Systems of Conversational Interaction: a Study of Three East African Tribes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Public Disclosure Authorized THE GOVERNMENT OF KENYA MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, WATER AND NATURAL RESOURCES KENYA WATER SECURITY AND CLIMATE RESILIENCE PROGRAM (KWSCRP) Public Disclosure Authorized FINAL VULNERABLE AND MARGINALISED GROUPS FRAMEWORK (VMGF) Public Disclosure Authorized (P117635) April 7th 2015 Prepared by: Tito Kodiaga and Lazarus Kubasu Nolasco Senior Environmental Specialist and Senior Social Specialist Project Management Unit Kenya Water Security and Climate Resilience Project (KWSCRP) Public Disclosure Authorized Nairobi, Kenya. Page | 1 KWSCRP Vulnerable and Marginalized Groups Framework - VMGF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS APL Adaptable Program Loan ASAL Arid and Semi-Arid Lands AWSB Athi Water Services Board CDA Coast Development Authority CDD Community Driven Development CoK Constitution of Kenya CPS Country Partnership Strategy CAADP Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program CSO Civil society organizations CWSB Coast Water Services Board DSS Decision Support System EAs Environmental Assessments EA Executing Agency EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMCA Environmental Management and Coordination Act EMP Environmental Management Plan ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environmental and Social Management Framework ESMP Environmental and Social Management Plan FPIC Free, prior and informed consultation FS Feasibility Study GDP Gross Domestic Product GIS Geographic Information System GIZ German Agency for International GOK Government of Kenya GRM Grievance Redress Mechanism GRC Grievance Redress -

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for All Africa People Groups & All LR-Upgs = Least-Reached

2020 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups (LR-UPGs) Source: Joshua Project data, www.joshuaproject.net To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] 2020 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & all LR-UPGs = Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. All 48 Africa countries & 8 islands & People Groups & LR-UPG are included. LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier definition = FR = 0.1% Christian or less AFRICA SUMMARY: 3,702 total Africa People Groups; 957 total Africa Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. Downloaded in October 2019 from www.joshuaproject.net * * * Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country shaded = LR-UPG; white-not shaded = not LR-UPG * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:9,15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commanded us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. -

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples' Issues

Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples’ Issues Republic of Kenya Country Technical Notes on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues The Republic of Kenya Submitted by: IWGIA April 2012 Disclaimer The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations ‗developed‘ and ‗developing‘ countries are intended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgment about the stage reached by a particular country or area in the development process. All rights reserved Table of Contents Country Technical Note on Indigenous Peoples‘ Issues- The Republic of Kenya ......... 1 Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 1. The indigenous peoples of Kenya ......................................................................... 2 1.1 The national context ................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Terminology ............................................................................................................ 4 1.3 The indigenous peoples of Kenya .............................................................................. -

The Discursive Construction of Kenyan Ethnicities in Online Political Talk

THE DISCURSIVE CONSTRUCTION OF KENYAN ETHNICITIES IN ONLINE POLITICAL TALK EVANS ANYONA ONDIGI A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS, UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE. SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ZANNIE BOCK MARCH 2019 i http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ KEY WORDS Discourse Kenya Ethnicity Politics Ethnic polarisation Media Facebook Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) Engagement Face-work ii http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ ABSTRACT Multi-paradigmatically qualitative, and largely in the fashion of the critical theory, this study seeks to explore how a selection of Kenyans construct, manipulate and negotiate ethnic categories in a discussion of national politics on two Facebook sites over a period of fourteen and a half months, at the time of the 2013 national elections. Kenya has at least 42 ethnic communities, and has been described as a hotbed of ethnic polarisation. The study is interested in how the participants use language to position themselves and others in relation to ethnicity, as well as to draw on or make reference to notions of Kenyan nationalism. The data for this study is drawn from Facebook discussions on two different groups: one ‘open’ and one ‘closed’. The data also includes participants from different ethnic groups and political leanings. Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA), Engagement and Face-work are used as theoretical frameworks to explore how participants draw on different discourses to construct their ethnicities and position themselves as Kenyan nationals. The analysis also explores how informants expand and contract the dialogic space, as well as how they perform face-work during these interactions. -

