Redalyc. Getting out from Under the Elephant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Dobell Anglo

Policy Matters Peter Dobell What Could Ca n a d i a n s Expect from a Minority Go v e r n m e n t ? Nov. 2000 Vol. 1, no. 6 Enjeux publics ISSN 1492-7004 Policy Matters Biographical notes Peter Dobell is Founding Director of the Parliamentary Centre, which he launched in 1968 after serving for 16 years in the Canadian foreign service. The Centre aims to strengthen legislatures in Canada and around the world. 2 Enjeux publics Novembre 2000 Vol. 1, no. 6 What Could Canadians Expect from a Minority Government? Introduction 4 Past Experience 4 Changes in Procedure and Practice 10 Prospects 16 November 2000 Vol. 1, no. 6 Policy Matters 3 Peter Dobell Introduction In the last 26 years Canada has had six majority parliaments at the federal level while experiencing only one eight-month period of minority government. By contrast, during the previous 17 years — from June 1957 to July 1974 — there were five minority parliaments, interspersed by just two majority governments. Indeed between 1962 and 1968, there was a string of three successive minority governments. Even though five political parties have contested the two federal elections since 1993, a situation which makes the achievement of a majority a challenge, the Liberal party has twice during this period succeeded in winning majorities, assisted on the political right by vote splitting between the Pro g re s s i v e Conservatives and the Reform party, and on the left by the decline in support for the NDP. In 1997, however, the margin of victory for the Liberal government was slight. -

John G. Diefenbaker: the Political Apprenticeship Of

JOHN G. DIEFENBAKER: THE POLITICAL APPRENTICESHIP OF A SASKATCHEWAN POLITICIAN, 1925-1940 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon by Methodius R. Diakow March, 1995 @Copyright Methodius R. Diakow, 1995. All rights reserved. In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department for the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or pUblication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of History University of Saskatchewan 9 Campus Drive Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N 5A5 ii ABSTRACT John G. Diefenbaker is most often described by historians and biographers as a successful and popular politician. -

Download (PDF)

N° 3/2019 recherches & documents March 2019 Disarmament diplomacy Motivations and objectives of the main actors in nuclear disarmament EMMANUELLE MAITRE, research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-490100-19-4 EAN : 9782490100194 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1 – A CONVERGENCE OF PACIFIST AND HUMANITARIAN TRADITIONS ....................................... 8 1.1 – Neutrality, non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament .......................... 8 1.1.1 – Disarmament in the neutralist tradition .............................................................. 8 1.1.2 – Nuclear disarmament in a pacifist perspective .................................................. 9 1.1.1 – "Good international citizen" ..............................................................................11 1.2 – An emphasis on humanitarian issues ...............................................................13 1.2.1 – An example of policy in favor of humanitarian law ............................................13 1.2.2 – Moral, ethics and religion .................................................................................14 -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE STORY BEHIND THE STORIES British and Dominion War Correspondents in the Western Theatres of the Second World War Brian P. D. Hannon Ph.D. Dissertation The University of Edinburgh School of History, Classics and Archaeology March 2015 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 6 The Media Environment ……………...……………….……………………….. 28 What Made a Correspondent? ……………...……………………………..……. 42 Supporting the Correspondent …………………………………….………........ 83 The Correspondent and Censorship …………………………………….…….. 121 Correspondent Techniques and Tools ………………………..………….......... 172 Correspondent Travel, Peril and Plunder ………………………………..……. 202 The Correspondents’ Stories ……………………………….………………..... 241 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………. 273 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………...... 281 Appendix …………………………………………...………………………… 300 3 ABSTRACT British and Dominion armed forces operations during the Second World War were followed closely by a journalistic army of correspondents employed by various media outlets including news agencies, newspapers and, for the first time on a large scale in a war, radio broadcasters. -

Terms of Office

Terms of Office The Right Honourable Sir John Alexander Macdonald, 1 July 1867 - 5 November 1873, 17 October 1878 - 6 June 1891 The Right Honourable The Honourable Sir John A. Macdonald Alexander Mackenzie (1815-1891) (1822-1892) The Honourable Alexander Mackenzie, 7 November 1873 - 8 October 1878 The Honourable Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott, 16 June 1891 - 24 November 1892 The Right Honourable The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir John Joseph Sir John Sparrow Sir John Sparrow David Thompson, Caldwell Abbott David Thompson 5 December 1892 - 12 December 1894 (1821-1893) (1845-1894) The Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell, 21 December 1894 - 27 April 1896 The Right Honourable Sir Charles Tupper, 1 May 1896 - 8 July 1896 The Honourable The Right Honourable Sir Mackenzie Bowell Sir Charles Tupper The Right Honourable (1823-1917) (1821-1915) Sir Wilfrid Laurier, 11 July 1896 - 6 October 1911 The Right Honourable Sir Robert Laird Borden, 10 October 1911 - 10 July 1920 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen, Sir Wilfrid Laurier Sir Robert Laird Borden (1841-1919) (1854-1937) 10 July 1920 - 29 December 1921, 29 June 1926 - 25 September 1926 The Right Honourable William Lyon Mackenzie King, 29 December 1921 - 28 June 1926, 25 September 1926 - 7 August 1930, 23 October 1935 - 15 November 1948 The Right Honourable The Right Honourable The Right Honourable Arthur Meighen William Lyon Richard Bedford Bennett, (1874-1960) Mackenzie King (later Viscount), (1874-1950) 7 August 1930 - 23 October 1935 The Right Honourable Louis Stephen St. Laurent, 15 November 1948 - 21 June 1957 The Right Honourable John George Diefenbaker, The Right Honourable The Right Honourable 21 June 1957 - 22 April 1963 Richard Bedford Bennett Louis Stephen St. -

