'The New (Old) Play': Q1 Hamlet and the Texts Around

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

{PDF} the First Quarto of Hamlet 1St Edition Ebook

THE FIRST QUARTO OF HAMLET 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Shakespeare | 9780521653909 | | | | | The First Quarto of Hamlet 1st edition PDF Book The Murder of Gonzago is played before the assembled court, but is interrrupted when Claudius suddenly rises and leaves. This is the only modernised critical edition of the quarto in print. Scarce thus. The First Quarto of Hamlet. A handful of sources contributed significantly to the creation of Hamlet. King Richard II. Condition: Very Good. The first critic of the , first Spanish translation of Shakespeare's Hamlet. British Library copies of Hamlet contains detailed bibliographic descriptions of all the quarto copies of the play. Great Neck, N. Perhaps most crucially, Amleth lacks Hamlet's melancholy disposition and long self-reflexive soliloquies, and he survives after becoming king" British Library. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that Shakespeare did at least consult Saxo. There is an entire scene between Horatio and Gertrude in which Horatio tells her that Hamlet has escaped from the ship after discovering Claudius' plan to kill him. Protected under mylar cover. Published by Printed for P[hilip] C[hetwinde], London Theatrical adaption. Some scenes take place at a different point in the story — for example Hamlet's " To be, or not to be " soliloquy occurs in Act Two, immediately after Polonius proposes to set up an "accidental" meeting between Hamlet and Ophelia. According to the title page, the play was printed 'as it is now acted at His Highness the Duke of York's Theatre. Namespaces Article Talk. Occasional neat underlinings and scholarly notes, some minor marginal wormholes. -

June 17 – Jan 18 How to Book the Plays

June 17 – Jan 18 How to book The plays Online Select your own seat online nationaltheatre.org.uk By phone 020 7452 3000 Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 8pm In person South Bank, London, SE1 9PX Mon – Sat: 9.30am – 11pm Other ways Friday Rush to get tickets £20 tickets are released online every Friday at 1pm Saint George and Network Pinocchio for the following week’s performances. the Dragon 4 Nov – 24 Mar 1 Dec – 7 Apr Day Tickets 4 Oct – 2 Dec £18 / £15 tickets available in person on the day of the performance. No booking fee online or in person. A £2.50 fee per transaction for phone bookings. If you choose to have your tickets sent by post, a £1 fee applies per transaction. Postage costs may vary for group and overseas bookings. Access symbols used in this brochure CAP Captioned AD Audio-Described TT Touch Tour Relaxed Performance Beginning Follies Jane Eyre 5 Oct – 14 Nov 22 Aug – 3 Jan 26 Sep – 21 Oct TRAVELEX £15 TICKETS The National Theatre Partner for Innovation Partner for Learning Sponsored by in partnership with Partner for Connectivity Outdoor Media Partner Official Airline Official Hotel Partner Oslo Common The Majority 5 – 23 Sep 30 May – 5 Aug 11 – 28 Aug Workshops Partner The National Theatre’s Supporter for new writing Pouring Partner International Hotel Partner Image Partner for Lighting and Energy Sponsor of NT Live in the UK TBC Angels in America Mosquitoes Amadeus Playing until 19 Aug 18 July – 28 Sep Playing from 11 Jan 2 3 OCTOBER Wed 4 7.30 Thu 5 7.30 Fri 6 7.30 A folk tale for an Sat 7 7.30 Saint George and Mon 9 7.30 uneasy nation. -

Versailles: French TV Goes Global Brexit: Who Benefits? with K5 You Can

July/August 2016 Versailles: French TV goes global Brexit: Who benefits? With K5 you can The trusted cloud service helping you serve the digital age. 3384-RTS_Television_Advert_v01.indd 3 29/06/2016 13:52:47 Journal of The Royal Television Society July/August 2016 l Volume 53/7 From the CEO It’s not often that I Huw and Graeme for all their dedica- this month. Don’t miss Tara Conlan’s can say this but, com- tion and hard work. piece on the gender pay gap in TV or pared with what’s Our energetic digital editor, Tim Raymond Snoddy’s look at how Brexit happening in politics, Dickens, is off to work in a new sector. is likely to affect the broadcasting and the television sector Good luck and thank you for a mas- production sectors. Somehow, I’ve got looks relatively calm. sive contribution to the RTS. And a feeling that this won’t be the last At the RTS, however, congratulations to Tim’s successor, word on Brexit. there have been a few changes. Pippa Shawley, who started with us Advance bookings for September’s I am very pleased to welcome Lynn two years ago as one of our talented RTS London Conference are ahead of Barlow to the Board of Trustees as the digital interns. our expectations. To secure your place new English regions representative. It may be high summer, but RTS please go to our website. She is taking over from the wonderful Futures held a truly brilliant event in Finally, I’d like to take this opportu- Graeme Thompson. -

