(Paraguay). (2010) Directed by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY at the CROSSROADS of SPANISH and ENGLISH in 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO Jackelyn Van Buren Doctoral Student, Linguistics

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Linguistics ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fall 11-15-2017 CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY AT THE CROSSROADS OF SPANISH AND ENGLISH IN 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO Jackelyn Van Buren Doctoral Student, Linguistics Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds Part of the Anthropological Linguistics and Sociolinguistics Commons, and the Phonetics and Phonology Commons Recommended Citation Van Buren, Jackelyn. "CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY AT THE CROSSROADS OF SPANISH AND ENGLISH IN 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO." (2017). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/ling_etds/55 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Linguistics ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jackelyn Van Buren Candidate Linguistics Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Chris Koops, Chairperson Dr. Naomi Lapidus Shin Dr. Caroline Smith Dr. Damián Vergara Wilson i CUASI NOMÁS INGLÉS: PROSODY AT THE CROSSROADS OF SPANISH AND ENGLISH IN 20TH CENTURY NEW MEXICO by JACKELYN VAN BUREN B.A., Linguistics, University of Utah, 2009 M.A., Linguistics, University of Montana, 2012 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico December 2017 ii Acknowledgments A dissertation is not written without the support of a community of peers and loved ones. Now that the journey has come to an end, and I have grown as a human and a scholar and a friend throughout this process (and have gotten married, become an aunt, bought a house, and gone through an existential crisis), I can reflect on the people who have been the foundation for every change I have gone through. -

Searching for the Origins of Uruguayan Fronterizo Dialects: Radical Code-Mixing As “Fluent Dysfluency”

Searching for the origins of Uruguayan Fronterizo dialects: radical code-mixing as “fluent dysfluency” JOHN M. LIPSKI Abstract Spoken in northern Uruguay along the border with Brazil are intertwined Spanish-Portuguese dialects known to linguists as Fronterizo `border’ dialects, and to the speakers themselves as portuñol. Since until the second half of the 19th century northern Uruguay was populated principally by monolingual Portuguese speakers, it is usually assumed that Fronterizo arose when Spanish-speaking settlers arrived in large numbers. Left unexplained, however, is the genesis of morphosyntactically intertwined language, rather than, e.g. Spanish with many Portuguese borrowings or vice versa. The present study analyzes data from several communities along the Brazilian border (in Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay), where Portuguese is spoken frequently but dysfluently (with much involuntary mixing of Spanish) by Spanish speakers in their dealings with Brazilians. A componential analysis of mixed language from these communities is compared with Uruguayan Fronterizo data, and a high degree of quantitative structural similarity is demonstrated. The inclusion of sociohistorical data from late 19th century northern Uruguay complements the contemporary Spanish-Portuguese mixing examples, in support of the claim that Uruguayan Fronterizo was formed not in a situation of balanced bilingualism but rather as the result of the sort of fluid but dysfluent approximations to a second language found in contemporary border communities. 1. Introduction Among the languages of the world, mixed or intertwined languages are quite rare, and have provoked considerable debate among linguists. The most well- known cases, Michif, combining French and Cree (Bakker and Papen 1997; Bakker 1996), and Media Lengua, combining Spanish and Quechua (Muysken 1981, 1989, 1997), rather systematically juxtapose lexical items from a European language and functional items from a Native American language, in Journal of Portuguese Linguistics, 8-1 (2009), 3-44 ISSN 1645-4537 4 John M. -

Estudio De Impacto Ambiental Preliminar

ESTRUCTURAS SRL EDIFICIO DE DEPARTAMENTOS ASUNCION - PARAGUAY ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL PRELIMINAR CONSULTOR: ING. JOSÉ ORTIZ GUERRERO MAYO 2016 EDIFICIOS DE DEPARTAMENTOS ESTUDIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL PRELIMINAR 1. INTRODUCCION La empresa ESTRUCTURA SRL se encuentra en etapa de proyecto, un Edificio de Departamentos en un predio localizado sobre la calle Juan Pablo Gorostiaga casi Tte 1ro Nicolás Cazenave de la ciudad de Asunción, Capital. El Edificio en su conjunto ocupará una superficie total de 3.873 m2, desarrollado en un edificio con subsuelo, planta baja y 5 plantas en altura. La superficie total de la finca asiento del proyecto es de 822.75 m2. En términos edilicios, la idea es proponer un edificio de última generación, que incorpore todos los avances tecnológicos de fin de siglo; a ser localizado sobre la calle citada que se encuentra en las cercanías de la Avda. Madame Lynch que constituye uno de los accesos principales a las importantes Avdas. Mcal López, a la Avda Mcal. Estigarribia, a la Avda. Aviadores del Chaco y la Avda. Transchaco, contribuyendo de esta manera con el desarrollo de la economía nacional. El inmueble se encuentra ubicado en la zona definida por el Plan Regulador (Ordenanza Municipal Nº 43/94 y sus modificaciones Ord. 182/04) como AREA INDUSTRIAL y los planos del proyecto y del sistema de prevención contra incendios del edificio ya fueron presentados para su Aprobación en la Municipalidad de Asunción La empresa trabaja con asentamiento de técnicos con experiencia reconocida, de forma a asegurar la incorporación tecnológica avanzada y a ofrecer los mejores servicios, tanto de los equipos a ser instalados, como en el adiestramiento de la mano de obra y en la administración del edificio. -

