University of Birmingham Managing a Megacity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urban Governance and Turning African Ciɵes Around: Lagos Case Study

Advancing research excellence for governance and public policy in Africa PASGR Working Paper 019 Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study Agunbiade, Elijah Muyiwa University of Lagos, Nigeria Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji University of Lagos, Nigeria August, 2016 This report was produced in the context of a mul‐country study on the ‘Urban Governance and Turning African Cies Around ’, generously supported by the UK Department for Internaonal Development (DFID) through the Partnership for African Social and Governance Research (PASGR). The views herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those held by PASGR or DFID. Author contact informaƟon: Elijah Muyiwa Agunbiade University of Lagos, Nigeria [email protected] or [email protected] Suggested citaƟon: Agunbiade, E. M. and Olajide, O. A. (2016). Urban Governance and Turning African CiƟes Around: Lagos Case Study. Partnership for African Social and Governance Research Working Paper No. 019, Nairobi, Kenya. ©Partnership for African Social & Governance Research, 2016 Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] www.pasgr.org ISBN 978‐9966‐087‐15‐7 Table of Contents List of Figures ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ........................................................................................................................ iii Acronyms ............................................................................................................................ -

LSETF NEWSLETTER MARCH-2 Copy

MEET TEJU ABISOYE, OUR ACTING EXECUTIVE SECRETARY he Lagos State Governor, Mr. Akinwunmi Ambode has appointed Mrs. Teju Abisoye as the Acting Exec T utive Secretary (ES) of the Lagos State Employment Trust Fund (LSETF) with effect from April 1st, 2019 pend- ing confirmation by the Lagos State House of Assembly. Prior to assuming the role of Acting ES, Mrs. Abisoye was formerly the Director of Programmes and Coordination of the LSETF. Mrs. Abisoye is a lawyer with extensive experience in development finance, project planning, execution, monitoring and evaluation of humanitarian projects, government interventions and invest- ment opportunities. Prior to joining LSETF, she served as Director (Post Award Support) of YouWIN! where she was responsible for managing consultants nationwide to provide training, monitoring & evaluation for a minimum of 1,200 Awardees annually. She has also managed the affairs of a Non-Government Organization based in Lagos. THE LSETF 3-YEAR RAPID PROGRESS AND THE 90,000 JOB CREATION FEAT ince the establishment of the LSETF three years ago, it has keenly demonstrated transp arency and accountability in all its activities, principles that represent some of The S Fund’s core values. The LSETF has continued to grow in leaps and bounds, earning public support and securing partnerships with key players in the public and private sector as well as multinational corpo- rations. Recently, the LSETF presented its 3-year social impact assessment report. The impact assess- ment exercise carried out with support from Ford Foundation, measured the achievements of the Fund’s interventions, documented the lessons learnt, and made recommendations on how to enhance the Fund’s performance in the future. -

Nigeria-Singapore Relations Seven-Point Agenda Nigerian Economy Update Nigerian Economy: Attracting Investments 2008

Nigeria-Singapore Relations Seven-point Agenda Nigerian Economy Update Nigerian Economy: Attracting Investments 2008 A SPECIAL PUBLICATION BY THE HIGH COMMISSION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA IN SINGAPORE s/LAM!DSXMM PDF0- C M Y CM MY CY CMY The Brand Behind The Brands K Integrated from farm to factory gate Managing Risk at Every Stage ORIGIN CUSTOMER Farming Origination Logistics Processing Marketing Trading & Solutions Distribution & Services The Global Supply Chain Leader Olam is a We manage each activity in the supply to create value, at every level, for our leading global supply chain manager of chain from origination to processing, customers, shareholders and employees agricultural products and food ingredients. logistics, marketing and distribution. We alike. We will continue to pursue profitable Our distinctive position is based both on therefore offer an end-to-end supply chain growth because, at Olam, we believe the strength of our origination capability solution to our customers. Our complete creating value is our business. and our strong presence in the destination integration allows us to add value and markets worldwide. We operate an manage risk along the entire supply chain integrated supply chain for 16 products in from the farm gate in the origins to our 56 countries, sourcing from over 40 origins customer’s factory gate. and supplying to more than 6,500 customers U OriginÊÊÊUÊMarketing Office in over 60 destination markets. We are We are committed to supporting the suppliers to many of the world’s most community and protecting the environment Our Businesses: Cashew, Other Edible Nuts, i>Ã]Ê-iÃ>i]Ê-«ViÃÊUÊ V>]Ê vvii]Ê- i>ÕÌÃÊ prominent brands and have a reputation in every country in which we operate. -

