Resuming Excavations at Chanhu-Daro, Sindh: First Results of the 2015-2017 Field-Seasons Aurore Didier, David Sarmiento Castillo, Pascal Mongne, Syed Shakir Ali Shah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PESA-DP-Hyderabad-Sindh.Pdf

Rani Bagh, Hyderabad “Disaster risk reduction has been a part of USAID’s work for decades. ……..we strive to do so in ways that better assess the threat of hazards, reduce losses, and ultimately protect and save more people during the next disaster.” Kasey Channell, Acting Director of the Disaster Response and Mitigation Division of USAID’s Office of U.S. Foreign Disas ter Ass istance (OFDA) PAKISTAN EMERGENCY SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS District Hyderabad August 2014 “Disasters can be seen as often as predictable events, requiring forward planning which is integrated in to broader de velopment programs.” Helen Clark, UNDP Administrator, Bureau of Crisis Preven on and Recovery. Annual Report 2011 Disclaimer iMMAP Pakistan is pleased to publish this district profile. The purpose of this profile is to promote public awareness, welfare, and safety while providing community and other related stakeholders, access to vital information for enhancing their disaster mitigation and response efforts. While iMMAP team has tried its best to provide proper source of information and ensure consistency in analyses within the given time limits; iMMAP shall not be held responsible for any inaccuracies that may be encountered. In any situation where the Official Public Records differs from the information provided in this district profile, the Official Public Records should take as precedence. iMMAP disclaims any responsibility and makes no representations or warranties as to the quality, accuracy, content, or completeness of any information contained in this report. Final assessment of accuracy and reliability of information is the responsibility of the user. iMMAP shall not be liable for damages of any nature whatsoever resulting from the use or misuse of information contained in this report. -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Sialkot District Reference Map September, 2014

74°0'0"E G SIALKOT DISTRICT REFBHEIMRBEER NCE MAP SEPTEMBER, 2014 Legend !> GF !> !> Health Facility Education Facility !>G !> ARZO TRUST BHU CHITTI HOSPITAL & SHEIKHAN !> MEDICAL STORE !> Sialkot City !> G Basic Health Unit !> High School !> !> !> G !> MURAD PUR BASHIR A CHAUDHARY AL-SHEIKH HOSPITAL JINNAH MEMORIAL !> MEMORIAL HOSPITAL "' CHRISTIAN HOSPITAL ÷Ó Children Hospital !> Higher Secondary IQBAL !> !> HOSPITAL !>G G DISPENSARY HOSPITAL CHILDREN !> a !> G BHAGWAL DHQ c D AL-KHIDMAT HOSPITAL OA !> SIALKOT R Dispensary AWAN BETHANIA !>CHILDREN !>a T GF !> Primary School GF cca ÷Ó!> !> A WOMEN M!>EDICAaL COMPLEX HOSPITAL HOSPITAL !> ÷Ó JW c ÷Ó !> '" A !B B D AL-SHIFA HOSPITAL !> '" E ÷Ó !> F a !> '" !B R E QURESHI HOScPITAL !> ALI HUSSAIN DHQ O N !> University A C BUKH!>ARI H M D E !>!>!> GENERAL E !> !> A A ZOHRA DISPENSARY AG!>HA ASAR HOSPITAL D R R W A !B GF L AL-KHAIR !> !> HEALTH O O A '" Rural Health Center N MEMORIAL !> HOSPITAL A N " !B R " ú !B a CENTER !> D úK Bridge 0 HOSPITAL HOSPITAL c Z !> 0 ' A S ú ' D F úú 0 AL-KHAIR aA 0 !> !>E R UR ROA 4 cR P D 4 F O W SAID ° GENERAL R E A L- ° GUJORNAT !> AD L !> NDA 2 !> GO 2 A!>!>C IQBAL BEGUM FREE DISPENSARY G '" '" Sub-Health Center 3 HOSPITAL D E !> INDIAN 3 a !> !>!> úú BHU Police Station AAMNA MEDICAL CENTER D MUGHAL HOSPIT!>AL PASRUR RD HAIDER !> !>!> c !> !>E !> !> GONDAL G F Z G !>R E PARK SIALKOT !> AF BHU O N !> AR A C GF W SIDDIQUE D E R A TB UGGOKI BHU OA L d ALI VETERINARY CLINIC D CHARITABLE BHU GF OCCUPIED !X Railway Station LODHREY !> ALI G !> G AWAN Z D MALAGAR -