Departamento De Catastro Tecnico De Consultores Ambientales Nombre Y Especializacion, Año De Codigo Apellido Del Maestria O Direccion, Localidad, Item Inscripció C

DEPARTAMENTO DE CATASTRO TECNICO DE CONSULTORES AMBIENTALES NOMBRE Y ESPECIALIZACION, AÑO DE CODIGO APELLIDO DEL MAESTRIA O DIRECCION, LOCALIDAD, ITEM INSCRIPCIÓ C. I. C. N°: TITULO DE GRADO TELEFONO – CELULAR - EMAIL VIGENCIA OBSERVACIÓN CTCA CONSULTOR DEPARTAMENTO N DOCTORADO EN AREAS AMBIENTAL AMBIENTALES CORONEL CAPRINE Nº 158 CHRISTIAN MASTER EN CIENCIAS, AREA Part. 021-585.018, Ofic. 021- INGENIERO E/ TENIENTE BENITEZ Y 10 1 1.995 I- 002 SANTIAGO BOGADO 428.301 DE SILVICULTURA Y SUELOS 585.018, Cel. 0984- 516 183, E-mail: 30/08/2018 AGRONOMO DE AGOSTO - SAN ARRUA [email protected] FORESTALES LORENZO - CENTRAL MASTER EN HIGIENE DOCTOR EN Part.: 605.598, Ofic.: Cel.: 0981- ANTONIO GONZALEZ JUAN ESCRIBA INDUSTRIAL Y SALUD 2 1.995 I- 003 341.947 QUIMICA 861.265, Email.: jescriba@highway. RIOBOO N° 750 C/ CHACO 3/02/2016 TICOULAT INDUSTRIAL PUBLICA – CONTROL DE com.py BOREAL – ASUNCION POLUCIÓN. ESPECIALIZACION EN Part.: 0336-272071, Cel.: 0971.811- CAMPEONES DEL 65 N°1180 EDELMIRO RUIZ INGENIERO GESTION AMBIENTAL PARA 3 1.995 I-010 378.379 417 0971-811.417 ; EMAIL: C/BRASIL-PEDRO JUAN 13/06/2018 DIAZ VILLALBA AGRONOMO EL DESARROLLO [email protected] CABALLERO -AMAMBAY SOSTENIBLE CESAR AUGUSTO ESPECIALIZACION EN Ofic.: 440-395, Cel.: 0991-719.445 4 1.995 I-013 DOMINGUEZ 230.621 INGENIERO CIVIL IMPACTO Y GESTION *** 14/08/2016 Eamil: [email protected] CASOLA AMBIENTAL ESPECIALISTA EN MANUEL Part.: 021-614.634,Cel.: 0981- INGENIERIA AMBIENTAL, SAN MARTIN Nº 134 C/ 5 1.995 I- 015 BARRIENTOS 539.479 INGENIERO CIVIL 456.403, Email.: 1/03/2018 MCAL. -

