Foreign Ownersidp of Airlines and Korean Carriers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COM(79)311 Final Brussels / 6Th July 1979

ARCHIVES HISTORIQUES DE LA COMMISSION COLLECTION RELIEE DES DOCUMENTS "COM" COM (79) 311 Vol. 1979/0118 Disclaimer Conformément au règlement (CEE, Euratom) n° 354/83 du Conseil du 1er février 1983 concernant l'ouverture au public des archives historiques de la Communauté économique européenne et de la Communauté européenne de l'énergie atomique (JO L 43 du 15.2.1983, p. 1), tel que modifié par le règlement (CE, Euratom) n° 1700/2003 du 22 septembre 2003 (JO L 243 du 27.9.2003, p. 1), ce dossier est ouvert au public. Le cas échéant, les documents classifiés présents dans ce dossier ont été déclassifiés conformément à l'article 5 dudit règlement. In accordance with Council Regulation (EEC, Euratom) No 354/83 of 1 February 1983 concerning the opening to the public of the historical archives of the European Economic Community and the European Atomic Energy Community (OJ L 43, 15.2.1983, p. 1), as amended by Regulation (EC, Euratom) No 1700/2003 of 22 September 2003 (OJ L 243, 27.9.2003, p. 1), this file is open to the public. Where necessary, classified documents in this file have been declassified in conformity with Article 5 of the aforementioned regulation. In Übereinstimmung mit der Verordnung (EWG, Euratom) Nr. 354/83 des Rates vom 1. Februar 1983 über die Freigabe der historischen Archive der Europäischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft und der Europäischen Atomgemeinschaft (ABI. L 43 vom 15.2.1983, S. 1), geändert durch die Verordnung (EG, Euratom) Nr. 1700/2003 vom 22. September 2003 (ABI. L 243 vom 27.9.2003, S. -

Navaero Achieves First European EASA Approved STC on T Bag™C2

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Lars Eriksson navAero, Ab +46-60-66-4100 [email protected] navAero Achieves First European EASA Approved STC on txBag™C22 EFB for B737-NG and Classic Series with SAS 04 MARCH, 2008 Sundsvall, Sweden — navAero has received Supplemental Type Certification (STC) for the txBagC22 EFB System from EASA as an approved change in the type design on the B737-300/400/500/600/700/800/900 Series aircraft. Executed on behalf of navAero by Saab Aerotech,Aircraft Services in cooperation with SAS Scandinavian Airlines, this marks the first EASA Approved STC for the txBagC22 System as an EFB and marks yet another certification achieved by navAero. The STC EASA.A.S.03259 for the B737-NG and Classic Series aircraft was issued on February 22, 2008 by the European Aviation Safety Agency. The installation was executed as a part of the NUP II+ Project VDLM4 and CPDLC Operational trials at Stockholm-Arlanda. navAero spokesperson and Chief Operating Officer, Lars Eriksson, stated “We are tremendously excited about this landmark event of achieving the very first EASA approval for the txBagC22 EFB System. With this certification, the navAero txBag C22 computer and display technology can provide airlines flying one of the worlds most popular and widely deployed aircraft series that are operating under EASA regulations, the ability to install a truly affordable, rugged hardware platform suitable for running the most demanding and advanced aviation software applications. This STC now gives commercial airlines operating B737 Classics and NG’s throughout Europe and elsewhere in the world, the ability to deploy our hardware technology…a platform that can help them improve their operational efficiency and increase situational awareness. -

Fields Listed in Part I. Group (8)

