Thaddeus Strassberger Multiple Mythologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

January 11, 2021 in Accordance with Section 2Ofthe Confirmation Act

MURIEL BOWSER MAYOR January 11, 2021 The Honorable Phil Mendelson Chairman Council of the District of Columbia John A. Wilson Building 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Suite 504 Washington, DC 20004 Dear Chairman Mendelson: In accordance with section 2 of the Confirmation Act of 1978, effective March 3, 1979 (D.C. Law 2-142; D.C. Official Code § 1-523.01), and pursuant to section 305 of the Fiscal Year 2002 Budget Support Act of 2001, effective October 3, 2001 (D.C. Law 14-28; D.C. Official Code § 2-1374), which established the Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander Community Development (“Commission”), I am pleased to nominate the following person: Mr. John Tinpe 7th Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 (Ward 2) for reappointment as a public voting member of the Commission, fora term to end April 17, 2022. Enclosed, you will find biographical information detailing the experience of the above-mentioned nominee, together with a proposed resolution to assist the Council during the confirmation process. 1 would appreciate the Council’s earliest consideration of this nomination for confirmation. Please do not hesitate to contact me, or Steven Walker, Director, Mayor's Office of Talent and Appointments, should the Council require additional information. Sincerely, Mutiel Bolyser fle Hreee— Chairman Phil Mendelson at the request of the Mayor A PROPOSED RESOLUTION IN THE COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA To confirm the reappointment of Mr. John Tinpe to the Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander Community Development. RESOLVED, BY THE COUNCIL OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA, That this resolution may be cited as the “Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander Community Development John Tinpe Confirmation Resolution of 2021”. -

Jahresbericht 2014 Richard Wagner Verband Regensburg E.V

Richard Wagner Verband Regensburg e.V. ************************************************************************* Emil Kerzdörfer, 1. Vorsitzender Kaiser - Friedrich - Allee 46 D - 93051 Regensburg Tel: (+49)-941-95582 Fax: (+49)-941-92655 www.Richard-Wagner-Verband -Regensburg.de **************************************************************************************** Motto: „… der Komponist offenbart das innerste Wesen der Welt und spricht die tiefste Weisheit aus, in einer Sprache, die seine Vernunft nicht versteht“. Artur Schopenhauer (1788 -1860) ****************************************************************************************** Jahresbericht 2014 gewidmet unserem Ehrenmitglied Frau Verena Lafferentz-Wagner 1. Vorsitzender: Emil Kerzdörfer Mitgliederzahl: 463 01. Januar: Opernbesuch im Theater Regensburg Richard Wagner: Die Feen, Premiere Romantische Oper in drei Akten Regensburger Erstaufführung Inszenierung: Florian Lutz Dirigent: Tetsuro Ban 05. Februar: Jour Fixe im Kolpinghaus Multimediavortrag: Emil Kerzdörfer: „Giuseppe Verdis Requiem“ 07. Februar: Konzertfahrt nach München in die Philharmonie Giuseppe Verdi: „Messa da Requiem“ Solisten: Anja Harteros (Sopran) Daniela Barcellona (Alt ) Woukyung Kim (Tenor) Georg Zeppenfeld (Bass) Münchner Philharmoniker Philharmonischer Chor München Dirigent: Lorin Maazel 26. Februar: Konzertfahrt nach München in die Philharmonie Jean Sibelius: Valse Triste, op. 44 Sergej Prokofieff: Konzert für Klavier und Orchester, Nr. 3, C-Dur, op. 26 Robert Schumann: Symphonie Nr. 4, d-moll, op. -

S I N G L E T I C K E T B R O C H U

2013-2014 SEASON SINGLE TICKET BROCHURE MOURNING BECOMES ELECTRA NABUCCO TOSCA THAÏS Mourning Becomes Electra Nabucco Welcome! You don’t want to miss our upcoming season. Where else can you travel from Ancient Babylon to post Civil War New England without leaving South Florida, while enjoying some of the finest singers and exciting productions from around the world. If you are new to opera, the themes of these pieces will resonate with you Tosca regardless of which of the many diverse communities of South Florida you call home. This season has something for everyone. See You at the Opera, Susan T. Danis Ramón Tebar General Director and CEO Music Director Thaïs NOV 07/ NOV 23 NABUCCO JAN 25/ FEB 08 MOURNING BECOMES NABUCCO ELECTRA BY GIUSEPPE VERDI BY MARVIN DAVID LEVY “It’s got everything you’d want from an opera…and more. “…When I am alone with my notes, my heart pounds and the The music knocks you out with its ferocity.” -- Marvin David Levy tears stream from my eyes, and my emotion and my joys are too much to bear.” -- Giuseppe Verdi Nabucco © Scott Suchman for Washington National Opera. BasedMourning on Becomes the play Electra cycle © Rozarii by Eugene Lynch for Seattle O’Neill, Opera. this mythic tale is set in Massachusetts shortly This opera captures the voice of the ancient Hebrews and their struggle as exiles. In fact, it speaks after the Civil War. Beneath the veneer of the prim and proper Mannon family are seething with the voice of all exiles. Experience the anguish as Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylonia, destroys passions of bitterness, infidelity, incest, and even murder. -