Brief by Professor François Larocque Research Chair In

BRIEF BY PROFESSOR FRANÇOIS LAROCQUE RESEARCH CHAIR IN LANGUAGE RIGHTS UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA PRESENTED TO THE SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON OFFICIAL LANGUAGES AS PART OF ITS STUDY OF THE OFFICIAL LANGUAGES REFORM PROPOSAL UNVEILED ON FEBRUARY 19, 2021, BY THE MINISTER OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND OFFICIAL LANGUAGES, ENGLISH AND FRENCH: TOWARDS A SUBSTANTIVE EQUALITY OF OFFICIAL LANGUAGES IN CANADA MAY 31, 2021 Professor François Larocque Faculty of Law, Common Law Section University of Ottawa 57 Louis Pasteur Ottawa, ON K1J 6N5 Telephone: 613-562-5800, ext. 3283 Email: [email protected] 1. Thank you very much to the honourable members of the Senate Standing Committee on Official Languages (the “Committee”) for inviting me to testify and submit a brief as part of the study of the official languages reform proposal entitled French and English: Towards a Substantive Equality of Official Languages in Canada (“the reform proposal”). A) The reform proposal includes ambitious and essential measures 2. First, I would like to congratulate the Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages for her leadership and vision. It is, in my opinion, the most ambitious official languages reform proposal since the enactment of the Constitution Act, 1982 (“CA1982”)1 and the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (“Charter”),2 which enshrined the main provisions of the Official Languages Act (“OLA”)3 of 1969 in the Canadian Constitution. The last reform of the OLA was in 1988 and it is past time to modernize it to adapt it to Canada’s linguistic realities and challenges in the 21st century. 3. The Charter and the OLA proclaim that “English and French are the official languages of Canada and have equality of status and equal rights and privileges as to their use in all institutions of the Parliament and government of Canada.”4 In reality, however, as reported by Statistics Canada,5 English is dominant everywhere, while French is declining, including in Quebec. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2017 Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War Sweazey, Connor Sweazey, C. (2017). Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25173 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/3759 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Broadcasting Canada's War: How the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Reported the Second World War by Connor Sweazey A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA APRIL, 2017 © Connor Sweazey 2017 Abstract Public Canadian radio was at the height of its influence during the Second World War. Reacting to the medium’s growing significance, members of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) accepted that they had a wartime responsibility to maintain civilian morale. The CBC thus unequivocally supported the national cause throughout all levels of its organization. Its senior administrations and programmers directed the CBC’s efforts to aid the Canadian war effort. -

Sir John A. Macdonald Vindicated, a Review of the Right Honourable

~D()4 81 \ .JOH.J. -v . • -\. ){.c\( -: .A.I.D VINDICATED A RRVIR\V OF The Right Honourable Sir Richard Cartwright's Reminiscences BY SIR JOSEPH POPF':.K.C.M.G. PRICE 250. THF. PUBLISHERS' ASSOCIATION OT" CANADA, LIMITED TORONTO ( RT. HO",. SlH HI CHAIW CART lVlU GH T REMINISCENCES By THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR RICHARD CARTWRIGHT, G.C.M.G., P.C. THIS book is not aptly named. By Reminiscences of a publi c man, is commonly understood a chat ty narration of past events - a recital of what happened during a stated period, and of th e narrator's share th erein. T he volume under considerat ion is rather an Apologia,-a justification of Sir Richard Cart wright's public career, accompanied by a denunciation of all who presumed to differ from him . Mu ch of it suggests the decrees of a Pontiff defining t hings to be believed und er pain of censure , and t his im pression is heightened by t he catechetical form in which the credenda are proclaim ed. This style, however, t hough at times irritating, is not without its compensations. It is always refreshing to find a man who is not afraid to give clear- cut expression of his views upon men and things, and t he pleasur e is enhanced when, as in t he present case, t hese views are presented in t he te rse and vigorous Saxon which Sir Richard knew so well how to employ. There"never is any doubt as to his meaning- no small advantage in th is age of quali fications and refinements. -

