Dd Shrewstudyguide.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shakespeare Othello Mp3, Flac, Wma

Shakespeare Othello mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Non Music / Stage & Screen Album: Othello Country: US Style: Spoken Word MP3 version RAR size: 1178 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1926 mb WMA version RAR size: 1908 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 984 Other Formats: MP1 VOC MP2 WMA MP3 DMF AAC Tracklist A Othello B Othello Companies, etc. Recorded By – F.C.M. Productions Published By – Worlco Credits Composed By [Musique Concrete], Composed By [Sound Patterns] – Desmond Leslie Directed By – Michael Benthall Voice Actor [Brabantio] – Ernest Hare Voice Actor [Cassio] – John Humphry Voice Actor [Desdemona] – Barbara Jefford Voice Actor [Duke Of Venice] – Charles West Voice Actor [Emilia] – Coral Browne Voice Actor [Iago] – Ralph Richardson Voice Actor [Lodovico, Senator] – Joss Ackland Voice Actor [Narrator] – Michael Benthall Voice Actor [Othello] – John Gielgud Voice Actor [Sailor] – Stephen Moore Voice Actor [Senator] – David Tudor-Jones Voice Actor [Small Part] – David Lloyd-Meredith, Peter Ellis , Roger Grainger Written-By – William Shakespeare Notes Modern abridged version. An F.C.M. production. Includes a 16 page booklet. Australian WRC 2nd pressing, sourced from original stampers and featuring unique sleeve art. Same sleeve design as previous issue, except new addresses. The mono version has a red sticker with "mono" on the back (though these tend to drop off with age). "SLS-4" on labels, "LS/4" on sleeve. 299 Flinders Lane Melbourne 177 Elizabeth St Sydney Newspaper House, 93 Queen St Brisbane 60 Pulteney St Adelaide Barnett's Building, Council Ave Perth Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year William Othello (LP, Oldbourne Press, DEOB 3AS DEOB 3AS UK 1964 Shakespeare Album) Odhams Books Ltd. -

Actors and Accents in Shakespearean Performances in Brazil: an Incipient National Theater1

Scripta Uniandrade, v. 15, n. 3 (2017) Revista da Pós-Graduação em Letras – UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil ACTORS AND ACCENTS IN SHAKESPEAREAN PERFORMANCES IN BRAZIL: AN INCIPIENT NATIONAL THEATER1 DRA. LIANA DE CAMARGO LEÃO Universidade Federal do Paraná (UFPR) Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil ([email protected]) DRA. MAIL MARQUES DE AZEVEDO Centro Universitário Campos de Andrade, UNIANDRADE Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT: The main objective of this work is to sketch a concise panorama of Shakespearean performances in Brazil and their influence on an incipient Brazilian theater. After a historical preamble about the initial prevailing French tradition, it concentrates on the role of João Caetano dos Santos as the hegemonic figure in mid nineteenth-century theatrical pursuits. Caetano’s memorable performances of Othello, his master role, are examined in the theatrical context of his time: parodied by Martins Pena and praised by Machado de Assis. References to European companies touring Brazil, and to the relevance of Paschoal Carlos Magno’s creation of the TEB for a theater with a truly Brazilian accent, lead to final succinct remarks about the twenty-first century scenery. Keywords: Shakespeare. Performances. Brazilian Theater. Artigo recebido em 13 out. 2017. Aceito em 11 nov. 2017. 1 This paper was first presented at the World Shakespeare Congress 2016 of the International Shakespeare Association, in Stratford-upon-Avon. LEÃO, Liana de Camargo; AZEVEDO, Mail Marques de. Actors and accents in Shakespearean performances in Brazil: An incipient national theater. Scripta Uniandrade, v. 15, n. 3 (2017), p. 32-43. Curitiba, Paraná, Brasil Data de edição: 11 dez. -

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015 -16 the RSC Acting Companies Are Generously Supported by the GATSBY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION and the KOVNER FOUNDATION

