Kamasan Art in Museum Collections ‘Entangled’ Histories of Art Collecting in Bali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpreting Balinese Culture

Interpreting Balinese Culture: Representation and Identity by Julie A Sumerta A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Public Issues Anthropology Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2011 © Julie A. Sumerta 2011 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. Julie A. Sumerta ii Abstract The representation of Balinese people and culture within scholarship throughout the 20th century and into the most recent 21st century studies is examined. Important questions are considered, such as: What major themes can be found within the literature?; Which scholars have most influenced the discourse?; How has Bali been presented within undergraduate anthropology textbooks, which scholars have been considered; and how have the Balinese been affected by scholarly representation? Consideration is also given to scholars who are Balinese and doing their own research on Bali, an area that has not received much attention. The results of this study indicate that notions of Balinese culture and identity have been largely constructed by “Outsiders”: 14th-19th century European traders and early theorists; Dutch colonizers; other Indonesians; and first and second wave twentieth century scholars, including, to a large degree, anthropologists. Notions of Balinese culture, and of culture itself, have been vigorously critiqued and deconstructed to such an extent that is difficult to determine whether or not the issue of what it is that constitutes Balinese culture has conclusively been answered. -

Ubud: from the Origins to 19201

Ubud: From The Origins to 19201 Jean Couteau* Abstract Today’s historis often tries to weave together unquestionable facts with a narrative that consciously gives room to past myths and legends. The following article about the famous “cultural” resort of Ubud freely applies this approach to history. Myths and legends about the origin of Ubud combine with unquestionable historical facts to convey, beyond the Ubud’s raw history proper, the prevailing athmosphere of Ubud’s pre-modern past. Thus the mythical seer Resi Merkandaya is made to appear alongside the story of the kembar buncing (fraternal, non-identical twins) of the House of Ubud, and the history of Western presence and intervention. Keywords: prince of Ubud, knowledge of tradition, modernizing Bali Ubud: In the Legendary Haze of History o those who truly know Ubud, that is, Ubud such as it was, Twhen its life was still governed, through rites, by the har- monious encounter of Man and Nature, Campuhan is a magical spot, which marks Ubud as a place bestowed by the favors of the * Dr. Jean Couteau is a French writer living in Bali who publishes extensively on a large variety of topics in French, English and Indonesian. He is mainly known in Indonesia for his essays and his writings on the arts. He is the senior editor of the international art magazine C-Arts and a lecturer at the Indonesian Art Institute (Institut Seni Indonesia/ ISI) in Denpasar. 1 This text rests on three main sources of information: Hilbery Rosemary, Reminiscences of a Balinese Prince, Tjokorde Gde Agung Sukawati, SE Asia Paper No 14, SE Asian Studies, University of Hawai, 1979; an interview of Cokorde Niang Isteri, the wife of Cokorde Agung Sukawati; and in-depth interviews of Cokorde Atun, Cokorde Agung Sukawati’s daughter. -

A Case Study of Batik in Java and Santiniketan

Universiteit Leiden Journey of Textile Designs: A Case Study of Batik in Java and Santiniketan Master Thesis, Asian Studies (60 EC) 2015-16 Name of student: Deboshree Banerjee Student Number: s1684337 Date: 1st September 2016 Supervisors: Prof. dr. N.K. Wickramasinghe-Samarasinghe Prof. dr. P.R. Kanungo Table of Contents Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures and Tables......................................................................................................... iv Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... v Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Textiles: A Medium of Cultural Studies ......................................................................... 1 1.2. Diffusion Theory ............................................................................................................. 3 1.3. Literature Review: Javanese and Santiniketan Batik ...................................................... 4 1.3.1. Javanese Batik .......................................................................................................... 5 1.3.2 Santiniketan Batik ..................................................................................................... 7 1.4. Proposed Hypothesis ...................................................................................................... -