R=Nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- R.104TA (-{, 001

3Kcnen~lHrn 3 . ~ ,_ CCCP r=nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- r.104TA (-{, 001 diasporiana.org.ua CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON CANADIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS Unive~ty Partnership Centre I Georgian College, Barrie, ON Vol. 9 I Canada/Russia Series J.L. Black ef Andrew Donskov, general editors CRCR One-Way Ticket The Soviet Return-to-the-Homeland Campaign, 1955-1960 Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko Penumbra Press I Manotick, ON I 2008 ,l(apyHoK OmmascbKozo siooiny KaHaOCbKozo Tosapucmsa npuHmeniB YKpai°HU Copyright © 2008 Library and Archives Canada SERGE CIPKO & GLENNA ROBERTS Cataloguing-in-Publication Data No part of this publication may be Roberts, Glenna, 1934- reproduced, stored in a retrieval system Cipko, Serge, 1961- or transmitted, in any1'0rm or by any means, without the prior written One-way ticket: the Soviet return-to consent of the publisher or a licence the-homeland campaign, 1955-1960 I from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko. Agency (Access Copyright). (Canada/Russia series ; no. 9) PENUMBRA PRESS, publishers Co-published by Centre for Research Box 940 I Manotick, ON I Canada on Canadian-Russian Relations, K4M lAB I penumbrapress.ca Carleton University. Printed and bound by Custom Printers, Includes bibliographical references Renfrew, ON, Canada. and index. PENUMBRA PRESS gratefully acknowledges ISBN 978-1-897323-12-0 the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing L Canadians-Soviet Union Industry Development Program (BPIDP) History-2oth century. for our publishing activities. We also 2. Repatriation-Soviet Union acknowledge the Government of Ontario History-2oth century. through the Ontario Media Development 3. Canadians-Soviet Union Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative. -

CONSTITUTION-MAKING AS INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS a Case Study of the 1980 Canadian Constitutional Negotiations Adam D

CONSTITUTION-MAKING AS INTERGOVERNMENTAL RELATIONS A Case Study of the 1980 Canadian Constitutional Negotiations Adam D. McDonald1, University of Waterloo The Constitution Act, 1982 is a document that profoundly changed the Canadian political landscape. It brought home the highest law of the land; it provided Canadians a mechanism to change their Constitution; it created a Charter of Rights and Freedoms, entrenched within the Constitution, out of the reach of one government. Perhaps its most important legacies, however, are the seemingly permanent isolation of Quebec and the primacy of place in Canadian history it gave Pierre Trudeau. This paper will examine the constitutional history of Canada with a view to determining what made the 1980 negotiating sessions successful when the sessions that led to both the Meech Lake Accord and the Charlottetown Accord were not. It is important, however, to note that the word “successful” is used in the sense that an agreement was reached. Unlike Meech and Charlottetown, the repatriated constitution did not have unanimity among the participants. The question that comes to mind is this: if the governments did not really agree in 1981, why was a Constitution ratified? More importantly, are there lessons that can be drawn from this agreement that can be applied to the failed accords of the Mulroney era? In order to complete this examination, the paper will be divided into two parts. In the first part, Canada’s constitutional story will be told. This is a necessary part of any examination of the constitutional negotiations, for without knowing what the players wanted historically, one cannot see what was changed by the 1980s. -

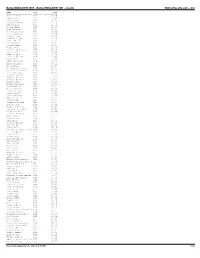

Bolderboulder 2005 - Bolderboulder 10K - Results Onlineraceresults.Com

BolderBOULDER 2005 - BolderBOULDER 10K - results OnlineRaceResults.com NAME DIV TIME ---------------------- ------- ----------- Michael Aish M28 30:29 Jesus Solis M21 30:45 Nelson Laux M26 30:58 Kristian Agnew M32 31:10 Art Seimers M32 31:51 Joshua Glaab M22 31:56 Paul DiGrappa M24 32:14 Aaron Carrizales M27 32:23 Greg Augspurger M27 32:26 Colby Wissel M20 32:36 Luke Garringer M22 32:39 John McGuire M18 32:42 Kris Gemmell M27 32:44 Jason Robbie M28 32:47 Jordan Jones M23 32:51 Carl David Kinney M23 32:51 Scott Goff M28 32:55 Adam Bergquist M26 32:59 trent r morrell M35 33:02 Peter Vail M30 33:06 JOHN HONERKAMP M29 33:10 Bucky Schafer M23 33:12 Jason Hill M26 33:15 Avi Bershof Kramer M23 33:17 Seth James DeMoor M19 33:20 Tate Behning M23 33:22 Brandon Jessop M26 33:23 Gregory Winter M26 33:25 Chester G Kurtz M30 33:27 Aaron Clark M18 33:28 Kevin Gallagher M25 33:30 Dan Ferguson M23 33:34 James Johnson M36 33:38 Drew Tonniges M21 33:41 Peter Remien M25 33:45 Lance Denning M43 33:48 Matt Hill M24 33:51 Jason Holt M18 33:54 David Liebowitz M28 33:57 John Peeters M26 34:01 Humberto Zelaya M30 34:05 Craig A. Greenslit M35 34:08 Galen Burrell M25 34:09 Darren De Reuck M40 34:11 Grant Scott M22 34:12 Mike Callor M26 34:14 Ryan Price M27 34:15 Cameron Widoff M35 34:16 John Tribbia M23 34:18 Rob Gilbert M39 34:19 Matthew Douglas Kascak M24 34:21 J.D.