Bharati Volume 4

SARASVATI Bharati Volume 4 Gold bead; Early Dynastic necklace from the Royal Cemetery; now in the Leeds collection y #/me raed?sI %/-e A/hm! #N/m! Atu?vm! , iv/Èaim?Sy r]it/ e/dm! -ar?t jn?m! . (Vis'va_mitra Ga_thina) RV 3.053.12 I have made Indra glorified by these two, heaven and earth, and this prayer of Vis'va_mitra protects the race of Bharata. [Made Indra glorified: indram atus.t.avam-- the verb is the third preterite of the casual, I have caused to be praised; it may mean: I praise Indra, abiding between heaven and earth, i.e. in va_kdevi Sarasvati the firmament]. Dr. S. Kalyanaraman Babasaheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti Bangalore 2003 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com SARASVATI: Bharati by S. Kalyanaraman Copyright Dr. S. Kalyanaraman Publisher: Baba Saheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti, Bangalore Price: (India) Rs. 500 ; (Other countries) US $50 . Copies can be obtained from: S. Kalyanaraman, 3 Temple Avenue, Srinagar Colony, Chennai, Tamilnadu 600015, India email: [email protected] Tel. + 91 44 22350557; Fax 24996380 Baba Saheb (Umakanta Keshav) Apte Smarak Samiti, Yadava Smriti, 55 First Main Road, Seshadripuram, Bangalore 560020, India Tel. + 91 80 6655238 Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti, Annapurna, 528 C Saniwar Peth, Pune 411030 Tel. +91 020 4490939 Library of Congress cataloguing in publication data Kalyanaraman, Srinivasan. Sarasvati/ S. Kalyanaraman Includes bibliographical references and index 1.River Sarasvati. 2. Indian Civilization. 3. R.gveda Printed in India at K. Joshi and Co., 1745/2 Sadashivpeth, Near Bikardas Maruti Temple, Pune 411030, Bharat ISBN 81-901126-4-0 FIRST PUBLISHED: 2003 2 PDF Created with deskPDF PDF Writer - Trial :: http://www.docudesk.com About the Author Dr. -

3-Art-Of-Indus-Valley.Pdf

Harappan civilization 2 Architecture 2 Drainage System 3 The planning of the residential houses were also meticulous. 4 Town Planning 4 Urban Culture 4 Occupation 5 Export import product of 5 Clothing 5 Important centres 6 Religious beliefs 6 Script 7 Authority and governance 7 Technology 8 Architecture Of Indus Valley Civilisation 9 The GAP 9 ARTS OF THE INDUS VALLEY 11 Stone Statues 12 MALE TORSO 12 Bust of a bearded priest 13 Male Dancer 14 Bronze Casting 14 DANCING GIRL 15 BULL 16 Terracotta 16 MOTHER GODDESS 17 Seals 18 Pashupati Seal 19 Copper tablets 19 Bull Seal 20 Pottery 21 PAINTED EARTHEN JAR 22 Beads and Ornaments 22 Toy Animal with moveable head 24 Page !1 of !26 Harappan civilization India has a continuous history covering a very long period. Evidence of neolithic habitation dating as far back as 7000 BC has been found in Mehrgarh in Baluchistan. However, the first notable civilization flourished in India around 2700 BC in the north western part of the Indian subcontinent, covering a large area. The civilization is referred to as the Harappan civilization. Most of the sites of this civilization developed on the banks of Indus, Ghaggar and its tributaries. Architecture The excavations at Harappa and Mohenjodaro and several other sites of the Indus Valley Civilisation revealed the existence of a very modern urban civilisation with expert town planning and engineering skills. The very advanced drainage system along with well planned roads and houses show that a sophisticated and highly evolved culture existed in India before the coming of the Aryans. -

Sarasvati Civilization, Script and Veda Culture Continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution

Sarasvati Civilization, script and Veda culture continuum of Tin-Bronze Revolution The monograph is presented in the following sections: Introduction including Abstract Section 1. Tantra yukti deciphers Indus Script Section 2. Momentous discovery of Soma samsthā yāga on Vedic River Sarasvati Basin Section 3. Binjor seal Section 4. Bhāratīya itihāsa, Indus Script hypertexts signify metalwork wealth-creation by Nāga-s in paṭṭaḍa ‘smithy’ = phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office, keeper of all accounts, registers’ Section 5. Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan is an Indus Script hypertext to signify Superintendent of phaḍa ‘metala manufactory’ Section 6. Note on the cobra hoods of Daimabad chariot Section 7 Note on Mohenjo-daro seal m0304: phaḍā ‘metals manufactory’ Section 8. Conclusion Introduction The locus of Veda culture and Sarasvati Civilization is framed by the Himalayan ranges and the Indian Ocean. 1 The Himalayan range stretches from Hanoi, Vietnam to Teheran, Iran and defines the Ancient Maritime Tin Route of the Indian Ocean – āsetu himācalam, ‘from the Setu to Himalayaś. Over several millennia, the Great Water Tower of frozen glacial waters nurtures over 3 billion people. The rnge is still growing, is dynamic because of plate tectonics of Indian plate juttng into and pushing up the Eurasian plate. This dynamic explains river migrations and consequent desiccation of the Vedic River Sarasvati in northwestern Bhāratam. Intermediation of the maritime tin trade through the Indian Ocean and waterways of Rivers Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, Ganga, Sarasvati, Sindhu, Persian Gulf, Tigris-Euphrates, the Mediterranean is done by ancient Meluhha (mleccha) artisans and traders, the Bhāratam Janam celebrated by R̥ ṣi Viśvāmitra in R̥ gveda (RV 3.53.12). -