Network Notebook

Network Notebook Summer Quarter 2019 (July - September) A World of Services for Our Affiliates We make great radio as affordable as possible: • Our production costs are primarily covered by our arts partners and outside funding, not from our affiliates, marketing or sales. • Affiliation fees only apply when a station takes three or more programs. The actual affiliation fee is based on a station’s market share. Affiliates are not charged fees for the selection of WFMT Radio Network programs on the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). • The cost of our Beethoven and Jazz Network overnight services is based on a sliding scale, depending on the number of hours you use (the more hours you use, the lower the hourly rate). We also offer reduced Beethoven and Jazz Network rates for HD broadcast. Through PRX, you can schedule any hour of the Beethoven or Jazz Network throughout the day and the files are delivered a week in advance for maximum flexibility. We provide highly skilled technical support: • Programs are available through the Public Radio Exchange (PRX). PRX delivers files to you days in advance so you can schedule them for broadcast at your convenience. We provide technical support in conjunction with PRX to answer all your distribution questions. In cases of emergency or for use as an alternate distribution platform, we also offer an FTP (File Transfer Protocol), which is kept up to date with all of our series and specials. We keep you informed about our shows and help you promote them to your listeners: • Affiliates receive our quarterly Network Notebook with all our program offerings, and our regular online WFMT Radio Network Newsletter, with news updates, previews of upcoming shows and more. -

Les Deux Foscari /Giuseppe Verdi

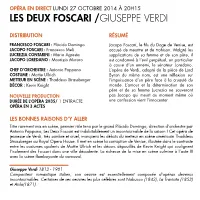

OPÉRA EN DIRECT LUNDI 27 OCTOBRE 2014 À 20H15 LES DEUX FOSCARI /GIUSEPPE VERDI DISTRIBUTION RÉSUMÉ FRANCESCO FOSCARI : Plácido Domingo Jacopo Foscari, le fils du Doge de Venise, est JACOPO FOSCARI : Francesco Meli accusé de meurtre et de trahison. Malgré les LUCREZIA CONTARINI : Maria Agresta supplications de sa femme et de son père, il JACOPO LOREDANO : Maurizio Muraro est condamné à l’exil perpétuel, en particulier à cause d’un ennemi, le sénateur Loredano. CHEF D’ORCHESTRE : Antonio Pappano L’opéra de Verdi, adapté de la pièce de Lord COSTUME : Mattie Ullrich Byron du même nom, est une réflexion sur METTEUR EN SCÈNE : Thaddeus Strassberger l’impuissance d’un père face à la cruauté du DÉCOR : Kevin Knight monde. L’amour et la détermination de son père et de sa femme Lucrezia ne sauveront NOUVELLE PRODUCTION pas Jacopo qui meurt au moment même où DURÉE DE L’OPÉRA 2H35/ 1 ENTRACTE une confession vient l’innocenter. OPÉRA EN 3 ACTES LES BONNES RAISONS D’Y ALLER Titre rarement mis en scène, premier rôle tenu par le grand Plácido Domingo, direction d’orchestre par Antonio Pappano, Les Deux Foscari est indubitablement un incontournable de la saison ! Cet opéra de jeunesse de Verdi, très sombre et cruel, marquera les débuts du metteur en scène américain Thaddeus Strassberger au Royal Opera House. Il met en scène la corruption de Venise, illustrée dans le contraste entre les costumes opulents de Mattie Ullrich et les décors dépouillés de Kevin Knight qui soulignent l’isolement des Foscari dans une ville décadente. La richesse de la mise en scène culmine à l’acte III avec la scène flamboyante du carnaval. -

The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College

the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college THEEthel Smyth’s WRECKERS July 24 – August 2, 2015 About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic President Leon Botstein presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. presents Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space, and in the 220-seat LUMA Theater, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater & Performance and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrated its 25th year last August with “Schubert and His World.” The 2015 festival will be devoted to Carlos Chávez and the music of Mexico and the rest of Latin America. THE The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support WRECKERS and welcome all donations. By Ethel Smyth Director Thaddeus Strassberger American Symphony Orchestra Conductor Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design Erhard Rom Costume Design Kaye Voyce Lighting Design JAX Messenger Projection Design Hannah Wasileski Hair and Makeup Design J. -

