A Theory of Atmospheric Oxygen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline of Natural History

Timeline of natural history This timeline of natural history summarizes significant geological and Life timeline Ice Ages biological events from the formation of the 0 — Primates Quater nary Flowers ←Earliest apes Earth to the arrival of modern humans. P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs Times are listed in millions of years, or Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda megaanni (Ma). -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota – z ←Earliest animals o ←Earliest plants i Multicellular -1000 — c Contents life ←Sexual reproduction Dating of the Geologic record – P r The earliest Solar System -1500 — o t Precambrian Supereon – e r Eukaryotes Hadean Eon o -2000 — z o Archean Eon i Huron ian – c Eoarchean Era ←Oxygen crisis Paleoarchean Era -2500 — ←Atmospheric oxygen Mesoarchean Era – Photosynthesis Neoarchean Era Pong ola Proterozoic Eon -3000 — A r Paleoproterozoic Era c – h Siderian Period e a Rhyacian Period -3500 — n ←Earliest oxygen Orosirian Period Single-celled – life Statherian Period -4000 — ←Earliest life Mesoproterozoic Era H Calymmian Period a water – d e Ectasian Period a ←Earliest water Stenian Period -4500 — n ←Earth (−4540) (million years ago) Clickable Neoproterozoic Era ( Tonian Period Cryogenian Period Ediacaran Period Phanerozoic Eon Paleozoic Era Cambrian Period Ordovician Period Silurian Period Devonian Period Carboniferous Period Permian Period Mesozoic Era Triassic Period Jurassic Period Cretaceous Period Cenozoic Era Paleogene Period Neogene Period Quaternary Period Etymology of period names References See also External links Dating of the Geologic record The Geologic record is the strata (layers) of rock in the planet's crust and the science of geology is much concerned with the age and origin of all rocks to determine the history and formation of Earth and to understand the forces that have acted upon it. -

Dating the Paleoproterozoic Snowball Earth Glaciations Using Contemporaneous Subglacial Hydrothermal Systems

Dating the Paleoproterozoic snowball Earth glaciations using contemporaneous subglacial hydrothermal systems D.O. Zakharov1, I.N. Bindeman1, A.I. Slabunov2, M. Ovtcharova3, M.A. Coble4, N.S. Serebryakov5, and U. Schaltegger3 1Department of Earth Sciences, 1272 University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403, USA 2Institute of Geology, Karelian Research Centre, RAS, Pushkinskaya 11, Petrozavodsk 185910, Russia 3Department of Earth Sciences, University of Geneva, 13, Rue des Maraîchers, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland 4Geological Sciences Department, Stanford University, 367 Panama Street, Stanford, California 94305, USA 5Institute of Petrography, Mineralogy and Geology of Ore Deposits, RAS, Staromonetny per. 35, Moscow 119017, Russia ABSTRACT on the continent during the early Paleoproterozoic. As the Baltic Shield The presence of Paleoproterozoic glacial diamictites deposited was located at low latitudes (latitudes 20°–30°; Bindeman et al., 2010; at low latitudes on different continents indicates that three or four Salminen et al., 2014) when the low-δ18O hydrothermally altered rocks worldwide glaciations occurred between 2.45 and 2.22 Ga. During formed, reconstructed low δ18O (as low as −40‰) of original meteoric that time period, the first atmospheric oxygen rise, known as the water suggest low-latitude, snowball Earth glaciations, which is in line Great Oxidation Event (GOE), occurred, implying a potential con- with deposition of glacial diamictites at low latitudes (Evans et al., 1997). nection between these events. Herein we combine triple oxygen iso- Thus, by applying precise U-Pb geochronology to intrusions with low- tope systematics and in situ and high-precision U-Pb zircon ages of δ18O signatures from the Baltic Shield, we can directly date the presence mafic intrusions to date two episodes of snowball Earth glaciations. -

