A Study Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Children and It

Pathé FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Press pack Released Friday 15 October 2004 - Scotland Only Released Friday 22 October 2004 - Nationwide For further information please contact: Emily Carr [email protected] Victoria Keeble [email protected] Bella Gubay [email protected] 020 7426 5700 Pathé FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Press pack Capitol Films and the UK Film Council present in association with the Isle of Man Film Commission and in association with Endgame Entertainment a Jim Henson Company Production a Capitol Films / Davis Films Production Written by: David Solomons Produced by: Nick Hirschkorn Lisa Henson Samuel Hadida Directed by: John Stephenson FIVE CHILDREN AND IT Cast List It .............................................................................. Eddie Izzard Cyril......................................................................... Jonathan Bailey Anthea...................................................................... Jessica Claridge Robert ...................................................................... Freddie Highmore Jane.......................................................................... Poppy Rogers The Lamb................................................................. Alec & Zak Muggleton Horace...................................................................... Alexander Pownall Uncle Albert............................................................. Kenneth Branagh Martha...................................................................... Zoë Wanamaker Father...................................................................... -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE Saffron Burrows, Oliver Chris and Belinda Stewart-Wilson join cast of Everything I Ever Wanted to Tell My Daughter About Men 29 January 2020 Shakespeare’s Globe is delighted to announce further casting for Everything I Ever Wanted to Tell My Daughter About Men, a new black comedy by actor and writer Lorien Haynes, directed by Tara Fitzgerald (Brassed Off, Game of Thrones), being hosted in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse on Thursday 20 February. Everything I Ever Wanted to Tell My Daughter About Men traces a woman’s relationship history backwards, exploring the impact of sexual assault, addiction and teen pregnancy on her adult relationships. Presented in association with RISE and The Circle, all profits from this event will go towards supporting survivors of sexual violence. Thanks in huge part to RISE’s work, the event will also mark the planned introduction of the Worldwide Sexual Violence Survivor Rights United Nations Resolution later this year, which addresses the global issue of sexual violence and pens into existence the civil rights of millions of survivors. Nobel-Prize nominee and founder of Rise, Amanda Nguyen, will introduce the evening. A silent auction will also take place on the night to highlight and raise awareness for the support networks available to those in need. Audience members will be able to bid on props from the production as well as a selection of especially commissioned rotary phones, exclusively designed by acclaimed British artists including Harland Miller, Natasha Law, Bella Freud and Emma Sargeant. The money raised by each phone will go to a rape crisis helpline chosen by the artist. -

Rights List : March 2020

Rights List : March 2020 Brotherstone Creative Management Mortimer House, Mortimer Street London W1T 3JH +44 (0) 7908 542 866 bcm-agency.com [email protected] Fiction Kirstin Innes SCABBY QUEEN Scenes From A Life Three days before her fifty-first birthday, Clio Campbell - one-hit-wonder, political activist, life-long-love and one- night-stand - kills herself in her friend Ruth's spare bedroom. And, as practical as she is, Ruth doesn't know what to do. Or how to feel. Because knowing and loving Clio Campbell was never straightforward. To Neil, she was his great unrequited love. He'd known it since their days on picket lines as teenagers. Now she's a sentence in his email inbox: Remember me well. The media had loved her as a sexy young starlet, but laughed her off as a ranting spinster as she aged. But with news of her suicide, Clio Campbell is transformed into a posthumous heroine for politically chaotic times. Stretching over five decades, taking in the miners' strikes to Brexit and beyond; hopping between a tiny Scottish island, a Brixton anarchist squat, the bloody Genoa G8 protests, the poll tax riots and Top of the Pops, Scabby Queen is a portrait of a woman who refuses to compromise, told by her friends and lovers, enemies and fans. As word spreads of what Clio has done, half a century of memories, of pain and of joy are wrenched to the surface. Those who loved her, those who hated her, and those that felt both ways at once, are forced to ask one question: Who was Clio Campbell? Reminiscent of Our Friends In The North, Jackie Kay’s Trumpet and Rachel Cusk’s The Flamethrowers, this is a multifaceted look at a complex female character, an examination of the way we obsess over and vilify female celebrities, and a political novel for our times. -