Demarcating Dramaturgy

Demarcating Dramaturgy Mapping Theory onto Practice Jacqueline Louise Bolton Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Workshop Theatre, School of English August 2011 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. 11 Acknowledgements This PhD research into Dramaturgy and Literary Management has been conducted under the aegis of an Arts and Humanities Research Council Collaborative Doctoral Award; a collaboration between the University of Leeds and West Yorkshire Playhouse which commenced in September 2005. I am extremely grateful to Alex Chisholm, Associate Director (Literary) at West Yorkshire Playhouse, and Professor Stephen Bottoms and Dr. Kara McKechnie at the University of Leeds for their intellectual and emotional support. Special thanks to Professor Bottoms for his continued commitment over the last eighteen months, for the time and care he has dedicated to reading and responding to my work. I would like to take this opportunity to thank everybody who agreed to be interviewed as part of this research. Thanks in particular to Dr. Peter Boenisch, Gudula Kienemund, Birgit Rasch and Anke Roeder for their insights into German theatre and for making me so welcome in Germany. Special thanks also to Dr. Gilli Bush-Bailey (a.k.a the delightful Miss. Fanny Kelly), Jack Bradley, Sarah Dickenson and Professor Dan Rebellato, for their faith and continued encouragement. -

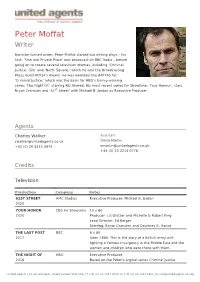

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

March 2016 Conversation

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE WNDC IN WASHINGTON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION DIANA OWEN ♦ Tuesday, February 23 As we commemorate SHAKESPEARE 400, a global celebration of the poet’s life and legacy, the GUILD is delighted to co-host a WOMAN’S NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CLUB gathering with DIANA OWEN, who heads the SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST in Stratford-upon-Avon. The TRUST presides over such treasures as Mary Arden’s House, WITTEMORE HOUSE Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and the home in which the play- 1526 New Hampshire Avenue wright was born. It also preserves the site of New Place, the Washington mansion Shakespeare purchased in 1597, and in all prob- LUNCH 12:30. PROGRAM 1:00 ability the setting in which he died in 1616. A later owner Luncheon & Program, $30 demolished it, but the TRUST is now unearthing the struc- Program Only , $10 ture’s foundations and adding a new museum to the beautiful garden that has long delighted visitors. As she describes this exciting project, Ms. Owen will also talk about dozens of anniversary festivities, among them an April 23 BBC gala that will feature such stars as Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen. PEGGY O’BRIEN ♦ Wednesday, February 24 Shifting to the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY, an American institution that is marking SHAKESPEARE 400 with a national tour of First Folios, we’re pleased to welcome PEGGY O’BRIEN, who established the Library’s globally acclaimed outreach initiatives to teachers and NATIONAL ARTS CLUB students in the 1980s and published a widely circulated 15 Gramercy Park South Shakespeare Set Free series with Simon and Schuster. -

2017-Richard-3-Learning-Resources

LEARNING RESOURCES SYNOPSIS 2 QUICK FACTS 3 PERFORMANCE HISTORY 4 SOURCES AND SHAKESPEARE SHAPING HISTORY 5 HISTORY OF WOMEN PLAYING MALE ROLES IN SHAKESPEARE 6 CHARACTERS 8 THEMES 12 FROM THE DIRECTOR 17 DESIGN 18 OTHER RESOURCES 21 ACTIVITIES 23 EXERCISE ONE 23 EXERCISE TWO 24 EXERCISE THREE 25 EXERCISE FOUR 26 LEARNING RESOURCES RICHARD 3 © Bell Shakespeare 2017, unless otherwise indicated. Provided all acknowledgements are retained, this material may be used, Page 1 of 26 reproduced and communicated free of charge for non-commercial educational purposes within Australian and overseas schools RICHARD 3 SYNOPSIS England is enjoying a period of peace after a long civil war between the royal families of York and Lancaster, in which the Yorks were victorious and Henry VI was murdered (by Richard). King Edward IV is newly declared King, but his youngest brother, Richard (Gloucester) is resentful of Edward’s power and the general happiness of the state. Driven by ruthless ambition and embittered by his own deformity, he initiates a secret plot to take the throne by eradicating anyone who stands in his path. Richard has King Edward suspect their brother Clarence of treason and he is brought to the Tower by Brackenbury. Richard convinces Clarence that Edward’s wife, Queen Elizabeth, and her brother Rivers, are responsible for this slander and Hastings’ earlier imprisonment. Richard swears sympathy and allegiance to Clarence, but later has him murdered. Richard then interrupts the funeral procession of Henry VI to woo Lady Anne (previously betrothed to Henry VI’s deceased son, again killed by Richard). He falsely professes his love for her as the cause of his wrong doings, and despite her deep hatred for Richard, she is won and agrees to marry him. -