A Community Effort Towards an Improved Geological Time Scale

A community effort towards an improved geological time scale 1 This manuscript is a preprint of a paper that was submitted for publication in Journal 2 of the Geological Society. Please note that the manuscript is now formally accepted 3 for publication in JGS and has the doi number: 4 5 https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2020-222 6 7 The final version of this manuscript will be available via the ‘Peer reviewed Publication 8 DOI’ link on the right-hand side of this webpage. Please feel free to contact any of the 9 authors. We welcome feedback on this community effort to produce a framework for 10 future rock record-based subdivision of the pre-Cryogenian geological timescale. 11 1 A community effort towards an improved geological time scale 12 Towards a new geological time scale: A template for improved rock-based subdivision of 13 pre-Cryogenian time 14 15 Graham A. Shields1*, Robin A. Strachan2, Susannah M. Porter3, Galen P. Halverson4, Francis A. 16 Macdonald3, Kenneth A. Plumb5, Carlos J. de Alvarenga6, Dhiraj M. Banerjee7, Andrey Bekker8, 17 Wouter Bleeker9, Alexander Brasier10, Partha P. Chakraborty7, Alan S. Collins11, Kent Condie12, 18 Kaushik Das13, Evans, D.A.D.14, Richard Ernst15, Anthony E. Fallick16, Hartwig Frimmel17, Reinhardt 19 Fuck6, Paul F. Hoffman18, Balz S. Kamber19, Anton Kuznetsov20, Ross Mitchell21, Daniel G. Poiré22, 20 Simon W. Poulton23, Robert Riding24, Mukund Sharma25, Craig Storey2, Eva Stueeken26, Rosalie 21 Tostevin27, Elizabeth Turner28, Shuhai Xiao29, Shuanhong Zhang30, Ying Zhou1, Maoyan Zhu31 22 23 1Department -

Timing and Tempo of the Great Oxidation Event

Timing and tempo of the Great Oxidation Event Ashley P. Gumsleya,1, Kevin R. Chamberlainb,c, Wouter Bleekerd, Ulf Söderlunda,e, Michiel O. de Kockf, Emilie R. Larssona, and Andrey Bekkerg,f aDepartment of Geology, Lund University, Lund 223 62, Sweden; bDepartment of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY 82071; cFaculty of Geology and Geography, Tomsk State University, Tomsk 634050, Russia; dGeological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, ON K1A 0E8, Canada; eDepartment of Geosciences, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm 104 05, Sweden; fDepartment of Geology, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa; and gDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521 Edited by Mark H. Thiemens, University of California, San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved December 27, 2016 (received for review June 11, 2016) The first significant buildup in atmospheric oxygen, the Great situ secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS) on microbaddeleyite Oxidation Event (GOE), began in the early Paleoproterozoic in grains coupled with precise isotope dilution thermal ionization association with global glaciations and continued until the end of mass spectrometry (ID-TIMS) and paleomagnetic studies, we re- the Lomagundi carbon isotope excursion ca. 2,060 Ma. The exact solve these uncertainties by obtaining accurate and precise ages timing of and relationships among these events are debated for the volcanic Ongeluk Formation and related intrusions in because of poor age constraints and contradictory stratigraphic South Africa. These ages lead to a more coherent global per- correlations. Here, we show that the first Paleoproterozoic global spective on the timing and tempo of the GOE and associated glaciation and the onset of the GOE occurred between ca. -

Globally Asynchronous Sulphur Isotope Signals Require Re-Definition of the Great Oxidation Event

