FULL REPORT Data Collected in August/September 2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CULTURES DE RENTE ET REDUCTION DES RISQUES DE CATASTROPHE, Cas Du District D’Antalaha

Université d’Antananarivo Faculté de Droit d’Economie de Gestion et de Sociologie Département Economie - Troisième Cycle Diplôme d’études supérieures spécialisées Multidisciplinaire en Gestion des Risques et des Catastrophes DMGRC Mémoire de fin d’études pour l’obtention du Diplôme d’études supérieures spécialisées Multidisciplinaire en Gestion des Risques et des Catastrophes CULTURES DE RENTE ET REDUCTION DES RISQUES DE CATASTROPHE, Cas du district d’Antalaha Présenté par : RAZAKANDRAINY Mandimby Encadreur pédagogique : Mr ANDRIANANJA Heriniaina Rakotovao. Date de soutenance : 30 Août 2011 Université d’Antananarivo Faculté de Droit d’Economie de Gestion et de Sociologie Département Economie - Troisième Cycle Diplôme d’études supérieures spécialisées Multidisciplinaire en Gestion des Risques et des Catastrophes DMGRC Mémoire de fin d’études pour l’obtention du Diplôme d’études supérieures spécialisées Multidisciplinaire en Gestion des Risques et des Catastrophes CULTURES DE RENTE ET REDUCTION DES RISQUES DE CATASTROPHE, Cas du district d’Antalaha Présenté par : RAZAKANDRAINY Mandimby Encadreur pédagogique : Mr ANDRIANANJA Heriniaina Rakotovao. Août 2011 REMERCIEMENTS Avant tout, nous rendons grâce à DIEU tout puissant, de nous avoir accordé la force, l’intelligence et la bonne santé durant les années de formation et la période de stage. Nous exprimons ici nos sincères remerciements à : - Monsieur RANDRIANALIJAONA Tiana Mahefasoa, Directeur de la formation DMGRC, d’avoir sacrifié son temps et ses efforts pour le bien de notre formation -

Université D Faculté Des Lettres Départemen

UNIVERSITÉ D’ANTANANARIVO FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉOGRAPHIE Filière Spécialisée en Environnement et Aménagement du Territoire (F.S.E.A.T) MÉMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE MAITRISE « VULNERABILITE DE LA VILLE COTIERE FACE AUX CYCLONES : CAS DE LA COMMUNE URBAINE D’ANTALAHA REGION SAVA » Présenté par : BE MELSON Evrald Angelo Sous la direction de : Madame Simone RATSIVALAKA, Professeur Titulaire au Département de Géographie Date de soutenance : 1O Octobre 2014 Octobre 2014 UNIVERSITÉ D’ANTANANARIVO FACULTÉ DES LETTRES ET SCIENCES HUMAINES DÉPARTEMENT DE GÉOGRAPHIE Filière Spécialisée en Environnement et Aménagement du Territoire (F.S.E.A.T) MÉMOIRE POUR L’OBTENTION DU DIPLÔME DE MAITRISE « VULNERABILITE DE LA VILLE COTIERE FACE AUX CYCLONES : CAS DE LA COMMUNE URBAINE D’ANTALAHA REGION SAVA » Présenté par : BE MELSON Evrald Angelo Président du jury : James RAVALISON, Professeur Rapporteur : Simone RATSIVALAKA, Professeur Titulaire Juge : Mparany ANDRIAMIHAMINA, Maitre de conférences Octobre 2014 REMERCIEMENTS Ce mémoire de Maitrise n’aurait pas été ce qu’il est aujourd’hui, sans le concours de plusieurs personnes, à qui nous aimerons témoigner notre plus profonde reconnaissance. Tout d’abord, nous remercions de tout profond de notre cœur le Dieu Tout Puissant de nous avoir donné encore la vie et l’opportunité d’avoir pu mener à terme ce travail de recherche. Aussi, Monsieur James RAVALISON, Professeur pour avoir accepté de présider notre soutenance ; Monsieur Mparany ANDRIAMIHAMINA, Maître de conférences pour avoir accepté de juger notre soutenance ; Madame Simone RATSIVALAKA, notre Directeur de mémoire pour sa constante dévotion à notre travail malgré ses multiples occupations. -

