23. 25. 2011. X 14. 12. 2012, Â

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Klinci Neki Novi

SJAJNI MOMCI: LAZAR RISTOVSKI: Savršeni glumački trio! „Ljubav i praštanje izumiru!“ P.b.b. Verlagspostamt 1020 GZ 09Z037990M GZ 09Z037990M Verlagspostamt 1020 P.b.b. KO04/2017 | IZDANJE BR. 82 | NAŠSMO NAJTIRAŽNIJI MAGAZIN U AUSTRIJI | WWW.KOSMO.AT neki novi klinciEKSKLUZIVNO SUROVA REALNOST: Oni nemaju ni 18 godina, a već nose oružje, plja čkaju, ko nzumiraju i diluju drogu. Für unbeschwerte und sichere Urlaubstage. reiseregistrierung.at Damit wir Sie auch im Ernstfall erreichen können. Gratis App-Download zur Reiseregistrierung Informationen zu Ihrem Urlaubsziel finden Sie unter: www.reiseinformation.at Ein Service des Außenministeriums Bitte beachten Sie: Die Reiseregistrierung ersetzt nicht die Eigenverantwortung! Bei Notfällen im Ausland sind wir jederzeit unter +43-1-90115-4411 für Sie erreichbar. STARS REPORTAŽASPORT 22 U ulozi detektiva 46 Intervju: Miomir Mike Bjelić je profesionalni detektiv Lazar Ristovski koji nam otkriva sve opasnosti ovog posla. On ima iza sebe preko 4.000 predstava, 73 uloga, a već i dva romana. Za KOSMO govori ovaj svestrani umetnik i veliki glumac. COVER 30 Neki novi klinci Mnogi od njih su još uvek maloletnici, ali već nose oružje, plja čkaju, ko nzumiraju i diluju drogu. Naš reporter je uspeo da razgovara sa jednom mladom bandom kriminalaca. 14 POLITIKA 38 ZDRAVLJE 60 AUTOMOTO 64 SPORT Prijem. Predsedavajući Veća Vakcinacija. Manjina va Generacija na dva točka. Živa legenda. Gde je ministara BiH, Denis Zvizdić, kcinisanih u Austriji dovela je Segway već pokazuje da je danas Vanja Grbić? Naša bio je u dvodnevnoj zvaničnoj do zaraze boginjama. Preti li vozilo budućnosti. Saznajte sve dopisnička redakcija je srela poseti Republici Austriji. -

Candidatura Duta Laurentiu (PDF)

FORMULAR DE CERERE CANDIDATURA PENTRU ALEGEREA Iil FUNCTIA DE MEMBRU AL CONSILIULUI DIRECTOR AL UCMR-ADA PENTRU ADUNAREA GENERALA ORDII{ARA DIN 15II7.06.2021 SubematuYa: Domit$lirt(i) in: (Stad4 Nr., Bloc, Et, Apanamed) Conbd: Btrcl CT{P: doresc s5 imi depun candidatura pentru alegerea ca membru al consiliului Director al uCMR-ADA ordi-nara"'.'u,ir.' ce urmeaza -[ff:,h:ffijjffi1:X,n*"da ucr',rR-ADA din drt di5/1;ffi02, penru Categoria statuta zcr;zr, oinr. .l,r.'ti ffff1,*:i$::::,y:.:rjlJ,i*. i,lii,".l,te de art 7 2 5 oin st i,t,iir6urn-eoe, arL 7 .2.5lit. a), respectiu arl.7.2.5 U), r*O* din partea ',,uniunii profesionala in oomentu (creatiei mulcale) art. 7.2.5 lit. c), tl resp@ n Declar ca am oiecttimeA 5 ani in calitate de nembnt aIOCMR_ADE \clar ne popriiEsptffi re, l!!:yrtiy,it:pn@prevdzute e de art. 4.2.3 din Stitutut UCUn-iOn." j Anexez prezentei: ; ,). : I a) CV; < :*$,-. fl\ , .' I b)v, copiecl;wprEl vt, prezentarea t: il ] c) obiectivelor pe care ,l le voi urmSri in cazut alegerii rnele Directorat ca membru al consiliului ' ;g5q _=.4, ' uGMR-ADA; '' l'rl,Xiff'3i:J:riffi'Jffiilproresionara'pentucatesoriireprevazuteraart 725a'n(1) I!;"- ',8" ] i ; -- sunt de acord ca cV-ul gi obiectivele candidaturii mele si fie ficute publice pe g6MR-ADA. n.. t :' de acord .u pr.rrcirr.a webste-ul lunt ori.iJ#il;;#".r personar poriv* i+fui prevederiror GDRp. * 1- .l' DataudLd . Nuggle sj,prenumele in clal $i semnatur n J-t "a q,'J-^d -, -i".",,bre.,*::.;:,::j,":j""*,","IPJ:;:'W":3:;ff^zArl d 2 3 lncomparlrrrx p,rro - ..i,irJ"r"i", alc"eluju' -