Globally asynchronous sulphur isotope signals require re-definition of the Great Oxidation Event. Pascal Philippot, Janaína N. Ávila, Bryan A. Killingsworth, Svetlana Tessalina, Franck Baton, Tom Caquineau, Élodie Muller, Ernesto Pecoits, Pierre Cartigny, Stefan V. Lalonde, et al. To cite this version: Pascal Philippot, Janaína N. Ávila, Bryan A. Killingsworth, Svetlana Tessalina, Franck Baton, et al.. Globally asynchronous sulphur isotope signals require re-definition of the Great Oxidation Event.. Nature Communications, Nature Publishing Group, 2018, 9 (1), pp.2245. 10.1038/s41467-018-04621- x. hal-01822553 HAL Id: hal-01822553 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01822553 Submitted on 2 Jul 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial| 4.0 International License ARTICLE DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-04621-x OPEN Globally asynchronous sulphur isotope signals require re-definition of the Great Oxidation Event Pascal Philippot1,2, Janaína N. Ávila 3, Bryan A. Killingsworth 4, Svetlana Tessalina 5, Franck Baton1, Tom Caquineau1, Elodie Muller1, Ernesto Pecoits1,8, Pierre Cartigny1, Stefan V. Lalonde 4, Trevor R. Ireland 3, Christophe Thomazo 6, Martin J. van Kranendonk7 & Vincent Busigny 1 The Great Oxidation Event (GOE) has been defined as the time interval when sufficient 1234567890():,; atmospheric oxygen accumulated to prevent the generation and preservation of mass-independent fractionation of sulphur isotopes (MIF-S) in sedimentary rocks. -

A Template for an Improved Rock-Based Subdivision of the Pre-Cryogenian Timescale

Downloaded from http://jgs.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Perspective Journal of the Geological Society Published Online First https://doi.org/10.1144/jgs2020-222 A template for an improved rock-based subdivision of the pre-Cryogenian timescale Graham A. Shields1*, Robin A. Strachan2, Susannah M. Porter3, Galen P. Halverson4, Francis A. Macdonald3, Kenneth A. Plumb5, Carlos J. de Alvarenga6, Dhiraj M. Banerjee7, Andrey Bekker8, Wouter Bleeker9, Alexander Brasier10, Partha P. Chakraborty7, Alan S. Collins11, Kent Condie12, Kaushik Das13, David A. D. Evans14, Richard Ernst15,16, Anthony E. Fallick17, Hartwig Frimmel18, Reinhardt Fuck6, Paul F. Hoffman19,20, Balz S. Kamber21, Anton B. Kuznetsov22, Ross N. Mitchell23, Daniel G. Poiré24, Simon W. Poulton25, Robert Riding26, Mukund Sharma27, Craig Storey2, Eva Stueeken28, Rosalie Tostevin29, Elizabeth Turner30, Shuhai Xiao31, Shuanhong Zhang32, Ying Zhou1 and Maoyan Zhu33 1 Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, London, UK 2 School of the Environment, Geography and Geosciences, University of Portsmouth, Portsmouth, UK 3 Department of Earth Science, University of California at Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara, CA, USA 4 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, Canada 5 Geoscience Australia (retired), Canberra, Australia 6 Instituto de Geociências, Universidade de Brasília, Brasilia, Brazil 7 Department of Geology, University of Delhi, Delhi, India 8 Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Riverside, -

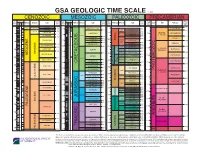

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

PHANEROZOIC and PRECAMBRIAN CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHY 2016

PHANEROZOIC and PRECAMBRIAN CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHY 2016 Series/ Age Series/ Age Erathem/ System/ Age Epoch Stage/Age Ma Epoch Stage/Age Ma Era Period Ma GSSP/ GSSA GSSP GSSP Eonothem Eon Eonothem Erathem Period Eonothem Period Eon Era System System Eon Erathem Era 237.0 541 Anthropocene * Ladinian Ediacaran Middle 241.5 Neo- 635 Upper Anisian Cryogenian 4.2 ka 246.8 proterozoic 720 Holocene Middle Olenekian Tonian 8.2 ka Triassic Lower 249.8 1000 Lower Mesozoic Induan Stenian 11.8 ka 251.9 Meso- 1200 Upper Changhsingian Ectasian 126 ka Lopingian 254.2 proterozoic 1400 “Ionian” Wuchiapingian Calymmian Quaternary Pleisto- 773 ka 259.8 1600 cene Calabrian Capitanian Statherian 1.80 Guada- 265.1 Proterozoic 1800 Gelasian Wordian Paleo- Orosirian 2.58 lupian 268.8 2050 Piacenzian Roadian proterozoic Rhyacian Pliocene 3.60 272.3 2300 Zanclean Kungurian Siderian 5.33 Permian 282.0 2500 Messinian Artinskian Neo- 7.25 Cisuralian 290.1 Tortonian Sakmarian archean 11.63 295.0 2800 Serravallian Asselian Meso- Miocene 13.82 298.9 r e c a m b i n P Neogene Langhian Gzhelian archean 15.97 Upper 303.4 3200 Burdigalian Kasimovian Paleo- C e n o z i c 20.44 306.7 Archean archean Aquitanian Penn- Middle Moscovian 23.03 sylvanian 314.6 3600 Chattian Lower Bashkirian Oligocene 28.1 323.2 Eoarchean Rupelian Upper Serpukhovian 33.9 330.9 4000 Priabonian Middle Visean 38.0 Carboniferous 346.7 Hadean (informal) Missis- Bartonian sippian Lower Tournaisian Eocene 41.0 358.9 ~4560 Lutetian Famennian 47.8 Upper 372.2 Ypresian Frasnian Units of the international Paleogene 56.0 382.7 Thanetian Givetian chronostratigraphic scale with 59.2 Middle 387.7 Paleocene Selandian Eifelian estimated numerical ages. -