ANNUAL REVIEW 2015 -16 The RSC Acting Companies are generously supported by THE GATSBY CHARITABLE FOUNDATION and THE KOVNER FOUNDATION. Hugh Quarshie and Lucian Msamati in Othello. 2015/16 has been a blockbuster year for Shakespeare and for the RSC. 400th anniversaries do not happen often and we wanted to mark 2016 with an unforgettable programme to celebrate Shakespeare’s extraordinary legacy and bring his work to a whole new generation. Starting its life in Stratford-upon-Avon, Tom Morton-Smith about Oppenheimer, we staged A Midsummer Night’s a revival of Miller’s masterpiece Dream in every nation and region Death of a Salesman, marking his of the UK, with 84 amateurs playing centenary, and the reopening of Bottom and the Mechanicals and The Other Place, our new creative over 580 schoolchildren as Titania’s hub. Our wonderful production of fairy train. This magical production Matilda The Musical continued on has touched the lives of everyone its life-enhancing journey, playing involved and we are hugely grateful on three continents to an audience to our partner theatres, schools and of almost 2 million. the amateur companies for making this incredible journey possible. Our work showcased the fabulous range of diverse talent from across We worked in partnership with the the country, and we are proud of the BBC to bring ‘Shakespeare Live! From increasing diversity of our audiences. the RSC’ to a television audience of 1.6m and to cinema audiences in People sometimes ask if Shakespeare 15 countries. The glittering cast is still relevant. The response from performed in the Royal Shakespeare audiences everywhere has been a Theatre to an audience drawn from resounding ‘yes’. -

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV

Broadcasting the Arts: Opera on TV With onstage guests directors Brian Large and Jonathan Miller & former BBC Head of Music & Arts Humphrey Burton on Wednesday 30 April BFI Southbank’s annual Broadcasting the Arts strand will this year examine Opera on TV; featuring the talents of Maria Callas and Lesley Garrett, and titles such as Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) and The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), this season will show how television helped to democratise this art form, bringing Opera into homes across the UK and in the process increasing the public’s understanding and appreciation. In the past, television has covered opera in essentially four ways: the live and recorded outside broadcast of a pre-existing operatic production; the adaptation of well-known classical opera for remounting in the TV studio or on location; the very rare commission of operas specifically for television; and the immense contribution from a host of arts documentaries about the world of opera production and the operatic stars that are the motor of the industry. Examples of these different approaches which will be screened in the season range from the David Hockney-designed The Magic Flute (Southern TV/Glyndebourne, 1978) and Luchino Visconti’s stage direction of Don Carlo at Covent Garden (BBC, 1985) to Peter Brook’s critically acclaimed filmed version of The Tragedy of Carmen (Alby Films/CH4, 1983), Jonathan Miller’s The Mikado (Thames/ENO, 1987), starring Lesley Garret and Eric Idle, and ENO’s TV studio remounting of Handel’s Julius Caesar with Dame Janet Baker. Documentaries will round out the experience with a focus on the legendary Maria Callas, featuring rare archive material, and an episode of Monitor with John Schlesinger’s look at an Italian Opera Company (BBC, 1958). -

J Ohn F. a Ndrews

J OHN F . A NDREWS OBE JOHN F. ANDREWS is an editor, educator, and cultural leader with wide experience as a writer, lecturer, consultant, and event producer. From 1974 to 1984 he enjoyed a decade as Director of Academic Programs at the FOLGER SHAKESPEARE LIBRARY. In that capacity he redesigned and augmented the scope and appeal of SHAKESPEARE QUARTERLY, supervised the Library’s book-publishing operation, and orchestrated a period of dynamic growth in the FOLGER INSTITUTE, a center for advanced studies in the Renaissance whose outreach he extended and whose consortium grew under his guidance from five co-sponsoring universities to twenty-two, with Duke, Georgetown, Johns Hopkins, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Penn, Penn State, Princeton, Rutgers, Virginia, and Yale among the additions. During his time at the Folger, Mr. Andrews also raised more than four million dollars in grant funds and helped organize and promote the library’s multifaceted eight- city touring exhibition, SHAKESPEARE: THE GLOBE AND THE WORLD, which opened in San Francisco in October 1979 and proceeded to popular engagements in Kansas City, Pittsburgh, Dallas, Atlanta, New York, Los Angeles, and Washington. Between 1979 and 1985 Mr. Andrews chaired America’s National Advisory Panel for THE SHAKESPEARE PLAYS, the BBC/TIME-LIFE TELEVISION canon. He then became one of the creative principals for THE SHAKESPEARE HOUR, a fifteen-week, five-play PBS recasting of the original series, with brief documentary segments in each installment to illuminate key themes; these one-hour programs aired in the spring of 1986 with Walter Matthau as host and Morgan Bank and NEH as primary sponsors. -

