Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

A Genealogical Linguistic Implication of the Abaluhyia Naming System

IJRDO-Journal of Social Science and Humanities Research ISSN : 2456-2971 A GENEALOGICAL LINGUISTIC IMPLICATION OF THE ABALUHYIA NAMING SYSTEM David Wafula Lwangale (Egerton University) [email protected] or [email protected] ABSTRACT Most African communities have a systematic way of naming their children. The naming system of a given community speaks a lot about their way of life. Some communities have family names which cannot be attributed to any meaning. Such names may be regarded generally as clan names. Some names may be attributed to some events and seasons. Others may be inherited in a situation where communities name their children after their dead or living relatives. Therefore, names are not only cultural but also linguistic. The study investigated the naming systems of the Luhyia sub-tribes with a view of establishing the genealogical relatedness of the Luluhyia language dialects. The study established three levels of naming children shared by most of the Luhyia sub-nations. These are based on seasons, events and naming after their dead relatives. Key words: genealogical, language, name, male and female Background to the Study Luhyia dialects have been extensively studied over a long period of time. The speakers of Luluhyia dialects are generally referred to as AbaLuhyia who were initially known as Bantu Kavirondo as a result of their being close to Lake Victoria in Kavirondo Gulf. The Luhyia nation, tribe or ethnic group consists of seventeen sub-nations or dialect speaking sub-groups. These include Abakhayo, Babukusu, Abanyala, Abanyore, Abatsotso, Abetakho, Abesukha, Abakabras, Abakisa, Abalogoli, Abamarachi, Abasamia, Abatachoni, Abatiriki and Abawanga. -

A Collection of 100 Tachoni Proverbs and Wise Sayings

A COLLECTION OF 100 TACHONI PROVERBS AND WISE SAYINGS By ANNASTASI OISEBE African Proverbs Working Group NAIROBI, KENYA AUGUST, 2017. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to acknowledge and thank the relentless effort for all those who played a major part in completion of this document. My utmost thanks go to Fr. Joseph G. Healey, both financial and moral support. My special thanks goes to CephasAgbemenu, Margaret Ireri and Elias Bushiri who guided me accordingly to ensure that my research was completed. Furthermore I also want to thank Edwin Kola for his enormous assistance, without forgetting publishers of Tachoni proverbs and resources who made this research possible. DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my parents Anthony and Margret Oisebe and the entire African Proverbs working group Nairobi and all readers of African literature. INTRODUCTION Location The Tachoni (We shall be back in Kalenjin) are Kalenjins assimilated by Luhya people of Western Kenya, sharing land with the Bukusu tribe. They live mainly in Webuye, Chetambe Hills, Ndivisi (of Bungoma County) and the former Lugari District in the Kakamega County. Most Tachoni clans living in Bungoma speak the 'Lubukusu' dialect of the Luhya language making them get mistaken as Bukusus. They spread to Trans-Nzoia County especially around Kitale, Mumias and Busia. The ethnic group is rich in beliefs and taboos. The most elaborate cultural practice they have is circumcision. The ethnographical location of the Tachoni ethnic group in Kenya Myth of Origin One of the most common myths among the Luhya group relates to the origin of the Earth and human beings. According to this myth, Were (God) first created Heaven, then Earth. -

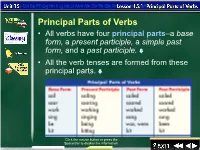

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

Culture, Minorities and Linguistic Rights in Uganda

CULTURE, MINORITIES AND LINGUISTIC RIGHTS IN UGANDA: THE C ASE O F T HE B ATWA A ND T HE Ik Kabann I.B. Kabananukye and Dorothy Kwagala Copyright Human Rights & Peace Centre, 2007 ISBN 9970-511-10-x HURIPEC Working Paper No. 11 June, 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS...........................................................ii LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES.................................................................iii SUMMARY OF THE REPORT AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS...............iv I. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND.......................................1 II. CONTEXTUALIZING THE CASE OF ETHNIC MINORITIES.............3 2.1 ENHANCING THE UNDERSTANDING OF ETHNIC MINORITIES.........................3 2.2 CONTEXTUALIZING MINORITIES’ CULTURE AND LANGUAGE........................4 2.3 THE LANGUAGE FACTOR: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES.....................5 2.3.1 Understanding the Importance of Language.......................5 2.3.2 Ethnic Minorities’ Languages.............................................8 III. MINORITIES AND UGANDA’S LINGUSITIC & ETHNIC GROUPS...9 3.1 THE CASE OF THE BATWA.................................................................11 3.1.1 Batwa distribution by Region and District.........................12 3.1.2 Comparision of the Batwa and the Bakiga.......................14 3.2 THE CASE OF THE IK...................................................................16 3.2.1 Distribution of Ik Peoples by Region in Uganda................17 3.2.2 Distribution of Ik by Districts in Uganda..........................17 -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology. -