Perkembangan Revitalisasi Kesenian Berbasis Budaya Panji Di Bali1) Oleh Prof

1 Perkembangan Revitalisasi Kesenian Berbasis Budaya Panji di Bali1) Oleh Prof. Dr. I Nyoman Suarka, M.Hum. Program Studi Sastra Jawa Kuna, FIB, UNUD Pendahuluan Bangsa Indonesia memiliki kekayaan budaya yang diwariskan secara turun-temurun meliputi periode waktu yang panjang. Kekayaan budaya bangsa Indonesia yang terwarisi hingga hari ini ada yang berupa unsur budaya benda (tangible), seperti keris, wayang, gamelan, batik, candi, bangunan kuno, dan lain-lain; serta ada yang berupa unsur budaya tak benda (intangible), seperti sastra, bahasa, kesenian, pengetahuan, ritual, dan lain-lain. Kekayaan budaya bangsa tersebut merepresentasikan filosofi, nilai dasar, karakter, dan keragaman adab. Sastra Panji adalah salah satu kekayaan budaya bangsa Indonesia. Sastra Panji merupakan sastra asli Nusantara (Sedyawati, 2007:269). Sastra Panji diperkirakan diciptakan pada masa kejayaan Majapahit. Sastra Panji dapat dipandang sebagai revolusi kesusastraan terhadap tradisi sastra lama (tradisi sastra kakawin) (Poerbatjaraka,1988:237). Sebagaimana dikatakan Zoetmulder (1985:533) bahwa kisah-kisah Panji disajikan secara eksklusif dalam bentuk kidung dan menggunakan bahasa Jawa Pertengahan. Persebarannya ke pelosok Nusantara diresepsi ke dalam kesusastraan berbagai bahasa Nusantara. Sastra Panji telah banyak dibicarakan ataupun diteliti oleh para pakar, baik dari dalam negeri maupun luar negeri, antara lain Rassers (1922) menulis tentang kisah Panji dalam tulisan berjudul “De Pandji-roman”; Berg meneliti kidung Harsawijaya (1931) dan menerbitkan artikel -

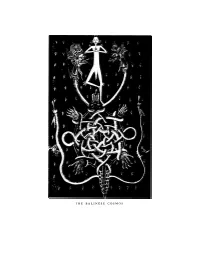

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a R G a R Et M E a D ' S B a L in E S E : T H E F Itting S Y M B O Ls O F T H E a M E R Ic a N D R E a M 1

THE BALINESE COSMOS M a r g a r et M e a d ' s B a l in e s e : T h e F itting S y m b o ls o f t h e A m e r ic a n D r e a m 1 Tessel Pollmann Bali celebrates its day of consecrated silence. It is Nyepi, New Year. It is 1936. Nothing disturbs the peace of the rice-fields; on this day, according to Balinese adat, everybody has to stay in his compound. On the asphalt road only a patrol is visible—Balinese men watching the silence. And then—unexpected—the silence is broken. The thundering noise of an engine is heard. It is the sound of a motorcar. The alarmed patrollers stop the car. The driver talks to them. They shrink back: the driver has told them that he works for the KPM. The men realize that they are powerless. What can they do against the *1 want to express my gratitude to Dr. Henk Schulte Nordholt (University of Amsterdam) who assisted me throughout the research and the writing of this article. The interviews on Bali were made possible by Geoffrey Robinson who gave me in Bali every conceivable assistance of a scholarly and practical kind. The assistance of the staff of Olin Libary, Cornell University was invaluable. For this article I used the following general sources: Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, Balinese Character: A Photographic Analysis (New York: New York Academy of Sciences, 1942); Geoffrey Gorer, Bali and Angkor, A 1930's Trip Looking at Life and Death (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987); Jane Howard, Margaret Mead, a Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984); Colin McPhee, A House in Bali (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1979; orig. -

