The Language of the Veil

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Arabic Roots of Jazz and Blues

The Arabic Roots of Jazz and Blues ......Gunnar Lindgren........................................................... Black Africans of Arabic culture Long before the beginning of what we call black slavery, black Africans arrived in North America. There were black Africans among Columbus ’s crew on his first journey to the New World in 1492.Even the more militant of the earliest Spanish and Portuguese conquerors, such as Cortes and Pizarro, had black people by their side. In some cases, even the colonialist leaders themselves were black, Estebanico for example, who conducted an expedition to what is now Mexico, and Juan Valiente, who led the Spaniards when they conquered Chile. There were black colonialists among the first Spanish settlers in Hispaniola (today Haiti/Dominican Republic). Between 1502 and 1518, hundreds of blacks migrated to the New World, to work in the mines and for other reasons. It is interesting to note that not all of the black colonists of the first wave were bearers of African culture, but rather of Arabic culture. They were born and raised on the Iberian Peninsula (today Spain, Portugal, and Gibraltar) and had, over the course of generations, exchanged their original African culture for the Moorish (Arabic)culture. Spain had been under Arabic rule since the 8th century, and when the last stronghold of the Moors fell in 1492,the rulers of the reunified Spain – King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella – gave the go-ahead for the epoch-making voyages of Columbus. Long before, the Arabs had kept and traded Negro slaves. We can see them in old paintings, depicted in various settings of medieval European society. -

Arabic Music. It Began Something Like This : "The Arabs Are Very

ARAP.IC MUSIC \\y I. AURA WILLIAMS man's consideratinn of Ininian affairs, his chief cinestions are, IN^ "\Miat of the frture?" and "What of the past?" History helps him to answer lioth. Dissatisfied with history the searching mind asks again, "And Ijcfore that, what?" The records of the careful digging of archeologists reveal, that many of the customs and hahits of the ancients are not so different in their essence from ours of today. We know that in man's rise from complete savagery, in his first fumblings toward civilization there was an impulse toward beauty and toward an expression of it. We know too, that his earliest expression was to dance to his own instinctive rhythms. I ater he sang. Still later he made instruments to accompany his dancing and his singing. At first he made pictures of his dancing and his instruments. Later he wrote about the danc- ing and his instruments. Later he wrote about the dancing and sing- ing and the music. Men have uncovered many of his pictures and his writings. From the pictures we can see what the instruments were like. We can, perhaps, reconstruct them or similar ones and hear the (luality of sound which they supplied. But no deciphering of the writings has yet disclosed to rs what combinations or sequences of sounds were used, nor what accents marked his rhythms. While one man is digging in the earth to turn up what records he may find of man's life "before that," another is studying those races who today are living in similar primitive circumstances. -

Arabic Language and Literature 1979 - 2018

ARABIC LANGUAGEAND LITERATURE ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE 1979 - 2018 ARABIC LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE A Fleeting Glimpse In the name of Allah and praise be unto Him Peace and blessings be upon His Messenger May Allah have mercy on King Faisal He bequeathed a rich humane legacy A great global endeavor An everlasting development enterprise An enlightened guidance He believed that the Ummah advances with knowledge And blossoms by celebrating scholars By appreciating the efforts of achievers In the fields of science and humanities After his passing -May Allah have mercy on his soul- His sons sensed the grand mission They took it upon themselves to embrace the task 6 They established the King Faisal Foundation To serve science and humanity Prince Abdullah Al-Faisal announced The idea of King Faisal Prize They believed in the idea Blessed the move Work started off, serving Islam and Arabic Followed by science and medicine to serve humanity Decades of effort and achievement Getting close to miracles With devotion and dedicated The Prize has been awarded To hundreds of scholars From different parts of the world The Prize has highlighted their works Recognized their achievements Never looking at race or color Nationality or religion This year, here we are Celebrating the Prize›s fortieth anniversary The year of maturity and fulfillment Of an enterprise that has lived on for years Serving humanity, Islam, and Muslims May Allah have mercy on the soul of the leader Al-Faisal The peerless eternal inspirer May Allah save Salman the eminent leader Preserve home of Islam, beacon of guidance. -

Or C\^Iing Party. \

r 3 the season advances one's that they are their own excuse for being— This type is prettily developed In mole- the dismay of those observers who dislike thoughts turn toward evening en- as reconstructed emeralds and ruMes skin. Mrs. Frank Nelson, Jr., has a their fidgety movements and would fain scarf and big pillow muff of this fur enjoy the classic calm of the unbeplum- tertainments, and it is the toilette have gained a distinction of their own do soiree and de theatre that which she wears very becomingly. aged bandeau. manteau by their real beauty and excellence. There is also a scarf of tlie black One of the quaintest coiffure ornaments occupy the attention of the lady of fash- big Moreover, fur imitations are absolutely fur In Mr. Wells’ sketch. It is fitted in town is black velvet and ion. The evening gowns mentioned in lynx bright green if the sisters and I Indispensable wives, about the neck and at one end Is orna- tulle. It Is clasped in the back with a these pages from time to time and de- of something to give in celebration of Many families hold the bridal veil as one popular colors in what is known as tho daughters of others than multi-million- a of made in the mented with handsome sil£ frog, pro- narrow' hand of mother pearl, very scribed by pen pictures Christman has begun to crowd the shops. of the most precious of heirlooms, to b© “made*’ veils and these with their well aires are to be with ducing that “one-sided” effect at once thin and very lustrous. -