BFI Press Release: Missing Believed Wiped Bumper Christmas Stocking

For Immediate Release: Tuesday 7 November 2017, London. The BFI’s Missing Believed Wiped returns to BFI Southbank this December to present British television rediscoveries, not seen by audiences for decades, since their original transmission dates. The exciting, bespoke line-up of TV gems feature some of our most-loved television celebrities and iconic characters including Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part: Sex Before Marriage, Cilla Black in her eponymous BBC show featuring Dudley Moore , Jimmy Edwards in Whack-O!, a rare interview with Peter Davison about playing Doctor Who and a significant screen debut from a young Pete Postlethwaite. Lost for 50 years and thought only to survive in part, Till Death Us Do: Sex Before Marriage, originally broadcast on 2 January, 1967 on BBC1, sees Warren Mitchell’s Alf Garnett rail against the permissive society, featuring guest star John Junkin alongside regular cast members Dandy Nichols, Anthony Booth and Una Stubbs. Although the existence of this missing episode from the 2nd series has been known for some years, previous attempts to screen the episode had been refused with the print in the hands of a private collector. Having recently changed hands, MBW is delighted that access has been granted for this special one off screening, for one of 1960s best known and controversial UK television characters. Following last year’s successful screening of a previously lost episode of Jimmy Edwards’s popular 1950s BBC school-themed comedy romp Whack-O!, this year’s MBW programme includes a 1959 episode entitled The Empty Cash Box. Written by Frank Muir and Dennis Norden and starring Jimmy Edwards as the cane-happy headmaster, this episode was originally broadcast on the BBC on 1st December 1959. -

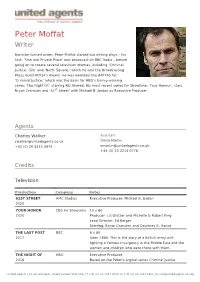

Peter Moffat Writer

Peter Moffat Writer Barrister turned writer, Peter Moffat started out writing plays – his first, ‘Fine and Private Place’ was broadcast on BBC Radio – before going on to create several television dramas, including ‘Criminal Justice, ‘Silk’ and ‘North Square,’ which he won the Broadcasting Press Guild Writer’s Award. He was awarded two BAFTAS for ‘Criminal Justice,’ which was the basis for HBO’s Emmy-winning series ‘The Night Of,’ starring Riz Ahmed. His most recent series for Showtime, ‘Your Honour,’ stars Bryan Cranston and ‘61st Street’ with Michael B. Jordan as Executive Producer. Agents Charles Walker Assistant [email protected] Olivia Martin +44 (0) 20 3214 0874 [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0778 Credits Television Production Company Notes 61ST STREET AMC Studios Executive Producer: Michael B. Jordan 2020 YOUR HONOR CBS for Showtime 10 x 60 2020 Producer: Liz Glotzer and Michelle & Robert King Lead Director: Ed Berger Starring: Bryan Cranston and Courtney B. Vance THE LAST POST BBC 6 x 60 2017 Aden 1965. This is the story of a British army unit fighting a Yemeni insurgency in the Middle East and the women and children who were there with them. THE NIGHT OF HBO Executive Producer 2016 Based on the Peter's orginal series Criminal Justice United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes UNDERCOVER BBC1 6 x60' with Sophie Okonedo and Adrian Lester, Denis 2015 Haysbert Director James Hawes, Exec Producer Peter Moffat THE VILLAGE series Company Pictures 6 x 60' with John Simm, Maxine Peake, Juliet Stevenson 1 / BBC1 Producer: Emma Burge; Director: Antonia Bird 2013 SILK 2 BBC1 6 x 60' With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Frances 2012 Barber, and Neil Stuke Producer: Richard Stokes; Directors: Alice Troughton, Jeremy Webb, Peter Hoar SILK BBC1 6 x 60' 2011 With Maxine Peake, Rupert Penry Jones, Natalie Dormer, Tom Hughes and Neil Stuke. -

Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank Production of Twelfth Night

2016 shakespeare’s globe Annual review contents Welcome 5 Theatre: The Globe 8 Theatre: The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse 14 Celebrating Shakespeare’s 400th Anniversary 20 Globe Education – Inspiring Young People 30 Globe Education – Learning for All 33 Exhibition & Tour 36 Catering, Retail and Hospitality 37 Widening Engagement 38 How We Made It & How We Spent It 41 Looking Forward 42 Last Words 45 Thank You! – Our Stewards 47 Thank You! – Our Supporters 48 Who’s Who 50 The Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank production of Twelfth Night. Photo: Cesare de Giglio The Little Matchgirl and Other Happier Tales. Photo: Steve Tanner WELCOME 2016 – a momentous year – in which the world celebrated the richness of Shakespeare’s legacy 400 years after his death. Shakespeare’s Globe is proud to have played a part in those celebrations in 197 countries and led the festivities in London, where Shakespeare wrote and worked. Our Globe to Globe Hamlet tour travelled 193,000 miles before coming home for a final emotional performance in the Globe to mark the end, not just of this phenomenal worldwide journey, but the artistic handover from Dominic Dromgoole to Emma Rice. A memorable season of late Shakespeare plays in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and two outstanding Globe transfers in the West End ran concurrently with the last leg of the Globe to Globe Hamlet tour. On Shakespeare’s birthday, 23 April, we welcomed President Obama to the Globe. Actors performed scenes from the late plays running in the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse at Southwark Cathedral, a service which was the only major civic event to mark the anniversary in London and was attended by our Patron, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E. -

March 2016 Conversation

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA ENGAGING PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD IN COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE WNDC IN WASHINGTON THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION DIANA OWEN ♦ Tuesday, February 23 As we commemorate SHAKESPEARE 400, a global celebration of the poet’s life and legacy, the GUILD is delighted to co-host a WOMAN’S NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC CLUB gathering with DIANA OWEN, who heads the SHAKESPEARE BIRTHPLACE TRUST in Stratford-upon-Avon. The TRUST presides over such treasures as Mary Arden’s House, WITTEMORE HOUSE Anne Hathaway’s Cottage, and the home in which the play- 1526 New Hampshire Avenue wright was born. It also preserves the site of New Place, the Washington mansion Shakespeare purchased in 1597, and in all prob- LUNCH 12:30. PROGRAM 1:00 ability the setting in which he died in 1616. A later owner Luncheon & Program, $30 demolished it, but the TRUST is now unearthing the struc- Program Only , $10 ture’s foundations and adding a new museum to the beautiful garden that has long delighted visitors. As she describes this exciting project, Ms. Owen will also talk about dozens of anniversary festivities, among them an April 23 BBC gala that will feature such stars as Dame Judi Dench and Sir Ian McKellen. PEGGY O’BRIEN ♦ Wednesday, February 24 Shifting to the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY, an American institution that is marking SHAKESPEARE 400 with a national tour of First Folios, we’re pleased to welcome PEGGY O’BRIEN, who established the Library’s globally acclaimed outreach initiatives to teachers and NATIONAL ARTS CLUB students in the 1980s and published a widely circulated 15 Gramercy Park South Shakespeare Set Free series with Simon and Schuster. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Favourite Poems for Children Favourite Poems For

