Deutsche Kinemathek—Hans G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Includes Our Main Attractions and Special

Princeton Garden Theatre Previews93G SEPTEMBER - DECEMBER 2015 Benedict Cumberbatch in rehearsal for HAMLET INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS P RINCETONG ARDENT HEATRE.ORG 609 279 1999 Welcome to the nonprofit Princeton Garden Theatre The Garden Theatre is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Our management team. ADMISSION Nonprofit Renew Theaters joined the Princeton community as the new operator of the Garden Theatre in July of 2014. We General ............................................................$11.00 also run three golden-age movie theaters in Pennsylvania – the Members ...........................................................$6.00 County Theater in Doylestown, the Ambler Theater in Ambler, and Seniors (62+) & University Staff .........................$9.00 the Hiway Theater in Jenkintown. We are committed to excellent Students . ..........................................................$8.00 programming and to meaningful community outreach. Matinees Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 How can you support Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$8.00 the Garden Theatre? PRINCETON GARDEN THEATRE Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$7.00 Be a member. MEMBER Affiliated Theater Members* .............................$6.00 Become a member of the non- MEMBER You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. profit Garden Theatre and show The above ticket prices are subject to change. your support for good films and a cultural landmark. See back panel for a membership form or join online. Your financial support is tax-deductible. *Affiliated Theater Members Be a sponsor. All members of our theater are entitled to members tickets at all Receive prominent recognition for your business in exchange “Renew Theaters” (Ambler, County, Garden, and Hiway), as well for helping our nonprofit theater. Recognition comes in a variety as at participating “Art House Theaters” nationwide. -

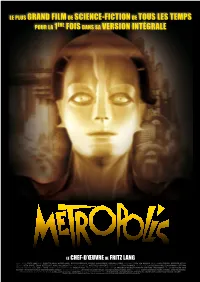

Dp-Metropolis-Version-Longue.Pdf

LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA 1ÈRE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTÉGRALE LE CHEf-d’œuvrE DE FRITZ LANG UN FILM DE FRITZ LANG AVEC BRIGITTE HELM, ALFRED ABEL, GUSTAV FRÖHLICH, RUDOLF KLEIN-ROGGE, HEINRICH GORGE SCÉNARIO THEA VON HARBOU PHOTO KARL FREUND, GÜNTHER RITTAU DÉCORS OTTO HUNTE, ERICH KETTELHUT, KARL VOLLBRECHT MUSIQUE ORIGINALE GOTTFRIED HUPPERTZ PRODUIT PAR ERICH POMMER. UN FILM DE LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG EN COOPÉRATION AVEC ZDF ET ARTE. VENTES INTERNATIONALES TRANSIT FILM. RESTAURATION EFFECTUÉE PAR LA FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG, WIESBADEN AVEC LA DEUTSCHE KINE MATHEK – MUSEUM FÜR FILM UND FERNSEHEN, BERLIN EN COOPÉRATION AVEC LE MUSEO DEL CINE PABLO C. DUCROS HICKEN, BUENOS AIRES. ÉDITORIAL MARTIN KOERBER, FRANK STROBEL, ANKE WILKENING. RESTAURATION DIGITAle de l’imAGE ALPHA-OMEGA DIGITAL, MÜNCHEN. MUSIQUE INTERPRÉTÉE PAR LE RUNDFUNK-SINFONIEORCHESTER BERLIN. ORCHESTRE CONDUIT PAR FRANK STROBEL. © METROPOLIS, FRITZ LANG, 1927 © FRIEDRICH-WILHELM-MURNAU-STIFTUNG / SCULPTURE DU ROBOT MARIA PAR WALTER SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF © BERTINA SCHULZE-MITTENDORFF MK2 et TRANSIT FILMS présentent LE CHEF-D’œuvre DE FRITZ LANG LE PLUS GRAND FILM DE SCIENCE-FICTION DE TOUS LES TEMPS POUR LA PREMIERE FOIS DANS SA VERSION INTEGRALE Inscrit au registre Mémoire du Monde de l’Unesco 150 minutes (durée d’origine) - format 1.37 - son Dolby SR - noir et blanc - Allemagne - 1927 SORTIE EN SALLES LE 19 OCTOBRE 2011 Distribution Presse MK2 Diffusion Monica Donati et Anne-Charlotte Gilard 55 rue Traversière 55 rue Traversière 75012 Paris 75012 Paris [email protected] [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 67 30 80 Tél. -

