Communication Dialectics in a Musical Community: the Anti- Socialization of Newcomers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson

The Interplay of Authority, Masculinity, and Signification in the “Grunge Killed Glam Metal” Narrative by Holly Johnson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2014, Holly Johnson ii Abstract This thesis will deconstruct the "grunge killed '80s metal” narrative, to reveal the idealization by certain critics and musicians of that which is deemed to be authentic, honest, and natural subculture. The central theme is an analysis of the conflicting masculinities of glam metal and grunge music, and how these gender roles are developed and reproduced. I will also demonstrate how, although the idealized authentic subculture is positioned in opposition to the mainstream, it does not in actuality exist outside of the system of commercialism. The problematic nature of this idealization will be examined with regard to the layers of complexity involved in popular rock music genre evolution, involving the inevitable progression from a subculture to the mainstream that occurred with both glam metal and grunge. I will illustrate the ways in which the process of signification functions within rock music to construct masculinities and within subcultures to negotiate authenticity. iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank firstly my academic advisor Dr. William Echard for his continued patience with me during the thesis writing process and for his invaluable guidance. I also would like to send a big thank you to Dr. James Deaville, the head of Music and Culture program, who has given me much assistance along the way. -

Grunge Is Dead Is an Oral History in the Tradition of Please Kill Me, the Seminal History of Punk

THE ORAL SEATTLE ROCK MUSIC HISTORY OF GREG PRATO WEAVING TOGETHER THE DEFINITIVE STORY OF THE SEATTLE MUSIC SCENE IN THE WORDS OF THE PEOPLE WHO WERE THERE, GRUNGE IS DEAD IS AN ORAL HISTORY IN THE TRADITION OF PLEASE KILL ME, THE SEMINAL HISTORY OF PUNK. WITH THE INSIGHT OF MORE THAN 130 OF GRUNGE’S BIGGEST NAMES, GREG PRATO PRESENTS THE ULTIMATE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO A SOUND THAT CHANGED MUSIC FOREVER. THE GRUNGE MOVEMENT MAY HAVE THRIVED FOR ONLY A FEW YEARS, BUT IT SPAWNED SOME OF THE GREATEST ROCK BANDS OF ALL TIME: PEARL JAM, NIRVANA, ALICE IN CHAINS, AND SOUNDGARDEN. GRUNGE IS DEAD FEATURES THE FIRST-EVER INTERVIEW IN WHICH PEARL JAM’S EDDIE VEDDER WAS WILLING TO DISCUSS THE GROUP’S HISTORY IN GREAT DETAIL; ALICE IN CHAINS’ BAND MEMBERS AND LAYNE STALEY’S MOM ON STALEY’S DRUG ADDICTION AND DEATH; INSIGHTS INTO THE RIOT GRRRL MOVEMENT AND OFT-OVERLOOKED BUT HIGHLY INFLUENTIAL SEATTLE BANDS LIKE MOTHER LOVE BONE, THE MELVINS, SCREAMING TREES, AND MUDHONEY; AND MUCH MORE. GRUNGE IS DEAD DIGS DEEP, STARTING IN THE EARLY ’60S, TO EXPLAIN THE CHAIN OF EVENTS THAT GAVE WAY TO THE MUSIC. THE END RESULT IS A BOOK THAT INCLUDES A WEALTH OF PREVIOUSLY UNTOLD STORIES AND FRESH INSIGHT FOR THE LONGTIME FAN, AS WELL AS THE ESSENTIALS AND HIGHLIGHTS FOR THE NEWCOMER — THE WHOLE UNCENSORED TRUTH — IN ONE COMPREHENSIVE VOLUME. GREG PRATO IS A LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK-BASED WRITER, WHO REGULARLY WRITES FOR ALL MUSIC GUIDE, BILLBOARD.COM, ROLLING STONE.COM, RECORD COLLECTOR MAGAZINE, AND CLASSIC ROCK MAGAZINE. -

![D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4019/d841o-free-download-love-death-the-murder-of-kurt-cobain-online-144019.webp)