"'A Complicated and Unpleasant Investigation': the Arden Shakespeare 1899-1924" by Gabriel Egan This Paper Arises From

Egan, Gabriel. 2007d. "'''A complicated and unpleasant investigation': The Arden Shakespeare 1899-1924': A paper delivered on 12 July at the conference 'Open the Book, Open the Mind: The 2007 meeting of the Society for History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing (SHARP)' at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, 11-15 July." "'A complicated and unpleasant investigation': The Arden Shakespeare 1899-1924" by Gabriel Egan This paper arises from a survey of Shakespeare play editions in the twentieth century. I'm particularly interested in what those who made editions thought they were doing, how confident they felt about their work, how they thought readers would respond to the textual problems that arise in editing old plays, and how editors' assumptions about their readers were manifested in the editions that they produced. My published title in the programme covers the whole century of editions, but I'm going largely to confine my remarks to just one editorial project. For those of you who like to see the big picture first, however, I can offer a brief overview of just one of those variables I mentioned: editorial confidence [SLIDE]. I see it going like this, from a low at the start of the twentieth-century, through to a peak in the 1970s, and back to a low now. From the detailed history behind this pattern, I have room on this chart to pull just a few keys moments. [SLIDE] First, A. W. Pollard's book Shakespeare Folios and Quartos (1909) distinguished the good from the bad quartos and gave editors reasons to suppose that the good ones are textually close to Shakespeare's own papers. -

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Dialect and Voice

Dialect Coaching for Screen 2014/2015/2016 Nov 16 – Feb 2017 Roseline Productions Dialect Coach for Will Ferrell, John C Reilly: Holmes and Watson Nov 2016 Sky Dialect Coach Bliss Nov 2016 BBC Dialect Coach for Zombie Boy: Silent Witness Aug 2016 Sky Dialect Coach for Iwan Rheon and Dimitri Leonidas: Riviera Jan/Feb 2016 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: ADR: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Oct 2015 Jellylegs/Sky 1 Dialect Coach: Rovers directed by Craig Cash Oct 2015 Channel 4 Dialect Coach: Raised By Wolves directed by Ian Fitzgibbon Sept 2015 LittleRock Pictures/Sky Dialect /voice coach: Elizabeth, Michael and Marlon (Joseph Fiennes, Stockard Channing, Brian Cox) January – May 2015 BBC2/ITV, London Dialect Coach (East London): Cradle to Grave – directed by Sandy Johnson January – April 2015 Working Title/Sky Dialect Coach (Gen Am, Italian): You, Me and the Apocalypse – TV directed by Michael Engler/Saul Metzstein September 2014 Free Range Films Ltd, London Dialect/voice coach (Leeds): The Lady in the Van – Feature directed by Nicholas Hytner May 2014 Wilma TV, Inc. for Discovery Channel, New York Dialect Coach (Australian): Amerikan Kanibal - Docudrama February/March 2014 Mad As Birds Dialect Coach (Various Period US accents): Set Fire to the Stars - Feature directed by Andy Goddard February and June 2014 BBC 3 Dialect Coach (Liverpool and Australian): Crims - TV directed by James Farrell Dialect and Voice Coaching for theatre 2016 Oct 2016 Park Theatre, Dialect support (New York: Luv directed by Gary Condes Oct 2016 Kings Cross -