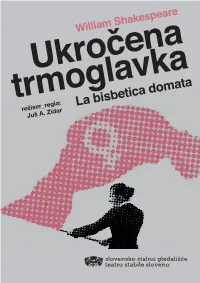

Gledališki List Uprizoritve

1 Na vest, da vam je boljše, so prišli z vedro komedijo vaši igralci; zdravniki so tako priporočili: preveč otožja rado skrkne kri, čemernost pa je pestunja blaznila. Zato da igra vam lahko le hasne; predajte se veselju; kratkočasje varje pred hudim in življenje daljša. William Shakespeare, UKROČENA TRMOGLAVKA 2 3 4 5 William Shakespeare Ukročena trmoglavka La bisbetica domata avtorji priredbe so ustvarjalci uprizoritve adattamento a cura della compagnia režiser/ regia: Juš A. Zidar prevajalec/ traduzione: Milan Jesih dramaturginja/ dramaturg: Eva Kraševec scenografinja/ scene:Petra Veber kostumografinja/ costumi:Mateja Fajt avtor glasbe/ musiche: Jurij Alič lektorica/ lettore: Tatjana Stanič asistent dramaturgije/ assistente dramaturg: Sandi Jesenik Igrajo/ Con: Iva Babić Tadej Pišek Zdravniki so tako priporočili: Vladimir Jurc Tina Gunzek preveč otožja rado skrkne kri, Jernej Čampelj Ilija Ota čemernost pa je pestunja blaznila. Andrej Rismondo Vodja predstave in rekviziterka/ Direttrice di scena e attrezzista Sonja Kerstein Lo raccomandano i medici: Tehnični vodja/ Direttore tecnico Peter Furlan Tonski mojster/ Fonico Diego Sedmak l’amarezza ha congelato Lučni mojster/ Elettricista Peter Korošic Odrski mojster/ Capo macchinista Giorgio Zahar il vostro sangue e la malinconia Odrski delavec/ Macchinista Marko Škabar, Dejan Mahne Kalin Garderoberka in šivilja/ Guardarobiera Silva Gregorčič è nutrice di follia. Prevajalka in prirejevalka nadnapisov/ Traduzione e adattamento sovratitoli Tanja Sternad Šepetalka in nadnapisi/ Suggeritrice e sovratitoli Neda Petrovič Premiera: 16. marca 2018/ Prima: 16 marzo 2018 Velika dvorana/ Sala principale 6 prvih del (okoli leta 1592) odločil, da bo obravnaval ravno t.i. žensko In živela sta srčno esej 01 vprašanje, odnos, ki so ga imeli moški do žensk v elizabetinski družbi, še posebno v pojmovanju inštitucije poroke. -

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

TREFOR PROUD Make-Up Artist IATSE 706 Journeyman Member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences FILM MR. CHURCH Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Britt Robertson, Xavier Samuel, Christian Madsen SPY Make-Up Department Head Director: Paul Feig Cast: Jason Statham, Rose Byrme, Peter Serafinowicz, Julian Miller THE PURGE 2 - ANARCHY Make-Up Department Head and Mask Design Director: James DeMonaco Cast: Michael K. Williams, Frank Grillo, Carmen Ejogo BONNIE AND CLYDE Make-Up Department Head Director: Bruce Beresford Cast: Emile Hirsch, Holly Hunter, William Hurt, Sarah Hyland Nominee: Emmy – Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or a Movie (Non-Prosthetic) ENDER’S GAME Make-Up Department Head Director: Gavin Hood Cast: Harrison Ford, Asa Butterfield, Sir Ben Kingsley JACK REACHER Make-Up Department Head Director: Christopher McQuarrie Cast: Rosamund Pike, Robert Duvall THE RITE Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Mikael Håfström Cast: Alice Braga, Anthony Hopkins, Ciarán Hinds A NIGHTMARE ON ELM STREET Department Head Make-Up, Los Angeles Director: Samuel Bayer Cast: Jackie Earle Hayley, Kyle Gallner, Rooney Mara, Katie Cassidy, Thomas Dekker, Kellan Lutz, Clancy Brown LONDON DREAMS Make-Up and Hair Designer Director: Vipul Amrutlal Shah Cast: Salman Khan, Ajay Devgan, Asin, THE COURAGEOUS HEART Make-Up and Hair Department Head OF IRENA SENDLER Director: John Kent Harrison Hallmark Hall of Fame Cast: Anna Paquin, Goran Visnjic, Marcia Gay Harden Winner: Emmy for Outstanding Make-Up for a Miniseries or Movie -

