Rare and Curious Specimens, an Illustrated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 1 Sydney Harbour: Its Diverse Biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings

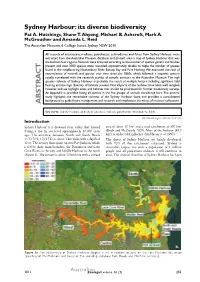

Sydney Harbour: its diverse biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings, Shane T. Ahyong, Michael B. Ashcroft, Mark A. McGrouther and Amanda L. Reid The Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010 All records of crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms and fishes from Sydney Harbour were extracted from the Australian Museum database, and plotted onto a map of Sydney Harbour that was divided into four regions. Records were analysed according to the number of species, genera and families present and over 3000 species were recorded, approximately double to triple the number of species found in the neighbouring Hawkesbury River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking. We examined the rate of accumulation of records and species over time since the 1860s, which followed a stepwise pattern usually correlated with the research activity of specific curators at the Australian Museum. The high species richness of Sydney Harbour is probably the result of multiple factors including significant tidal flushing and the high diversity of habitats present. Not all parts of the harbour have been well sampled, however, and we highlight areas and habitats that should be prioritised for further biodiversity surveys. An Appendix is provided listing all species in the five groups of animals considered here. The present study highlights the remarkable richness of the Sydney Harbour fauna and provides a consolidated background to guide future management and research, and emphasises the values of museum collections. ABSTRACT Key words: Sydney Harbour, diversity, crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms, fishes http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2012.031 Introduction Sydney Harbour is a drowned river valley that formed area of about 50 km2 and a total catchment of 500 km2 during a rise in sea level approximately 10,000 years (Birch and McCready 2009). -

Obituary. Edward Pierson Ramsay

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Etheridge Jr, R., 1917. Obituary—Edward Pierson Ramsay, LL.D. Curator, 22nd September, 1874 to 31st December, 1894. Records of the Australian Museum 11(9): 205–217. [28 May 1917]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.11.1917.916 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia OBITUARY: EDWARD PIERSON RAMSAY, LI~.D. Curator, 22nd S'eptember, 1874 to 31st December, 1894. Dr. E. P. Ramsay was the third son of David Ramsay, M.D., the owner of the DobroYd Estate,Dobl'oyd POlnt,Long Cove. He was born at Dobroyd House on 3rd ,December ,1842, andwas,therefoi'e, in his 75th year at the time of his death. His ed ucation took place at St; Mark's Collegiate School, first at Darling Point and later at Macquarie Fields, presided over by tbeRev. G.F. Macarthur,who later became HeadMaster of The King's School, Parramatta. In 1863,. Mr. Ramsay matriculated at the University, and (in the same yeaI') also entered asa stud.ent of St. Paul's College. His name remained on the list of members of the University until December, 1865. In apportioni~lgthe Dobroyd Estate amqngstthe children 'of Dr. David. Ramsay, the large~nd beautiful garden was aUottedtothe subject oE this notice; arid cameilito his hands about the year 1867. He forthwith opened the Dobroyd New Plant and Seed . -

Ecology of Pyrmont Peninsula 1788 - 2008

Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Sydney, 2010. Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula iii Executive summary City Council’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030’ initiative ‘is a vision for the sustainable development of the City for the next 20 years and beyond’. It has a largely anthropocentric basis, that is ‘viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values’(Macquarie Dictionary, 2005). The perspective taken here is that Council’s initiative, vital though it is, should be underpinned by an ecocentric ethic to succeed. This latter was defined by Aldo Leopold in 1949, 60 years ago, as ‘a philosophy that recognizes[sic] that the ecosphere, rather than any individual organism[notably humans] is the source and support of all life and as such advises a holistic and eco-centric approach to government, industry, and individual’(http://dictionary.babylon.com). Some relevant considerations are set out in Part 1: General Introduction. In this report, Pyrmont peninsula - that is the communities of Pyrmont and Ultimo – is considered as a microcosm of the City of Sydney, indeed of urban areas globally. An extensive series of early views of the peninsula are presented to help the reader better visualise this place as it was early in European settlement (Part 2: Early views of Pyrmont peninsula). The physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula has been transformed since European settlement, and Part 3: Physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula describes the geology, soils, topography, shoreline and drainage as they would most likely have appeared to the first Europeans to set foot there. -