Nabucco’, De Verdi, Amb Plácido Domingo En El Paper Protagonista

Les Arts és Òpera Les Arts estrena ‘Nabucco’, de Verdi, amb Plácido Domingo en el paper protagonista Jordi Bernàcer assumeix la direcció musical d’aquesta òpera que es presenta en un muntatge de Thaddeus Strassberger Les entrades estan esgotades excepte el cinc per cent de l’aforament que es reserva per a la seua venda el mateix dia de cada representació València (29.11.19). El Palau de les Arts estrena aquest pròxim dilluns, 2 de desembre, a les 20.00 hores, l’òpera ‘Nabucco’, considerada com el primer gran èxit de Giuseppe Verdi. El valencià Jordi Bernàcer és el director musical d’aquest títol, que es presenta en un muntatge de Thaddeus Strassberger, amb Plácido Domingo en el paper protagonista per a les quatre primeres representacions. Jordi Bernàcer es retroba amb els cossos estables de les Arts, Cor de la Generalitat i Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana, amb els quals va iniciar la seua marxa professional, i assumeix per primera vegada la titularitat de totes les representacions d’una òpera d’abonament a les Arts. El mestre alcoià torna a la Sala Principal cinc anys després de les seues memorables funcions de la sarsuela ‘Luisa Fernanda’, també amb Plácido Domingo en el repartiment, en la temporada 2014-2015. En plena carrera internacional, i amb treballs per als teatres Mariinski de Sant Petersburg, Real de Madrid, San Carlo de Nàpols o Carlo Felice de Gènova, Jordi Bernàcer debutarà aquesta temporada amb l’Opéra Royal de Wallonie a Lieja, Petruzzelli de Bari, Semperoper de Dresden i Deutscheoper de Berlín, i tornarà a més a l’Òpera de San Francisco, Royal Opera House de Mascate, Òpera de Los Angeles, Òpera de Roma i Arena de Verona. -

Anton Rubinstein's

THE RICHARD B. FISHER CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT BARD COLLEGE Anton Rubinstein’s DEMON Sosnoff Theater July 27 – August 5, 2018 About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking perfor- President Leon Botstein mances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium- Executive Director Bob Bursey arch space, and in the 220-seat LUMA Theater, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater & Performance and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, film, and presents cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, celebrating its 29th year. Last year’s festival was “Chopin and His World”; the 2018 festival is devoted to the life and work of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. By Anton Rubinstein DEMONLibretto by Pavel Viskovatov (based on a poem by Mikhail Lermontov) Director Thaddeus Strassberger American Symphony Orchestra Conductor Leon Botstein, Music Director Bard Festival Chorale Chorus Master James Bagwell Pesvebi Georgian Dancers Choreographer Shorena Barbakadze Set Design Paul Tate dePoo III Costume Design Kaye Voyce Lighting Design JAX Messenger The 2018 Bard SummerScape season is made possible in part through the generous support Video Design Greg Emetaz of Jeanne Donovan Fisher, the Martin and Toni Sosnoff Foundation, the Board of The Richard B. -

Thaddeus Strassberger

Saverio Clemente Andrea De Amici Luca Targetti Thaddeus Strassberger began his career when he was awarded the prestigious European Opera Prize in 2005 for La Cenerentola (Opera Ireland/Hessisches Staatstheater Wiesbaden), having already earned a degree in Engineering from The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City; he received a Fulbright Fellowship to complete the Corso di Specializzazione per Scenografi Realizzatori at Teatro alla Scala in Milan in 2001. Notable first productions of his carrer include: Pique Dame (Tiroler Landestheater Innsbruck), Hamlet (Washington National Opera/Minnesota Opera/Fort Worth Opera/Lyric Opera of Kansas City), Nabucco (Washington National Opera/Minnesota Opera/Opera Philadelphia/Florida Grand Opera, Opera de Montreal), La Fanciulla del West (Opera de Montreal, Tiroler Landestheater Innsbruck), and Le nozze di Figaro and The rape of Lucretia (The Norwegian Opera). Thaddeus His production of I due foscari has recently been seen in Los Angeles and Valencia as well. His production ofthe rarely heard La Gazzetta Strassberger (Rossini in Wildbad Festival, Germany) garnered nominations for both Stage Director Best Production and Best Direction from Opernwelt magazine. In 2015, he returned to New York’s Bard SummerScape to direct Dame Ethyl Smyth's The Wreckers, his fifth production with the festival, previously having created productions of Les Huguenots, Der Ferne Klang, Le Roi Malgrè lui (co-produced with Wexford Festival), and his widely acclaimed production of Sergei Tanejev’s monumental opera, The Oresteia, the first staging of the neglected masterpiece to be seen outside of Russia. He returns to Staatstheater Braunschweig for a new Rigoletto, and directs and designs a world premiere of the opera Jfk by David T. -