D841o [Free Download] Love Death: the Murder of Kurt Cobain Online

d841o [Free download] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Online [d841o.ebook] Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain Pdf Free Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook Détails sur le produit Rang parmi les ventes : #289088 dans eBooksPublié le: 2014-03-20Sorti le: 2014-03- 20Format: Ebook Kindle | File size: 26.Mb Par Max Wallace, Ian Halperin : Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Love Death: The Murder of Kurt Cobain: Commentaires clientsCommentaires clients les plus utiles0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. A couper le soufflePar TichatDu vrai journalisme investigatif. Bien écrit, très bien recherché, objectif, avec des révélations inattendues et hallucinantes.Se lit tel qu'un thriller à en oublier presque qu'il s'agit malheureusement de faits réels.0 internautes sur 0 ont trouvé ce commentaire utile. GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?Par guichardGREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ?GREAT SELLER +++ FAST, CLEAN,PERFECT ... WHAT ELSE ? Présentation de l'éditeurTHE EXPLOSIVE INVESTIGATION INTO THE DEATH OF KURT COBAIN. Friday, 8th April 1994. Kurt Cobain's body was discovered in a room above a garage in Seattle. For the attending authorities, it was an open-and-shut case of suicide. What no one knew was Cobain had been murdered. That April, Cobain went missing for several days, or so it seemed: in fact, some people knew where he was, and one of them was Courtney Love. -

The Sex Pistols: Punk Rock As Protest Rhetoric

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2002 The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric Cari Elaine Byers University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Byers, Cari Elaine, "The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric" (2002). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1423. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/yfq8-0mgs This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

KREVISS Cargo Records Thanks WW DISCORDER and All Our Retail Accounts Across the Greater Vancouver Area

FLAMING LIPS DOWN BY LWN GIRL TROUBLE BOMB ATOMIC 61 KREVISS Cargo Records thanks WW DISCORDER and all our retail accounts across the greater Vancouver area. 1992 was a good year but you wouldn't dare start 1993 without having heard: JESUS LIZARD g| SEBADOH Liar Smash Your Head IJESUS LIZARD CS/CD On The Punk Rock CS/CD On Sebadoh's songwriter Lou Barlow:"... (his) songwriting sticks to your gullet like Delve into some raw cookie dough, uncharted musical and if he ever territory. overcomes his fascination with the The holiday season sound of his own being the perfect nonsense, his time for this baby Sebadoh could be from Jesus Lizard! the next greatest band on this Hallelujah! planet". -- Spin ROCKET FROM THE CRYPT Circa: Now! CS/CD/LP San Diego's saviour of Rock'n'Roll. Forthe ones who Riff-driven monster prefer the Grinch tunes that are to Santa Claus. catchier than the common cold and The most brutal, loud enough to turn unsympathetic and your speakers into a sickeningly repulsive smoldering heap of band ever. wood and wires. A must! Wl Other titles from these fine labels fjWMMgtlllli (roue/a-GO/ are available through JANUARY 1993 "I have a responsibility to young people. They're OFFICE USE ONLY the ones who helped me get where I am today!" ISSUE #120 - Erik Estrada, former CHiPs star, now celebrity monster truck commentator and Anthony Robbins supporter. IRREGULARS REGULARS A RETROSPECT ON 1992 AIRHEAD 4 BOMB vs. THE FLAMING LIPS COWSHEAD 5 SHINDIG 9 GIRL TROUBLE SUBTEXT 11 You Don't Go To Hilltop, You VIDEOPHILTER 21 7" T\ REAL LIVE ACTION 25 MOFO'S PSYCHOSONIC PIX 26 UNDER REVIEW 26 SPINLIST. -

