Australian Museums, Aboriginal Skeletal Remains, and the Imagining of Human Evolutionary History, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creative Foundations. the Royal Society of New South Wales: 1867 and 2017

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, vol. 150, part 2, 2017, pp. 232–245. ISSN 0035-9173/17/020232-14 Creative foundations. The Royal Society of New South Wales: 1867 and 2017 Ann Moyal Emeritus Fellowship, ANU, Canberra, Australia Email: [email protected] Abstract There have been two key foundations in the history of the Royal Society of New South Wales. The first at its creation as a Royal Society in 1867, shaped significantly by the Colonial savant, geologist the Rev. W. B. Clarke, assisted by a corps of pioneering scientists concerned to develop practical sci- entific knowledge in the colony of N.S.W. And the second, under the guidance of President Donald Hector 2012–2016 and his counsellors, fostering a vital “renaissance” in the Society’s affairs to bring the high expertise of contemporary scientific and transdisciplinary members to confront the complex socio-techno-economic problems of a challenging twenty-first century. his country is so dead to all that natures) on a span of topics that embraced “Tconcerns the life of the mind”, the geology, meteorology, climate, mineralogy, scholarly newcomer the Rev. W. B. Clarke the natural sciences, earthquakes, volcanoes, wrote to his mother in England in Septem- comets, storms, inland and maritime explo- ber 1839 shortly after his arrival in New ration and its discoveries which gave singular South Wales (Moyal, 2003, p. 10). But a impetus to the newspaper’s role as a media man with a future, he quickly took up the pioneer in the communication of science offer of the editor ofThe Sydney Herald, John (Organ, 1992). -

Rare and Curious Specimens, an Illustrated

Krefft's successor, Edward Pierson Ramsay (1842-1916), was the first Australian to head the Museum. Son of a prosperous medical practitioner whose assets included the Dobroyd Estate, he grew up in Sydney and, at the age of twenty-one, entered the University of Sydney, itself only twelve years old, with a single faculty and but three professors. He departed two years later without having taken a degree and, at the age of twenty-five established a successful plant and seed nursery on a portion of the Dobroyd Estate inherited from his father. Seven years later, in 1874, he was appointed curator of the Australian Museum. While it is conceivable that such a background might have fitted a native son for a junior position in the Herbarium, it would seem hardly to have provided ade quate preparation for the senior position in an institution devoted to zoology, geology and anthropology and with some international standing for researches in these fields. One must look further for justification of the trustees' faith. As a youth, his keen interest in natural history was cultivated in discussions with Pittard, Sir William Denison, and a German schoolteacher-naturalist, Reitmann. At twenty he became treasurer of the Entomological Society of New South Wales and three years later was elected a Life Fellow of the newly reconstituted Royal Society of New South Wales-an honour which may have more reflected the magnitude of his subscription than his scientific reputation which, at that stage, rested on eight short and rather pedestrian papers on Australian birds. This output might not have justified fellowship of a scientific society but it was a creditable achievement for an undergraduate. -

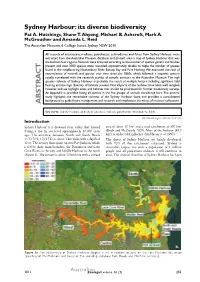

Page 1 Sydney Harbour: Its Diverse Biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings

Sydney Harbour: its diverse biodiversity Pat A. Hutchings, Shane T. Ahyong, Michael B. Ashcroft, Mark A. McGrouther and Amanda L. Reid The Australian Museum, 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010 All records of crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms and fishes from Sydney Harbour were extracted from the Australian Museum database, and plotted onto a map of Sydney Harbour that was divided into four regions. Records were analysed according to the number of species, genera and families present and over 3000 species were recorded, approximately double to triple the number of species found in the neighbouring Hawkesbury River, Botany Bay and Port Hacking. We examined the rate of accumulation of records and species over time since the 1860s, which followed a stepwise pattern usually correlated with the research activity of specific curators at the Australian Museum. The high species richness of Sydney Harbour is probably the result of multiple factors including significant tidal flushing and the high diversity of habitats present. Not all parts of the harbour have been well sampled, however, and we highlight areas and habitats that should be prioritised for further biodiversity surveys. An Appendix is provided listing all species in the five groups of animals considered here. The present study highlights the remarkable richness of the Sydney Harbour fauna and provides a consolidated background to guide future management and research, and emphasises the values of museum collections. ABSTRACT Key words: Sydney Harbour, diversity, crustaceans, molluscs, polychaetes, echinoderms, fishes http://dx.doi.org/10.7882/AZ.2012.031 Introduction Sydney Harbour is a drowned river valley that formed area of about 50 km2 and a total catchment of 500 km2 during a rise in sea level approximately 10,000 years (Birch and McCready 2009). -