Cheltlf12 Brochure

SponSorS & SupporterS Title sponsor In association with Broadcast Partner Principal supporters Global Banking Partner Major supporters Radio Partner Festival Partners Official Wine Working in partnership Official Cider 2 The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival dIREctor Festival Assistant Jane Furze Hannah Evans Artistic dIREctor Festival INTERNS Sarah Smyth Lizzie Atkinson, Jen Liggins BOOK IT! dIREctor development dIREctor Jane Churchill Suzy Hillier Festival Managers development OFFIcER Charles Haynes, Nicola Tuxworth Claire Coleman Festival Co-ORdinator development OFFIcER Rose Stuart Alison West Welcome what words will you use to describe your festival experience? Whether it’s Jazz, Science, Music or Literature, a Cheltenham Festival experience can be intellectually challenging, educational, fun, surprising, frustrating, shocking, transformational, inspiring, comical, beautiful, odd, even life-changing. And this year’s The Times Cheltenham Literature Festival is no different. As you will see when you browse this brochure, the Festival promises Contents 10 days of discussion, debate and interview, plus lots of new ways to experience and engage with words and ideas. It’s a true celebration of 2012 NEWS 3 - 9 the power of the word - with old friends, new writers, commentators, What’s happening at this year’s Festival celebrities, sports people and scientists, and from children’s authors, illustrators, comedians and politicians to leading opinion-formers. FESTIVAL PROGRAMME 10 - 89 Your day by day guide to events I can’t praise the team enough for their exceptional dedication and flair in BOOK IT! 91 - 101 curating this year’s inspiring programme. However, there would be no Festival Our Festival for families and without the wonderful enthusiasm of our partners and loyal audiences and we young readers are extremely grateful for all the support we receive. -

Edward De Vere and the Two Shrew Plays

The Playwright’s Progress: Edward de Vere and the Two Shrew Plays Ramon Jiménez or more than 400 years the two Shrew plays—The Tayminge of a Shrowe (1594) and The Taming of the Shrew (1623)—have been entangled with each other in scholarly disagreements about who wrote them, which was F written first, and how they relate to each other. Even today, there is consensus on only one of these questions—that it was Shakespeare alone who wrote The Shrew that appeared in the Folio . It is, as J. Dover Wilson wrote, “one of the most diffi- cult cruxes in the Shakespearian canon” (vii). An objective review of the evidence, however, supplies a solution to the puz- zle. It confirms that the two plays were written in the order in which they appear in the record, The Shrew being a major revision of the earlier play, A Shrew . They were by the same author—Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, whose poetry and plays appeared under the pseudonym “William Shakespeare” during the last decade of his life. Events in Oxford’s sixteenth year and his travels in the 1570s support composition dates before 1580 for both plays. These conclusions also reveal a unique and hitherto unremarked example of the playwright’s progress and development from a teenager learning to write for the stage to a journeyman dramatist in his twenties. De Vere’s exposure to the in- tricacies and language of the law, and his extended tour of France and Italy, as well as his maturation as a poet, caused him to rewrite his earlier effort and pro- duce a comedy that continues to entertain centuries later. -

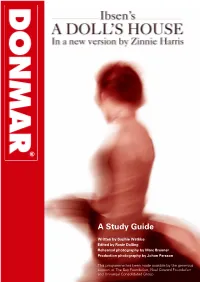

A Study Guide

A Study Guide Written by Sophie Watkiss Edited by Rosie Dalling Rehearsal photography by Marc Brenner Production photography by Johan Persson This programme has been made possible by the generous support of The Bay Foundation, Noel Coward Foundation and Universal Consolidated Group 1 Contents Section 1: Cast and Creative Team Section 2: A new version of a classic text The social and cultural positioning of Henrik Ibsen’s original play A DOLL’S HOUSE transposed in time Synopsis, Act 1 Section 3: Inside the rehearsal room The rehearsal process Rehearsing the final scene of Act One Stage 1: contextualising the scene and investigating the text Stage 2: playing the scene Conversations inside the rehearsal room, week 3. Toby Stephens – Thomas Maggie Wells – Annie Anton Lesser – Dr Rank Christopher Eccleston – Neil Kelman Tara Fitzgerald – Christine Lyle Section 4: Endnotes and bibliography 2 section 1 Cast and Creative Team Cast GILLIAN ANDERSON. NORA Trained: Goodman Theatre School. Theatre: includes The Sweetest Swing in Baseball (Royal Court), What the Night is For (Comedy), The Philanthropist (Connecticut), Absent Friends (New York). Film: includes X-Files: I Want to Believe, Boogie Woogie, How to Lose Friends & Alienate People, Straightheads, The Last King of Scotland, A Cock and Bull Story, The Mighty Celt, House of Mirth – BAFTA Award, Playing by Heart, The X-Files Movie, The Mighty. Television: includes Bleak House, X-Files – Emmy Award. CHRISTOPHER ECCLESTON. NEIL KELMAN Trained: Central School of Speech and Drama. Theatre: includes Electricity, Hamlet (WYP), Miss Julie (Haymarket), Waiting at the Water’s Edge (Bush), Encounters (NT Studio), Aide-Memoire (Royal Court), Abingdon Square (NT/Shared Experience), Bent (NT), Dona Rosita the Spinster, A Streetcar Named Desire (Bristol Old Vic), The Wonder (Gate).