Feminismusbuch

give the a cigarette feminist 1 Ein Feminismusbuch. 2 @ Februar 2001 Herausgeber. Hinweis: Es 16 Gormannstr. kulturrevolution.design Gestaltung Dörte Gutschow (V Redaktion web: www.jungdemokratinnen.de email: [email protected] Fon: 0202-4938354, Fax: 0202-451123, 29c, Kielerstr. Landesverband Nordrhein-Westfalen JungdemokratInnen / Junge Linke HerausgeberInnen givegive thethe cigarettecigarette aa konnten leider nicht sämtliche Bildrechte vollständig geklärt werden. Bei Fragen wenden Sie sich bitte an die 42107 Wuppertal Feminismus : 10119 Berlin : www.k : 10119 FeminismusFeminismushandbuchhandbuch .i.S.d.P.), .i.S.d.P.), Sarah Dellmann, Lisa Zimmermann, Hella Eberhardt ulturrevolution.de Feminismus - das ist doch Frauensache!? Ein paar Gedanken über "bewegte Männer" und andere Ein Kurzüber- und Einblick in die Geschichte der deutschen Frauenbewegung Nicht mehr schlucken, Feuer spucken - Männliches Redeverhalten Und bist Du nicht willig... - Gewalt gegen Frauen und Mädchen Geschlechter in den Medien - Sozialisation durch die Warum müssen Kinder immer Jungen oder Mädchen sein? Riot Grrrls, Revolution und Frauen im Independent Rock II Die Schöne und das Biest "Gabi hat den Tarzan lii-ii-ieb..." - "Gabi hat den Tarzan Kämpferinnen für Volk Kämpferinnen für Volk I Für den Anfang Joanne Gottlieb, Gayle Wald S. 54 Joanne Gottlieb, Gayle Muttertag: Mutti ist die Beste! - Frauenbilder Und sie bewegt sich doch! Lisa Zimmermann S. 38 Lisa Zimmermann S. 30 Melanie Schreiber S. 48 Der Mythos Schönheit Smells Like Teen Spirit Smells Like Teen Dörte Gutschow S. 29 Dörte Gutschow S. 24 Tobias Ebbrecht S. 40 Tobias Hella Eberhardt S. 16 Johannes Bock S. 21 Lars Quadfasel S. 32 Tobias Ebbrecht S.8 Tobias JD/JL Bonn S.11 8. März Täter und Vaterland TKKG 3 III Not only a woman V Staat & Sex Lesben - arme diskriminierte Minderheit? Zur gesellschaftlichen Situation von Lesben Die drei Formen des Frauenhandels Jutta Oesterle-Schwerin S. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Rent Glossary of Terms

Rent Glossary of Terms 11th Street and Avenue B CBGB’s – More properly CBGB & OMFUG, a club on Bowery Ave between 1st and 2nd streets. The following is taken from the website http://www.cbgb.com. It is a history written by Hilly Kristal, the founder of CBGB and OMFUG. The question most often asked of me is, "What does CBGB stand for?" I reply, "It stands for the kind of music I intended to have, but not the kind that we became famous for: COUNTRY BLUEGRASS BLUES." The next question is always, "but what does OMFUG stand for?" and I say "That's more of what we do, It means OTHER MUSIC FOR UPLIFTING GORMANDIZERS." And what is a gormandizer? It’s a voracious eater of, in this case, MUSIC. […] The obvious follow up question is often "is this your favorite kind of music?" No!!! I've always liked all kinds but half the radio stations all over the U.S. were playing country music, cool juke boxes were playing blues and bluegrass as well as folk and country. Also, a lot of my artist/writer friends were always going off to some fiddlers convention (bluegrass concert) or blues and folk festivals. So I thought it would be a whole lot of fun to have my own club with all this kind of music playing there. Unfortunately—or perhaps FORTUNATELY—things didn't work out quite the way I 'd expected. That first year was an exercise in persistence and a trial in patience. My determination to book only musicians who played their own music instead of copying others, was indomitable. -