Nombre Ciudad Direccion Telefono

NOMBRE CIUDAD DIRECCION TELEFONO CASA PARAGUARI ACAHAY Cnel. Valois Rivarola No. 388 c/ Candido Torales 535.20024 J A COMUNICACIONES ACAHAY Avda. Valois Rivarola c/ Canuto Torales (0535)20401 COOP. CREDIVIL LTDA. ALBERDI Mcal. Lopez c/ Valdez Verdun 0780-210-425 COOP. YPACARAI LTDA ALTOS Avda. Dr. Federico Chavez y Mcal. Lopez (0512) 230-083 IDESA ALTOS Varon Coppens y 14 De Mayo (0512) 230173 LIBRERIA LUCAS ALTOS Avda. Federico Chavez esq. Boqueron y Varon Coppens 0981941867/0512-230-163 COPAFI LTDA AREGUA Carlos A. Lopez Nro. 908 esq. Ntra. Sra. De La Candelaria 0291-432455 / 0291-432793/4 COPAFI LTDA AREGUA Avda. De La Residenta Nro. 809 esq. Dr. Blaires 634-072 COPAFI LTDA AREGUA Virgen De La Candelaria c/ Mcal. Estigarribia (0291) 432 793/4 POWER FARMA ARROYOS Y ESTEROS Padre Fidel Maiz 314 c/ 14 Mayo 0510-272060 A.J.S. ADMINISTRACION Y MANDATOS ASUNCION Fulgencio R. Moreno esq. Mexico Nro 509 444-026/498-377 ACCESO FARMA ASUNCION Sacramento 9009 (Supermercado Stock, Frente Al Hospital Central De Ips) (021) 950 731 / (0981) 245 041 AGILPRES S.A. ASUNCION Mexico Nro. 840 c/ Fulgencio R. Moreno 440242/0981-570-120 AGILPRES S.A. ASUNCION Rodriguez De Francia No. 1521 c/ Avda. Peru 021 221-455 AGROFIELD ASUNCION Avda. Choferes Del Chaco No. 1449 c/ 25 De Mayo 608-656 AMERICAN SCHOOL OF ASUNCION ASUNCION Sargento Marecos c/Espana 603518 Int1 AMPANDE ASUNCION Padre Cardozo 334 c/ De Las Residentas 205 - 312 / 0991-207-326 ASOCIACION DEL PERSONAL DEL BCP ASUNCION Pablo Vi I e/ Sargento Marecos 619-2650 ATALAYA DE INMUEBLES ASUNCION Avda. -

UC Berkeley Comparative Romance Linguistics Bibliographies

UC Berkeley Comparative Romance Linguistics Bibliographies Title Comparative Romance Linguistics Bibliographies, vol. 62 (2013) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/03j8g8tt Author Imhoff, Brian Publication Date 2013 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Comparative Romance Linguistics Bibliographies Volume 62 (2013) Contents Brianna Butera, “Current studies in general Romance linguistics,” 1-17. Brian Imhoff, “Current studies in Romanian linguistics,” 18-57. Fernando Tejedo-Herrero, “Current studies in Spanish linguistics,” 58-117. Previous issues and a brief history of the CRLB/CRLN may be consulted at: http://hisp462.tamu.edu/CRLB/. Contributors Brianna Butera Department of Spanish and Portuguese University of Wisconsin-Madison [email protected] Brian Imhoff Department of Hispanic Studies Texas A&M University [email protected] Fernando Tejedo-Herrero Department of Spanish and Portuguese University of Wisconsin-Madison [email protected] Current Studies in General Romance Linguistics Comparative Romance Linguistics Bibliographies Volume 62 (2013) Brianna Butera University of Wisconsin-Madison Abad Nebot, Francisco. 2011. Del latín a los romances ibéricos. Epos 27: 267-294. Aboh, Enoch, Elisabeth van der Linden, Josep Quer, and Petra Sleeman (eds). 2009. Romance languages and linguistic theory 2007, Selected papers from ‘Going Romance’ Amsterdam 2007. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Abraham, Werner, and Cláudio C. e C. Gonçalvez. 2011. Non-state imperfective in Romance and West- Germanic: How does Germanic render the progressive? Cahiers Chronos 22: 1-20. Acedo-Matellan, Victor, and Jaume Mateu. 2013. Satellite-framed Latin vs. verb-framed romance: a syntactic approach. Probus: International Journal of Latin and Romance Linguistics 25.2: 227- 266. Acosta, Diego de. 2011a. -

Edificios Bernardino

REPÚBLICA DEL PARAGUAY RELATORIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL EDIFICIOS BERNARDINO Consultor Ambiental: Ing. Amb. Jorge A. Bernal Segovia 2016 ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDO I. ANTECEDENTES ................................................................................................................. 1 II. OBJETIVOS ............................................................................................................................. 2 Objetivo General: .......................................................................................................................... 2 Objetivos Específicos ................................................................................................................... 2 III. ÁREA DEL ESTUDIO ...................................................................................................... 4 Área de influencia directa (AID) ................................................................................................. 4 Área de influencia indirecta (AII): .............................................................................................. 5 IV. ALCANCE DE LA OBRA ................................................................................................ 5 IV-1- DESCRIPCIÓN DEL PROYECTO PROPUESTO .................................................. 5 IV -2- DESCRIPCIÓN DEL MEDIO AMBIENTE: ........................................................... 9 IV -3- DETERMINACION DE LOS POTENCIALES IMPACTOS DEL PROYECTO. ............................................................................................................................. -

