Ten Steps for Implementing a Program of Controlled Substance Testing In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sex Pistols: Punk Rock As Protest Rhetoric

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2002 The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric Cari Elaine Byers University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Byers, Cari Elaine, "The Sex Pistols: Punk rock as protest rhetoric" (2002). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1423. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/yfq8-0mgs This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

“Punk Rock Is My Religion”

“Punk Rock Is My Religion” An Exploration of Straight Edge punk as a Surrogate of Religion. Francis Elizabeth Stewart 1622049 Submitted in fulfilment of the doctoral dissertation requirements of the School of Language, Culture and Religion at the University of Stirling. 2011 Supervisors: Dr Andrew Hass Dr Alison Jasper 1 Acknowledgements A debt of acknowledgement is owned to a number of individuals and companies within both of the two fields of study – academia and the hardcore punk and Straight Edge scenes. Supervisory acknowledgement: Dr Andrew Hass, Dr Alison Jasper. In addition staff and others who read chapters, pieces of work and papers, and commented, discussed or made suggestions: Dr Timothy Fitzgerald, Dr Michael Marten, Dr Ward Blanton and Dr Janet Wordley. Financial acknowledgement: Dr William Marshall and the SLCR, The Panacea Society, AHRC, BSA and SOCREL. J & C Wordley, I & K Stewart, J & E Stewart. Research acknowledgement: Emily Buningham @ ‘England’s Dreaming’ archive, Liverpool John Moore University. Philip Leach @ Media archive for central England. AHRC funded ‘Using Moving Archives in Academic Research’ course 2008 – 2009. The 924 Gilman Street Project in Berkeley CA. Interview acknowledgement: Lauren Stewart, Chloe Erdmann, Nathan Cohen, Shane Becker, Philip Johnston, Alan Stewart, N8xxx, and xEricx for all your help in finding willing participants and arranging interviews. A huge acknowledgement of gratitude to all who took part in interviews, giving of their time, ideas and self so willingly, it will not be forgotten. Acknowledgement and thanks are also given to Judy and Loanne for their welcome in a new country, providing me with a home and showing me around the Bay Area. -

Epidemiological Characteristics of the COVID-19 Spring Outbreak In

Jantzen et al. BMC Infectious Diseases (2021) 21:435 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06002-0 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Epidemiological characteristics of the COVID-19 spring outbreak in Quebec, Canada: a population-based study Rodolphe Jantzen1,2* , Nolwenn Noisel1,2, Sophie Camilleri-Broët3, Catherine Labbé1, Thibault de Malliard1, Yves Payette1 and Philippe Broët1,2,4,5 Abstract Background: By mid-July 2020, more than 108,000 COVID-19 cases had been diagnosed in Canada with more than half in the province of Quebec. In this context, we launched a study to analyze the epidemiological characteristics and the socio-economic impact of the spring outbreak in the population. Method: We conducted an online survey of the participants of the CARTaGENE population-based cohort, composed of middle-aged and older adults. We collected information on socio-demographic, lifestyle, health condition, COVID-19 related symptoms and COVID-19 testing. We studied the association between these factors and two outcomes: the status of having been tested for SARS-CoV-2 and the status of having received a positive test. These associations were measured with univariate and multivariate analyses using a hybrid tree-based regression model. Results: Among the 8,129 respondents from the CARTaGENE cohort, 649 were tested for COVID-19 and 41 were positive. Medical workers and individuals having a contact with a COVID-19 patient had the highest probabilities of being tested (32% and 42.4%, respectively) and of being positive (17.2% and 13.0%, respectively) among those tested. Approximately 8% of the participants declared that they have experienced at least one of the four COVID-19 related symptoms chosen by the Public Health authorities (fever, cough, dyspnea, anosmia) but were not tested. -

Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children David M

Clinical Infectious Diseases IDSA GUIDELINE Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Clinical Practice Guidelines: Diagnosis of Tuberculosis in Adults and Children David M. Lewinsohn,1,a Michael K. Leonard,2,a Philip A. LoBue,3,a David L. Cohn,4 Charles L. Daley,5 Ed Desmond,6 Joseph Keane,7 Deborah A. Lewinsohn,1 Ann M. Loeffler,8 Gerald H. Mazurek,3 Richard J. O’Brien,9 Madhukar Pai,10 Luca Richeldi,11 Max Salfinger,12 Thomas M. Shinnick,3 Timothy R. Sterling,13 David M. Warshauer,14 and Gail L. Woods15 1Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon, 2Emory University School of Medicine and 3Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, 4Denver Public Health Department, Denver, Colorado, 5National Jewish Health and the University of Colorado Denver, and 6California Department of Public Health, Richmond; 7St James’s Hospital, Dublin, Ireland; 8Francis J. Curry International TB Center, San Francisco, California; 9Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics, Geneva, Switzerland; 10McGill University and McGill International TB Centre, Montreal, Canada; 11University of Southampton, United Kingdom; 12National Jewish Health, Denver, Colorado, 13Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Vanderbilt Institute for Global Health, Nashville, Tennessee, 14Wisconsin State Laboratory of Hygiene, Madison, and 15University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock Downloaded from Background. Individuals infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) may develop symptoms and signs of disease (tuber- culosis disease) or may have no clinical evidence of disease (latent tuberculosis infection [LTBI]). Tuberculosis disease is a leading cause of infectious disease morbidity and mortality worldwide, yet many questions related to its diagnosis remain. -