The Construction of National Culture and Identity in a Province: the Case of the People's House of Kayseri

THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY FULYA BALKAR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF MEDIA AND CULTURAL STUDIES DECEMBER 2019 i ii Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Yaşar Kondakçı Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Lütfi Doğan Tılıç (Başkent Uni., HIT) Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan (METU, ADM) Assoc. Prof. Barış Çakmur (METU, ADM) iii ii I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name: Fulya Balkar Signature : iii ABSTRACT THE CONSTRUCTION OF NATIONAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN A PROVINCE: THE CASE OF THE PEOPLE'S HOUSE OF KAYSERI Balkar, Fulya M.S., Department of Media and Cultural Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Necmi Erdoğan December 2019, 249 pages This thesis focuses on the Kayseri House experience in early republican period and aims to explore how the narratives of national culture and identity were constructed in a so-called conservative province in the context of the Kayseri House. -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

Religion in the Public Sphere

Religion in the Public Sphere Ars Disputandi Supplement Series Volume 5 edited by MAARTEN WISSE MARCEL SAROT MICHAEL SCOTT NIEK BRUNSVELD Ars Disputandi [http://www.ArsDisputandi.org] (2011) Religion in the Public Sphere Proceedings of the 2010 Conference of the European Society for Philosophy of Religion edited by NIEK BRUNSVELD & ROGER TRIGG Utrecht University & University of Oxford Utrecht: Ars Disputandi, 2011 Copyright © 2011 by Ars Disputandi, version: September 14, 2011 Published by Ars Disputandi: The Online Journal for Philosophy of Religion, [http://www.arsdisputandi.org], hosted by Igitur publishing, Utrecht University Library, The Netherlands [http://www.uu.nl/university/library/nl/igitur/]. Typeset in Constantia 9/12pt. ISBN: 978-90-6701-000-9 ISSN: 1566–5399 NUR: 705 Reproduction of this (or parts of this) publication is permitted for non-commercial use, provided that appropriate reference is made to the author and the origin of the material. Commercial reproduction of (parts of) it is only permitted after prior permission by the publisher. Contents Introduction 1 ROGER TRIGG 1 Does Forgiveness Violate Justice? 9 NICHOLAS WOLTERSTORFF Section I: Religion and Law 2 Religion and the Legal Sphere 33 MICHAEL MOXTER 3 Religion and Law: Response to Michael Moxter 57 STEPHEN R.L. CLARK Section II: Blasphemy and Offence 4 On Blasphemy: An Analysis 75 HENK VROOM 5 Blasphemy, Offence, and Hate Speech: Response to Henk Vroom 95 ODDBJØRN LEIRVIK Section III: Religious Freedom 6 Freedom of Religion 109 ROGER TRIGG 7 Freedom of Religion as the Foundation of Freedom and as the Basis of Human Rights: Response to Roger Trigg 125 ELISABETH GRÄB-SCHMIDT Section IV: Multiculturalism and Pluralism in Secular Society 8 Multiculturalism and Pluralism in Secular Society: Individual or Collective Rights? 147 ANNE SOFIE ROALD 9 After Multiculturalism: Response to Anne Sofie Roald 165 THEO W.A. -

Mpub10110094.Pdf

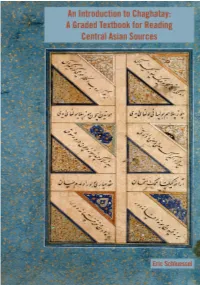

An Introduction to Chaghatay: A Graded Textbook for Reading Central Asian Sources Eric Schluessel Copyright © 2018 by Eric Schluessel Some rights reserved This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, California, 94042, USA. Published in the United States of America by Michigan Publishing Manufactured in the United States of America DOI: 10.3998/mpub.10110094 ISBN 978-1-60785-495-1 (paper) ISBN 978-1-60785-496-8 (e-book) An imprint of Michigan Publishing, Maize Books serves the publishing needs of the University of Michigan community by making high-quality scholarship widely available in print and online. It represents a new model for authors seeking to share their work within and beyond the academy, offering streamlined selection, production, and distribution processes. Maize Books is intended as a complement to more formal modes of publication in a wide range of disciplinary areas. http://www.maizebooks.org Cover Illustration: "Islamic Calligraphy in the Nasta`liq style." (Credit: Wellcome Collection, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/chengwfg/, licensed under CC BY 4.0) Contents Acknowledgments v Introduction vi How to Read the Alphabet xi 1 Basic Word Order and Copular Sentences 1 2 Existence 6 3 Plural, Palatal Harmony, and Case Endings 12 4 People and Questions 20 5 The Present-Future Tense 27 6 Possessive -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