L'italia E L'eurovision Song Contest Un Rinnovato

La musica unisce l'Europa… e non solo C'è chi la definisce "La Champions League" della musica e in fondo non sbaglia. L'Eurovision è una grande festa, ma soprattutto è un concorso in cui i Paesi d'Europa si sfidano a colpi di note. Tecnicamente, è un concorso fra televisioni, visto che ad organizzarlo è l'EBU (European Broadcasting Union), l'ente che riunisce le tv pubbliche d'Europa e del bacino del Mediterraneo. Noi italiani l'abbiamo a lungo chiamato Eurofestival, i francesi sciovinisti lo chiamano Concours Eurovision de la Chanson, l'abbreviazione per tutti è Eurovision. Oggi più che mai una rassegna globale, che vede protagonisti nel 2016 43 paesi: 42 aderenti all'ente organizzatore più l'Australia, che dell'EBU è solo membro associato, essendo fuori dall'area (l’anno scorso fu invitata dall’EBU per festeggiare i 60 anni del concorso per via dei grandi ascolti che la rassegna fa in quel paese e che quest’anno è stata nuovamente invitata dall’organizzazione). L'ideatore della rassegna fu un italiano: Sergio Pugliese, nel 1956 direttore della RAI, che ispirandosi a Sanremo volle creare una rassegna musicale europea. La propose a Marcel Bezençon, il franco-svizzero allora direttore generale del neonato consorzio eurovisione, che mise il sigillo sull'idea: ecco così nascere un concorso di musica con lo scopo nobile di promuovere la collaborazione e l'amicizia tra i popoli europei, la ricostituzione di un continente dilaniato dalla guerra attraverso lo spettacolo e la tv. E oltre a questo, molto più prosaicamente, anche sperimentare una diretta in simultanea in più Paesi e promuovere il mezzo televisivo nel vecchio continente. -

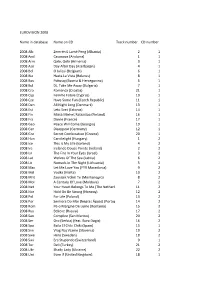

EUROVISION 2008 Name in Database Name on CD Track Number CD

EUROVISION 2008 Name in database Name on CD Track number CD number 2008 Alb Zemrën E Lamë Peng (Albania) 2 1 2008 And Casanova (Andorra) 1 1 2008 Arm Qele, Qele (Armenia) 3 1 2008 Aze Day After Day (Azerbaijan) 4 1 2008 Bel O Julissi (Belgium) 6 1 2008 Bie Hasta La Vista (Belarus) 8 1 2008 Bos Pokusaj (Bosnia & Herzegovina) 5 1 2008 Bul DJ, Take Me Away (Bulgaria) 7 1 2008 Cro Romanca (Croatia) 21 1 2008 Cyp Femme Fatale (Cyprus) 10 1 2008 Cze Have Some Fun (Czech Republic) 11 1 2008 Den All Night Long (Denmark) 13 1 2008 Est Leto Svet (Estonia) 14 1 2008 Fin Missä Miehet Ratsastaa (Finland) 16 1 2008 Fra Divine (France) 17 1 2008 Geo Peace Will Come (Georgia) 19 1 2008 Ger Disappear (Germany) 12 1 2008 Gre Secret Combination (Greece) 20 1 2008 Hun Candlelight (Hungary) 1 2 2008 Ice This Is My Life (Iceland) 4 2 2008 Ire Irelande Douze Pointe (Ireland) 2 2 2008 Isr The Fire In Your Eyes (Israel) 3 2 2008 Lat Wolves Of The Sea (Latvia) 6 2 2008 Lit Nomads In The Night (Lithuania) 5 2 2008 Mac Let Me Love You (FYR Macedonia) 9 2 2008 Mal Vodka (Malta) 10 2 2008 Mnt Zauvijek Volim Te (Montenegro) 8 2 2008 Mol A Century Of Love (Moldova) 7 2 2008 Net Your Heart Belongs To Me (The Netherlands) 11 2 2008 Nor Hold On Be Strong (Norway) 12 2 2008 Pol For Life (Poland) 13 2 2008 Por Senhora Do Mar (Negras Águas) (Portugal) 14 2 2008 Rom Pe-o Margine De Lume (Romania) 15 2 2008 Rus Believe (Russia) 17 2 2008 San Complice (San Marino) 20 2 2008 Ser Oro (Serbia) (feat. -