Favourite Poems JUNIOR CLASSICS for Children The Owl and the Pussycat • The Pied Piper of Hamelin The Jumblies • My Shadow and many more Read by Anton Lesser, Roy McMillan, Rachel Bavidge and others 1 The Lobster Quadrille Lewis Carroll, read by Katinka Wolf 1:58 2 The Walrus and the Carpenter Lewis Carroll, read by Anton Lesser 4:22 3 You Are Old, Father William Lewis Carroll, read by Roy McMillan 1:46 4 Humpty Dumpty’s Song Lewis Carroll, read by Richard Wilson 2:05 5 Jabberwocky Lewis Carroll, read by David Timson 1:33 6 Little Trotty Wagtail John Clare, read by Katinka Wolf 0:51 7 The Bogus-Boo James Reeves, read by Anton Lesser 1:17 8 A Tragedy in Rhyme Oliver Herford, read by Anton Lesser 2:25 9 A Guinea Pig Song Anonymous, read by Katinka Wolf 0:47 10 The Jumblies Edward Lear, read by Anton Lesser 4:06 2 11 The Owl and the Pussycat Edward Lear, read by Roy McMillan 1:35 12 Duck’s Ditty Kenneth Grahame, read by Katinka Wolf 0:40 13 There was an Old Man with a Beard Edward Lear, read by Roy McMillan 0:17 14 Old Meg John Keats, read by Anne Harvey 1:24 15 How Pleasant to Know Mr Lear Edward Lear, read by Roy McMillan 1:31 16 There was a naughty boy John Keats, read by Simon Russell Beale 0:35 17 At the Zoo William Makepeace Thackeray, read by Roy McMillan 0:29 18 Dahn the Plug’ole Anonymous, read by Anton Lesser 1:14 19 Henry King Hilaire Belloc, read by Katinka Wolf 0:47 20 Matilda Hilaire Belloc, read by Anne Harvey 2:35 3 21 The King’s Breakfast A.A. -

A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and Its Development Into the Young Writers’ Programme

Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme N O Holden Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Building the Engine Room: A Study of the Royal Court’s Young Peoples’ Theatre and its Development into the Young Writers’ Programme Nicholas Oliver Holden, MA, AKC A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Fine and Performing Arts College of Arts March 2018 2 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for a higher degree elsewhere. 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisors: Dr Jacqueline Bolton and Dr James Hudson, who have been there with advice even before this PhD began. I am forever grateful for your support, feedback, knowledge and guidance not just as my PhD supervisors, but as colleagues and, now, friends. Heartfelt thanks to my Director of Studies, Professor Mark O’Thomas, who has been a constant source of support and encouragement from my years as an undergraduate student to now as an early career academic. To Professor Dominic Symonds, who took on the role of my Director of Studies in the final year; thank you for being so generous with your thoughts and extensive knowledge, and for helping to bring new perspectives to my work. My gratitude also to the University of Lincoln and the School of Fine and Performing Arts for their generous studentship, without which this PhD would not have been possible. -

Catrin Meredydd Production Designer

Catrin Meredydd Production Designer Winner of BAFTA Cymru award for Best Production Design 2017 for Damilola, Our Loved Boy. Winner of BAFTA Cymru award for Best Production Design 2019 for Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Agents Madeleine Pudney Assistant 020 3214 0999 Eliza McWilliams [email protected] 020 3214 0999 Daniela Manunza Assistant [email protected] Lizzie Quinn [email protected] + 44 (0) 203 214 0911 Credits In Development Production Company Notes CHASING AGENT Great Point Media / Rabbit Track Dirs: Declan Lawn & Adam FREEGARD Pictures / The Development Partnership Patterson 2021 Prods: Michael Bronner, Kitty Kaletsky & Robert Taylor SOULMATES 2 AMC / Amazon Postponed 2020 Film Production Company Notes United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] MRS LOWRY AND SON Genesius Pictures Dir: Adrian Noble Prod: Debbie Gray Period Drama 1930's Starring Vanessa Redgrave & Timothy 2019 Spall IBOY Wigwam Films/ Pretty Dir: Adam Randall Pictures Prods: Lucan Toh, Oliver Roskill, Emily Leo, Contemporary Gail Mutrux 2016 With Bill Milner, Rory Kinnear, Miranda Richardson, Maisie Williams BELIEVE Bill and Ben Productions Dir: David Scheinmann Prods: Manuela Noble, Ben Timlett 1950's/1980's With Brian Cox, Toby Stephens, Natascha 2013 McElhone Television Production Company Notes CURSED Netflix Dirs: Jon East, Zetna Fuentes, Daniel Nettheim and Sarah O'Gorman 10 x 60 Medieval Drama Showrunners: Tom Wheeler and Frank Miller 2019