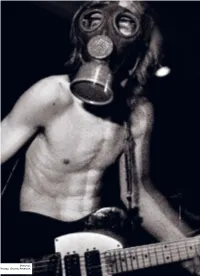

Charles Peterson …And Everett True Is 481

Dwarves Photos: Charles Peterson …and Everett True is 481. 19 years on from his first Seattle jolly on the Sub Pop account, Plan B’s publisher-at-large jets back to the Pacific Northwest to meet some old friends, exorcise some ghosts and find out what happened after grunge left town. How did we get here? Where are we going? And did the Postal Service really sell that many records? Words: Everett True Transcripts: Natalie Walker “Heavy metal is objectionable. I don’t even know comedy genius, the funniest man I’ve encountered like, ‘I have no idea what you’re doing’. But he where that [comparison] comes from. People will in the Puget Sound8. He cracks me up. No one found trusted the four of us enough to let us go into the say that Motörhead is a metal band and I totally me attractive until I changed my name. The name studio for a weekend and record with Jack. It was disagree, and I disagree that AC/DC is a metal band. slides into meaninglessness. What is the Everett True essentially a demo that became our first single.” To me, those are rock bands. There’s a lot of Chuck brand in 2008? What does Sub Pop stand for, more Berry in Motörhead. It’s really loud and distorted and than 20 years after its inception? Could Sub Pop It’s in the focus. The first time I encountered Sub amplified but it’s there – especially in the earlier have existed without Everett True? Could Everett Pop, I had 24 hours to write up my first cover feature stuff. -

Joan Jett & the Blackhearts

Joan Jett & the Blackhearts By Jaan Uhelszki As leader of her hard-rockin’ band, Jett has influenced countless young women to pick up guitars - and play loud. IF YOU HAD TO SIT DOWN AND IMAGINE THE IDEAL female rocker, what would she look like? Tight leather pants, lots of mascara, black (definitely not blond) hair, and she would have to play guitar like Chuck Berry’s long-lost daughter. She wouldn’t look like Madonna or Taylor Swift. Maybe she would look something like Ronnie Spector, a little formidable and dangerous, definitely - androgynous, for sure. In fact, if you close your eyes and think about it, she would be the spitting image of Joan Jett. ^ Jett has always brought danger, defiance, and fierceness to rock & roll. Along with the Blackhearts - Jamaican slang for loner - she has never been afraid to explore her own vulnerabilities or her darker sides, or to speak her mind. It wouldn’t be going too far to call Joan Jett the last American rock star, pursuing her considerable craft for the right reason: a devo tion to the true spirit of the music. She doesn’t just love rock & roll; she honors it. ^ Whether she’s performing in a blue burka for U.S. troops in Afghanistan, working for PETA, or honoring the slain Seattle singer Mia Zapata by recording a live album with Zapata’s band the Gits - and donating the proceeds to help fund the investigation of Zapata’s murder - her motivation is consistent. Over the years, she’s acted as spiritual advisor to Ian MacKaye, Paul Westerberg, and Peaches. -

Hipster Black Metal?

Hipster Black Metal? Deafheaven’s Sunbather and the Evolution of an (Un) popular Genre Paola Ferrero A couple of months ago a guy walks into a bar in Brooklyn and strikes up a conversation with the bartenders about heavy metal. The guy happens to mention that Deafheaven, an up-and-coming American black metal (BM) band, is going to perform at Saint Vitus, the local metal concert venue, in a couple of weeks. The bartenders immediately become confrontational, denying Deafheaven the BM ‘label of authenticity’: the band, according to them, plays ‘hipster metal’ and their singer, George Clarke, clearly sports a hipster hairstyle. Good thing they probably did not know who they were talking to: the ‘guy’ in our story is, in fact, Jonah Bayer, a contributor to Noisey, the music magazine of Vice, considered to be one of the bastions of hipster online culture. The product of that conversation, a piece entitled ‘Why are black metal fans such elitist assholes?’ was almost certainly intended as a humorous nod to the ongoing debate, generated mainly by music webzines and their readers, over Deafheaven’s inclusion in the BM canon. The article features a promo picture of the band, two young, clean- shaven guys, wearing indistinct clothing, with short haircuts and mild, neutral facial expressions, their faces made to look like they were ironically wearing black and white make up, the typical ‘corpse-paint’ of traditional, early BM. It certainly did not help that Bayer also included a picture of Inquisition, a historical BM band from Colombia formed in the early 1990s, and ridiculed their corpse-paint and black cloaks attire with the following caption: ‘Here’s what you’re defending, black metal purists.