Andalusian Roots and Abbasid Homage in the Qubbat Al-Barudiyyin 133

andalusian roots and abbasid homage in the qubbat al-barudiyyin 133 YASSER TABBAA ANDALUSIAN ROOTS AND ABBASID HOMAGE IN THE QUBBAT AL-BARUDIYYIN IN MARRAKECH Without any question, I was attracted to the fi eld of Andalusian artisans are known to have resettled in Islamic architecture and archaeology through Oleg Morocco—it seems anachronistic in dealing with peri- Grabar’s famous article on the Dome of the Rock, ods when Andalusia itself was ruled by dynasties from which I fi rst read in 1972 in Riyadh, while contemplat- Morocco, in particular the Almoravids (1061–1147) ing what to do with the rest of my life.1 More specifi cally and the Almohads (1130–1260). More specifi cally, to the article made me think about domes as the ultimate view Almoravid architecture from an exclusively Cor- aesthetic statements of many architectural traditions doban perspective goes counter to the political and and as repositories of iconography and cosmology, cultural associations of the Almoravids, who, in addi- concepts that both Grabar and I have explored in different ways in the past few decades. This article, on a small and fragile dome in Marrakech, continues the conversation I began with Oleg long before he knew who I was. The Qubbat al-Barudiyyin in Marrakech is an enig- matic and little-studied monument that stands at the juncture of historical, cultural, and architectural trans- formations (fi g. 1). Although often illustrated, and even featured on the dust jacket of an important sur- vey of Islamic architecture,2 this monument is in fact very little known to the English-speaking scholarly world, a situation that refl ects its relatively recent dis- covery and its location in a country long infl uenced by French culture. -

An Embellishment: Purdah

An Embellishment: Purdah For An Embellishment: Purdah,i a two-part text installation for an exhibition, Spatial Imagination (2006), I selected twelve short extracts from ‘To Miss the Desert’ and rewrote them as ‘scenes’ of equal length, laid out in the catalogue as a grid, three squares wide by four high, to match the twelve panes of glass in the west-facing window of the gallery looking onto the street. Here, across the glass, I repeatedly wrote the word ‘purdah’ in black kohl in the script of Afghanistan’s official languages – Dari and Pashto.ii The term purdah means curtain in Persian and describes the cultural practice of separating and hiding women through clothing and architecture – veils, screens and walls – from the public male gaze. The fabric veil has been compared to its architectural equivalent – the mashrabiyya – an ornate wooden screen and feature of traditional North African domestic architecture, which also ‘demarcates the line between public and private space’.iii The origins of purdah, culturally, religiously and geographically, are highly debated,iv and connected to class as well as gender.v The current manifestation of this gendered spatial practice varies according to location and involves covering different combinations of hair, face, eyes and body. In Afghanistan, for example, under the Taliban, when in public, women were required to wear what has been termed a burqa, a word of Pakistani origin. In Afghanistan the full-length veil is more commonly known as the chadoree or chadari, a variation of the Persian chador, meaning tent.vi This loose garment, usually sky-blue, covers the body from head to foot. -

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & the Exuberance of Mamluk Design

The Aesthetics of Islamic Architecture & The Exuberance of Mamluk Design Tarek A. El-Akkad Dipòsit Legal: B. 17657-2013 ADVERTIMENT. La consulta d’aquesta tesi queda condicionada a l’acceptació de les següents condicions d'ús: La difusió d’aquesta tesi per mitjà del servei TDX (www.tesisenxarxa.net) ha estat autoritzada pels titulars dels drets de propietat intel·lectual únicament per a usos privats emmarcats en activitats d’investigació i docència. No s’autoritza la seva reproducció amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva difusió i posada a disposició des d’un lloc aliè al servei TDX. No s’autoritza la presentació del s eu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant al resum de presentació de la tesi com als seus continguts. En la utilització o cita de parts de la tesi és obligat indicar el nom de la persona autora. ADVERTENCIA. La consulta de esta tesis queda condicionada a la aceptación de las siguientes condiciones de uso: La difusión de esta tesis por medio del servicio TDR (www.tesisenred.net) ha sido autorizada por los titulares de los derechos de propiedad intelectual únicamente para usos privados enmarcados en actividades de investigación y docencia. No se autoriza su reproducción con finalidades de lucro ni su difusión y puesta a disposición desde un sitio ajeno al servicio TDR. No se autoriza la presentación de su contenido en una ventana o marco ajeno a TDR (framing). Esta reserva de derechos afecta tanto al resumen de presentación de la tesis como a sus contenidos.