Gender and Geopolitics in the Eurovision Song Contest Introduction

Gender and Geopolitics in the Eurovision Song Contest Introduction Catherine Baker Lecturer, University of Hull [email protected] http://www.suedosteuropa.uni-graz.at/cse/en/baker Contemporary Southeastern Europe, 2015, 2(1), 74-93 Contemporary Southeastern Europe is an online, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary journal that publishes original, scholarly, and policy-oriented research on issues relevant to societies in Southeastern Europe. For more information, please contact us at [email protected] or visit our website at www.contemporarysee.org Introduction: Gender and Geopolitics in the Eurovision Song Contest Catherine Baker* Introduction From the vantage point of the early 1990s, when the end of the Cold War not only inspired the discourses of many Eurovision performances but created opportunities for the map of Eurovision participation itself to significantly expand in a short space of time, neither the scale of the contemporary Eurovision Song Contest (ESC) nor the extent to which a field of “Eurovision research” has developed in cultural studies and its related disciplines would have been recognisable. In 1993, when former Warsaw Pact states began to participate in Eurovision for the first time and Yugoslav successor states started to compete in their own right, the contest remained a one-night-per- year theatrical presentation staged in venues that accommodated, at most, a couple of thousand spectators and with points awarded by expert juries from each participating country. Between 1998 and 2004, Eurovision’s organisers, the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), and the national broadcasters responsible for hosting each edition of the contest expanded it into an ever grander spectacle: hosted in arenas before live audiences of 10,000 or more, with (from 2004) a semi-final system enabling every eligible country and broadcaster to participate each year, and with (between 1998 and 2008) points awarded almost entirely on the basis of telephone voting by audiences in each participating state. -

MA Thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics

MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 1 The Stylistics of Language Switches in Lyrics of Entries of the Eurovision Song Contest MA thesis: Linguistics: English Language and Linguistics Sean de Goede S0871346 First reader: Tony Foster Second reader: Lettie Dorst Leiden University Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics 08-06-2015 Language Switches in Eurovision Song Contest Lyrics 2 Acknowledgements It did not come as a surprise to the people around me when I told them that the subject for my Master’s thesis was going to be based on the Eurovision Song Contest. Ever since I was a little boy I have been a fan, and some might even say that I became somewhat obsessed, for which I cannot really blame them. Moreover, I have always had a special interest in mixed language songs, so linking the two subjects seemed only natural. Thanks to a rather unfortunate turn of events, this thesis took a lot longer to write than was initially planned, but nevertheless, here it is. Special thanks are in order for my supervisor, Tony Foster, who has helped me in many ways during this time. I would also like to thank a number of other people for various reasons. The second reader Lettie Dorst. My mother, for being the reason I got involved with the Eurovision Song Contest. My father, for putting up with my seemingly endless collection of Eurovision MP3s in the car. -