Subnational Governance and Socio-Economic Development in a Federal Political System: a Case Study of Lagos State, Nigeria

SUBNATIONAL GOVERNANCE AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN A FEDERAL POLITICAL SYSTEM: A CASE STUDY OF LAGOS STATE, NIGERIA. SO Oloruntoba University of Lagos ABSTRACT The main objective of any responsible government is the provision of the good life to citizens. In a bid to achieve this important objective, political elites or exter- nal powers (as the case may be) have adopted various political arrangements which suit the structural, historical cultural and functional circumstances of the countries conerned. One of such political arrangements is federalism. Whereas explanatory framework connotes a political arrangement where each of the subordinate units has autonomy over their sphere of influence. Nigeria is one of three countries in Africa, whose federal arrangement has subsisted since it was first structured as such by the Littleton Constitution of 1954. Although the many years of military rule has done incalculable damage to the practice of federal- ism in the country, Nigeria remains a federal state till today. However, there are concerns over the ability of the state as presently constituted to deliver the com- mon good to the people. Such concerns are connected to the persistent high rate of poverty, unemployment and insecurity. Previous and current scholarly works on socio-economic performance of the country have been focused on the national government. This approach overlooks the possibilities that sub-na- tional governments, especially at the state level holds for socio-economic de- velopment in the country. The point of departure of this article is to fill this lacuna by examining the socio-economic development of Lagos state, especially since 1999. -

Seplat's Activities Impacting Nigeria's Economy, Domestic Gas Supply

JUNE 2019 VOL.2 NO.4 www.tbiafrica.com N500, $20, £10 OB3, AKK PIPELINES: ECONOMIC BARU: A TRANSFORMATIONAL PROJECTS – OILSERV BOSS TRANSFORMATIONAL 9TH NATIONAL ASSEMBLY: WHAT HOPE FOR NIGERIANS? ACHIEVER AND REFORMIST SEPLAT’S ACTIVITIES IMPACTING NIGERIA’S ECONOMY, DOMESTIC GAS SUPPLY DRIVING 30% OF ELECTRICITY GENERATION Energy JUNE 2019 2 Energy JUNE 2019 Editor’s Note temporaries. Its operational and safety recently said the nation’s inflation rate standards align with international best increased to 11.40 per cent in May from practices, hence it wasn’t difficult for 11.37 per cent recorded in April, adding the management to take it to local and that the figure was 0.03 per cent higher international capital markets. Today, Se- than the rate recorded in April 2019. plat is the only Nigerian company fully Traffic gridlock in Lagos has become listed on both the Nigerian and London nightmarish and it gets worse by the Stock Exchanges. day as a result of heavy downpour. The Company has continued to strive Will the administration of Babajide to increase reserves and outputs from Sanwo-Olu walk the talk, or will it end its oil and gas blocks. Through its like the toothless bulldog that barks strategic implementation of redevel- without biting? opment work programme and drilling DR. NJIDEKA KELLEY In our political economy column, we campaign, the Company has been able looked at the expectations of Nigerian eplat Petroleum Development to grow production from mere 14,000 from members of the 9th National As- Company Plc has distinguished barrels of oil per day (bopd) to over sembly, highlighting the achievements itself as an outstanding and con- 84,000 bopd. -