Saudades Do Futuro: O Cinema De Ficção Científica Como Expressão Do Imaginário Social Sobre O Devir

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS DEPARTAMENTO DE SOCIOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM SOCIOLOGIA TESE DE DOUTORADO SAUDADES DO FUTURO: O CINEMA DE FICÇÃO CIENTÍFICA COMO EXPRESSÃO DO IMAGINÁRIO SOCIAL SOBRE O DEVIR Autora: Alice Fátima Martins Orientador: Prof. João Gabriel L. C. Teixeira (UnB) Banca: Prof. Paulo Menezes (USP) Prof. Julio Cabrera (UnB) Profª. Fernanda Sobral (SOL/UnB) Prof. Brasilmar Ferreira Nunes (SOL/UnB) Suplentes: Profª. Lourdes Bandeira (SOL/UnB) Prof. Roberto Moreira (SOL/UnB) Profª. Angelica Madeira (SOL/UnB) Profª. Ana Vicentini (CEPPAC/UnB) Profª. Mariza Veloso (SOL/UnB) 2 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao CNPq, pelo apoio financeiro a este trabalho; Ao Prof. João Gabriel L. C. Teixeira, orientador desta tese, companheiro inestimável nesse caminho acadêmico; Aos professores doutores que aceitaram o convite para compor esta banca: Prof. Paulo Menezes, Prof. Julio Cabrera, Profª. Fernanda Sobral, Prof. Brasilmar Ferreira Nunes; Aos suplentes da banca: Profª. Lourdes Bandeira, Prof. Roberto Moreira, Profª. Angélica Madeira, Profª. Ana Vicentini, Profª. Mariza Veloso; Ao Prof. Sergio Paulo Rouanet, que compôs a banca de qualificação, e cujas sugestões foram incorporadas à pesquisa, além das preciosas interlocuções ao longo do percurso; Aos Professores Eurico A. Gonzalez C. Dos Santos, Sadi Dal Rosso e Bárbara Freitag, com quem tive a oportunidade e o privilégio de dialogar, nas disciplinas cursadas; À equipe da Secretaria do Departamento de Sociologia/SOL/UnB, aqui representados na pessoa do Sr. Evaldo A. Amorim; À Professora Iria Brzezinski, pelo incentivo científico-acadêmico, sempre confraterno; À Professora Maria F. de Rezende e Fusari, pelos sábios ensinamentos, quanta saudade... Ao Professor Otávio Ianni, pelas sábias sugestões, incorporadas ao trabalho; Ao Professor J. -

Catalogo Giornate Del Cinema Muto 2011

Clara Bow in Mantrap, Victor Fleming, 1926. (Library of Congress) Merna Kennedy, Charles Chaplin in The Circus, 1928. (Roy Export S.A.S) Sommario / Contents 3 Presentazione / Introduction 31 Shostakovich & FEKS 6 Premio Jean Mitry / The Jean Mitry Award 94 Cinema italiano: rarità e ritrovamenti Italy: Retrospect and Discovery 7 In ricordo di Jonathan Dennis The Jonathan Dennis Memorial Lecture 71 Cinema georgiano / Georgian Cinema 9 The 2011 Pordenone Masterclasses 83 Kertész prima di Curtiz / Kertész before Curtiz 0 1 Collegium 2011 99 National Film Preservation Foundation Tesori western / Treasures of the West 12 La collezione Davide Turconi The Davide Turconi Collection 109 La corsa al Polo / The Race to the Pole 7 1 Eventi musicali / Musical Events 119 Il canone rivisitato / The Canon Revisited Novyi Vavilon A colpi di note / Striking a New Note 513 Cinema delle origini / Early Cinema SpilimBrass play Chaplin Le voyage dans la lune; The Soldier’s Courtship El Dorado The Corrick Collection; Thanhouser Shinel 155 Pionieri del cinema d’animazione giapponese An Audience with Jean Darling The Birth of Anime: Pioneers of Japanese Animation The Circus The Wind 165 Disney’s Laugh-O-grams 179 Riscoperte e restauri / Rediscoveries and Restorations The White Shadow; The Divine Woman The Canadian; Diepte; The Indian Woman’s Pluck The Little Minister; Das Rätsel von Bangalor Rosalie fait du sabotage; Spreewaldmädel Tonaufnahmen Berglund Italianamerican: Santa Lucia Luntana, Movie Actor I pericoli del cinema / Perils of the Pictures 195 Ritratti / Portraits 201 Muti del XXI secolo / 21st Century Silents 620 Indice dei titoli / Film Title Index Introduzioni e note di / Introductions and programme notes by Peter Bagrov Otto Kylmälä Aldo Bernardini Leslie Anne Lewis Ivo Blom Antonello Mazzucco Lenny Borger Patrick McCarthy Neil Brand Annette Melville Geoff Brown Russell Merritt Kevin Brownlow Maud Nelissen Günter A. -

Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette

www.ssoar.info Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933) Kester, Bernadette Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Monographie / monograph Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Kester, B. (2002). Film Front Weimar: Representations of the First World War in German Films from the Weimar Period (1919-1933). (Film Culture in Transition). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-317059 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de * pb ‘Film Front Weimar’ 30-10-2002 14:10 Pagina 1 The Weimar Republic is widely regarded as a pre- cursor to the Nazi era and as a period in which jazz, achitecture and expressionist films all contributed to FILM FRONT WEIMAR BERNADETTE KESTER a cultural flourishing. The so-called Golden Twenties FFILMILM FILM however was also a decade in which Germany had to deal with the aftermath of the First World War. Film CULTURE CULTURE Front Weimar shows how Germany tried to reconcile IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION the horrendous experiences of the war through the war films made between 1919 and 1933. -

Zeughauskino: Gretchen Und Germania

GRETCHEN UND GERMANIA HOMMAGE AN HENNY PORTEN Wie kaum eine andere deutsche Schauspielerin hat Henny Porten (1890 – 1960) zwischen 1910 und 1933 das populäre Bild der Frau in Deutschland verkörpert und geprägt. Bewunderer hatte sie in allen Bevölkerungsschichten: Soldatenräte ließen sie in den November- kämpfen 1918 hochleben; Reichstagspräsident Ebert besuchte ihre Dreharbeiten; und bei ihren Filmpremieren erlebten die Innenstädte Massenaufläufe. Ironisch und ernsthaft augenzwinkernd schlug 1922 der Literat Kurt Pinthus im linksliberalen Tagebuch vor: »Man mache Henny Porten zum Reichspräsidenten! Hier ist eine Gestalt, die in Deutschland volkstümlicher ist als der alte Fritz, als der olym- pische Goethe es je waren und sein konnten... Hier ist eine schöne Frau, die als Vereinigung von Gretchen und Germania von diesem Volke selbst als Idealbild eben dieses Volkes aufgerichtet wurde«. Bereits seit 1906 war die junge Porten in Dutzenden von Tonbildern aufgetreten, in nachgestellten kurzen Opernszenen, zu denen im Kino der entsprechende Musikpart aus dem Grammophon erklang. Mit großen Posen und Affektdarstellungen eiferten die Darsteller dieser frühen, oft nur eine Minute langen Filme den bekannten Mimen der Hoftheater nach. Bekannte, zur Ikone geronnene Darstel- lungsklischees großer Gefühle nahm die junge Filmschauspielerin auf und formte daraus ein filmspezifisches Vokabular stummen Spiels, eindringlicher Gesten und Blicke. Portens Gebärdensprache betont die vereinzelte Geste und isoliert Bedeutung, die nur in Gip- felmomenten beschleunigt, ansonsten aber ausgespielt oder ver- langsamt wird. Portens häufig wiederkehrendes Darstellungsfeld – schicksalsschwe- rer Kampf und mit Demut getragenes Leid – wird während des Ers- ten Weltkriegs Realität vieler Frauen. Henny Porten, die ihren ersten Mann in diesem Krieg verlor, erschien in ihren Figuren wie in ihrem Starleben gerade in den 1910er Jahren als ein Spiegelbild der deut- Die Heimkehr des Odysseus GRETCHEN UND GERMANIA 31 GRETCHEN UND GERMANIA schen Frauenseele. -

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy in the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946