Downloaded From

Spaces of insecurity : human agency in violent conflicts in Kenya Witsenburg, K.; Zaal, A.F.M. Citation Witsenburg, K., & Zaal, A. F. M. (2012). Spaces of insecurity : human agency in violent conflicts in Kenya. African Studies Centre, Leiden. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/20295 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) License: Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/20295 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Spaces of insecurity African Studies Centre African Studies Collection, vol. 45 Spaces of insecurity Human agency in violent conflicts in Kenya Karen Witsenburg & Fred Zaal (editors) Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden The Netherlands [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl Cover design: Heike Slingerland Cover photo: Marsabit, Ola Daba. Refugees in 2007, from the ethnic clashes between Gabra and Borana after the Turbi Massacre, 2005 (Photo: Karen Witsenburg) Printed by Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede ISSN: 1876-018X ISBN: 978-90-5448-120-1 © Karen Witsenburg & Fred Zaal, 2012 Prologue As I was not involved in the production of this book, I felt honoured when Karen Witsenburg asked me to write a prologue for it. She said she would like me to write one, even if I were too busy to read all of it beforehand. But I felt uncom- fortable with the idea of writing some ritual laudatory remarks about something I had not really read, and so I asked her to send me the whole manuscript. I was immediately captured and read all of it. Often, collected volumes are criticised as being weakly integrated ‘bookbinders’ syntheses’, but this one is a very good book. -

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for All Africa People

2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & Least-Reached-Unreached People Groups (LR-UPGs) Source: Joshua Project; www.joshuaproject.net To order prayer resources or for inquiries, contact email: [email protected] 2021 Daily Prayer Guide for all Africa People Groups & all LR-UPGs = Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. 49 Africa countries & 9 islands & People Groups & LR-UPG are included. AFRICA SUMMARY: 3,713 total People Groups; 996 total Least-Reached--Unreached People Groups. Downloaded in August 2020 from www.joshuaproject.net LR-UPG defin: less than 2% Evangelical & less than 5% total Christian Frontier (FR) definition: 0% to 0.1% Christian Why pray--God loves lost: world UPGs = 7,407; Frontier = 5,042. * * * Color code: green = begin new area; blue = begin new country * * * "Prayer is not the only thing we can can do, but it is the most important thing we can do!" * * * Let's dream God's dreams, and fulfill God's visions -- God dreams of all people groups knowing & loving Him! * * * Revelation 7:9, "After this I looked and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and in front of the Lamb." Why Should We Pray For Unreached People Groups? * Missions & salvation of all people is God's plan, God's will, God's heart, God's dream, Gen. 3:15! * In the Great Commissions Jesus commands us to reach all peoples in the world, Matt. 28:19-20! * People without Jesus are eternally lost, & Jesus is the only One who can save them, John 14:6! * We have been given "the ministry & message of reconciliation", in Christ, 2 Cor. -

Across-The-Board Tonal Polarity in Kipsigis: Implications for the Morphology-Phonology Interface

Across-the-board tonal polarity in Kipsigis: Implications for the morphology-phonology interface Maria Kouneli (University of Leipzig) Yining Nie (New York University) [email protected] [email protected] October 2020, to appear in Language Abstract Using novel data from Kipsigis (Southern Nilotic; Kenya), we present the first attested case of across-the-board paradigmatic tonal polarity. The nominative case forms of nominal modifiers (adjectives, possessives, and demonstratives) are segmentally identical to their oblique case counterparts but have the opposite tonal pattern across-the-board: nominative and oblique modifiers differ in not just one but EVERY tonal specification. Kipsigis polarity thus results in maximal tonal contrast between two morphologically related words. We show how the Kipsigis pattern may be captured in an item-and-process theory of morphology with dedicated exchange mechanisms and an item-and-arrangement theory that allows for morpheme-specific phonology; we suggest that an item-and-process approach may provide a more straightforward account.* Keywords: Morphology, phonology, tone, polarity, Kipsigis, Nilotic * Authors are listed alphabetically. We are grateful to our Kipsigis language consultants Sharon Chelangat, Mercy Chep, Nehemiah Cheruiyot, Boniface Kemboi, Donald Kibet, Enock Kipkorir, Emmanuel Kiprono, Wesley Kirui, Hillary Mosonik, Victor Mutai, Amos Ngeno, and Philemon Ronoh. Thank you to Maria Gouskova, Florian Lionnet, Jochen Trommer, and audiences at NYU and NELS 49 for their feedback at various stages of this work. We also thank Language editor Andries Coetzee and two anonymous reviewers for their very helpful comments. This research was supported in part by SSHRC Doctoral Fellowship #752-2016-0096 to the second author. -

Transformation of Female Circumcision Among the Kipsigis of Bomet County: Kenya; 1945-2014