Text Pages Layout MCBEAN.Indd

Introduction The great photographer Angus McBean has stage performers of this era an enduring power been celebrated over the past fifty years chiefly that carried far beyond the confines of their for his romantic portraiture and playful use of playhouses. surrealism. There is some reason. He iconised Certainly, in a single session with a Yankee Vivien Leigh fully three years before she became Cleopatra in 1945, he transformed the image of Scarlett O’Hara and his most breathtaking image Stratford overnight, conjuring from the Prospero’s was adapted for her first appearance in Gone cell of his small Covent Garden studio the dazzle with the Wind. He lit the touchpaper for Audrey of the West End into the West Midlands. (It is Hepburn’s career when he picked her out of a significant that the then Shakespeare Memorial chorus line and half-buried her in a fake desert Theatre began transferring its productions to advertise sun-lotion. Moreover he so pleased to London shortly afterwards.) In succeeding The Beatles when they came to his studio that seasons, acknowledged since as the Stratford he went on to immortalise them on their first stage’s ‘renaissance’, his black-and-white magic LP cover as four mop-top gods smiling down continued to endow this rebirth with a glamour from a glass Olympus that was actually just a that was crucial in its further rise to not just stairwell in Soho. national but international pre-eminence. However, McBean (the name is pronounced Even as his photographs were created, to rhyme with thane) also revolutionised British McBean’s Shakespeare became ubiquitous. -

Actors' Stories Are a SAG Awards® Tradition

Actors' Stories are a SAG Awards® Tradition When the first Screen Actors Guild Awards® were presented on March 8, 1995, the ceremony opened with a speech by Angela Lansbury introducing the concept behind the SAG Awards and the Actor® statuette. During her remarks she shared a little of her own history as a performer: "I've been Elizabeth Taylor's sister, Spencer Tracy's mistress, Elvis' mother and a singing teapot." She ended by telling the audience of SAG Awards nominees and presenters, "Tonight is dedicated to the art and craft of acting by the people who should know about it: actors. And remember, you're one too!" Over the Years This glimpse into an actor’s life was so well received that it began a tradition of introducing each Screen Actors Guild Awards telecast with a distinguished actor relating a brief anecdote and sharing thoughts about what the art and craft mean on a personal level. For the first eight years of the SAG Awards, just one actor performed that customary opening. For the 9th Annual SAG Awards, however, producer Gloria Fujita O'Brien suggested a twist. She observed it would be more representative of the acting profession as a whole if several actors, drawn from all ages and backgrounds, told shorter versions of their individual journeys. To add more fun and to emphasize the universal truths of being an actor, the producers decided to keep the identities of those storytellers secret until they popped up on camera. An August Lineage Ever since then, the SAG Awards have begun with several of these short tales, typically signing off with his or her name and the evocative line, "I Am an Actor™." So far, audiences have been delighted by 107 of these unique yet quintessential Actors' Stories. -

"A Midsummer Night's Dream" at Eastman Thratre; Jan. 21

of the University of Rochester Walter Hendl, Director presents THE EASTMAN OPERA THEATRE's PRODUCTION of A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from William Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears LEONARD TREASH, Director EDWIN McARTHUR, Conductor THOMAS STRUTHERS, Designer Friday Evening, January 21, 1972, at 8:15 Saturday Evening, January 22, 1972, at 8:15 CAST (in order of appearance) Friday, January 21 Saturday, January 22 Cobweb Robin Eaton Robin Eaton Pease blossom Candace Baranowski Candace Baranowski Mustardseed Janet Obermeyer Janet Obermeyer Moth Doreen DeFeis Doreen DeFeis Puck Larry Clark Larry Clark Oberon Letty Snethen Laura Angus Tytania Judith Dickison Sharon Harrison Lysander Booker T. Wilson Bruce Bell Hermia Mary Henderson Maria Floros Demetrius Ralph Griffin Joseph Bias Helena Cecile Saine Julianne Cross Quince James Courtney James Courtney Flute Carl Bickel David Bezona Snout Bruce Bell Edward Pierce Starveling Tonio DePaolo Tonie DePaolo Bottom Alexander Stephens Alexander Stephens Snug Dan Larson Dan Larson Theseus Fredric Griesinger Fredric Griesinger Hippolyta '"- Laura Angus Letty Snethen Fairy Chorus: Edwin Austin, Steven Bell, Mark Cohen, Thomas Johnson, William McNeice, Gregory Miller, John Miller, Swan Oey, Gary Pentiere, Jeffrey Regelman, James Singleton, Marc Slavny, Thomas Spittle, Jeffrey VanHall, Henry Warfield, Kevin Weston. (Members of the Eastman Childrens Chorus, Milford Fargo, Conductor) . ' ~ --· .. - THE STORY Midsummer Night's Dream, Its Sources, Its Construction, -

