the body and material and cultural images. To analyse the images, most of which are metaphors and similes, the use of the cognitive theory of metaphor provides a good framework for mak- ing comparisons with images in traditional Tibetan literature and also some images in Chinese, Indian and Western literary works. -

The Old Master

INTRODUCTION Four main characteristics distinguish this book from other translations of Laozi. First, the base of my translation is the oldest existing edition of Laozi. It was excavated in 1973 from a tomb located in Mawangdui, the city of Changsha, Hunan Province of China, and is usually referred to as Text A of the Mawangdui Laozi because it is the older of the two texts of Laozi unearthed from it.1 Two facts prove that the text was written before 202 bce, when the first emperor of the Han dynasty began to rule over the entire China: it does not follow the naming taboo of the Han dynasty;2 its handwriting style is close to the seal script that was prevalent in the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). Second, I have incorporated the recent archaeological discovery of Laozi-related documents, disentombed in 1993 in Jishan District’s tomb complex in the village of Guodian, near the city of Jingmen, Hubei Province of China. These documents include three bundles of bamboo slips written in the Chu script and contain passages related to the extant Laozi.3 Third, I have made extensive use of old commentaries on Laozi to provide the most comprehensive interpretations possible of each passage. Finally, I have examined myriad Chinese classic texts that are closely associated with the formation of Laozi, such as Zhuangzi, Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr. Lü), Han Feizi, and Huainanzi, to understand the intellectual and historical context of Laozi’s ideas. In addition to these characteristics, this book introduces several new interpretations of Laozi. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:34:09AM Via Free Access Bruce Rusk: Old Scripts, New Actors 69

EASTM 26 (2007): 68-116 Old Scripts, New Actors: European Encounters with Chinese Writing, 1550-1700* Bruce Rusk [Bruce Rusk is Assistant Professor of Chinese Literature in the Department of Asian Studies at Cornell University. From 2004 to 2006 he was Mellon Humani- ties Fellow in the Asian Languages Department at Stanford University. His dis- sertation was entitled “The Rogue Classicist: Feng Fang and his Forgeries” (UCLA, 2004) and his article “Not Written in Stone: Ming Readers of the Great Learning and the Impact of Forgery” appeared in The Harvard Journal of Asi- atic Studies 66.1 (June 2006).] * * * But if a savage or a moon-man came And found a page, a furrowed runic field, And curiously studied line and frame: How strange would be the world that they revealed. A magic gallery of oddities. He would see A and B as man and beast, As moving tongues or arms or legs or eyes, Now slow, now rushing, all constraint released, Like prints of ravens’ feet upon the snow. — Herman Hesse1 Visitors to the Far East from early modern Europe reported many marvels, among them a writing system unlike any familiar alphabetic script. That the in- habitants of Cathay “in a single character make several letters that comprise one * My thanks to all those who provided feedback on previous versions of this paper, especially the workshop commentator, Anthony Grafton, and Liam Brockey, Benjamin Elman, and Martin Heijdra as well as to the Humanities Fellows at Stanford. I thank the two anonymous readers, whose thoughtful comments were invaluable in the revision of this essay. -

47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47

Vol 47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47 PLATEAU NARRATIVES 2017 Vol 47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47 E-MAIL: [email protected] HARD COPY: www.lulu.com/asianhp ONLINE: https://goo.gl/JycnYT ISSN (print): 1835-7741 ISSN (electronic): 1925-6329 Library of Congress Control Number: 2008944256 CALL NUMBER: DS1.A4739 SUBJECTS: Uplands-Asia-Periodicals, Tibet, Plateau of-Periodicals All artwork contained herein is subject to a Creative Commons, Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. You are free to quote, copy, and distribute these works for non-commercial purposes so long as appropriate attribution is given. See https://goo.gl/nq06vg for more information. CITATION: Plateau Narratives 2017. 2017. Asian Highlands Perspectives 47. COVERS: Taken at a monastery in Rnga ba bod rigs dang chang rigs rang skyong khul (Aba zangzu qiangzu བབོདརིགསདངཆངརིགསརངོངལ zizhizhou 阿坝藏族羌族自治州 'Rnga ba Tibetan and Qiang Autonomous Prefecture'), Sichuan 四川 Province, China (2017, 'Jam dbyangs skyabs ). འཇམདངསབས 2 Vol 47 2017 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES 2017 Vol 47 ASIAN HIGHLANDS PERSPECTIVES Asian Highlands Perspectives (AHP ) is a trans-disciplinary journal focusing on the Tibetan Plateau and surrounding regions, including the Southeast Asian Massif, Himalayan Massif, the Extended Eastern Himalayas, the Mongolian Plateau, and other contiguous areas. The editors believe that cross-regional commonalities in history, culture, language, and socio-political context invite investigations of an interdisciplinary nature not served by current academic forums. AHP contributes to the regional research agendas of Sinologists, Tibetologists, Mongolists, and South and Southeast Asianists, while also forwarding theoretical discourse on grounded theory, interdisciplinary studies, and collaborative scholarship. AHP publishes occasional monographs and essay collections both in hardcopy (ISSN 1835-7741) and online (ISSN 1925-6329). -