TRANSFORMATION OF FEMALE CIRCUMCISION AMONG THE KIPSIGIS OF BOMET COUNTY: KENYA; 1945-2014 BY WERUNGA DAMARIS SIMULI C50/27101/2014 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS (HISTORY) OF KENYATTA UNIVERSITY. NOVEMBER, 2017 ii iii DEDICATION This thesis is a dedication to my parents who taught me that the best kind of knowledge is that, which is acquired for its own sake. It is also dedicated to my siblings who always reminded me that even the largest task can be accomplished when I take one step at a time. You have been a great source of motivation and inspiration. Your kindness and selflessness shan’t be forgotten. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This work would not have been possible without the support of several people. I wish to express my gratitude to all of them who were abundantly helpful and offered invaluable assistance, support, and guidance. I am grateful to the entire Kenyatta University fraternity for providing me an ample time and environment full of resourceful human kinds to assist during my entire studies. I would like to sincerely acknowledge my supervisors, Dr. Susan Mwangi Owino and Dr. David Okelo for their guidance and support throughout this study. I appreciate you two for being the ideal thesis supervisors. My vote of thanks also goes to Dr. Peter Wekesa Wafula for his sage advice, patient encouragement, guidance and insightful criticisms which aided my thesis in innumerable ways. I would also like to thank the entire Bomet County Commissioner’s office team who helped me trace respondents and the entire community for allocating their valuable time to be interviewed. -

Morphological Evidence for the Coherence of East Sudanic

article⁄Morphological Evidence for the Coherence of East Sudanic author⁄Roger M. Blench abstract⁄East Sudanic is the largest and most complex branch of Nilo-Saharan. First mooted by Greenberg in 1950, who included seven branches, it was expanded in his 1963 publication to include Ama (Nyimang) and Temein and also Kuliak, not now considered part of East Sudanic. However, demonstrating the coherence of East Sudanic and justifying an internal structure for it have remained problematic. The only signicant monograph on this topic is Bender’s The East Sudanic Languages, which uses largely lexical evidence. Bender proposed a subdivision into Ek and En languages, based on pronouns. Most subsequent scholars have accepted his Ek cluster, consisting of Nubian, Nara, Ama, and Taman, but the En cluster (Surmic, E. Jebel, Temein, Daju, Nilotic) is harder to substantiate. Rilly has put forward strong arguments for the inclusion of the extinct Meroitic language as coordinate with Nubian. In the light of these diculties, the paper explores the potential for morphology to provide evidence for the coherence of East Sudanic. The paper reviews its characteristic tripartite number-marking system, consisting of singulative, plurative, and an unmarked middle term. These are associated with specic segments, the singulative in t- and plurative in k- as well as a small set of other segments, characterized by complex allomorphy. These are well preserved in some branches, fragmentary in others, and seem to have vanished completely in the Ama group, leaving only traces now fossilized in Dinik stems. The paper concludes that East Sudanic does have a common morphological system, despite its internal lexical diversity. -

4Th Febraury, 2015 NAME REG No READER SUPERVISOR TOPIC

KENYATTA UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND LINGUISTICS Website: www.ku.ac.ke Tel: 8710901-19 Ext. 57338, 4112 4th Febraury, 2015 NAME REG No READER SUPERVISOR TOPIC 1 Juliet Akinyi C50/CE/14024/2009 Dr. Nyamasyo Dr. Phyllis Mwangi The assessment of language games used in Dr. Kebeya Dr. Purity Nthiga teaching language skills in upper primary classes in Kilifi County. 2 Esther Mwaniki 0720 412 795 Dr. Gachara Dr. Emily Ogutu Face threatening acts in open day discourse. N. Dr. Daniel Orwenjo Dr. Kenneth Ngure 3 Martin Maina 0708659629 1. The nominal group in Gikuyu Language a C50/CE/25334/2013 functional grammar approach. 2. The syntax of the cleft construction in Gikuyu language: A minimalist perspective. 4 Williams S. 0720287378 Motivation and language learning strategies used Kawira C50/CE/24774/2012 by secondary school teachers in Tigania West Sub- county. 5 Susan 0720899262 Vocabulary learning strategies of Kenyan hsk W.Wachira C182/26343/2013 candidates. P.hd 6 Loise Wothaya 0721278974 Word formation processes used by matatu Sacco’s Mwangi C50/CE/21238/2013 in Nyeri county. 7 Alfred Oluoch 0713559188 Language in contact: maintenance and shift among Amollo C50/CE/25344/2012 the Nubians of KIbigori in Kisumu county-Kenya. 8 John Kavungula 0721 360 313 1. A study of conversational implicature in Mutisya C50/CE/24434/2013 the play betrayal in the city by Francis Imbuga. 2. Use of personal pronouns in political speeches. A comparative study of the pronominal choices of two Kenyan Presidents. 9 Elijah Chege 0714 856140 A study on the linguistic bearing of communication Ndumia C50/CE/22829/2011 apprehension- a case of form three students in Mukuuni high School. -