Download Download

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR INNOVATION EDUCATION AND RESEARCH ONLINE ISSN: 2411-2933 PRINT - ISSN: 2411-3123 INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIVE RESEARCH FOUNDATION AND PUBLISHER (IERFP) Volume- 5 Number- 8 August Edition International Journal for Innovation Education and Research www.ijier.net Vol:-5 No-8, 2017 About the Journal Name: International Journal for Innovation Education and Research Publisher: Shubash Biswas International Journal for Innovation Education and Research 44/1 Kallyanpur Main road Mirpur, Dhaka 1207 Bangladesh. Tel: +8801827488077 Copyright: The journal or any part thereof may be reproduced for academic and research purposes with an appropriate acknowledgment and a copy of the publication sent to the editor. Written permission of the editor is required when the intended reproduction is for commercial purposes. All opinions, information’s and data published in the articles are an overall responsibility to the author(s). The editorial board does not accept any responsibility for the views expressed in the paper. Edition: August 2017 Publication fee: $100 and overseas. International Educative Research Foundation and Publisher ©2017 Online-ISSN 2411-2933, Print-ISSN 2411-3123 August 2017 Editorial Dear authors, reviewers, and readers It has been a month since I was given the privilege to serve as the Chief Editor of the International Journal for Innovation Education and Research (IJIER). It is a great pleasure for me to shoulder this duty and to welcome you to THE VOL-5, ISSUE-8 of IJIER which is scheduled to be published on 31st August 2017. International Journal for Innovation Education and Research (IJIER) is an open access, peer-reviewed and refereed multidisciplinary journal which is published by the International Educative Research Foundation and Publisher (IERFP). -

Climate Change Conference 2007

1 climate chanuge cnonference 2OO7 c o n t e n t CONFERENCE OUTLINE 2 GENERAL INFORMATION 3 ACCOMMODATION 10 OPTIONAL TOURS 18 PRE / POST-CONFERENCE TOURS 19 conference outline general information CONFERENCE DATES 3 - 14 December 2007 VENUE Bali International Convention Centre (BICC) P.O. Box 36, Nusa Dua, Bali 80363, INDONESIA 2 Tel. (62 361) 771 906 3 Fax. (62 361) 772 047 http://www.baliconvention.com OVERVIEW SCHEDULE Thirteenth session of the Conference of the Parties (COP 13) Third session of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Kyoto Protocol (CMP 3) Twenty-seventh session of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA 27) Twenty-seventh session of the Subsidiary Body for Implementation (SBI 27) Resumed fourth session of the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I INDONESIA Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG 4) Situated between two continents and two oceans, the Indian and Pacific oceans, Indonesia is the Note: world's largest archipelago comprising some 17,508 islands that stretch across the equator for This schedule is intended to assist participants with their planning prior to attending the sessions. more than 5,000 miles. Straddling the equator, Indonesia is distinctly tropical with two seasons: It will be updated as new information becomes available on the website of the United Nations dry and rainy season. With its geographical location in South East Asia, Indonesia is accessible for Framework Convention on Climate change <unfccc.int>. Once the sessions are underway, please delegates regardless of the region they are from. -

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer L. Goodlander August 2010 © 2010 Jennifer L. Goodlander. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali by JENNIFER L. GOODLANDER has been approved for the Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Theater Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GOODLANDER, JENNIFER L., Ph.D., August 2010, Interdisciplinary Arts Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali (248 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee The role of women in Bali must be understood in relationship to tradition, because “tradition” is an important concept for analyzing Balinese culture, social hierarchy, religious expression, and politics. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is considered an important Balinese tradition because it connects a mythic past to a political present through public, and often religiously significant ritual performance. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and priest. Until recently, the dalang has always been male, but now women are studying and performing as dalangs. In order to determine what women in these “non-traditional” roles means for gender hierarchy and the status of these arts as “traditional,” I argue that “tradition” must be understood in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a “traditional” society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by “tradition,” and the performing arts as both “traditional” and as a conduit for “tradition.” This dissertation is divided into three sections, beginning in chapters two and three, with a general focus on the “tradition” of wayang kulit through an analysis of the objects and practices of performance. -