Surrogate Surfaces: a Contextual Interpretive Approach to the Rock Art of Uganda

SURROGATE SURFACES: A CONTEXTUAL INTERPRETIVE APPROACH TO THE ROCK ART OF UGANDA by Catherine Namono The Rock Art Research Institute Department of Archaeology School of Geography, Archaeology & Environmental Studies University of the Witwatersrand A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2010 i ii Declaration I declare that this is my own unaided work. It is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before for any other degree or examination in any other university. Signed:……………………………….. Catherine Namono 5th March 2010 iii Dedication To the memory of my beloved mother, Joyce Lucy Epaku Wambwa To my beloved father and friend, Engineer Martin Wangutusi Wambwa To my twin, Phillip Mukhwana Wambwa and Dear sisters and brothers, nieces and nephews iv Acknowledgements There are so many things to be thankful for and so many people to give gratitude to that I will not forget them, but only mention a few. First and foremost, I am grateful to my mentor and supervisor, Associate Professor Benjamin Smith who has had an immense impact on my academic evolution, for guidance on previous drafts and for the insightful discussions that helped direct this study. Smith‘s previous intellectual contribution has been one of the corner stones around which this thesis was built. I extend deep gratitude to Professor David Lewis-Williams for his constant encouragement, the many discussions and comments on parts of this study. His invaluable contribution helped ideas to ferment. -

An Examination of Ethnic Stereotypes and Coded Language Used in Kenya and Its Implication for National Cohesion

International Journal of Development and Sustainability ISSN: 2186-8662 – www.isdsnet.com/ijds Volume 7 Number 11 (2018): Pages 2670-2693 ISDS Article ID: IJDS18052103 An examination of ethnic stereotypes and coded language used in Kenya and its implication for national cohesion Joseph Gitile Naituli 1*, Sellah Nasimiyu King’oro 2 1 Multimedia University Of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya 2 National Cohesion and Integration Commission, Nairobi, Kenya Abstract Kenya is a highly multi-ethnic, multi-linguistic and multicultural country. In spite of extensive co-existence and interactions between citizens, who largely communicate using Kiswahili and English, most Kenyans are not able to understand indigenous Kenyan languages other than their own. This paper therefore, interrogates the ethnic stereotypes and coded language used by ethnic communities in Kenya and how they are perceived by the users and target communities. The study adopted qualitative survey design and it involved 1223 participants sampled from 39 counties using purposive sampling technique, spread over all the regions of Kenya. Data was generated primarily using interviews, focused group discussions and document analysis. Open ended questionnaires were used to supplement these sources, where necessary. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics by use of mean and standard deviations and trend analysis. The findings are presented in form of tables and figures. The findings show that there is use of stereotypes and coded language amongst all Kenyan communities and stereotypes and coded language bring out both positive and negative perceptions about the communities referred to. The implications for this study are that, there is an urgent need to educate Kenyans on the unique features of different Kenyan communities. -

“Possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31

Nomen: ____________________________________________________________________________ Classis: ________ Review Notes: “possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31 Principal parts of the verb “possum”: possum, posse, potui, ----- to be able to, can Possum is a compound of the verb sum. It is essentially the prefix pot added to the irregular verb sum. However, the letter t in the prefix pot becomes s in front of all forms of sum beginning with the letter s. Let’s look at the forms of the verb “possum” below and their translations: Present Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1. possum I can, I am able possumus We can, we are able 2. potes You can, you are able potestis Y’all can, are able 3. potest He/she/it can, is able possunt They can, are able Imperfect Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.poteram I could, was able poteramus We could, were able 2.poteras You could, were able poteratis Y’all could, were able 3.poterat He/she/it could, was able poterant They could, were able Future Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.potero I will be able poterimus We will be able 2.poteris You will be able poteritis Y’all will be able 3.poterit He/she/it will be able poterunt They will be able So what about the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect forms of the verb “possum”? These tenses are regular, meaning possum follows the normal rules. Let’s look at them. Start by rewriting your principal parts of the verb: Possum, posse, potui, ------ to be able to, can Just like all other verbs, switch to the 3rd principal part when you want to work in the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

Songs and Dances Among the Abagusii of Kenya : a Historical Study Evans Omosa Nyamwaka

Songs and dances among the Abagusii of Kenya : a historical study Evans Omosa Nyamwaka To cite this version: Evans Omosa Nyamwaka. Songs and dances among the Abagusii of Kenya : a historical study. History. 2000. dumas-01332864 HAL Id: dumas-01332864 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-01332864 Submitted on 16 Jun 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SONGS AND DANCES AMONG THE ABAGUSII OF KENYA: A HISTORICAL STUDY SERA EMU in vl FRA0011008 0 7 / 0,31 o,5 BY Y A . 76. NYAMWAKA EVANS OMOSA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS OF EGERTON UNIVERSITY August,2000 11 DECLARATION AND APPROVAL This Thesis is my Original Work and has not been presented for award of a degree to any other University. Signature fvJ Date RO\ g ZDOC) NYAMWAKA, EVANS OMOSA This Thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as the Candidate's Supervisor. Signature Date LJ— PROF. MWANIKI H.S.K. iii DEDICATION DEDICATED TO MY DEAR FATHER, SAMUEL NYAMWAKA OINGA, MY DEAR MOTHER, SIBIA KWAMBOKA NYAMWAKA AND MY BROTHER, GIDEON OYAGI iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, I wish to thank our heavenly Father for having created me and exposing me to the world of intricacies whereby I have encountered several experiences which have shaped me to what I am today.