Heritage Collection

H ERITAGEC OLLECTION N ELSON M EERS F OUNDATION 2005 STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES H ERITAGEC OLLECTION N ELSON M EERS F OUNDATION 2005 STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES www.sl.nsw.gov.au/heritage/ Foreword State Library of New South Wales The Nelson Meers Foundation Heritage Collection following their liberation in 1945, reminds us Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 opened in 2003, with the aim of displaying of the horrors of that period of European history Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 a selection of the State Library’s finest items. and of the constant humanitarianism that works TTY (02) 9273 1541 These represent some of history’s greatest through our society. Australia’s craft traditions are Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au individual endeavours and highest intellectual represented in a beautiful display of silver items, achievements. For the following decade, the and we again return to the foundations and Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Heritage Collection will show an array of rare, development of the colony with displays of and selected public holidays famous and historically significant items from William Bradley’s charts and of materials relating Gallery space created by Jon Hawley the State Library’s world-renowned collections. to Governor Lachlan Macquarie. Project Manager: Phil Verner Coordinating Curator: Stephen Martin Public response over the last two years has been Curators and other experts will continue the Curators: Louise Anemaat, Ronald Briggs, Cheryl Evans, enthusiastic. Now, as we are entering the third popular series of events relating to the Heritage Mark Hildebrand, Warwick Hirst, Melissa Jackson, Richard Neville, year of the exhibition, this interest continues Collection. -

Aboriginal History Journal

Aboriginal History Volume Fifteen 1991 ABORIGINAL HISTORY INCORPORATED The Committee of Management and the Editorial Board Peter Read (Chair), Peter Grimshaw (Treasurer/Public Officer), May McKenzie (Secretary/Publicity Officer), Robin Bancroft, Valerie Chapman, Niel Gunson, Luise Hercus, Bill Jonas, Harold Koch, C.C. Macknight, Isabel McBryde, John Mulvaney, Isobel White, Judith Wilson, Elspeth Young. ABORIGINAL HISTORY 1991 Editors: Luise Hercus, Elspeth Young. Review Editor: Isobel White. CORRESPONDENTS Jeremy Beckett, Ann Curthoys, Eve Fesl, Fay Gale, Ronald Lampert, Andrew Markus, Bob Reece, Henry Reynolds, Shirley Roser, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Shaw, Tom Stannage, Robert Tonkinson, James Urry. Aboriginal History aims to present articles and information in the field of Australian ethnohistory, particularly in the post-contact history of the Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. Historical studies based on anthropological, archaeological, linguistic and sociological research, including comparative studies of other ethnic groups such as Pacific Islanders in Australia, will be welcomed. Future issues will include recorded oral traditions and biographies, narratives in local languages with translations, previously unpublished manuscript accounts, r6sum6s of current events, archival and bibliographical articles, and book reviews. Aboriginal History is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material in the journal. Views and opinions expressed by the authors of signed articles and reviews are not necessarily shared by Board members. The editors invite contributions for consideration; reviews will be commissioned by the review editor. Contributions and correspondence should be sent to: The Editors, Aboriginal History, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University, GPO Box 4, Canberra, ACT 2601. Subscriptions and related inquiries should be sent to BIBLIOTECH, GPO Box 4, Canberra, ACT 2601. -

H Eritagecollection

H ERITAGEC OLLECTION N E L S O N M E E R S F O U N D A T I O N 2006 S T A T E L I B R A R Y O F N E W S O U T H W A L E S H ERITAGEC OLLEcTION N E L S O N M E E R S F O U N D A T I O N 2006 S T A T E L I B R A R Y O F N E W S O U T H W A L E S www.atmitchell.com State Library of New South Wales Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.atmitchell.com Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Gallery space created by Jon Hawley Project Manager: Phil Verner Coordinating Curator: Stephen Martin Curators: Louise Anemaat, Suzanne Bennett, Ron Briggs, Cheryl Evans, Mark Hildebrand, Warwick Hirst, Melissa Jackson, Meredith Lawn, Jennifer MacDonald, Richard Neville, Jennifer O’Callaghan, Maggie Patton, Margot Riley, Kerry Sullivan Editors: Helen Cumming, Theresa Willsteed Graphic Design: Andrew Woodward Preservation Project Leaders: Anna Brooks and Nichola Parshall All photographic/imaging work is by Phong Nguyen, Kate Pollard and Scott Wajon, Imaging Services, State Library of New South Wales Printer: Penfold Buscombe, Sydney Paper: Spicers Impress Matt 300 gsm and 130 gsm Print run: 11 000 P&D-1747-1/2006 ISBN 0 7313 7157 7 ISSN 1449-1001 © State Library of New South Wales, January 2006 The State Library of NSW is a statutory authority of, and principally funded by, the NSW State Government. -

Steam Trawling on the South-East Continental Shelf of Australia an Environmental History of Fishing, Management and Science in NSW, 1865 – 1961