Weekly Schedule of Cultural Performances in Ubud—2014

Weekly Schedule of Cultural Performances in Ubud—2014 NOTE: pick up a current schedule from your hotel as details may have changed since this schedule was published. I have posted this online for illustrative purposes only. Entrance fees are between Rp 50.000- 190 000. Tickets for performances can be obtained at Ubud Tourist Information JI Raya Ubud. Phone 973285, from ticket sellers on the street or at the place of the performance. The price is the same wherever you buy it. Performance Venue and Time (PM) Performance Venue and Time (PM) SUNDAYS THURSDAYS Legong of Mahabrata Ubud Palace 7.30 Legong Trance & Ubud Palace 7.30 Kecak Fire & Trance Dance Padang Tegal Kaja 7.00 Paradise Dance Wayang Kulit (Shadow Puppet) Oka Kartini 8.00 Kecak Puri Agung Peliatan*** 7.30 The Peliatan Master Arma Museum*** 7.30 Legong Dance Pura Desa Kutuh*** 7.30 Janger Lotus Pond Open Stage 7.30 Barong & Keris Pura Dalem Ubud 7.30 Jegog (Bamboo Gamelan) Bentuyung Village*** 7.00 Barong & Child Ubud Water Palace 7.30 Kecak Fire & Trance Dance Batukaru Temple 7.30 Dance Dancers & Musician of Peliatan Balerung Mandera 7.30 Kecak Pura Taman Sari 7.30 Pondok Pekak Gamelan & Bale Banjar Ubud Kelod 7.30 Kecak Batukaru Temple 7.30 Dance Wayang Kulit Pondok Bamboo 8.00 Legong Dance Pura Keloncing 7.30 MONDAYS Legong Dances Ubud Palace 7.30 FRIDAYS Kecak Fire (Monkey Chant Junjungan Village*** 7.00 Barong Dance Ubud Palace 7.30 Dance) Legong & Barong Balerung Stage 7.30 Barong & Keris Dance Wantilan 7.00 Kecak & Fire Dance Pura Padang Kertha 7.30 Kecak Ramayana & Fire -

Nilai Patriotisme Dalam Geguritan Wira Carita Puputan Margarana

1 NILAI PATRIOTISME DALAM GEGURITAN WIRA CARITA PUPUTAN MARGARANA PERSPEKTIF PEMBANGUNAN KARAKTER BANGSA I Wayan Cika dan I Made Soreyana Program Studi Sastra Indonesia Fakultas Sastra dan Budaya, Universitas Udayana Jalan Nias 13 Denpasar. Kode Post:80114 Telp/Fax: (0361) 2224121, E-mail : [email protected] (Kode Makalah: P-PNL-163) ABSTRAK Salah satu karya sastra geguritan yang dijadikan objek dalam penelitian ini adalah Geguritan Wira Carita Puputan Margarana (GWCPM). GWCPM sangat menarik untuk dikaji karena GWCPM berada antara fakta dan fiksi, artinya GWCPM ditulis dalam bentuk karya sastra geguritan dan isinya menceritakan fakta sejarah yang benar-benar terjadi, yaitu peristiwa perang antara pasukan I Gusti Ngurah Rai (Pasukan Ciung Wanara) melawan Belanda pada tanggal 20 November 1946. Penelitian ini adalah sebuah penelitian kualitatif yang dianalisis dengan menggunakan teori semiotika sebagai landasan, dibantu dengan teori objektif, dan ditunjang dengan metode hermeutika. Pengumpulan data dilakukan dengan metode studi pustaka untuk mendapatkan naskah dan teks GWCPM. Hasil analisis menunjukkan bahwa GWCPM dibentuk oleh 9 pupuh dengan 15 pergantian. Bahasa yang digunakan adalah bahasa Bali, Jawa Kuna, Sansekerta, dan bahasa Belanda. Tema yang diangkat adalah tentang patriotisme, yaitu kegigihan para pejuang untuk membela dan mempertahankan kemerdekaan bangsa. Para pejuang tidak gentar mengorbankan jiwa dan raganya, demi kepentingan nusa dan bangsa. Selain itu, ditemukan juga nilai kejujuran, kesetiakawanan, nilai religius, nilai persatuan, dan nilai sejarah. Nilai-nilai tersebut dapat dijadikan pedoman dalam membangun karakter bangsa. Amanat yang dapat dipetik adalah agar generasi muda dapat mengetahui, memahami dan meneladani nilai-nilai luhur yang tercermin dalam GWCPM dan bisa menghargai para pejuang yang telah gugur sebagai kusuma bangsa. -