Instituto Nacional De Cooperativismo - Directorio Actual - Enero 2010

Instituto Nacional de Cooperativismo - Directorio Actual - Enero 2010 Tipo Sector Nombre de Cooperativa Ciudad Dirección Dpto. Teléfono CA10 DE DICIEMBRE C.M.A.C.Co.S. L. Asunción Alberdi 320 e/ Palma y Estrella. Ofic. 407 Central 493 499 CA12 DE JULIO M.A.C.Co.P.S. de Emp. y Obr. del Gremio Aut. Maq. y Afin. Asunción Mac Mahon 5638 c/ Rca. Argentina - Emp. Exinchaco Capital 615919 / 600398 BA12 DE JUNIO C.A.C.Co.S. Emp. del C.A.H. L. Asunción Carios N° 362 Capital 5690 165-166 CA13 DE JUNIO C.M.A.C.Co.T.P.S. Asunción Testava 2266 e/ Guillermo Arias y Cnel. Gracia. Capital 480276 - Fax: 426.220 CP14 DE MAYO C. M. de P. Agro. Co. y S. L. Hernadarias Colonia Tembiaporá Resistencia Alto Paraná CA15 DE DICIEMBRE M.C.A.S. Capiatá Compañía 9 - Barrio Caacupémi Central 0228 635147 BD16 de NOVIEMBRE C.M. L. Asunción Reservistas de la Guerra del Chaco N° 3.552 y Overava Capital 282.370 AD17 DE MAYO L. C. M. de Co .S. del Pers. Pcial. Asunción Pte. Franco 638e/ 15 de Agosto y O´Leary Capital 493-806 - Fax. 493-923 BD19 DE MARZO C. M. A. C. P. C. S. Villa Elisa Tte. Américo Picco 2742 c/ Von Poleski Central 942.495 / 944.075 CA21 DE SETIEMBRE L. C.M.A.C.Co.P.Agroind.S. San Juan Bautista Monseñor Rojas e/ Mcal. López y Victor Z. Romero Misiones 081-213 070 CA23 de OCTUBRE L. C.M.A.C.T.P.Co.V.S. -

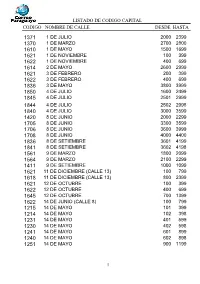

Listado De Codigo Capital Codigo Nombre De Calle

LISTADO DE CODIGO CAPITAL CODIGO NOMBRE DE CALLE DESDE HASTA 1371 1 DE JULIO 2000 2399 1370 1 DE MARZO 2700 2800 1610 1 DE MAYO 1500 1699 1621 1 DE NOVIEMBRE 100 399 1622 1 DE NOVIEMBRE 400 699 1614 2 DE MAYO 2600 2999 1621 3 DE FEBRERO 200 399 1622 3 DE FEBRERO 400 699 1836 3 DE MAYO 3800 3999 1850 4 DE JULIO 1600 2499 1845 4 DE JULIO 2501 2999 1844 4 DE JULIO 2502 2998 1840 4 DE JULIO 3000 3599 1420 8 DE JUNIO 2000 2299 1705 8 DE JUNIO 3300 3599 1706 8 DE JUNIO 3600 3999 1708 8 DE JUNIO 4000 4400 1836 8 DE SETIEMBRE 3601 4199 1841 8 DE SETIEMBRE 3602 4198 1561 9 DE MARZO 1800 2099 1564 9 DE MARZO 2100 2299 1411 9 DE SETIEMBRE 1000 1099 1621 11 DE DICIEMBRE (CALLE 13) 100 799 1618 11 DE DICIEMBRE (CALLE 13) 800 2399 1621 12 DE OCTUBRE 100 399 1622 12 DE OCTUBRE 400 699 1645 12 DE OCTUBRE 700 1399 1622 14 DE JUNIO (CALLE 8) 100 799 1215 14 DE MAYO 101 399 1214 14 DE MAYO 102 398 1231 14 DE MAYO 401 599 1230 14 DE MAYO 402 598 1241 14 DE MAYO 601 899 1240 14 DE MAYO 602 898 1251 14 DE MAYO 900 1199 1 LISTADO DE CODIGO CAPITAL CODIGO NOMBRE DE CALLE DESDE HASTA 1261 14 DE MAYO 1201 1699 1260 14 DE MAYO 1202 1698 1264 14 DE MAYO 1701 2799 1271 14 DE MAYO 1702 2698 1270 14 DE MAYO 2702 3598 1265 14 DE MAYO 2801 3599 1214 15 DE AGOSTO 101 399 1211 15 DE AGOSTO 102 398 1230 15 DE AGOSTO 301 599 1225 15 DE AGOSTO 302 598 1240 15 DE AGOSTO 601 899 1235 15 DE AGOSTO 602 898 1251 15 DE AGOSTO 901 1199 1255 15 DE AGOSTO 902 1198 1260 15 DE AGOSTO 1200 1699 1271 15 DE AGOSTO 1700 2699 1270 15 DE AGOSTO 2700 3399 1370 18 DE JULIO (E/ ESPERANZA Y PIZARRO) 2000 2099 1368 18 DE JULIO (E/ F. -