Paleogeographic Maps Earth History

History of the Earth Age AGE Eon Era Period Period Epoch Stage Paleogeographic Maps Earth History (Ma) Era (Ma) Holocene Neogene Quaternary* Pleistocene Calabrian/Gelasian Piacenzian 2.6 Cenozoic Pliocene Zanclean Paleogene Messinian 5.3 L Tortonian 100 Cretaceous Serravallian Miocene M Langhian E Burdigalian Jurassic Neogene Aquitanian 200 23 L Chattian Triassic Oligocene E Rupelian Permian 34 Early Neogene 300 L Priabonian Bartonian Carboniferous Cenozoic M Eocene Lutetian 400 Phanerozoic Devonian E Ypresian Silurian Paleogene L Thanetian 56 PaleozoicOrdovician Mesozoic Paleocene M Selandian 500 E Danian Cambrian 66 Maastrichtian Ediacaran 600 Campanian Late Santonian 700 Coniacian Turonian Cenomanian Late Cretaceous 100 800 Cryogenian Albian 900 Neoproterozoic Tonian Cretaceous Aptian Early 1000 Barremian Hauterivian Valanginian 1100 Stenian Berriasian 146 Tithonian Early Cretaceous 1200 Late Kimmeridgian Oxfordian 161 Callovian Mesozoic 1300 Ectasian Bathonian Middle Bajocian Aalenian 176 1400 Toarcian Jurassic Mesoproterozoic Early Pliensbachian 1500 Sinemurian Hettangian Calymmian 200 Rhaetian 1600 Proterozoic Norian Late 1700 Statherian Carnian 228 1800 Ladinian Late Triassic Triassic Middle Anisian 1900 245 Olenekian Orosirian Early Induan Changhsingian 251 2000 Lopingian Wuchiapingian 260 Capitanian Guadalupian Wordian/Roadian 2100 271 Kungurian Paleoproterozoic Rhyacian Artinskian 2200 Permian Cisuralian Sakmarian Middle Permian 2300 Asselian 299 Late Gzhelian Kasimovian 2400 Siderian Middle Moscovian Penn- sylvanian Early Bashkirian -