Change and Continuity in Riddles and Riddle Performance Among the Kipsigis of Kericho County, Kenya

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN RIDDLES AND RIDDLE PERFORMANCE AMONG THE KIPSIGIS OF KERICHO COUNTY, KENYA ESTHER CHERONO A Thesis Submitted to Graduate School in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Literature of Egerton University EGERTON UNIVERSITY JULY, 2020 ii COPYRIGHT ©2020, Esther Cherono All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means: whether mechanical, electronic, photocopying, scanning, recording or otherwise without prior written permission of the author or Egerton University on behalf of the author. iii DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my beloved mother, Pauline C. Misik, my supportive uncle, Amos A. Misik, and my late father, Joel A. Misik who was and still is a source of inspiration in my life. Special dedication goes to my beloved husband, Joseph Namunyu and my children; Jael, Josphine, Jeiel and Jeriel for their continued motivation. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to Almighty God whose grace has seen me through this work. Special gratitude goes to my supervisors: Prof. Fugich Wako and Dr. Dishon Kweya who guided me through the thesis to completion. I am also indebted to Prof. Ilieva, Dr. Bartoo, Dr, Walunywa, and all the lecturers in the department for their support and encouragement. Further, my gratitude goes to Prof. Moses Rotich and his family for providing me with accommodation while I was working from the university. I also sincerely appreciate the informants including the resource persons, teachers, pupils, and the research guides Mathew Rutto and Beatrice Chepng’eno who greatly assisted me during my field work, without whom this work would not have been completed. -

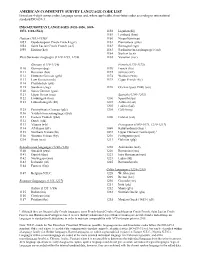

American Community Survey Language Code List

AMERICAN COMMUNITY SURVEY LANGUAGE CODE LIST Listed are 4-digit census codes, language names and, where applicable, three-letter codes according to international standard ISO 639-3. INDO-EUROPEAN LANGUAGES (1053-1056, 1069- 1073, 1110-1564) 1158 Ligurian (lij) 1159 Lombard (lmo) Haitian (1053-1056)1 1160 Neapolitan (nap) 1053 Guadeloupean Creole French (gcf) 1161 Piemontese (pms) 1054 Saint Lucian Creole French (acf) 1162 Romagnol (rgn) 1055 Haitian (hat) 1163 Sardinian (macrolanguage) (srd) 1164 Sicilian (scn) West Germanic languages (1110-1139, 1234) 1165 Venetian (vec) German (1110-1124) French (1170-1175) 1110 German (deu) 1170 French (fra) 1111 Bavarian (bar) 1172 Jèrriais (nrf) 1112 Hutterite German (geh) 1174 Walloon (wln) 1113 Low German (nds) 1175 Cajun French (frc) 1114 Plautdietsch (ptd) 1115 Swabian (swg) 1176 Occitan (post 1500) (oci) 1120 Swiss German (gsw) 1121 Upper Saxon (sxu) Spanish (1200-1205) 1122 Limburgish (lim) 1200 Spanish (spa) 1123 Luxembourgish (ltz) 1201 Asturian (ast) 1202 Ladino (lad) 1125 Pennsylvania German (pdc) 1205 Caló (rmq) 1130 Yiddish (macrolanguage) (yid) 1131 Eastern Yiddish (ydd) 1206 Catalan (cat) 1132 Dutch (nld) 1133 Vlaams (vls) Portuguese (1069-1073, 1210-1217) 1134 Afrikaans (afr) 1069 Kabuverdianu (kea) 1 1135 Northern Frisian (frr) 1072 Upper Guinea Crioulo (pov) 1 1136 Western Frisian (fry) 1210 Portuguese (por) 1234 Scots (sco) 1211 Galician (glg) Scandinavian languages (1140-1146) 1218 Aromanian (aen) 1140 Swedish (swe) 1220 Romanian (ron) 1141 Danish (dan) 1221 Istro Romanian (ruo)