Situación Epidemiológica De Arbovirosis

Situación epidemiológica de Arbovirosis XVIII REGION SANITARIA-CAPITAL ACTUALIZACIÓN DESDE LA SE1 A LA SE22 (29 de diciembre, 2019 al 30 de mayo, 2020) AÑO 2020 Descripción Este boletín contiene información actualizada de la Situación Epidemiológica de Arbovirosis: Dengue, Zika y Chikungunya. Los datos presentados, tienen como fuente principal la base nacional de la Vigilancia de Arbovirosis. La revisión final y difusión de las informaciones, aquí presentadas, son realizadas por el equipo técnico de la Dirección de Alerta y Respuesta ante Emergencias en Salud Pública /Centro Nacional de Enlace (CNE). Contenido Resumen Situación Epidemiológica departamental Dengue Chikungunya Zika Circulación Viral Consideraciones finales PÁGINA 1 SITUACIÓN EPIDEMIOLÓGICA DE LA XVIII REGIÓN SANITARIA-CAPITAL Asunción cuenta con 68 barrios, 29% (20/68) de los barrios registran notificaciones en este periodo, con promedio de 9 notificaciones en las últimas cuatro semanas. TABLA 1: RESUMEN Desde el 29 de diciembre 2019 al 30 de mayo 2020 se registran: ASUNCIÓN AÑO 2.020 CASOS SOSPECH DESCARTAD (CONF. Y ARBOVIROSIS OSOS OS PROB.) DE NGUE 30.805 11.738 201 CHIKUNGUNYA 0 50 4 ZIKA 0 72 23 No se registran casos confirmados ni probables de Chikungunya y Zika, en lo que va del año 2020. TABLA 2: CASOS DE DENGUE POR BARRIOS DE ASUNCIÓN ASUNCIÓN AÑO 2020 CASOS (CONF. Y BARRIO SOSPECHOSOS DESCARTADOS PROB.) SIN DATOS DE BARRIO 79 4.637 16 TACUMBU 10 1011 5 SANTA ANA 442 459 3 VILLA AURELIA 179 458 3 ROBERTO L. PETIT 618 424 3 SANTA MARIA 6 368 SANTISIMA TRINIDAD 2.867 359 13 VISTA ALEGRE 484 247 4 VIRGEN DE FATIMA 5 241 2 JARA 1.215 219 6 RICARDO BRUGADA 1.010 204 7 RECOLETA 94 185 1 MADAME ELISA ALICIA LINCH 3 173 MARISCAL JOSE FELIX ESTIGARRIBIA 6 147 MBURICAO 72 139 2 TERMINAL 50 132 3 BAÑADO CARA CARA 4 119 1 LA CATEDRAL 3 118 GENERAL BERNARDINO CABALLERO 345 113 2 BANCO SAN MIGUEL 36 110 2 PRESIDENTE CARLOS ANTONIO LOPEZ 0 110 1 PÁGINA 2 ASUNCIÓN AÑO 2020 CASOS (CONF. -

Al Atender El Teléfono En Una Dependencia Policial Debemos Tener En Cuenta Lo Siguiente