Global Kamasan Siobhan Campbell 1*

Global Kamasan Siobhan Campbell 1* Abstract The painting tradition of Kamasan is often cited as an example of the resilience of traditional Balinese culture in the face of globalisation and the emergence of new forms of art and material culture. This article explores the painting tradition of Kamasan village in East Bali and it’s relationship to the collecting of Balinese art. While Kamasan painting retains important social and religious functions in local culture, the village has a history of interactions between global and local players which has resulted in paintings moving beyond Kamasan to circulate in various locations around Bali and the world. Rather than contribute to the demise of a local religious or cultural practice, exploring the circulation of paintings and the relationship between producers and collectors reveals the nuanced interplay of local and global which characterises the ongoing transformations in traditional cultural practice. Key Words: Kamasan, painting, traditional, contemporary, art, collecting Introduction n 2009 a retrospective was held of works by a major IKamasan artist in two private art galleries in Bali and Java. The Griya Santrian Gallery in Sanur and the Sangkring Art Space in Yogyakarta belong to the realm of contemporary Indonesian art, and the positioning of artist I Nyoman Mandra within this setting revealed the shifting boundaries 1 Siobhan Campbell is a postgraduate research student at the University of Sydney working on a project titled Collecting Balinese Art: the Forge Collection of Balinese Paintings at the Australian Museum. She completed undergraduate studies at the University of New South Wales in Indonesian language and history and is also a qualified Indonesian/English language translator. -

Overview of Diplomatic Letters Listed Geographically by Region

Overview of Diplomatic Letters Listed Geographically by Region Region: Africa Egypt Location Place Alternative Name Cairo Saladin Citadel of Cairo Coordinates (lat/long):30.026608 31.259968 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 1 recieved:0 total: 1 Ethiopia Abyssinia Location Place Alternative Name Addis Ababa Coordinates (lat/long):8.988611 38.747932 Accurate?N Letters sent: 1 recieved:2 total: 3 Gondar Fasil Ghebbi Coordinates (lat/long):12.608048 37.469666 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 2 recieved:2 total: 4 South Africa Location Place Alternative Name Cape of Good Hope Castle of Good Hope Coordinates (lat/long):-33.925869 18.427623 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 9 recieved:0 total: 9 The castle was were most political exiles were kept Robben Island Robben Island Cape Town Coordinates (lat/long):-33.807607 18.371231 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 1 recieved:0 total: 1 Region: East Asia www.sejarah-nusantara.anri.go.id - ANRI TCF 2015 Page 1 of 44 Overview of Diplomatic Letters Listed Geographically by Region China Location Place Alternative Name Amoy Xiamen Coordinates (lat/long):24.479198 118.109207 Accurate?N Letters sent: 8 recieved:3 total: 11 Beijing Forbidden city Coordinates (lat/long):39.917906 116.397032 Accurate?Y Letters sent: 11 recieved:7 total: 18 Canton Guagnzhou Coordinates (lat/long):23.125598 113.227844 Accurate?N Letters sent: 7 recieved:4 total: 11 Chi Engling Coordinates (lat/long):23.646272 116.626946 Accurate?N Letters sent: 1 recieved:0 total: 1 Geodata unreliable Fuzhou Coordinates (lat/long):26.05016 119.31839 Accurate?N Letters sent: 32