Contemporary Opera Studio Presents "Socrates", "Christopher Sly"

Contemporary Opera Studio presents "Socrates", "Christopher Sly" April 7, 1972 Contemporary Opera Studio, developed jointly by the San Diego Opera Company and the University of California, San Diego, will present a double-bill program of "Socrates" by Erik Satie and the comic "Christopher Sly" by Dominick Argento on Friday and Saturday, April 21 and 22. To be held in the recently opened UCSD Theatre, Bldg. 203 an the Matthews Campus, the two performances will begin at 8:30 p.m. Tickets are $2.00 for general admission and $1.00 for students. The Opera Studio was formed in the winter of 1971 to perform unusual works, and innovative productions of standard works, which, because of their unusual nature, could not be profitably performed by the main opera company. The developers of this experimental wing of the downtown opera company hope it will become a training school, emphasizing the theatrical aspects of opera, for young professional singers. The two operas to be performed make use of a wide range of acting techniques and musical effects demonstrated in acting and movement classes of the Opera Studio. "Socrates," written in 1918, is a "symphonic drama" based on texts translated from Plato's "Dialogues." The opera is unusual in that women take the roles of Socrates and his companions. Director of "Socrates" is Mary Fee. Double cast in the role of Socrates are Beverly Ogdon and Cathy Campbell. Erik Satie, composer of "Socrates", is was very much a part of the artistic life of Paris near the beginning of the 20th century. His friends included Debussy, Ravel, Cocteau, and Picasso. -

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional Events

English 252: Theatre in England 2006-2007 * [Optional events — seen by some] Wednesday December 27 *2:30 p.m. Guys and Dolls (1950). Dir. Michael Grandage. Music & lyrics by Frank Loesser, Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. Based on a story and characters of Damon Runyon. Designer: Christopher Oram. Choreographer: Rob Ashford. Cast: Alex Ferns (Nathan Detroit), Samantha Janus (Miss Adelaide), Amy Nuttal (Sarah Brown), Norman Bowman (Sky Masterson), Steve Elias (Nicely Nicely Johnson), Nick Cavaliere (Big Julie), John Conroy (Arvide Abernathy), Gaye Brown (General Cartwright), Jo Servi (Lt. Brannigan), Sebastien Torkia (Benny Southstreet), Andrew Playfoot (Rusty Charlie/ Joey Biltmore), Denise Pitter (Agatha), Richard Costello (Calvin/The Greek), Keisha Atwell (Martha/Waitress), Robbie Scotcher (Harry the Horse), Dominic Watson (Angie the Ox/MC), Matt Flint (Society Max), Spencer Stafford (Brandy Bottle Bates), Darren Carnall (Scranton Slim), Taylor James (Liverlips Louis/Havana Boy), Louise Albright (Hot Box Girl Mary-Lou Albright), Louise Bearman (Hot Box Girl Mimi), Anna Woodside (Hot Box Girl Tallulha Bloom), Verity Bentham (Hotbox Girl Dolly Devine), Ashley Hale (Hotbox Girl Cutie Singleton/Havana Girl), Claire Taylor (Hot Box Girl Ruby Simmons). Dance Captain: Darren Carnall. Swing: Kate Alexander, Christopher Bennett, Vivien Carter, Rory Locke, Wayne Fitzsimmons. Thursday December 28 *2:30 p.m. George Gershwin. Porgy and Bess (1935). Lyrics by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin. Book by Dubose and Dorothy Heyward. Dir. Trevor Nunn. Design by John Gunter. New Orchestrations by Gareth Valentine. Choreography by Kate Champion. Lighting by David Hersey. Costumes by Sue Blane. Cast: Clarke Peters (Porgy), Nicola Hughes (Bess), Cornell S. John (Crown), Dawn Hope (Serena), O-T Fagbenie (Sporting Life), Melanie E.