Eurovision Karaoke

1 Eurovision Karaoke ALBANÍA ASERBAÍDJAN ALB 06 Zjarr e ftohtë AZE 08 Day after day ALB 07 Hear My Plea AZE 09 Always ALB 10 It's All About You AZE 14 Start The Fire ALB 12 Suus AZE 15 Hour of the Wolf ALB 13 Identitet AZE 16 Miracle ALB 14 Hersi - One Night's Anger ALB 15 I’m Alive AUSTURRÍKI ALB 16 Fairytale AUT 89 Nur ein Lied ANDORRA AUT 90 Keine Mauern mehr AUT 04 Du bist AND 07 Salvem el món AUT 07 Get a life - get alive AUT 11 The Secret Is Love ARMENÍA AUT 12 Woki Mit Deim Popo AUT 13 Shine ARM 07 Anytime you need AUT 14 Conchita Wurst- Rise Like a Phoenix ARM 08 Qele Qele AUT 15 I Am Yours ARM 09 Nor Par (Jan Jan) AUT 16 Loin d’Ici ARM 10 Apricot Stone ARM 11 Boom Boom ÁSTRALÍA ARM 13 Lonely Planet AUS 15 Tonight Again ARM 14 Aram Mp3- Not Alone AUS 16 Sound of Silence ARM 15 Face the Shadow ARM 16 LoveWave 2 Eurovision Karaoke BELGÍA UKI 10 That Sounds Good To Me UKI 11 I Can BEL 86 J'aime la vie UKI 12 Love Will Set You Free BEL 87 Soldiers of love UKI 13 Believe in Me BEL 89 Door de wind UKI 14 Molly- Children of the Universe BEL 98 Dis oui UKI 15 Still in Love with You BEL 06 Je t'adore UKI 16 You’re Not Alone BEL 12 Would You? BEL 15 Rhythm Inside BÚLGARÍA BEL 16 What’s the Pressure BUL 05 Lorraine BOSNÍA OG HERSEGÓVÍNA BUL 07 Water BUL 12 Love Unlimited BOS 99 Putnici BUL 13 Samo Shampioni BOS 06 Lejla BUL 16 If Love Was a Crime BOS 07 Rijeka bez imena BOS 08 D Pokušaj DUET VERSION DANMÖRK BOS 08 S Pokušaj BOS 11 Love In Rewind DEN 97 Stemmen i mit liv BOS 12 Korake Ti Znam DEN 00 Fly on the wings of love BOS 16 Ljubav Je DEN 06 Twist of love DEN 07 Drama queen BRETLAND DEN 10 New Tomorrow DEN 12 Should've Known Better UKI 83 I'm never giving up DEN 13 Only Teardrops UKI 96 Ooh aah.. -

Serbia Feels the Heat Over Šešelj Extradition

Issue No. 181 Friday, April 03 - Thursday, April 16, 2015 ORDER DELIVERY TO Ties of wood Traces of Nazi Tango fever YOUR DOOR +381 11 4030 303 become occupation strikes [email protected] - - - - - - - ISSN 1820-8339 1 golden linger in Belgrade BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY 0 1 opportunity Belgrad once again Page 5 Page 9 Page 10 9 7 7 1 8 2 0 8 3 3 0 0 0 Even when the Democrats longas continue to likely is This also are negotiations Drawn-out Surely the situation is urgent Many of us who have experi We feel in-the-know because bia has shown us that (a.) no single no (a.) that us shown has bia party or coalition will ever gain the governa form to required majority negotiations political (b.) and ment, will never be quickly concluded. achieved their surprising result at last month’s general election, quickly itbecame clear that the re sult was actually more-or-less the result election other every as same in Serbia, i.e. inconclusive. as Serbia’s politicians form new political parties every time disagree with they their current party reg 342 currently are (there leader political parties in Serbia). istered the norm. One Ambassador Belgrade-based recently told me he was also alarmed by the distinct lack of urgency among politicians. Serbian “The country is standstill at and a I don’t understand their logic. If they are so eager to progress towards the EU and en theycome how investors, courage go home at 5pm sharp and don’t work weekends?” overtime. -

Vilt Liaugodien KITO PROBLEMA JEAN-PAUL SARTRE'o Ir SIMONE

VYTAUTO DIDŽIOJO UNIVERSITETAS HUMANITARINI Ų MOKSL Ų FAKULTETAS FILOSOFIJOS KATEDRA Vilt ė Liaugodien ė KITO PROBLEMA JEAN-PAUL SARTRE‘O ir SIMONE de BEAUVOIR FILOSOFIJOSE Magistro baigiamasis darbas Praktin ės filosofijos studij ų programa, valstybinis kodas 62101H103 Filosofijos studij ų kryptis Vadovas doc. dr. Dalius Jonkus ______________ ___________ (parašas) (data) Apginta _________________ ______________ ____________ (Fakulteto dekanas) (parašas) (data) Kaunas, 2009 TURINYS Santrauka....................................................................................................................................3 ĮVADAS.....................................................................................................................................5 1. Kito problema Sartre‘o filosofijoje........................................................................................9 1.1. Gėda ir žvilgsnis...........................................................................................................9 1.2. K ūnai ir fenomenai.....................................................................................................11 1.3. Laisv ė ir konkurencija ................................................................................................12 1.4 Neigimas.....................................................................................................................15 2. Simone de Beauvoir ..............................................................................................................17 2.1. Simone -