Unit 6 Material Characteristics

UNIT 6 MATERIAL CHARACTERISTICS Structure Objectives Introduction From Villages to Towns.and Cities Harappan Civilization : Sources Geographical Spread Important Centres 6.5.1 Harappa 6.5.2 Mohenjodaro 6.5.3 Kalibangan 6.5.4 Lothal 6.5.5 Sutkagen-Dor Material Characteristics 6.6.1 Town-Planning 6.6.2 Pottery 6.6.3 Tools and Implements- 6.6.4 Arts and Crafts 6.6.5 The Indus Script 6.6.6 Subsistence Pattern Let Us Sum Up Key Words Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises 6.0 OBJECTIVES This Unit deals with the geographical extent and the material features of the Harappan Civilization. It describes the main sites of Harappan Civilization as well as the material remains which characterised these sites. After reading this Unit you should be able to : understand that there was continuity of population and material traditions between the Early Harappan and Harappan Civilization. know about the geographical and climatic aspects of the settlement pattern of Harappan Civilization, describe the specific geographical, climatic and subsistence related characteristics of the important centres of Harappan Civilization. learn about the material features of the impoitant Harappan sites and specially the uniformities in the material features of these sites. 6.1 INTRODUCTION In this Unit we discuss the geographical spread and material characteristics of the Harappan Civilization which aroge on the foundation of pastoral and agricultuial communities and small townships. It refers to the continuity of the population and material traditions between Early Harappan and Harappan Civilization. The geographical spread of Harappan Civilization with special reference to some important centres has been highlighted. -

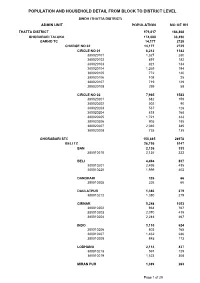

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH THATTA DISTRICT 979,817 184,868 GHORABARI TALUKA 174,088 33,450 GARHO TC 14,177 2725 CHARGE NO 02 14,177 2725 CIRCLE NO 01 6,212 1142 380020101 1,327 280 380020102 897 182 380020103 821 134 380020104 1,269 194 380020105 772 140 380020106 108 25 380020107 719 129 380020108 299 58 CIRCLE NO 02 7,965 1583 380020201 682 159 380020202 502 90 380020203 537 128 380020204 818 168 380020205 1,721 333 380020206 905 185 380020207 2,065 385 380020208 735 135 GHORABARI STC 150,885 28978 BELI TC 26,756 5147 BAN 2,136 333 380010210 2,136 333 BELI 4,494 837 380010201 2,495 435 380010220 1,999 402 DANDHARI 326 66 380010205 326 66 DAULATPUR 1,380 279 380010212 1,380 279 GIRNAR 5,248 1053 380010202 934 167 380010203 2,070 419 380010204 2,244 467 INDO 3,110 624 380010206 803 165 380010207 1,462 286 380010208 845 173 LODHANO 2,114 437 380010218 591 129 380010219 1,523 308 MIRAN PUR 1,389 263 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 380010213 529 102 380010214 860 161 SHAHPUR 3,016 548 380010215 1,300 243 380010216 901 160 380010221 815 145 SUKHPUR 1,453 275 380010209 1,453 275 TAKRO 668 136 380010217 668 136 VIKAR 1,422 296 380010211 1,422 296 GARHO TC 22,344 4350 ADANO 400 80 380010113 400 80 GAMBWAH 440 58 380010110 440 58 GUBA WEST 509 105 380010126 509 105 JARYOON 366 107 380010109 366 107 JHORE PATAR 6,123 1143 380010118 504 98 380010119 1,222 231 380010120 -