Steam trawling on the south-east continental shelf of Australia An environmental history of fishing, management and science in NSW, 1865 – 1961 Submitted to fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy, School of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Tasmania Anne Lif Lund Jacobsen August 2010 Abstract As many of the world‘s fish stocks are fully or over-exploited there is an urgent need for governments to provide robust fisheries management. However, governments are often slow to implement necessary changes to fisheries practices. The will to govern is an essential factor in successful marine resource management. Studies of historical documents from State and Commonwealth fisheries authorities involved in the steam trawl fishery on the south-east continental shelf of Australia illustrate different expressions of intentional management and how a more ecological responsible view has emerged. Motivated by Sydney‘s insufficient supplies of fish, the objective of early fisheries management in the state of New South Wales (NSW) was to improve the industry. Driven by state developmentalism, efforts were focused on increasing the productivity of already existing coastal fisheries through fisheries legislation, marine hatching and marketing. As this failed, an alternative development vision emerged of exploiting the untouched resources on the continental shelf, which at the time were believed to be inexhaustible. During 1915 to 1923 the NSW Government pioneered steam trawling on the shelf through the State Trawling Industry with the aim of providing the public with an affordable supply of fish. Although an economic failure, the State Trawling Industry paved the way for a private steam trawling industry. -

Fulton Petrogale.Indd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online New Information about the Holotype, in the Macleay Museum, of the Allied Rock-wallaby Petrogale assimilis Ramsay, 1877 (Marsupialia, Macropodidae) GRAHAM R. FULTON School of Veterinary and Life Sciences, Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch WA 6150, Australia Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, The University of Queensland, Brisbane Qld 4072, Australia ([email protected]) Published on 12 July 2016 at http://escholarship.library.usyd.edu.au/journals/index.php/LIN Fulton, G.R. (2016). New information about the holotype, in the Macleay Museum, of the Allied Rock- Wallaby Petrogale assimilis Ramsay, 1877 (Marsupialia, Macropodidae). Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 138: 57-58. The location of the missing holotype of the Allied Rock-wallaby Petrogale assimilis is given as the Macleay Museum. Background information about its collection during the Chevert Expedition of 1875, obtained from Sir William Macleay’s personal journal, sheds further light on the history of this important specimen. Manuscript received 12 April, accepted for publication 25 June 2016. Keywords: Chevert Expedition, Macleay Museum, Nyawaygi people, type specimens. DISCUSSION The two specimens referred to by Ramsay (1877a, 1877b) were collected during the Chevert Type specimens serve as the physical reference Expedition in 1875 (Fulton 2012). Macleay’s point for a particular taxon. Most holotypes are single collectors George Masters, Edward Spalding and Dr specimens upon which the description and name of W. H. James collected the specimens, inland on the a species is based (ICZN 1999). -

1 Universitetsbiblioteket Lunds Universitet Samling Nordstedt, Otto

1 Universitetsbiblioteket Lunds universitet Samling Nordstedt, Otto Nordstedt, Otto, f. 20 januari 1838, d. 6 februari 1924, lärjunge till Jacob Agardh. Professors namn år 1903, filosofie hedersdoktor vid Lunds universitet, konservator och bibliotekarie vid Lunds botaniska institut, ledamot av Vetenskapsakademien. Hans fader fältläkaren Carl P. U. Nordstedt, f. 1793, hade disputerat för Linné-lärjungen Carl P. Thunberg och var son till en dotter till Carl von Linnés bror Samuel Linnæus. Från 1871 självfinansierad utgivare av Botaniska notiser. Utgav Index Desmidiacearum och, med Johan Wahlstedt, Characeæ Scandinaviæ exsiccatæ, samt Algæ aquæ dulcis exsiccatæ (med Veit Wittrock och Gustaf Lagerheim). Arkivets omfång i hyllmeter: 4,8 hm Proveniensuppgifter: Donation till Botaniska institutionen enligt Otto Nordstedts testamente Allt material har samlats i denna förteckning. Beträffande autografsamlingen följer den alfabetiska ordningen ännu den princip efter vilken autografsamlingen skapades, nämligen som handstilsprover. Restriktioner för tillgänglighet: Nej. Ordnandegrad: Arkivet är i huvudsak ordnat. Arkivöversikt: Vol. 1 Brev från Otto Nordstedt 2-23 Brev till Otto Nordstedt från skandinaviska botanister 24-34 Brev till Otto Nordstedt från utländska brevskrivare 35-37 Övriga brev, biografika, fotografier samt auktionskatalog och övrigt tryck 38-67 Autografsamling (handstilsprover) med äldre förteckningar 68 Manuskript, växtprover, oordnade växtetiketter 69-70 Fotostatkopior, tomma kuvert 71-72 Katalog över avhandlingar 2 Vol. 1 Brev från Otto Nordstedt, till: Bohlin, Knut H. (1869-1956), fil. dr., lektor i biologi och kemi i Stockholm 1903, odat. (1, 1 anteckn.) Chifflot, Julien (1867-c1924), inspecteur phytopathologique de la region, professeur adjoint à la Faculté des sciences de Lyon, sous-directeur du jardin botanique au Parc de la tête d’Or (Frankrike) [1902] (1 konc.) Eulenstein, Theodor E. -