2009 Geologic Time Scale Cenozoic Mesozoic Paleozoic Precambrian Magnetic Magnetic Bdy

2009 GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST. HIST. ANOM. ANOM. (Ma) CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 65.5 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 542 CALABRIAN MAASTRICHTIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE 1.8 31 C31 251 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 70.6 254 2A PIACENZIAN 32 C32 L 630 C2A 3.6 WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN 33 CAMPANIAN CAPITANIAN 5 C3 5.3 266 750 NEOPRO- CRYOGENIAN 80 C33 M WORDIAN MESSINIAN LATE 268 TEROZOIC 3A C3A 83.5 ROADIAN 7.2 SANTONIAN 271 85.8 KUNGURIAN 850 4 276 C4 CONIACIAN 280 4A 89.3 ARTINSKIAN TONIAN C4A L TORTONIAN 90 284 TURONIAN PERMIAN 10 5 93.5 E 1000 1000 C5 SAKMARIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 297 99.6 ASSELIAN STENIAN SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 299.0 5A 100 300 GZELIAN C5A 13.8 M KASIMOVIAN 304 1200 PENNSYL- 306 1250 15 5B LANGHIAN ALBIAN MOSCOVIAN MESOPRO- C5B VANIAN 312 ECTASIAN 5C 16.0 110 BASHKIRIAN TEROZOIC C5C 112 5D C5D MIOCENE 320 318 1400 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 326 6 C6 APTIAN 20 120 1500 CALYMMIAN E 20.4 6A C6A EARLY MISSIS- M0r 125 VISEAN 1600 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 SIPPIAN M3 BARREMIAN C6C 23.0 345 6C CRETACEOUS 130 M5 130 STATHERIAN CARBONIFEROUS TOURNAISIAN 7 C7 HAUTERIVIAN 1750 25 7A M10 C7A 136 359 8 C8 L CHATTIAN M12 VALANGINIAN 360 L 1800 140 M14 140 9 C9 M16 FAMENNIAN BERRIASIAN M18 PROTEROZOIC OROSIRIAN 10 C10 28.4 145.5 M20 2000 30 11 C11 TITHONIAN 374 PALEOPRO- 150 M22 2050 12 E RUPELIAN -

Alphabetical List

LIST E - GEOLOGIC AGE (STRATIGRAPHIC) TERMS - ALPHABETICAL LIST Age Unit Broader Term Age Unit Broader Term Aalenian Middle Jurassic Brunhes Chron upper Quaternary Acadian Cambrian Bull Lake Glaciation upper Quaternary Acheulian Paleolithic Bunter Lower Triassic Adelaidean Proterozoic Burdigalian lower Miocene Aeronian Llandovery Calabrian lower Pleistocene Aftonian lower Pleistocene Callovian Middle Jurassic Akchagylian upper Pliocene Calymmian Mesoproterozoic Albian Lower Cretaceous Cambrian Paleozoic Aldanian Lower Cambrian Campanian Upper Cretaceous Alexandrian Lower Silurian Capitanian Guadalupian Algonkian Proterozoic Caradocian Upper Ordovician Allerod upper Weichselian Carboniferous Paleozoic Altonian lower Miocene Carixian Lower Jurassic Ancylus Lake lower Holocene Carnian Upper Triassic Anglian Quaternary Carpentarian Paleoproterozoic Anisian Middle Triassic Castlecliffian Pleistocene Aphebian Paleoproterozoic Cayugan Upper Silurian Aptian Lower Cretaceous Cenomanian Upper Cretaceous Aquitanian lower Miocene *Cenozoic Aragonian Miocene Central Polish Glaciation Pleistocene Archean Precambrian Chadronian upper Eocene Arenigian Lower Ordovician Chalcolithic Cenozoic Argovian Upper Jurassic Champlainian Middle Ordovician Arikareean Tertiary Changhsingian Lopingian Ariyalur Stage Upper Cretaceous Chattian upper Oligocene Artinskian Cisuralian Chazyan Middle Ordovician Asbian Lower Carboniferous Chesterian Upper Mississippian Ashgillian Upper Ordovician Cimmerian Pliocene Asselian Cisuralian Cincinnatian Upper Ordovician Astian upper -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2018/07 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age GSSP GSSP GSSP GSSP EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon Erathem / Era System / Period GSSA age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 541.0 ±1.0 U/L Meghalayan 0.0042 Holocene M Northgrippian 0.0082 Tithonian Ediacaran L/E Greenlandian 152.1 ±0.9 ~ 635 Upper 0.0117 Famennian Neo- 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic ~ 720 Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian Callovian 1000 Quaternary Gelasian 166.1 ±1.2 2.58 Bathonian 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Middle 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Bajocian 170.3 ±1.4 Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Devonian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.63 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Proterozoic Neogene Sinemurian Langhian 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- 2050 Burdigalian Hettangian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 27.82 Gorstian