1F35e3e1-Thisday-Jul

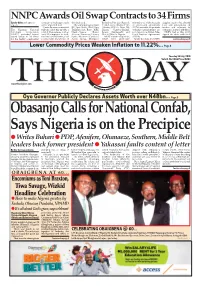

NNPC Awards Oil Swap Contracts to 34 Firms Ejiofor Alike with agency contracts to exchange crude the deals said. Barbedos/Petrogas/Rainoil; referred to as offshore crude supplies crude oil to selected reports oil for imported fuel. The winning groups include: UTM/Levene/Matrix/Petra oil processing agreements local and international oil Under the new contract that BP/Aym Shafa; Vitol/Varo; Atlantic; TOTSA; Duke Oil; (OPAs) and crude-for-products traders and refineries in The Nigerian National will take effect this month, a Trafigura/AA Rano; MRS; Sahara; Gunvor/Maikifi; exchange arrangements, are exchange for petrol and diesel. Petroleum Corporation total of 15 groupings, with at Oando/Cepsa; Bono/ Litasco /Brittania-U; and now known as Direct Sale- NNPC had in May 2017, (NNPC) yesterday issued least 34 companies in total, Akleen/Amazon/Eterna; Mocoh/Mocoh Nigeria. Direct Purchase Agreements signed the deals with local award letters to oil firms received award letters, four Eyrie/Masters/Cassiva/ NNPC’s crude swap deals, (DSDP). for the highly sought-after sources with knowledge of Asean Group; Mercuria/ which were previously Under the deals, the NNPC Continued on page 8 Lower Commodity Prices Weaken Inflation to 11.22%... Page 8 Tuesday 16 July, 2019 Vol 24. No 8863 Price: N250 www.thisdaylive.com T RU N TH & REASO Oyo Governor Publicly Declares Assets Worth over N48bn... Page 9 Obasanjo Calls for National Confab, Says Nigeria is on the Precipice Writes Buhari PDP, Afenifere, Ohanaeze, Southern, Middle Belt leaders back former president Yakassai faults content of letter By Our Correspondents plunging into an abyss of before Nigeria witnesses the varied reactions from some aligned with Obasanjo’s Forum (ACF), Alhaji Tanko insecurity. -

L'état Des Etats Au Nigéria

Service économique régional L’état des Etats au Nigéria 1 Ambassade de France au Nigéria European Union Crescent Off Constitution Avenue Central Business District, Abuja Clause de non-responsabilité : le Service économique s’efforce de diffuser des informations exactes et à jour, et corrigera, dans la mesure du possible, les erreurs qui lui seront signalées. Toutefois, il ne peut en aucun cas être tenu responsable de l’utilisation et de l’interprétation de l’information contenue dans cette publication. L’information sur les projets soutenus par l’Agence Française de Développement (AFD) est donnée à titre purement indicatif. Elle n’est ni exhaustive, ni contractuelle. Un classement par Etats peut être sujet à interprétation, notamment pour des projets nationaux (relatifs à la culture, à la gouvernance…) ou régionaux (coordonnées par la CEDEAO) non mentionnés dans le document. Ce classement n’emporte aucun jugement de valeur et n’est pas une justification de l’aide publique apportée par la France à un Etat fédéré plutôt qu’à un autre. Il peut également être soumis à des changements indépendants de la volonté de l’AFD. 2 Ambassade de France au Nigéria European Union Crescent Off Constitution Avenue Central Business District, Abuja SOMMAIRE Avant-propos .................................................................................................................................................4 Etat d’Abia (Sud-Est) ......................................................................................................................................6 -