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc

Name Artist Composer Album Grouping Genre Size Time Disc Number Disc Count Track Number Track Count Year Date Mod ified Date Added Bit Rate Sample Rate Volume Adjustment Kind Equalizer Comments Plays Last Played Skips Last Ski pped My Rating Because The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 4149082 165 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# DF7AFDAC Carry That Weight The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 2501496 96 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 74 DF4189 Come Together The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 6431772 260 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 5081C2D4 The End The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 3532174 139 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 909B4CD9 Golden Slumbers The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 2374226 91 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# D91DAA47 Her Majesty The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 731642 23 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 8427BD1F 1 02.07.2011 13:33 Here Comes The Sun The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 4629955 185 1969 02.07.2011 13:37 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 23 6DC926 3 30.10.2011 18:20 4 02.07.2011 13:34 I Want You The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 11388347 467 1969 02.07.2011 13:38 02.07.20 11 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 97501696 Maxwell's Silver Hammer The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 5150946 207 1969 02.07.2011 13:38 02.07.2011 13:31 192 44100 MPEG audio file , AG# 78 0B3499 Mean Mr Mustard The Beatles Abbey Road Pop 1767349 66 1969 -

University of Groningen Inequality and Solidarity Fink, Simon; Klein, Lars

University of Groningen Inequality and Solidarity Fink, Simon; Klein, Lars; de Jong, Janny; Waal, van der, Margriet IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2020 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Fink, S., Klein, L., de Jong, J., & Waal, van der, M. (Eds.) (2020). Inequality and Solidarity: Selected Texts Presented at the Euroculture Intensive Programme 2019 . (2020 ed.) Euroculture consortium. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors -

Elena - Before I Sleep Frank Knebel Edit Zippy ->->->->

Elena - Before I Sleep Frank Knebel Edit Zippy ->->->-> http://shorl.com/dabyrijelifry 1 / 3 . Before I Sleep (Frank Knebel Radio Remix) 15 Ianuarie 2009: 4120: . Loredana ft. Connect-R - Regina (Radio Edit) 13 Ianuarie 2009: 3090: . Elena Gheorghe .Who is Gary A Knebel - (319) 377-1763 - Marion - IA - waatp.com.See also Gary A Knebel: pictures, social networks profiles, videos, weblinks, at blogs, at news, books .Elena - Before I Sleep (Frank Knebel Remix) tema del ao 2007. 3:27 Play Stop Download. Elena Gheorghe - Midnight Sun (Radio Edit) cel mai nou single Elena.VA- Vocal Trance - Digitally Imported Premium [2012, Vocal Trance, . Before You Leave Me .12 Before I Sleep (Frank Knebel Edit) - Elena. 13 The Other Side - Paul Van Dyk featuring Wayne Jackson. 14 I Go Crazy (Giuseppe D.'s Radio Edit) .Elena Hasna - Colaj de melodii. Elena - Before I Sleep (Frank Knebel Edit) Elena Gheorghe - Disco Romancing; Elena Gheorghe - Te ador; Elena Gheorghe - The Balkan .VA-Vocal Trance - Digitally Imported Premium [2012, . VA-Vocal Trance - Digitally Imported Premium .Trance VA-Vocal Trance - Digitally Imported Premium . Digitally Imported Premium / [2012, Vocal . Elena - Before I Sleep (Frank .. (joebermudezandklubjumbersradioedit)www.file24ever.com.mp3: . 09-aboveandbeyond- cantsleepwww . 12-elena-beforeisleep(frankknebeledit)www .Watch the video, get the download or listen to elena Before I Sleep (Frank Knebel Edit) for free. Discover more music, gig and concert tickets, videos, lyrics .Welcome to listen to the song "The Best Of Female Vocal Trance Vol 01 11". If this song is the copyright belongs to you, .Browse 84 lyrics and 136 Elena albums. Lyrics. Before I Sleep (Frank Knebel remix) 41: Before I Sleep (original edit) 42: Disco Romancing .Disco Romancing (Radio Edit) Disco Romancing (Video Edit) Disco Romancing .