Obituary. Edward Pierson Ramsay

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Etheridge Jr, R., 1917. Obituary—Edward Pierson Ramsay, LL.D. Curator, 22nd September, 1874 to 31st December, 1894. Records of the Australian Museum 11(9): 205–217. [28 May 1917]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.11.1917.916 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia OBITUARY: EDWARD PIERSON RAMSAY, LI~.D. Curator, 22nd S'eptember, 1874 to 31st December, 1894. Dr. E. P. Ramsay was the third son of David Ramsay, M.D., the owner of the DobroYd Estate,Dobl'oyd POlnt,Long Cove. He was born at Dobroyd House on 3rd ,December ,1842, andwas,therefoi'e, in his 75th year at the time of his death. His ed ucation took place at St; Mark's Collegiate School, first at Darling Point and later at Macquarie Fields, presided over by tbeRev. G.F. Macarthur,who later became HeadMaster of The King's School, Parramatta. In 1863,. Mr. Ramsay matriculated at the University, and (in the same yeaI') also entered asa stud.ent of St. Paul's College. His name remained on the list of members of the University until December, 1865. In apportioni~lgthe Dobroyd Estate amqngstthe children 'of Dr. David. Ramsay, the large~nd beautiful garden was aUottedtothe subject oE this notice; arid cameilito his hands about the year 1867. He forthwith opened the Dobroyd New Plant and Seed . -

Ecology of Pyrmont Peninsula 1788 - 2008

Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Transformations: Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula 1788 - 2008 John Broadbent Sydney, 2010. Ecology of Pyrmont peninsula iii Executive summary City Council’s ‘Sustainable Sydney 2030’ initiative ‘is a vision for the sustainable development of the City for the next 20 years and beyond’. It has a largely anthropocentric basis, that is ‘viewing and interpreting everything in terms of human experience and values’(Macquarie Dictionary, 2005). The perspective taken here is that Council’s initiative, vital though it is, should be underpinned by an ecocentric ethic to succeed. This latter was defined by Aldo Leopold in 1949, 60 years ago, as ‘a philosophy that recognizes[sic] that the ecosphere, rather than any individual organism[notably humans] is the source and support of all life and as such advises a holistic and eco-centric approach to government, industry, and individual’(http://dictionary.babylon.com). Some relevant considerations are set out in Part 1: General Introduction. In this report, Pyrmont peninsula - that is the communities of Pyrmont and Ultimo – is considered as a microcosm of the City of Sydney, indeed of urban areas globally. An extensive series of early views of the peninsula are presented to help the reader better visualise this place as it was early in European settlement (Part 2: Early views of Pyrmont peninsula). The physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula has been transformed since European settlement, and Part 3: Physical geography of Pyrmont peninsula describes the geology, soils, topography, shoreline and drainage as they would most likely have appeared to the first Europeans to set foot there. -

A Biological Survey of the Murray Mallee South Australia

A BIOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE MURRAY MALLEE SOUTH AUSTRALIA Editors J. N. Foulkes J. S. Gillen Biological Survey and Research Section Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia 2000 The Biological Survey of the Murray Mallee, South Australia was carried out with the assistance of funds made available by the Commonwealth of Australia under the National Estate Grants Programs and the State Government of South Australia. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the Australian Heritage Commission or the State Government of South Australia. This report may be cited as: Foulkes, J. N. and Gillen, J. S. (Eds.) (2000). A Biological Survey of the Murray Mallee, South Australia (Biological Survey and Research, Department for Environment and Heritage and Geographic Analysis and Research Unit, Department for Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts). Copies of the report may be accessed in the library: Environment Australia Department for Human Services, Housing, GPO Box 636 or Environment and Planning Library CANBERRA ACT 2601 1st Floor, Roma Mitchell House 136 North Terrace, ADELAIDE SA 5000 EDITORS J. N. Foulkes and J. S. Gillen Biological Survey and Research Section, Heritage and Biodiversity Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001 AUTHORS D. M. Armstrong, J. N. Foulkes, Biological Survey and Research Section, Heritage and Biodiversity Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047 ADELAIDE SA 5001. S. Carruthers, F. Smith, S. Kinnear, Geographic Analysis and Research Unit, Planning SA, Department for Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, GPO Box 1815, ADELAIDE SA 5001. -