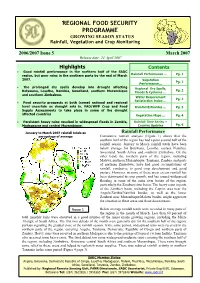

GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring

REGIONAL FOOD SECURITY PROGRAMME GROWING SEASON STATUS Rainfall, Vegetation and Crop Monitoring 2006/2007 Issue 5 March 2007 Release date: 24 April 2007 Highlights Contents • Good rainfall performance in the northern half of the SADC region, but poor rains in the southern parts by the end of March Rainfall Performance … Pg. 1 2007. Vegetation Pg. 2 Performance… • The prolonged dry spells develop into drought affecting Regional Dry Spells, Pg. 2 Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Swaziland, southern Mozambique Floods & Cyclones … and southern Zimbabwe. Water Requirement Pg. 2 Satisfaction Index … • Food security prospects at both (some) national and regional level uncertain as drought sets in. FAO/WFP Crop and Food Rainfall Estimates … Pg. 3 Supply Assessments to take place in some of the drought affected countries Vegetation Maps … Pg. 4 • Persistent heavy rains resulted in widespread floods in Zambia, Rainfall Time Series + Madagascar and central Mozambique. Country Updates Pg. 6 January to March 2007 rainfall totals as Rainfall Performance percentage of average Cumulative rainfall analysis (Figure 1) shows that the southern half of the region has had a poor second half of the rainfall season. January to March rainfall totals have been below average for Botswana, Lesotho, eastern Namibia, Swaziland, South Africa and southern Zimbabwe. On the other hand, the northern parts of the region, including Malawi, northern Mozambique, Tanzania, Zambia, and parts of northern Zimbabwe, have had good accumulations of rainfall, conducive to good crop development and good pasture. However, in some of these areas excess rainfall has been detrimental to crop growth, and has caused widespread flooding in some of the main river basins of the region, particularly the Zambezi river basin. -

WTO Documents Online

WORLD TRADE G/AG/N/EU/2 16 February 2012 ORGANIZATION (12-0913) Committee on Agriculture Original: English NOTIFICATION The following submission, dated 16 November 2011, is being circulated at the request of the Delegation of the European Union. The notification concerns actions taken within the framework of the Decision on Measures Concerning the Possible Negative Effects of the Reform Programme on Least-Developed and Net Food-Importing Developing Countries (Table NF:1) during the calendar year 2007. G/AG/N/EU/2 Page 2 NOTIFICATION UNDER ARTICLE 16:2 OF THE AGREEMENT: MONITORING OF THE FOLLOW-UP TO THE DECISION ON MEASURES CONCERNING THE POSSIBLE EFFECTS OF THE REFORM PROGRAMME ON LEAST-DEVELOPED AND NET FOOD-IMPORTING DEVELOPING COUNTRIES: European Union REPORTING PERIOD: calendar year 2007 (1) Quantity of food aid provided to least-developed and net food-importing developing countries: 1. The contribution by the European Union (EU) for food aid and support operations in 2007 was €308 million. It was spent on products mobilized under the Food Aid Convention (FAC) and on contract aid provided by European Commission Directorate General for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (DG ECHO). The contract aid was spent on products, support operations and transport, distribution, flanking measures and measures to monitor implementation. A substantial contribution to food aid and supporting operations was also delivered by Directorate General for Development and Relations with African, Caribbean and Pacific Countries (DG DEV) as part of Official Development Assistance delivered by the European Commission. 2. As a result of reorganization of instruments under the EU's Financial Perspectives exercise for 2007-2013, the responsibility for the management of humanitarian food aid budget line was transferred from the European Commission Directorate General EuropeAid Cooperation Office (DG AIDCO) to DG ECHO with effect from January 2007. -

Floods in the Northern Part of the Country and Drought in the South Resulted in Nearly 500,000 People in Need of Assistance