Harappan Geometry and Symmetry: a Study of Geometrical Patterns on Indus Objects

Indian Journal of History of Science, 45.3 (2010) 343-368 HARAPPAN GEOMETRY AND SYMMETRY: A STUDY OF GEOMETRICAL PATTERNS ON INDUS OBJECTS M N VAHIA AND NISHA YADAV (Received 29 October 2007; revised 25 June 2009) The geometrical patterns on various Indus objects catalogued by Joshi and Parpola (1987) and Shah and Parpola (1991) (CISI Volumes 1 and 2) are studied. These are generally found on small seals often having a boss at the back or two button-like holes at the centre. Most often these objects are rectangular or circular in shape, but objects of other shapes are also included in the present study. An overview of the various kinds of geometrical patterns seen on these objects have been given and then a detailed analysis of few patterns which stand out of the general lot in terms of the complexity involved in manufacturing them have been provided. It is suggested that some of these creations are not random scribbles but involve a certain understanding of geometry consistent with other aspects of the Indus culture itself. These objects often have preferred symmetries in their patterns. It is interesting to note that though the swastika symbol and its variants are often used on these objects, other script signs are conspicuous by their absence on the objects having geometric patterns. Key words: CISI volumes, Geometric pattern, Grid design, Swastika 1. INTRODUCTION Towns in the Indus valley have generally been recognised for their exquisite planning with orthogonal layout. This has been used to appreciate their understanding of geometry of rectangles and related shapes. -

1.2 Origin of the Indus Valley Civilization

8 MM VENKATESHWARA ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN OPEN UNIVERSITY ART AND ARCHITECTURE www.vou.ac.in ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE AND ART INDIAN ANCIENT OF ASPECTS ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE [M.A. HISTORY] VENKATESHWARA OPEN UNIVERSITYwww.vou.ac.in ASPECTS OF ANCIENT INDIAN ART AND ARCHITECTURE MA History BOARD OF STUDIES Prof Lalit Kumar Sagar Vice Chancellor Dr. S. Raman Iyer Director Directorate of Distance Education SUBJECT EXPERT Dr. Pratyusha Dasgupta Assistant Professor Dr. Meenu Sharma Assistant Professor Sameer Assistant Professor CO-ORDINATOR Mr. Tauha Khan Registrar Author: Dr. Vedbrat Tiwari, Assistant Professor, Department of History, College of Vocational Studies, University of Delhi Copyright © Author, 2019 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. Information contained in this book has been published by VIKAS® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, the Publisher and its Authors shall in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use. Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. -

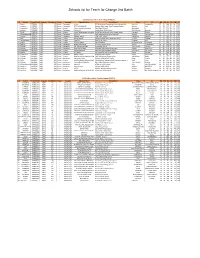

Schools List for Teach for Change 2Nd Batch

Schools list for Teach for Change 2nd Batch ESSP Schools List For Teach for Change (PHASE-II) S # District School Code Program Enrollment Phase Category Operator Name School Name Taluka UC ND NM NS ED EM ES 1 Sukkur ESSP0041 ESSP 435 Phase I Elementary Ali Bux REHMAN Model Computrized School Mubrak Pur. Pano Akil Mubarak Pur 27 40 288 69 19 729 2 Jamshoro ESSP0046 ESSP 363 Phase I Elementary RAZA MUHAMMAD Shaheed Rajib Anmol Free Education System Sehwan Arazi 26 28 132 67 47 667 3 Hyderabad ESSP0053 ESSP 450 Phase I Primary Free Journalist Foundation Zakia Model School Qasimabad 4 25 25 730 68 20 212 4 Khairpur ESSP0089 ESSP 476 Phase I Elementary Zulfiqar Ali Sachal Model Public School Thari Mirwah Kharirah 27 01 926 68 31 711 5 Ghotki ESSP0108 ESSP 491 Phase I Primary Lanjari Development foundation Sachal Sarmast model school dargahi arbani Khangarh Behtoor 27 49 553 69 20 705 6 ShaheedbenazirabaESSP0156 ESSP 201 Phase I Elementary Amir Bux Saath welfare public school (mashaik) Sakrand Gohram Mari 26 15 244 68 08 968 7 Khairpur ESSP0181 ESSP 294 Phase I Elementary Naseem Begum Faiza Public School Sobhodero Meerakh 27 15 283 68 20 911 8 Dadu ESSP0207 ESSP 338 Phase I Primary ghulam sarwar Danish Paradise New Elementary School Kn Shah Chandan 27 03 006 67 34 229 9 TandoAllahyar ESSP0306 ESSP 274 Phase I Primary Himat Ali New Vision School Chumber Jarki 25 24 009 68 49 275 10 Karachi ESSP0336 ESSP 303 Phase I Primary Kishwar Jabeen Mazin Academy Bin Qasim Twon Chowkandi 24 51 388 67 14 679 11 Sanghar ESSP0442 ESSP 589 Phase I Elementary