Bibliography

Bibliography An, Qi 安琪 et al., eds. 2003. Zhongjiandai Shi 中间代诗 (Mid-generation poetry). Fuzhou: Haixia wenyi chubanshe. Artisan of Flowery Rocks 花岩匠人. “Net Servers.” In Low Poetry Tide <http://my.ziqu.com/bbs/666023/>. Accessed November 11, 2006. Auden, W. H. 1975a. “American Poetry.” In The Dyer’s Hand and Other Essays, 354–368. London: Faber and Faber. ———. 1975b. “Robert Frost.” In The Dyer’s Hand and Other Essays, 337–353. London: Faber and Faber. Ballard, J. G. 1970. The Atrocity Exhibition. London: Granda Books. Barlow, Tani E., ed. 1993. Gender Politics in Modern China: Writing and Feminism. Durham: Duke University Press. ———. 1994. “Politics and Protocols of Funü: (Un)Making National Woman.” In Gilmartin 1994: 339–359. Barmé, Geremie, and John Minford, eds. 1986. Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience. Hong Kong: Far Eastern Economic Review. Baudelaire, Charles. 1993. “Le Cygne” (The Swan). In James McGowan, tr., The Flowers of Evil. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 172–177. Bei, Dao 北島. 1991. Old Snow. Bonnie S. McDougall and Chen Maiping, trs. New York: New Directions. Benjamin, Walter. 1979. One-Way Street and Other Writings. London: New Left Books. Bing, Xin 冰心 (Xie Wanying 謝婉瑩). 1923. Fanxing 繁星 (Myriad stars). Shanghai: Commercial Press. ———. 1931. Chunshui 春水 (Spring waters), reprint. Shanghai: Beixin shuju. ———. 1949. Bing Xin shiji 冰心詩集 (Collected works of Bing Xin). Reprint, Shanghai: Kaiming shudian. Booth, Allyson. 1996. Postcards from the Trenches: Negotiating the Space between Modernism and the First World War. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Borges, Jorge Luis. 1999. “The Argentine Writer and Tradition.” In Eliot Weinberger, ed., Selected Non-Fictions, 420–427. -

Downloaded 4.0 License

Return to an Inner Utopia 119 Chapter 4 Return to an Inner Utopia In what was to become a celebrated act in Chinese literary history, Su Shi be- gan systematically composing “matching Tao” (he Tao 和陶) poems in the spring of 1095, during his period of exile in Huizhou. This project of 109 poems was completed when he was further exiled to Danzhou. It was issued in four fascicles, shortly after his return to the mainland in 1100.1 Inspired by and fol- lowing the rhyming patterns of the poetry of Tao Qian, these poems contrib- uted to the making (and remaking) of the images of both poets, as well as a return to simplicity in Chinese lyrical aesthetics.2 Thus far, scholarship has focused on the significance of Su Shi’s agency in Tao Qian’s canonisation. His image was transformed through Su’s criticism and emulation: Tao came to be viewed as a spontaneous Man of the Way and not just an eccentric medieval recluse and hearty drinker.3 In other words, Tao Qian’s ‘spontaneity’ was only created retrospectively in lament over its loss. The unattainability of the ideal is part and parcel of its worth. In this chapter, I will further examine what Su Shi’s practice meant for Su Shi himself. I argue that Su Shi’s active transformation of and identification with Tao Qian’s image were driven by the purpose of overcoming the tyranny of despair, deprivation and mortality. The apparent serenity of the “matching Tao” poems was therefore fundamentally paradoxical, a result of self-persua- sion. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee -

China Genetics

Stratification in the peopling of China: how far does the linguistic evidence match genetics and archaeology? Paper for the Symposium : Human migrations in continental East Asia and Taiwan: genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence Geneva June 10-13, 2004. Université de Genève [DRAFT CIRCULATED FOR COMMENT] Roger Blench Mallam Dendo 8, Guest Road Cambridge CB1 2AL United Kingdom Voice/Answerphone/Fax. 0044-(0)1223-560687 E-mail [email protected] http://homepage.ntlworld.com/roger_blench/RBOP.htm Cambridge, Sunday, 06 June 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS FIGURES.......................................................................................................................................................... i 1. Introduction................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.1 The problem: linking linguistics, archaeology and genetics ................................................................... 3 1.2 Methodological issues............................................................................................................................. 3 2. The linguistic pattern of present-day China............................................................................................. 5 2.1 General .................................................................................................................................................... 5 2.2 Sino-Tibetan........................................................................................................................................... -

The Zuo Zhuan Revisited*

《中國文化研究所學報》 Journal of Chinese Studies No. 49 - 2009 REVIEW ARTICLE Rethinking the Origins of Chinese Historiography: The Zuo Zhuan Revisited* Yuri Pines The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The Readability of the Past in Early Chinese Historiography. By Wai-yee Li. Cam- bridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Asia Center, 2007. Pp. xxii + 449. $49.50/£36.95. The Readability of the Past in Early Chinese Historiography is a most welcome addition to the growing number of Western-language studies on the Zuo zhuan 左傳. Wai-yee Li’s eloquent book is the fruit of impeccable scholarship. It puts forward an abundance of insightful and highly original analyses and fully demonstrates the advantages of the skilful application of literary techniques to early Chinese historiography. This work is sure to become an indispensable tool for any scholar interested in the Zuo zhuan or early Chinese historiography in general. Furthermore, many of Li’s observations are likely to encourage further in-depth research on this foundational text. To illustrate the importance of The Readability of the Past, it is worth high- lighting its position vis-à-vis prior Western-language studies on the Zuo zhuan. Oddly enough, despite its standing as the largest pre-imperial text, despite its canonical status, and despite its position as a fountainhead of Chinese historiography—the Zuo zhuan was virtually neglected by mainstream Occidental Sinology throughout the twentieth century. Notwithstanding the pioneering (and highly controversial) study of Bernhard Karlgren, “On the Authenticity and Nature of the Tso Chuan,” which was published back in 1928, the Zuo zhuan rarely stood at the focus of scholarly endeavour.1 The only Western-language publication dedicated entirely to * This review article was prepared with the support by the Israel Science Foundation (grant No.