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HUMANITARIAN / RESIDENT COORDINATOR ON THE USE OF CERF GRANTS Country Madagascar Humanitarian / Resident Coordinator Mr. Xavier Leus Reporting Period 1 January 2007- 12 August 2007 I. Executive Summary On the 20 February 2007, the Malagasy Government declared a national state of emergency in Madagascar after a succession of particularly severe storms – including Bondo, Clovis, Favio and Gamede – had battered the island since December. By the end of March, the combined effects of extensive floods in the northern part of the country and drought in the south resulted in nearly 500,000 people in need of assistance. Against this backdrop, a new cyclone, Indlala, struck the north-eastern coast of Madagascar on 15th March, with winds of more than 230 km/h. Even after moving inland, it still registered gusts up to 125 km/h. The storm also continued to unleash torrential rains. Floods washed away villages in the northeast of the country, silted paddy fields and other large agricultural areas, damaged road infrastructure, washed away bridges and made it impossible to reach a number of remote villages where communities remained in dire need of immediate relief aid. These conditions contributed to extensive flooding in heavily populated and cultivated areas throughout the country, including the capital region, the northwest, the northeast, and the southeast. The food security situation deteriorated dramatically, and the risk of maternal and child mortality linked to lack of access to services, and water- and vector-borne diseases, increased. The situation threatened to deteriorate further were timely assistance not provided to address immediate needs and restore agricultural production and livelihoods before the next cyclone season. -

Cyclone Relief- AFMG71 Appeal Target: US$ 599, 047

150 route de Ferney, P.O. Box 2100 1211 Geneva 2, Switzerland Tel: 41 22 791 6033 Fax: 41 22 791 6506 Appeal E-mail: [email protected] Madagascar Coordinating Office Cyclone relief- AFMG71 Appeal Target: US$ 599, 047 Geneva, 30 April 2007 Dear Colleagues, Cyclone Indlala hit the north-eastern coast of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar on 15 March 2007. With strong winds of up to 200 kilometres/hour (km/h), the cyclone ravaged the immediate area in its path (mainly Maroantsetra) and left considerable damage on the Northeast and Northwest regions. Cyclone Indlala was the fifth cyclone to have hit Madagascar within the past months: Cyclone Bondo made landfall on 25 December 2006; Cyclone Clovis on 3 January 2007; Cyclone Favio on 18 January 2007; and Cyclone Gamede on 26 February 2007. On 3 April 2007, a sixth cyclone (Cyclone Jaya), hit the country, causing further damage and displacement; its wind speed was 150 km/h at the highest peak while Indlala's was 235 km/h. Cyclone Jaya did not make significant impact compared to Indlala because vulnerable groups had lost all their belongings during successive cyclone passages and their related floods. This is the first time that Madagascar has been struck by so many cyclones in such a short period. Seasonal rains have been made worse by the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) moving slightly south, resulting in continuous rains - from the end of December 2006 to the present moment - and resultant flooding. ACT member Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar (FJKM) is appealing for support to enable them to provide immediate needs including targeted food distribution, non-food items (NFI), basic recovery items and the rehabilitation of schools damaged by the cyclones. -

Revised Emergency Appeal No

MADAGASCAR: Emergency Appeal no. MDRMG002 CYCLONES 12 April 2007 This Emergency Appeal revises the Preliminary Emergency Appeal launched on 22 March, 2007. The Federation’s mission is to improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity. It is the world’s largest humanitarian organization and its millions of volunteers are active in over 185 countries. In Brief THIS EMERGENCY APPEAL SEEKS CHF 2,005,707 (USD 1,649,430 OR EUR 1,238,090) IN CASH, KIND OR SERVICES TO ASSIST 60,000 BENEFICIARIES (12,000 HOUSEHOLDS) FOR 6 MONTHS. <Click here to link directly to the attached Appeal budget and here to go directly to the attached map> Appeal history: A DREF Bulletin on Cyclone Clovis was issued on 19 January 2007. A second DREF Bulletin on cyclone preparedness was issued on 16 March 2007. A Preliminary Emergency Appeal on Cyclone Indlala was launched on 22 March 2007. This operation is aligned with the International Federation's Global Agenda, which sets out four broad goals to meet the Federation's mission to "improve the lives of vulnerable people by mobilizing the power of humanity". Global Agenda Goals: · Reduce the numbers of deaths, injuries and impact from disasters. · Reduce the number of deaths, illnesses and impact from diseases and public health emergencies. · Increase local community, civil society and Red Cross Red Crescent capacity to address the most urgent situations of vulnerability. · Reduce intolerance, discrimination and social exclusion and promote respect for diversity and human dignity. The situation Cyclone Indlala hit the north-eastern coast of the Indian Ocean island of Madagascar on Thursday, 15 March 2007. -