![No.[Number] 67 1919. July 1. to 1920. Sep[Tember] 30 [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6874/no-number-67-1919-july-1-to-1920-sep-tember-30-1-2006874.webp)

No.[Number] 67 1919. July 1. to 1920. Sep[Tember] 30 [1]

AMS587_64 – Edgar Waite Diary 67 – July 1919 to Sept 1920 This is a formatted version of the transcript file from the Atlas of Living Australia http://volunteer.ala.org.au/project/index/2204841 Page numbers at the bottom of this document do not correspond to the notebook page numbers. Parentheses are used when they are part of the original document and square brackets are used for insertions by the transcriber Text in square brackets may indicate the following: - Misspellings, with the correct spelling in square brackets preceded by an asterisk rendersveu*[rendezvous] - Tags for types of content [newspaper cutting] - Spelled out abbreviations or short form words F[ield[. Nat[uralists] - Words that cannot be transcribed [?] No.[Number] 67 1919. July 1. to 1920. Sep[tember] 30 [1] July. 1. Tues[day] Commencing this month as a convalescent from Sciatica. Locomotion is difficult &[and] slow. Wrote to Melbourne in reply, as to designation of Sardines &[and] pilchards, commercially. (Trades &[and] Customs Dep[artmen]t) 2. Wed[nesday] Received request from Narracoorte*[Naracoorte], through the Agric[ulture] Dep[artmen]t, to lecture at some future date. Com- mittee meeting. 3. Thurs[day] Reported on contents of a tin of Sardines marked [2] "Outing Brand" packed at Stockton Spring, Maine U.S.A. Determined them a Sardina pseudohispanica. (Amblygaster). Paid £1.4.<9>6 for making pattern of new piston. (A.W.Tremewen) 4 Fri[day] Prepared list of genera in fishes, proposed by me for Jordan's "Genera of Fishes. Attended (Presided) meet Aquarium Soc[iety] 5. Sat[urday] Wrote to Jordan and enclosed list of genera 7 Mon[day] Sent pocket wallet to Watson made by Miss Leicester for the purpose- [3] 8 Tues[day] "Children's Hour" for June contains my notes on the Big Whale. -

2016. a Cultural Cacophony: Museum Perspectives and Projects

A CulturalCacophony Museum Perspectives&Projects Identity Communication Culture Crisis Andrew Simpson Gina Hammond Editors: We ask that you please consider the environment before printing any part of this publication. Thank you TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ Error! Bookmark not defined. A professional cacophony ................................................................................................................... 3 Andrew Simpson and Gina Hammond ........................................................................................ 3 PERSPECTIVES ....................................................................................................................................... 14 Sowing the seeds of wisdom and cultivating thinking in museums ................................................. 15 Janelle Hatherly ......................................................................................................................... 15 The challenge of contemporary relevance in a digital era ................................................................ 28 Kim Williams ............................................................................................................................. 28 Museums and freedom of speech ................................................................................................... -

Neotype Designation for the Australian Pig-Footed Bandicoot Chaeropus Ecaudatus Ogilby, 1838

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343292739 Neotype designation for the Australian Pig-footed Bandicoot Chaeropus ecaudatus Ogilby, 1838 Article · July 2020 DOI: 10.3853/j.2201-4349.72.2020.1761 CITATIONS READS 0 8 3 authors, including: Kenny Travouillon Harry Parnaby Western Australian Museum Australian Museum 58 PUBLICATIONS 726 CITATIONS 35 PUBLICATIONS 414 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Fossil peramelemorphians View project Revising the Perameles bougainville complex and Chaeropus ecaudatus View project All content following this page was uploaded by Harry Parnaby on 30 July 2020. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Records of the Australian Museum (2020) Records of the Australian Museum vol. 72, issue no. 3, pp. 77–80 a peer-reviewed open-access journal https://doi.org/10.3853/j.2201-4349.72.2020.1761 published by the Australian Museum, Sydney communicating knowledge derived from our collections ISSN 0067-1975 (print), 2201-4349 (online) Neotype Designation for the Australian Pig-footed Bandicoot Chaeropus ecaudatus Ogilby, 1838 Kenny J. Travouillon1 , Harry Parnaby2 and Sandy Ingleby2 1 Western Australian Museum, Locked Bag 49, Welshpool DC WA 6986, Australia 2 Australian Museum Research Institute, Australian Museum, 1 William Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia Abstract. The original description of the now extinct Australian Pig-footed Bandicoot Chaeropus ecaudatus Ogilby, 1838 was based on one specimen from which the tail was missing. Re-examination of the skull thought to be the holotype of C. ecaudatus, revealed that it was associated with a skeleton with caudal vertebrae, thereby negating its type status. -