Chile Group (1) All fields listed in part I. Group (2) 28. Recognized Medical Specializations (including, but not limited to: Anesthesiology, AUdiology, Cardiography, Cardiology, Dermatology, Embryology, Epidemiology, Forensic Medicine, Gastroenterology, Hematology, Immunology, Internal Medicine, Neurological Surgery, Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oncology, Ophthalmology, Orthopedic Surgery, Otolaryngology, Pathology, Pediatrics, Pharmacology and Pharmaceutics, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, Physiology, Plastic Surgery, Preventive Medicine, Proctology, Psychiatry and Neurology, Radiology, Speech Pathology, Sports Medicine, Surgery, Thoracic Surgery, Toxicology, Urology and Virology) 2C. Veterinary Medicine 2D. Emergency Medicine 2E. Nuclear Medicine 2F. Geriatrics 2G. Nursing (including, but not limited to registered nurses, practical nurses, physician's receptionists and medical records clerks) 21. Dentistry 2M. Medical Cybernetics 2N. All Therapies, Prosthetics and Healing (except Medicine, Osteopathy or Osteopathic Medicine, Nursing, Dentistry, Chiropractic and Optometry) 20. Medical Statistics and Documentation 2P. Cancer Research 20. Medical Photography 2R. Environmental Health Group (3) All fields listed in part I. Group (4) All fields listed in part I. Group (5) All fields listed in part I. Group (6) 6A. Sociology (except Economics and including Criminology) 68. Psychology (including, but not limited to Child Psychology, Psychometrics and Psychobiology) 6C. History (including Art History) 60. Philosophy (including Humanities) -

Sea King Salute P16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley Looks at the Operational History of the Westland Sea King in UK Military Service

UK SEA KING SALUTE NEWS N N IO IO AT NEWS VI THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF FLIGHT Incorporating A AVIATION UK £4.50 FEBRUARY 2016 www.aviation-news.co.uk Low-cost NORWEGIAN Scandinavian Style AMBITIONS EXCLUSIVE FIREFIGHTING A-7 CORSAIR II BAe 146s & RJ85s LTV’s Bomb Truck Next-gen Airtankers SUKHOI SUPERJET Russia’s Rising Star 01_AN_FEB_16_UK.indd 1 05/01/2016 12:29 CONTENTS p20 FEATURES p11 REGULARS 20 Spain’s Multi-role Boeing 707s 04 Headlines Rodrigo Rodríguez Costa details the career of the Spanish Air Force’s Boeing 707s which have served 06 Civil News the country’s armed forces since the late 1980s. 11 Military News 26 BAe 146 & RJ85 Airtankers In North America and Australia, converted BAe 146 16 Preservation News and RJ85 airliners are being given a new lease of life working as airtankers – Frédéric Marsaly explains. 40 Flight Bag 32 Sea King Salute p16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley looks at the operational history of the Westland Sea King in UK military service. 68 Airport Movements 42 Sukhoi Superjet – Russia’s 71 Air Base Movements Rising Star Aviation News Assistant Editor James Ronayne 74 Register Review pro les the Russian regional jet with global ambitions. 48 A-7 Corsair II – LTV’s Bomb Truck p74 A veteran of both the Vietnam con ict and the rst Gulf War, the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7 Corsair II packed a punch, as Patrick Boniface describes. 58 Norwegian Ambitions Aviation News Editor Dino Carrara examines the rapid expansion of low-cost carrier Norwegian and its growing long-haul network. -