Download Our Brochure

THE NEW GATEWAY TO AFRICA THE FUTURE IS NOW Lagos is the economic capital of Nigeria, The gateway to the continent needs a World’s Fastest Population of Lagos Population of Eko Atlantic the most populated country in Africa. new headquarters. Eko Atlantic is the answer. Population With its coastal location and abundant natural resources, Lagos is ideally positioned Rising on land reclaimed from the Growth to take a leading role in the African economy Atlantic Ocean off Victoria Island in and become a major global force, especially Lagos, Eko Atlantic is Africa’s brand new with a population of 18 million, which is city. It will create prosperity and will be expected to soar to 25 million by 2015. where business gets done. MORE THAN A CITY Eko Atlantic is more than a city though. It’s a For investors For business For residents and clear vision of the future. It creates a space to live and work, seemingly out of thin air. Eko Atlantic offers one of the world’s most Eko Atlantic will offer a prestigious business commuters By reclaiming eroded land, an oceanfront exciting opportunities to harvest the potential address with remarkable efficiency, oceanfront It will offer an ideal base for home life, wonder is not only evolving rapidly, but of Africa. The financial hub of Africa’s fastest vistas and smooth access making it a compelling with all that is expected from 21st century it is also providing a positive response to growing nation, Lagos is poised to be one of place to work. comforts and convenience all primarily with worldwide issues such as population growth the megacities of the world. -

Lagos State Poctket Factfinder

HISTORY Before the creation of the States in 1967, the identity of Lagos was restricted to the Lagos Island of Eko (Bini word for war camp). The first settlers in Eko were the Aworis, who were mostly hunters and fishermen. They had migrated from Ile-Ife by stages to the coast at Ebute- Metta. The Aworis were later reinforced by a band of Benin warriors and joined by other Yoruba elements who settled on the mainland for a while till the danger of an attack by the warring tribes plaguing Yorubaland drove them to seek the security of the nearest island, Iddo, from where they spread to Eko. By 1851 after the abolition of the slave trade, there was a great attraction to Lagos by the repatriates. First were the Saro, mainly freed Yoruba captives and their descendants who, having been set ashore in Sierra Leone, responded to the pull of their homeland, and returned in successive waves to Lagos. Having had the privilege of Western education and christianity, they made remarkable contributions to education and the rapid modernisation of Lagos. They were granted land to settle in the Olowogbowo and Breadfruit areas of the island. The Brazilian returnees, the Aguda, also started arriving in Lagos in the mid-19th century and brought with them the skills they had acquired in Brazil. Most of them were master-builders, carpenters and masons, and gave the distinct charaterisitics of Brazilian architecture to their residential buildings at Bamgbose and Campos Square areas which form a large proportion of architectural richness of the city. -

Booklet Housing

Rent-To-Own ALL YOU NEED TO KNOW LAGOS STATE MINISTRY OF HOUSING All you Need to Know OUR VISION LAGOS MEGA CITY WITH ADEQUATE HOUSING FOR ITS CITIZENRY OUR MISSION TO ENSURE THE PROVISION OF ADEQUATE AND GOOD QUALITY HOUSING IN LAGOS MEGA CITY AND FACILITATE EASY ACCESS OF ITS CITIZENS TO HOME OWNERSHIP 1 All you Need to Know (1)Q: What is the Rent – To – Own Policy about? A: The Rent-to-Own Policy introduced by the administration of Governor Akinwunmi Ambode is aimed at making housing more readily available, accessible and affordable for the low and middle income earners. This policy is to ensure that the State Government lives up to its social obligation to provide affordable shelter to its citizens and assist first time buyers to acquire their own homes. Through this policy, prospective home owners make a 5% down payment, take possession and pay up the remaining balance as rent towards the ownership of the property over a period of 10years. Sir Micheal Otedola Estate, Odoragunshin, Epe 336 units (2)Q: How does it work? A: Eligibility Criteria i. Applicant must be primarily resident in Lagos State and will be required to submit a copy of their Lagos State Residents Registration Card (LASRRA). ii. Applicant must be a First Time Buyer iii. Applicant must be 21years Old and above. iv. Only tax compliant resident will be eligible under the Lagos State Rent-To-Own policy and must provide the proof of tax payment. 2 All you Need to Know v. Applicant must be able to make the 5% commitment fee payment and the balance is spread monthly at a fixed rent over a period of ten (10) years. -