Madagascar: Cyclone Ivan

Final Report Madagascar: Emergency Appeal n°MDRMG003 Cyclone Ivan 4 May 2009 Period covered by this Final Report: 6 March to 6 September 2008; Appeal target (current): CHF 1,074,882 (USD 937,938 or EUR 712,324) Final Appeal coverage: 68% Click here to go directly to the interim final financial report or here to view the contact details> Appeal history: · The Emergency appeal was launched on 6 March 2008 for CHF1, 074,880 (USD 961,431 Red Cross volunteers preparing for NFI distribution or EUR 651,442) for 6 months to assist 10,000 families. · Operations update no.1, issued on 15 May 2008, focused on assessments and distributions conducted by the Malagasy Red Cross Society (MRCS), the DM Federation representative and other stakeholders. · Initially a total of CHF 108,719 was allocated from the International Federation’s Disaster Relief Emergency Funds (DREF). Summary: The frequency of cyclones affecting Madagascar and the extent of damage caused in recent years, have enabled the Malagasy Red Cross Society to increase its capacity to respond. Volunteers were trained in carrying out assessments, distributions and follow up evaluations. Procurement of containers and use in pre-positioning stocks in seven different locations, improved the National Society’s rapid response capacity for the 2008 to 2009 season. As in previous years the time required to complete local procurement procedures was underestimated resulting in some distributions and pre-positioning of stocks being behind schedule. Hygiene kits were also distributed to the beneficiaries; however this activity was constrained due to untimely distribution in some areas. This operation was conducted in collaboration with the Malagasy Government and United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). -

Champon Vanilla, Inc. 4521 PGA Blvd

Champon Vanilla Specializing in Vanilla Beans • Vanilla Products • Flavor & Fragrance Ingredients Madagascar hit by another devastating cyclone dpa German Press Agency Published: Friday March 16, 2007 Antananarivo- Rain- and wind-battered Madagascar off the east coast of Africa was on Friday experiencing its fourth heavy cyclone in recent months. Cyclone Indlala that hit land in the tropical island on Thursday, continued to rage over its vanilla plantations on Friday. The cities of Sambava, Antalaha and Maroantsetra in the north, flooding large areas and leaving inhabitants without telephone links. Antalaha, the centre of vanilla production, already hard-hit by earlier devastating cyclones, has lost an estimated 90 per cent of its crops. The cyclone, that featured strong winds, also caused damage to police buildings and the those of the aid agency, Care International in Antalaha. Germany on Friday made available 22,000 euros for victims of the extreme weather amid appeals from aid agencies for international assistance for tens of thousands of islanders affected by cyclones. In Maroantsetra heavy winds ripped away part if the roof of a prison and damaged the power supply late Thursday. Ten prisoners saw an opportunity and fled into the night, but three were rearrested. Three cyclones in recent weeks have left approximately 45,000 people displaced, an estimated 18,000 in the capital Antananarivo. At least seven people have been reported killed as a result of the weather. The Malagasy government declared a state of emergency and asked the international community for assistance for the impoverished country that has already lost most of its rice harvest and flooded around 85,000 hectares of cultivated land. -