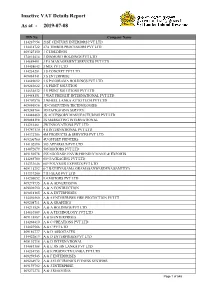

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08

Inactive VAT Details Report As at - 2019-07-08 TIN No Company Name 114287954 21ST CENTURY INTERIORS PVT LTD 114418722 27A TIMBER PROCESSORS PVT LTD 409327150 3 C HOLDINGS 174814414 3 DIAMOND HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114689491 3 FA MANAGEMENT SERVICES PVT LTD 114458643 3 MIX PVT LTD 114234281 3 S CONCEPT PVT LTD 409084141 3 S ENTERPRISE 114689092 3 S PANORAMA HOLDINGS PVT LTD 409243622 3 S PRINT SOLUTION 114634832 3 S PRINT SOLUTIONS PVT LTD 114488151 3 WAY FREIGHT INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114707570 3 WHEEL LANKA AUTO TECH PVT LTD 409086896 3D COMPUTING TECHNOLOGIES 409248764 3D PACKAGING SERVICE 114448460 3S ACCESSORY MANUFACTURING PVT LTD 409088198 3S MARKETING INTERNATIONAL 114251461 3W INNOVATIONS PVT LTD 114747130 4 S INTERNATIONAL PVT LTD 114372706 4M PRODUCTS & SERVICES PVT LTD 409206760 4U OFFSET PRINTERS 114102890 505 APPAREL'S PVT LTD 114072079 505 MOTORS PVT LTD 409150578 555 EGODAGE ENVIR;FRENDLY MANU;& EXPORTS 114265780 609 PACKAGING PVT LTD 114333646 609 POLYMER EXPORTS PVT LTD 409115292 6-7 BATHIYAGAMA GRAMASANWARDENA SAMITIYA 114337200 7TH GEAR PVT LTD 114205052 9.4.MOTORS PVT LTD 409274935 A & A ADVERTISING 409096590 A & A CONTRUCTION 409018165 A & A ENTERPRISES 114456560 A & A ENTERPRISES FIRE PROTECTION PVT LT 409208711 A & A GRAPHICS 114211524 A & A HOLDINGS PVT LTD 114610569 A & A TECHNOLOGY PVT LTD 409118887 A & B ENTERPRISES 114268410 A & C CREATIONS PVT LTD 114023566 A & C PVT LTD 409186777 A & D ASSOCIATES 114422819 A & D ENTERPRISES PVT LTD 409192718 A & D INTERNATIONAL 114081388 A & E JIN JIN LANKA PVT LTD 114234753 A & -

2016:04 Uncertainty Assessment of the SCANAIR V 7 5 Computer Program in Analyses of BWR Reactivity Initiated Accidents

Author: Lars Olof Jernkvist Research 2016:04 Uncertainty assessment of the SCANAIR V_7_5 computer program in analyses of BWR reactivity initiated accidents Report number: 2016:04 ISSN: 2000-0456 Available at www.stralsakerhetsmyndigheten.se SSM 2016:04 SSM:s perspektiv Bakgrund Beräkningsprogrammet SCANAIR har utvecklats av IRSN (Institut de Radio- protection et de Sûreté Nucléaire) för att analysera reaktivitetshändelser (RIA) i lättvattenreaktorer. I utbyte mot årliga bidrag till utvecklingen av SCANAIR har SSM tillgång till beräkningsprogrammet och kan utföra egna analyser av bränslebeteende under reaktivitetshändelser. Arbetet utförs av Quantum Technologies AB, vilka utvecklar och administrerar beräkning- sprogrammet på SSM:s uppdrag. SSM:s utveckling av SCANAIR är främst inriktad mot de termohydrauliska modellerna, i syfte att förbättra analysmöjligheterna i kokvattenreaktorer. I ett tidigare arbete har en modell för tvåfasströmning utvecklats vilken tagits in av IRSN i SCANAIR V_7_5. Föreliggande arbete är 2015 års bidrag till SCANAIR-utvecklingen och är en osäkerhets- och känslighetsstudie av grundläggande parametrar som beräknas av programmet. Studien är baserad på ett japanskt pulsreaktorexperiment, FK-1, där en förbestrålad bränslestav av typisk kokvattenreaktordesign utsätts för en reaktivitets- transient Resultat Osäkerhets- och känslighetsstudien är utförd enligt en metodik som används i en pågående benchmark mellan flera instituts beräkningsprogram för RIA-analyser inom OECD/NEA. Föreliggande arbete visar på god över- ensstämmelse mellan resultat erhållna med SCANAIR V_7_5 och testet FK-1. Temperaturmaximum i bränsle och kapsling såsom den beräknas stämmer väl överens med experimentella data. I modelleringen av det senare förlop- pet, dvs. avklingningen av temperatur i bränslet genom värmeöverföring till det omgivande vattnet, finns betydligt större osäkerheter. -

CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2H CHANGE FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION CHG 2 Air Traffic Organization Policy Effective Date: November 8, 2018 SUBJ: Contractions 1. Purpose of This Change. This change transmits revised pages to Federal Aviation Administration Order JO 7340.2H, Contractions. 2. Audience. This change applies to all Air Traffic Organization (ATO) personnel and anyone using ATO directives. 3. Where Can I Find This Change? This change is available on the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications and https://employees.faa.gov/tools_resources/orders_notices. 4. Distribution. This change is available online and will be distributed electronically to all offices that subscribe to receive email notification/access to it through the FAA website at http://faa.gov/air_traffic/publications. 5. Disposition of Transmittal. Retain this transmittal until superseded by a new basic order. 6. Page Control Chart. See the page control chart attachment. Original Signed By: Sharon Kurywchak Sharon Kurywchak Acting Director, Air Traffic Procedures Mission Support Services Air Traffic Organization Date: October 19, 2018 Distribution: Electronic Initiated By: AJV-0 Vice President, Mission Support Services 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 PAGE CONTROL CHART Change 2 REMOVE PAGES DATED INSERT PAGES DATED CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−38............ 7/19/18 CAM 1−1 through CAM 1−18........... 11/8/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1................... 7/19/18 3−1−1 through 3−4−1.................. 11/8/18 Page Control Chart i 11/8/18 JO 7340.2H CHG 2 CHANGES, ADDITIONS, AND MODIFICATIONS Chapter 3. ICAO AIRCRAFT COMPANY/TELEPHONY/THREE-LETTER DESIGNATOR AND U.S. -

Chris Brady's Non-British Safety Card Collection Available for Trade For

Chris Brady's Non-British Safety Card Collection List date: 19/05/2021 Available for trade for British Cards Total 2257 cards Aircraft type Code or description Year (un-named operator) 12 cards B 707 Nov 82 S.P.E.product 1982 BAe 111 200 B & W Beech 23, 24, 76 BO 105 11"x7.5" B&W laminated DC 6B N37571 DHC 6 6"x12" DHC 6 300 EC 155 25210 ©2005 Safeair Inc G-73 Mallard P180 Avanti REF.PGO-107-5-2-93 (CSI) 1993 PA 31 350 Navajo Typed on A4 paper S 76 Spirit CSI 1984 bifold 6.5"x11" 1984 (un-named operator) Canadien 1 cards BAe 748 Bifold card Typo-Press Timmins (un-named operator) German 1 cards GA Commander 862025-517F (10x17cm B&W card) Adria 2 cards CRJ DC 9 82 A4 Adria Airways 2 cards BAe 111 500 DC 9 30/50 bifold 1988 AeBal 1 cards DC 9 / B717 Bifold Aegean Airlines 1 cards Page 1 of 108 Aircraft type Code or description Year BAe 146 /RJ100 "Avro RJ 100" Aero Arctic Helicopter 3 cards Bell 204 REF B24-47-2-7-89 (CSI) 1989 Bell 206 JetRanger REF.206-47-11-7-89 (CSI) 1989 Bell 206L LongRanger REF. 26L-47-8-7-89 (CSI) 1989 Aero California 1 cards DC 9 10 Orig. 2/02 2002 Aero Continente s.a. 1 cards B 727 100 trifold 1999 Aero Lyon 1 cards DC 10 30 AEY-DOC-011 2001 Aero Peru 1 cards B 727 100 1.06.29.073.00/UG PL-CL 1999 Aero Virgin Islands 1 cards DC 3 Aeroflot 23 cards A 320 Valid from 17.01.2020 2020 A 330 Valid from 01.07.2016 2016 AN 2 tall vintage paper folder AN 24B tall vintage paper folder IL 62 A4 plastic red borders IL 62 white "3AO NPP" IL 86 6.5"x10" white IL 86 7"x11" white 2003 IL 86 A4 red & white IL 96 300 Skyteam 2003 -