Fani-Kayode Will Serve Imonth

COVID-19: We’ve PDP faction disowns built resilience into Oyinlola's intervention our health system in Makinde/Fayose feud PAGE 10 PAGE 5 Vol. 1 , No. 5 March 14, 2021 www.nigeriangateway.com N200 Why we are reviving PAGE 3 agro-cargo airport –Abiodun Herders/Farmers Clashes: Ogun’ll serve as model for harmonious living –Oladele PAGE 7 Why we removed Ambode as Lagos State Governor –Tinubu PAGE 5 PAGE 4 Justice Ngwuta Governor Dapo Abiodun of Ogun State presenting a document to Senator Smart Adeyemi during the visit of the Senate didn't die of COVID-19 Committee on Aviation to the Governor... recently — Supreme Court Nigeria loses $10bn to Illicit financial flows –ICPC PAGE 13 March 14, 2021 |2 |3 Business MarNche 14,w 2021s FOREIGN Biden appoints another Nigerian Why my administration will build Domestic, foreign portfolio investment drop by 13.66% as Director of Global Health rading figures from — Abiodun January 2021 released January 2020, total transactions executed 28 per cent. Agro Cargo Airport Foreign transactions Nigerian market transactions decreased between December 2020 and Resources recently A comparison of increased by 18.45 per By Folaranmi Akorede Toperators on the The report showed that, marginally by N3bn (1.27 January 2021 revealed that domestic transactions in cent from N616bn to Domestic and Foreign as at January 31, 2021, total per cent). total domestic transactions t h e r e v i e w m o n t h s N729bn. he Ogun State governor, Portfolio Investment flows transactions at the nation's According to the report, decreased by 7.21 per cent revealed that retail T o t a l d o m e s t i c Dapo Abiodun, has declined in January 2021 by bourse decreased by 13.66 domestic investors out- f r o m N 1 9 9 . -

Buhari Has a History of Smuggling in Looted Funds – Atiku INNOCENT ODOH, Abuja Muhammadu Buhari That He Is History Shows That Rather Than the Country

businessday market monitor NSE Bitcoin Everdon Bureau De Change FMDQ Close FOREIGN EXCHANGE TREASURY BILLS FGN BONDS - $43.19bn Foreign Reserve Market Spot ($/N) 3M 6M 5 Y 10 Y 20 Y Biggest Gainer Biggest Loser BUY SELL Cross Rates - GBP-$:1.28 YUANY-N53.06 ₦1,297,150.35 -3.18 pc 0.29 0.00 Dangcem Stanbic $-N 359.00 362.00 I&E FX Window 364.00 -0.02 -0.01 0.15 N184.8 0.98 pc N47.95 -9.95 pc Commodities Powered by £-N 456.00 464.00 CBN Official Rate 307.00 14.27 13.41 14.57 15.57 15.54 Cocoa Gold Crude Oil 30,962.26 €-N 405.00 413.00 Currency Futures NGUS MAR 27 2019 NGUS JUN 26 2019 NGUS DEC 24 2019 US$2,415.00 $1,283.90 $53.33 ($/N) 364.89 365.34 366.24 NEWS YOU CAN TRUST I **TUESDAY 01 JANUARY 2019 I VOL. 15, NO 214 I N300 g www. g @ g Five things businesses must prepare for in 2019 CCNN tops market gainers in 2018 LOLADE AKINMURELE he New Year is upon us and there are five things Tcorporate boardrooms in Nigeria must critically examine ahead expanded listing from merger in preparing for the year. Naira downside LOLADE AKINMURELE change in 2018, after advancing Approvals came from the Monday. 104 percent. Securities and Exchange Com- With this, the shares of the The first thing and probably ement Company the most important is what the There is optimism going into mission, the Nigerian Stock expanded entity are expected to of Northern Nigeria the New Year for the cement Exchange (NSE), a Federal High be listed on the Nigerian Stock New Year holds for the naira.