VI Chapter 1

& VI Chapter 1. The Preparatory Years (1827-1864). James Barnet was a professional architect who became a long serving member of the New South Wales civil service and for that reason a study of his official career should begin with an examination of his professional training. His career from his arrival in New South Wales in 1854 until 1860 and his work as Acting Colonial Architect from 31 October 1862 until 31 December 1864 is also reviewed in this chapter. On 21 August 1860 a notice appeared in the New South Wales Government Gazette which announced the appointment of James Barnet to a position of clerk of works in the Office of the Colonial Architect. Who was this young man who had arrived in Sydney in December 1854 and who, since that date, seemed to have experienced some difficulty in settling into regular employment? The position of clerk of works carried an annual salary of MOO and offered security and prospects for advancement. A curious person might 1. Throughout this study the name James Barnet will be used. The entry in ADB 3 records his name as Barnet, James Johnstone, the name shown on both his and his wifes death certificates. In the numerous files examined Barnet almost invariably signed his name as James Barnet. There were many occasions when his name was incorrectly spelled as Barnett in official papers as well as the press. 2 wonder whether Barnet was qualified to fill such a position or whether he had been appointed solely as the result of the patronage 2 of influential friends. -

Heritage Collection

H ERITAGEC OLLECTION N ELSON M EERS F OUNDATION 2005 STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES H ERITAGEC OLLECTION N ELSON M EERS F OUNDATION 2005 STATE LIBRARY OF NEW SOUTH WALES www.sl.nsw.gov.au/heritage/ Foreword State Library of New South Wales The Nelson Meers Foundation Heritage Collection following their liberation in 1945, reminds us Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 opened in 2003, with the aim of displaying of the horrors of that period of European history Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 a selection of the State Library’s finest items. and of the constant humanitarianism that works TTY (02) 9273 1541 These represent some of history’s greatest through our society. Australia’s craft traditions are Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au individual endeavours and highest intellectual represented in a beautiful display of silver items, achievements. For the following decade, the and we again return to the foundations and Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Heritage Collection will show an array of rare, development of the colony with displays of and selected public holidays famous and historically significant items from William Bradley’s charts and of materials relating Gallery space created by Jon Hawley the State Library’s world-renowned collections. to Governor Lachlan Macquarie. Project Manager: Phil Verner Coordinating Curator: Stephen Martin Public response over the last two years has been Curators and other experts will continue the Curators: Louise Anemaat, Ronald Briggs, Cheryl Evans, enthusiastic. Now, as we are entering the third popular series of events relating to the Heritage Mark Hildebrand, Warwick Hirst, Melissa Jackson, Richard Neville, year of the exhibition, this interest continues Collection. -

Blandowski, Krefft and the Aborigines on the Murray River Expedition

NATIVE COMPANIONS: BLANDOWSKI, KREFFT AND THE ABORIGINES ON THE MURRAY RIVER EXPEDITION HARRY ALLEN Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland, New Zealand. Honorary Associate in Archaeology, La Trobe University, Bundoora, VIC, Australia. ALLEN, H., 2009. Native companions: Blandowski, Krefft and the Aborigines on the Murray River expedi- tion. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 121(1): 129–145. ISSN 0035-9211. This paper explores relations between Blandowski, Krefft and the Aborigines during the 1856-57 Murray River expedition. As with many scientific enterprises in Australia, Aboriginal knowledge made a substantial contribution to the success of the expedition. While Blandowski generously acknowledged this, Krefft, who was responsible for the day to day running of the camp, maintained his distance from the Aborigines. The expedition context provides an insight into tensions between Blandowski and Krefft, and also into the complexities of the colonial project on the Murray River, which involved Aborigines, pasto- ralists, missionaries and scientists. Key words: scientific expedition, colonial attitudes, missionaries, contact history. WILLIAM BLANDOWSKI described the ‘Supersti- at an early stage of development. It remained a world tions, Customs and Burials of the Aborigines’ in an where Aboriginal communities continued to exist address to the Melbourne Mechanics’ Institute in and, to a limited extent, could live according to their October 1856. In that lecture, Blandowski warned own standards (Littleton et al. 2003). that ‘…the world was still without any distinct infor- Using the records of the expedition and contem- mation as to the habits and manners of the inhabit- porary accounts, this study will focus on Bland- ants of a country equal in size nearly to the whole of owski’s and Krefft’s actions and attitudes towards the Europe’ (The Argus, 25 October 1856).