Flygteknikerns Värld Medlemstidning För Svensk Flygteknikerförening, SFF

Nr 1 2013 Flygteknikerns Värld Medlemstidning för Svensk Flygteknikerförening, SFF AEI Kongressrapport Flygteknikerns dag B787 typkurs We keep them flying ... ...Safely Redaktören har ordet HENRIK ZAAR [email protected] sedan kom hem berättade han omständligt Tiden går fort när man har roligt... men i för mamma att på pappas jobb fanns det Flygteknikerns Värld vår bransch är det just nu inte speciellt kul, minnsan en jättefin och stor traktor, mam- vi nås precis av beskeden att SAS kommer man frågade då om det inte fanns nåt annat att behöva göra besparingar på mycket stora fint, varpå sonen som inte pratade riktigt Medlemstidning för Svensk Flygtekniker- belopp. Vad detta innebär för våra kollegor rent, tänker en stund och säger sedan med förening, SFF. Utkommer med fyra nummer går just nu inte att överblicka. Ola kommer eftertyck på skånska ”FYFAN”.... Han vet per år. att berätta mer om detta i sina artiklar. inte hur rätt han har när det gäller Avros... ANSVARIG UTGIVARE När jag skriver denna ledare så sitter jag Vad ska nu detta nummer handla om då? Ola Blomqvist faktiskt på tåget mot Linköping, tåg är skramligt och obekvämt men det enda kol- Skolan i Nyköping bland annat, flygtek- REDAKTÖR lektiva transportmedlet från mina nuvarande nikerns dag förstås, AEI kongressen, lite Henrik Zaar hemtrakter till mina gamla hemtrakter (om Boeing 787 samt en hel del SAS. man nu inte vill vara fakir och åka buss). REDAKTIONEN Resan upp tar 3 timmar och vad kan man då Flygteknikerns Värld roa sig med. Jag skriver och den 4 årige so- c/o Henrik Zaar nen som sitter i sätet bredvid mig och tittar // Henrik Zaar Hjularöd Holstermöllan på film. -

AVIATIONTRENDS Statistics, Analysis and Information from the Swedish Transport Agency 2012 2 AVIATION TRENDS 2012

AVIATIONTRENDS STATISTICS, ANALYSIS AND INFORMATION FROM THE SWEDISH TRANSPORT AGENCY 2012 2 AVIATION TRENDS 2012 Aviation Trends 2012 is published by the Swedish Transport Agency (Transportstyrelsen) For further information, please contact Daniel Hellström, head of Statistics and market oversight section, Civil Aviation Department, [email protected] Transportstyrelsen, SE-601 73 Norrköping, Sweden | www.transportstyrelsen.se Translations reviewed by Helena Kjellström, Swedish Transport Agency Photo: © Copyright Etsabild AB / Malcolm Hanes s 1 | Jacob Sjöman s 4, 6, 13, 17, 19, 22, 23 | SAS s 8, 9 | Transair Sweden s 10 | Göran Billeson s 14 | Asif Akbar s 29 AVATION TRENDS 2012 3 FOREWORD We have the pleasure of publishing Aviation Trends 2012. This magazine is published by the Swedish Transport Agency (Transportstyrelsen) and it is published in English for our international readers. The articles in Aviation Trends 2012 are selected from the Swedish magazine Flygtendenser and range from the beginning of Swedish aviation 100 years ago to present 7 15 challenges with development of risk based systems for oversight of civil aviation. The magazine also covers some facts about the Civil Aviation Department as well as flight safety and passenger statistics for 2011, all this to give the reader some information about the Swedish aviation market. The long-term safety goal for all transport modes in Sweden is that no one should be killed or seriously 25 injured as a result of an accident. Sweden has a good aviation safety record, the international cooperation within ICAO, Euro control, EU and EASA has significantly contributed to this positive development by agreeing on CONTENT common safety standards. -