The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger 1939-1946 Valerie Wilson University College London PhD May 2001 ProQuest Number: U642581 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U642581 Published by ProQuest LLC(2015). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 The Representation of Reality and Fantasy In the Films of Powell and Pressburger: 1939-1946 This thesis will examine the films planned or made by Powell and Pressburger in this period, with these aims: to demonstrate the way the contemporary realities of wartime Britain (political, social, cultural, economic) are represented in these films, and how the realities of British history (together with information supplied by the Ministry of Information and other government ministries) form the basis of much of their propaganda. to chart the changes in the stylistic combination of realism, naturalism, expressionism and surrealism, to show that all of these films are neither purely realist nor seamless products of artifice but carefully constructed narratives which use fantasy genres (spy stories, rural myths, futuristic utopias, dreams and hallucinations) to convey their message. -

Weimar International

Weimar International Stummfilm ohne Grenzen aus Berlin und Brandenburg, 1918-1929 Eine Filmreihe von Philipp Stiasny und Frederik Lang in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Zeughaus- kino (Berlin). Gefördert durch den Hauptstadtkulturfonds. Unterstützt von der Friedrich- Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung (Wiesbaden) und CineGraph Babelsberg e.V. 4.11.2018 Am Flügel: Stephan Graf von Bothmer Zigano, der Brigant von Monte Diavolo (Deutschland / Frankreich 1925, Regie: Harry Piel) Foto: Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin Zigano, der Brigant von Monte Diavolo Deutschland/Frankreich 1925 / Regie: Harry Piel, Gérard Bourgeois (?) / Buch: Henrik Galeen, Harry Piel / Kamera: Georg Muschner, Gotthardt Wolf / Bauten: Gustav A. Knauer / Darsteller: Harry Piel (Benito), Dary Holm (Beatrice), Raimondo van Riel (Herzog Ludowico), Fritz Greiner (Statthalter Ga- nossa), José Davert (Matteo), Olga Limburg (Teresa), Karl Etlinger (Prälat), Denise Legeay, Albert Paulig (alter Polizeipräfekt), Apoloni Campella (Zigano) / Produktion: Hape-Film Co. GmbH, Berlin; Gaumont, Paris/ Produzenten: Harry Piel, Heinrich Nebenzahl / Aufnahmeleitung: Edmund Heuberger / Drehzeit: April-Juni 1925 / Atelier: Trianon-Atelier, Berlin / Außenaufnahmen: Italien, u.a. bei Rom / Zensur: B.10835 v. 6.7.1925, 8 Akte, 3259 m, Jugendverbot / Uraufführung: 27.7.1925, Mozartsaal, Berlin Kopie: Bundesarchiv, Berlin, 35mm, 2814 m Vorfilme Marionetten Deutschland 1922 / Produktion: Werbefilm GmbH Julius Pinschewer, Berlin, im Auftrag von Christian Adalbert Kupferberg & Co., Mainz / Werbung für Kupferberg „Gold-Sekt“ / Kamera: Heinrich Ba- lasch / Zensur: B.5187 v. 21.1.1922, 65 m, Jugendfrei Kopie: Bundesarchiv, Berlin, 35mm, viragiert, 60 m Der Gardasee Deutschland 1926 / Produktion: Filmfabrik Linke, Dresden / Zensur: B.14029 v. 1.11.1926, 1 Akt, 206 m, Jugendfrei Kopie: Bundesarchiv, Berlin, 35mm, 180 m Zigano, der Brigant von Monte Diavolo In den Zwanziger Jahren ist Harry Piel bekannt wie ein bunter Hund. -

Collection Adultes Et Jeunesse

bibliothèque Marguerite Audoux collection DVD adultes et jeunesse [mise à jour avril 2015] FILMS Héritage / Hiam Abbass, réal. ABB L'iceberg / Bruno Romy, Fiona Gordon, Dominique Abel, réal., scénario ABE Garage / Lenny Abrahamson, réal ABR Jamais sans toi / Aluizio Abranches, réal. ABR Star Trek / J.J. Abrams, réal. ABR SUPER 8 / Jeffrey Jacob Abrams, réal. ABR Y a-t-il un pilote dans l'avion ? / Jim Abrahams, David Zucker, Jerry Zucker, réal., scénario ABR Omar / Hany Abu-Assad, réal. ABU Paradise now / Hany Abu-Assad, réal., scénario ABU Le dernier des fous / Laurent Achard, réal., scénario ACH Le hérisson / Mona Achache, réal., scénario ACH Everyone else / Maren Ade, réal., scénario ADE Bagdad café / Percy Adlon, réal., scénario ADL Bethléem / Yuval Adler, réal., scénario ADL New York Masala / Nikhil Advani, réal. ADV Argo / Ben Affleck, réal., act. AFF Gone baby gone / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF The town / Ben Affleck, réal. AFF L'âge heureux / Philippe Agostini, réal. AGO Le jardin des délices / Silvano Agosti, réal., scénario AGO La influencia / Pedro Aguilera, réal., scénario AGU Le Ciel de Suely / Karim Aïnouz, réal., scénario AIN Golden eighties / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Hotel Monterey / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Jeanne Dielman 23 quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE La captive / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE Les rendez-vous d'Anna / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario AKE News from home / Chantal Akerman, réal., scénario, voix AKE De l'autre côté / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Head-on / Fatih Akin, réal, scénario AKI Julie en juillet / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI L'engrenage / Fatih Akin, réal., scénario AKI Solino / Fatih Akin, réal. -