A Monument for the Nation: the Australian Encyclopaedia (1925/26)

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2007 A monument for the nation : the ”Australian Encyclopaedia” (1925/26) Kavanagh, Nadine Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-163657 Dissertation Published Version Originally published at: Kavanagh, Nadine. A monument for the nation : the ”Australian Encyclopaedia” (1925/26). 2007, University of Zurich, Faculty of Arts. A Monument for the Nation: the Australian Encyclopaedia (1925/26) Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Zurich for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Nadine Kavanagh of Baar / Zug Accepted in the autumn semester 2007 on the recommendation of Prof. Dr. Madeleine Herren and Prof. Dr. Ian Tyrrell Sydney 2007 Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................4 1 THE SOFT POWER OF THE ENCYCLOPAEDIC GENRE ............................................15 1.1 THEORY AND HISTORY OF ENCYCLOPAEDIAS ...................................................................15 1.2 ENCYCLOPAEDIAS FROM A POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE .......................................................22 2 AUSTRALIA AND THE CORE OF NATION BUILDING................................................29 2.1 THEORETICAL APPROACHES TO NATION BUILDING..........................................................29 -

Aspects of the Career of Alexander Berry, 1781-1873 Barry John Bridges University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Aspects of the career of Alexander Berry, 1781-1873 Barry John Bridges University of Wollongong Bridges, Barry John, Aspects of the career of Alexander Berry, 1781-1873, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 1992. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1432 This paper is posted at Research Online. 525 LIST OF SOURCES The sources listed here are those used for Berry's life as a whole. No attempt has been made to confine the list to sources mentioned in the reference notes by identifying and deleting sources for chapters on matters not included in this thesis or lost in cutting the text. Item details have been taken, as far as possible, from title pages. As a consequence, in some items usage varies from mine in the text of the thesis. Anonymous items have been placed at the end of sections and listed chronologically by date of publication. Where the author has been identified his name is indicated in square brackets. PRIMARY SOURCES ARCHIVES SCOTTISH RECORD OFFICE, NEW REGISTER HOUSE, EDINBURGH Old Parish Registers OPR 351/2 Errol Births/Marriages 1692 - 1819. OPR 420/3 Cupar Baptisms/Marriages/Deaths 1778 - 1819. OPR 420/4 Cupar OPR 445/1 Leuchars Births/Marriages 1665 - 1819. OPR 445/2 Leuchars Births/Marriages 1820 - 1854, Deaths 1720 - 1854. OPR 446/1 Logie. OPR 446/2 Logie. OPR 453/3 St Andrews and St Leonards Births. Sherriff Court SC 49/31/8 Sheriff Court of Perth - for inventories of estate of James Berrie 10 March 1828. -

A Detailed Report on the Birds Collected on the Chevert Expedition to New Guinea, in 1875

A Detailed Report on the Birds Collected on the Chevert Expedition to New Guinea, in 1875 GRAHAM R. FULTON1, 2 1Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia; and 2Environmental and Conservation Sciences, Murdoch University, South Street, Murdoch, WA 6150, Australia.Email: [email protected] Published on 20 July 2021 at https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/LIN/index Fulton, G. (2021). A detailed report on the birds collected on the Chevert Expedition to New Guinea, in 1875. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 143, 9-36. The birds collected on the Chevert Expedition in 1875 are reported and discussed on the basis of information published in the two seminal papers of George Masters, Edward Pierson Ramsay and unreported specimens found in the Macleay Museum. In addition, the private journals of Lawrence Hargrave and William Macleay, old newspaper articles and the literature emanating from the expedition were searched. The Chevert Expedition collected: at sea, on islands off the Queensland coast, on Torres Strait islands and New Guinea. A total of 877 individual birds, of 193 species are listed and discussed. This total number includes 84 specimens not previously reported plus 6 sight records of species that were not collected. The history of the imprudent and perfi dious management of specimens held by the Macleay Museum, at The University of Sydney, is also reported. In particular, an account of the 36 type specimens, representing 10 species, is given. Most of the surviving types are currently held at The Australian Museum on permanent loan, 12 have been lost and misplaced with 4 of them found in this study.