Al atender el teléfono en una Dependencia Policial debemos tener en cuenta lo siguiente: _ Identificarse correctamente mencionando la dependencia a que pertenecemos dando nuestro grado y nombre. – Tener siempre papel y lápiz para anotar los mensajes o pedidos que se realizan. – Atender con corrección y cortesía, dando respuestas claras, rápidas y eficientes, la persona que llama a la policía es porque necesita de nuestros servicios y puede encontrarse en una situación de emergencia. – Al realizar un pedido no olvide el POR FAVOR y al concluir la conversación recuerde decir GRACIAS. – En dependencias policiales al hacer llamados de índole personal, utilice la línea telefónica por breves instantes y si es posible, solo en caso de urgencia. – Una buena atención es sinónimo de educación y corrección. Guía Telefónica de la Policía Nacional 1 Departamento de Comunicaciones COMANDANCIA DE LA POLICÍA NACIONAL (C. P. N.) (Pyo. Independiente 289 e/ Chile y Ntra. Sra. de la Asunción) COMANDANCIA 445.858 (Fax) 446.828 C.T. 441.355 - Int. 222 Gabinete C.T. 441.355 - Int 265 Ayudantia (Fax) 445.107 C.T. 441.355 - Int. 226 Asesores: 441.617 DEPARTAMENTO DE ENLACE CON EL PARLAMENTO NACIONAL (Avda. República y 14 de Mayo) Jefatura - Ayudantía 414.5199 DEPARTAMENTO DE ASUNTOS INTERNACIONALES Y AGREGADURÍAS POLICIALES (Pyo. Independiente 289 e/ Chile y Nuestra Sra. De la Asunción) Jefatura 497.725 - C.T. 441.355 Interno 268 Ayudantia 446.828 - C.T. 441.355 Interno 270 Correo Electrónico: [email protected] DEPARTAMENTO DE RELACIONES PÚBLICAS (Presidente Franco e/Chile) Jefatura (Fax) 492.515 Sección Prensa (Fax) 446.105 Guardia (Fax) 445.109 Jefatura Int 214 Guardia Int 208 Correo Electrónico: [email protected] DEPARTAMENTO DE CEREMONIAL Y PROTOCOLO (Paraguayo Independiente c/Chile) Jefatura 493.815 Ayudantía C.T.441.355 - Int. -

Proyecto “Construcción Del Edificio De Departamentos – Ykuá Satí”

RELATORIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL * Ley Nº 294/93 “Evaluación de Impacto Ambiental” Decreto Reglamentario Nº 453/13 y 954/13 PROYECTO “CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL EDIFICIO DE DEPARTAMENTOS – YKUÁ SATÍ”. PROPONENTE: Paraguay One S.A. DIRECCIÓN DEL PROYECTO: Calle: Dr. Jaime Bestard y Mayor Evasio Merlo Barrio: San Jorge. Distrito: La Recoleta Cuentas Corrientes Catastrales Nº: 14-1545-17. CONSULTORA AMBIENTAL Consultora de Gestión Ambiental S.A. Registro MADES - CTCA – E-135. Teléfono: (021) 66 51 07 www.cgambiental.com.py -AÑO 2019- RELATORIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL PROYECTO: “CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL EDIFICIO DE DEPARTAMENTOS - YKUÁ SATÍ”. PÁGINA: 2 INDICE DE CONTENIDO CAPITULO 1: Caracterización del proyecto 1.1.- Nombre del proyecto 1.2.- Tipo de actividad 1.3.- Datos del proponente 1.4.- Datos del área del proyecto 1.5.- Ubicación del emprendimiento 1.6.- Descripción del Proyecto Propuesto 1.7.- Materia prima e insumos 1.8.- Recursos humanos 1.9.- Desechos. Estimación. Características 1.10.- Cronograma de ejecución del proyecto CAPITULO 2: Marco legal 2.1.- Vinculación con las normativas ambientales. CAPITULO 3: Definición del área de influencia del proyecto 3.1.- Descripción de factores físicos 3.2.- Descripción del aspecto biológico 3.3.- Descripción del aspecto antrópico CAPITULO 4: Plan de gestión ambiental 4.1.- Plan de mitigación para atenuar los impactos ambientales negativos 4.2.- Plan de monitoreo 4.3.- Tabla de medidas de mitigación y plan de monitoreo 4.4.- Cronograma de implementación de las medidas de mitigación CAPITULO 5: Conclusiones PROPONENTE: PARAGUAY ONE S.A. CONSULTORA: CONSULTORA DE GESTION AMBIENTAL S.A. Registro MADES CTCA – E – 135. RELATORIO DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL PROYECTO: “CONSTRUCCIÓN DEL EDIFICIO DE DEPARTAMENTOS - YKUÁ SATÍ”.