Flygteknikerns Värld Medlemstidning För Svensk Flygteknikerförening, SFF Innehåll FTV Nr 2-3 2011 Redaktören Har Ordet

Nr 2-3 2011 Flygteknikerns Värld Medlemstidning för Svensk Flygteknikerförening, SFF Innehåll FTV nr 2-3 2011 Redaktören har ordet..................................3 Ordförande har ordet...............................4-5 Flygteknikerns status del 2.........................6 Skolbesök...................................................7 Lokalavdelningar...................................8-15 TYA..........................................................16 Le Caravelle Club.....................................17 747 kurs CPH......................................18-19 SFF & SRAT informerar.....................20-23 Flygteknikerns Värld Medlemstidning för Svensk Flygtekniker- förening, SFF. Utkommer med fyra nummer per år. ANSVARIG UTGIVARE Ola Blomqvist REDAKTÖR Jan Ivarsson REDAKTIONEN Flygteknikerns Värld c/o Jan Ivarsson Ringvägen 11 C 118 23 Stockholm 08-644 14 71 0707-606492 [email protected] OMSLAGSBILDER Framsida: 737 NG foto: Stefan Lindgren Baksida: Pitts in action foto: Henrik Zaar TRYCKERI Trydells tryckeri AB Industrigatan 8 Box 68 312 21 Laholm Annonsering är kostnadsfri för SFFs medlemmar. Redaktionen förbehåller sig rätten att redigera inkomna bidrag. Åsikter och synpunkter framförda i signerade artiklar behöver nödvändigtvis inte vara SFFs officiella. 2 Flygteknikerns Värld nr 2-3 • 2011 Redaktören JAN IVARSSON har ordet [email protected] Då ramlade sommaren över fackligt denna vår. Branchen vingar. Där kan ni logga in och som redaktör. Fortsätt att mata en igen med samma slagkraft verkar stabilisera sig och aktörer hitta mycket information om in bara så kan vi få till ett minst som vintern gör när den kom- blommar upp och upphandlar vad som händer i det fackliga lika bra vinternummer. Deadline mer på hösten. Man blir lika på både gott och ont. Den enes samt att ni uppdatera era egna för det är den 23 november. Så fascinerad som alltid hur allt bröd den andres död har väl till uppgifter. -

Flotte Air France

Plane e-List Civil Aircraft Register by Airfleets Sweden Issue September, 1st, 2010 http://www.airfleets.net Notice This document contains the list of all aircraft registered in the country supported by this document. Planes are grouped by active and inactive status, then sorted by registration in alphabetic order. Note that the following aircraft types are listed in this document. - Airbus A300 - Airbus A310 - Airbus A318 - Airbus A319 - Airbus A320 - Airbus A321 - Airbus A330 - Airbus A340 - Airbus A380 - ATR 42/72 - BAe 146 / Avro RJ - Boeing 717 - Boeing 737 - Boeing 737 Next Gen - Boeing 747 - Boeing 757 - Boeing 767 - Boeing 777 - Boeing 787 - Canadair Regional Jet - Concorde - Dash 8 - Embraer 120 Brasilia - Embraer 135/145 - Embraer 170/175 - Embraer 190/195 - Fokker 50 - Fokker 70/100 - Lockheed L-1011 TriStar - McDonnell Douglas DC-10 - McDonnell Douglas MD-11 - McDonnell Douglas MD-80/90 - Saab 2000 - Saab 340 - Sukhoi SuperJet 100 The author reserves the right not to be responsible for the topicality, correctness, completeness or quality of the information provided. Liability claims regarding damage caused by the use of any information provided, including any kind of information which is incomplete or incorrect,will therefore be rejected. No part of this letter or information contained in it may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means. Abbreviations used MSN : Manufactured Serial Number Reg : Registration Man. Year : Manufactured Year Ex : Last 5 previous registrations For more information about aircraft listed in this document, go to http://www.airfleets.net This document is not an offical register. Contents Active aircraft .