Film Film Film Film

City of Darkness, City of Light is the first ever book-length study of the cinematic represen- tation of Paris in the films of the émigré film- PHILLIPS CITY OF LIGHT ALASTAIR CITY OF DARKNESS, makers, who found the capital a first refuge from FILM FILMFILM Hitler. In coming to Paris – a privileged site in terms of production, exhibition and the cine- CULTURE CULTURE matic imaginary of French film culture – these IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION experienced film professionals also encounter- ed a darker side: hostility towards Germans, anti-Semitism and boycotts from French indus- try personnel, afraid of losing their jobs to for- eigners. The book juxtaposes the cinematic por- trayal of Paris in the films of Robert Siodmak, Billy Wilder, Fritz Lang, Anatole Litvak and others with wider social and cultural debates about the city in cinema. Alastair Phillips lectures in Film Stud- ies in the Department of Film, Theatre & Television at the University of Reading, UK. CITY OF Darkness CITY OF ISBN 90-5356-634-1 Light ÉMIGRÉ FILMMAKERS IN PARIS 1929-1939 9 789053 566343 ALASTAIR PHILLIPS Amsterdam University Press Amsterdam University Press WWW.AUP.NL City of Darkness, City of Light City of Darkness, City of Light Émigré Filmmakers in Paris 1929-1939 Alastair Phillips Amsterdam University Press For my mother and father, and in memory of my auntie and uncle Cover design: Kok Korpershoek, Amsterdam Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam isbn 90 5356 633 3 (hardback) isbn 90 5356 634 1 (paperback) nur 674 © Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 2004 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, me- chanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permis- sion of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessingiiUM-I the World's Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8812304 Comrades, friends and companions: Utopian projections and social action in German literature for young people, 1926-1934 Springman, Luke, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Springman, Luke. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 COMRADES, FRIENDS AND COMPANIONS: UTOPIAN PROJECTIONS AND SOCIAL ACTION IN GERMAN LITERATURE FOR YOUNG PEOPLE 1926-1934 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Luke Springman, B.A., M.A. -

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930)

The Film Music of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930) FIONA FORD, MA Thesis submitted to The University of Nottingham for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy DECEMBER 2011 Abstract This thesis discusses the film scores of Edmund Meisel (1894–1930), composed in Berlin and London during the period 1926–1930. In the main, these scores were written for feature-length films, some for live performance with silent films and some recorded for post-synchronized sound films. The genesis and contemporaneous reception of each score is discussed within a broadly chronological framework. Meisel‘s scores are evaluated largely outside their normal left-wing proletarian and avant-garde backgrounds, drawing comparisons instead with narrative scoring techniques found in mainstream commercial practices in Hollywood during the early sound era. The narrative scoring techniques in Meisel‘s scores are demonstrated through analyses of his extant scores and soundtracks, in conjunction with a review of surviving documentation and modern reconstructions where available. ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) for funding my research, including a trip to the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt. The Department of Music at The University of Nottingham also generously agreed to fund a further trip to the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and purchased several books for the Denis Arnold Music Library on my behalf. The goodwill of librarians and archivists has been crucial to this project and I would like to thank the staff at the following institutions: The University of Nottingham (Hallward and Denis Arnold libraries); the Deutsches Filminstitut, Frankfurt; the Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin; the BFI Library and Special Collections; and the Music Librarian of the Het Brabants Orkest, Eindhoven.