Opera Program 7-13 RBF Program 4-16 2

the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college Emmanuel Chabrier’s The King in Spite of Himself July 27 – August 5, 2012 The Music Director, Musicians, and Staff of the American Symphony Orchestra dedicate these performances to the memory of Ronald Sell (1944–2012) Distinguished French horn player, member of the Orchestra for more than four decades, personnel manager, friend and colleague. His wisdom, grace, and humor will be missed. About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space, and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which fea- tures a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 23rd year in August with “Saint-Saëns and His World.” The 2013 festival will be devoted to Igor Stravinsky, with a special weekend focusing on the works of Duke Ellington. The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the con- tributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. -

MA's Free Guide to Free Streams, 4/15-21 by Clive Paget, Musical America April 15, 2020

15/04/2020 Printer-Friendly Receipt MA's Free Guide to Free Streams, 4/15-21 By Clive Paget, Musical America April 15, 2020 We will be updating this list weekly. Please note that British Summer Time (BST) is currently five hours ahead of U.S. Eastern Time (ET) and Central European Time (CET) is currently six hours ahead. Central Daylight Time (CDT) is currently one hour behind ET, while Pacific Time (PT) is currently three hours behind. Contact [email protected]. Wednesday, April 15 Noon CET: Staatsoper unter den Linden presents Prokofiev’s Betrothal in a Monastery. Conductor: Daniel Barenboim, director: Dmitri Tcherniakov with Aida Garifullina, Violeta Urmana, Anna Goryachova, Stephan Rügamer, Andrei Zhilikhovsky, Goran Juric, Bogdan Volkov, Lauri Vasar, Staatsopernchor, Staatskapelle Berlin. Available free for 24 hours. 4 pm CET: Concertgebouworkest streams Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker conducted by Semyon Bychkov with an introduction by Jörgen van Rijen (principal trombone). View on YouTube, Facebook or website. 5 pm CET: Vienna Staatsoper streams Wagner’s Parsifal (performance of April 21, 2019). Conductor: Valery Gergiev, director: Alvis Hermanis, with Thomas Johannes Mayer (Amfortas), René Pape (Gurnemanz), Simon O’Neill (Parsifal), Boaz Daniel (Klingsor), Elena Zhidkova (Kundry). Sign up for free and view here. 6 pm CET: Staatskapelle Dresden presents Busoni’s Lustspielouvertüre, Brahms’s Piano Concerto No. 2 and Brahms’s Symphony No. 2 conducted by Christian Thielemann with Maurizio Pollini, piano. View here and available for 48 hours. 12 pm ET: American Symphony Orchestra presents Bard SummerScape’s production of Rubinstein’s Demon. Conducted by Leon Botstein, directed by Thaddeus Strassberger. -

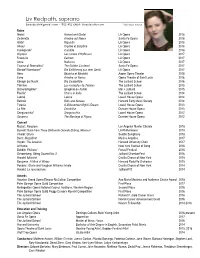

Liv Redpath, Soprano

Liv Redpath, soprano [email protected] · 952-452-6464 · livredpath.com *denotes cover Roles Gretel Hansel and Gretel LA Opera 2018 Zerbinetta Ariadne auf Naxos Santa Fe Opera 2018 Gilda* Rigoletto LA Opera 2018 Amour Orphée et Eurydice LA Opera 2018 Cunégonde* Candide LA Opera 2018 Olympia Les contes d’Hoffmann LA Opera 2017 Frasquita Carmen LA Opera 2017 Anna Nabucco LA Opera 2017 Tsarina of Shemakha* The Golden Cockerel Santa Fe Opera 2017 Blonde*/Konstanze* Die Entführung aus dem Serail LA Opera 2017 Héro Béatrice et Bénédict Aspen Opera Theater 2016 Echo Ariadne on Naxos Opera Theatre of Saint Louis 2016 Königin der Nacht Die Zauberflöte The Juilliard School 2016 Thérèse Les mamelles de Tirésias The Juilliard School 2015 Diane/Iphigénie* Iphigénie en Aulide Met + Juilliard 2015 Fiorilla* Il turco in Italia The Juilliard School 2014 Lakmé Lakmé Lowell House Opera 2014 Belinda Dido and Aeneas Harvard Early Music Society 2014 Tytania A Midsummer Night’s Dream Lowell House Opera 2013 La Fée Cendrillon Dunster House Opera 2013 Snegurochka* Snegurochka Lowell House Opera 2012 Susanna The Marriage of Figaro Dunster House Opera 2012 Concert Mozart: Requiem Los Angeles Master Chorale 2018 Burwell: Suite from Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri LA Philharmonic 2018 Vivaldi: Gloria Seattle Symphony 2018 Bach: Magnificat Musica Angelica 2017 Haydn: The Creation Harvard University Choir 2017 At Home New York Festival of Song 2016 Babbitt: Philomel Focus! Festival