Emergency Humanitarian Aid for Populations Affected by Cyclone Indlala

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR HUMANITARIAN AID - ECHO Emergency Humanitarian Aid Decision 23 02 01 Title: Emergency humanitarian aid for populations affected by cyclone Indlala Location of operation: Madagascar Amount of Decision: EUR 1,500,000 Decision reference number: ECHO/MDG/BUD/2007/02000 Explanatory Memorandum 1 - Rationale, needs and target population. 1.1. - Rationale: Intense tropical cyclone Indlala touched land on the 15 March South of Antalaha town (73,000 inhabitants) and has pursued its way to the South-West, impacting the town of Maroantsetra (20,000 inhabitants) before crossing several regions in Madagascar with its wind strength eventually fading. It has led to destructions due to high winds and to severe floods following the heavy rains in several parts of Northern Madagascar (Diana and Sofia districts in the North-West and Sava, Analanjirofo in the North-East of the island, with Ambanja, Mampikony, Antsohyhi districts, amongst others). As of 30 March at least 80 people have been killed and tens of thousands have been made homeless or lost their belongings. Large areas of agricultural land have been flooded and crops destroyed1. The cyclone Indlala struck at a time when Madagascar was already dealing with the consequences of several cyclones (cyclone Bondo, tropical storms Clovis, Enok, Favio and cyclone Gamede) which, since December 2006, have caused exceptionally heavy rainfall affecting in particular communication, health and agriculture infrastructures. In addition, this year's rainy season has brought exceptional rains to most of the island.2 Considering the 1Estimations of the number of causalities after Malagasy Bureau National de Gestion des Risques et des Catastrophes (BN GRC) 2As an example, rains in Antananarivo corresponded to 150% of the average, while in Mananjary (South-East) and in the western part of the island, they reached 300% of the average. -

(SWIO-RAFI): Component 1 - Hazard

Southwest Indian Ocean Risk Assessment Financing Initiative (SWIO-RAFI): Component 1 - Hazard FINAL Report Submitted to the World Bank June 1st, 2016 SWIO RAFI Component 1 Report - FINAL Copyright 2016 AIR Worldwide Corporation. All rights reserved. Trademarks AIR Worldwide is a registered trademark in the European Union. Confidentiality AIR invests substantial resources in the development of its models, modeling methodologies and databases. This document contains proprietary and confidential information and is intended for the exclusive use of AIR clients who are subject to the restrictions of the confidentiality provisions set forth in license and other nondisclosure agreements. Contact Information If you have any questions regarding this document, contact: AIR Worldwide Corporation 388 Market Street, Suite 750 San Francisco, CA 94111 USA Tel: (415) 912-3111 Fax: (415) 912-3112 i SF15-1061 COMP1REP SWIO RAFI Component 1 Report - FINAL Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1 Limitations .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 2 Hazard Catalogs and Analysis ............................................................................................................................... -

CYCLONES and FLOODS – REVISION

CYCLONES and FLOODS – REVISION CYCLONES and FLOODS – REVISION WFP/Madagascar/2007 Consolidated Appeals Process (CAP) The CAP is much more than an appeal for money. It is an inclusive and coordinated programme cycle of: • Strategic planning leading to a Common Humanitarian Action Plan (CHAP); • Resource mobilisation (leading to a Consolidated Appeal or a Flash Appeal); • Coordinated programme implementation; • Joint monitoring and evaluation; • Revision, if necessary; and • Reporting on results. The CHAP is a strategic plan for humanitarian response in a given country or region and includes the following elements: • A common analysis of the context in which humanitarian action takes place; • An assessment of needs; • Best, worst, and most likely scenarios; • Stakeholder analysis, i.e. who does what and where; • A clear statement of longer-term objectives and goals; • Prioritised response plans; and • A framework for monitoring the strategy and revising it if necessary. The CHAP is the foundation for developing a Consolidated Appeal or, when crises break or natural disasters strike, a Flash Appeal. Under the leadership of the Humanitarian Coordinator, the CHAP is developed at the field level by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Country Team. This team mirrors the IASC structure at headquarters and includes UN agencies and standing invitees, i.e. the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, and NGOs that belong to ICVA, Interaction, or SCHR. Non-IASC members, such as national NGOs, can be included, and other key stakeholders in humanitarian action, in particular host governments and donors, should be consulted. The Humanitarian Coordinator is responsible for the annual preparation of the consolidated appeal document .