Communication Dialectics in a Musical Community: the Anti- Socialization of Newcomers

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1995 Communication dialectics in a musical community: The anti- socialization of newcomers Karen Louise Rohrbauck-Stout The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rohrbauck-Stout, Karen Louise, "Communication dialectics in a musical community: The anti-socialization of newcomers" (1995). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5411. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5411 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of ^ M O N T A N A Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. * * Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature * * Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature Date Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. COMMUNICATION DIALECTICS IN A MUSICAL COMMUNITY: THE ANTI-SOCIALIZATION OF NEWCOMERS. by Karen Louise Rohrbauck-Stout B .A. the University of Puget Sound, 1992 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 1995 Approved by: Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP40875 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Cooking 401 Book

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Written by: Madonna Weese, Ed. D., Extension Specialist 4-H Youth Development Shirley Camp, MS, RD, Nutrition and Wellness Educator Barbara Farner, MS, Nutrition and Wellness Educator Jananne Finck, MS, RD, Nutrition and Wellness Educator Terri Myers, MA, Project Assistant Kelly Pool, MPA, Youth Development Educator Carol Schlitt, MS, CFCS, Nutrition and Wellness Educator Sarah Todd, MS, RD, Nutrition and Wellness Educator Graphic Design by: Paula Wheeler, www.WheelerArts.com Illustrations with copyright symbol: QuickArt © Wheeler Arts All the recipes in this book were tested by University of Illinois Extension Nutrition and Wellness Educators. • The recipes were analyzed using Food Processor SQL 10.5. • 2% milk was used unless another kind of milk was specified in the recipe. • When a range was given for ingredient amount or number of servings, the largest number was used in the analysis. • When options were listed for ingredients in a recipe, the first ingredient listed was analyzed. Codes for Nutrition Facts: g = gram mg = milligram 2 4-H Cooking 401 © © TABLE OF CONTENTS A Note to Project Helpers . 4 Meat Group . 45 Project Planning Basics . 5 Dry-Heat Cooking: Roasting Meat . 45 Project Record . 6 Moist-Heat Cooking Methods . 55 What Do You Know? . 7 Dried Beans and Peas . 61 Spices and Herbs . 8 Milk Group . 70 Cooking with Spices and Herbs . 8 Ice Cream . 70 Experiment with Spices and Herbs . 10 Experiment with Ice Cream . 72 Custard and Pudding . 75 Celebration Meals . 13 Celebration Meal Planning Checklist . 15 Desserts . 82 Celebration Meal Planning Timeline . 17 Candy . 82 Experiment with Candy . 87 Grain Group . -

Rock What You've Got: Recipes for Preventing Food Waste

2222 22222 2222 66666 2222 222 HAT YOU 22 22 K W ’VE G 22 2 OC OT 22 2 R 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 < 2 < 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 �CIPES2 2 f 2 2 o e2 2 2 2 t r 2 2 2 s 2 2 2 p 2 a 2 2 2 r 2 2 w 2 2 2 2 e 2 2 2 2 2 vKentinL2 g food 2222 22222 2222 66666 2222 222 HAT YOU 22 22 K W ’VE G 22 2 OC OT 22 2 R 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 < 2 < 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 �CIPES2 2 f 2 2 o e2 2 2 2 t r 2 2 2 s 2 2 2 p 2 a 2 2 2 r 2 2 w 2 2 2 2 e 2 2 2 2 2 vKentinL2 g food FO�WORD ddressing food waste in the home is a Love Food Hate Waste Canada is pleased Apriority issue for the National Zero Waste to be contributing some of our recipes and Council, and we applaud the Guelph Family tools to this cookbook, which provides Health Study for creating this cookbook valuable tips to eliminate food waste at as a resource to help Canadian households home. While the statistics on food waste make their food go further and waste less. are troubling, the good news is that tools such as this book offer simple steps to The truth is that Canadian households prevent and reduce food waste that will are wasting more food than they realize. -

Drinking Water Quality in Rural Pennsylvania and the Effect of Management Practices

Drinking Water Quality in Rural Pennsylvania and the Effect of Management Practices Drinking Water Quality in Rural Pennsylvania and the Effect of Management Practices By Bryan R. Swistock, M.S., Stephanie Clemens, M.S. and William E. Sharpe, Ph.D., School of Forest Resources and Institutes of Energy and the Environment, Pennsylvania State University January 2009 This research was sponsored by a grant from the Center for Rural Pennsylvania, a legislative agency of the Pennsylvania General Assembly. The Center for Rural Pennsylvania is a bipartisan, bicameral legislative agency that serves as a resource for rural policy within the Pennsylvania General Assembly. It was created in 1987 under Act 16, the Rural Revitalization Act, to promote and sustain the vitality of Pennsylvania’s rural and small communities. Information contained in this report does not necessarily reflect the views of individual board members or the Center for Rural Pennsylvania. For more information, contact the Center for Rural Pennsylvania, 200 North Third St., Suite 600, Harrisburg, PA 17101, telephone (717) 787-9555, fax (717) 772-3587, email: [email protected]. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Millions of rural and suburban Pennsylvania residents rely on private wells for drinking water, and, each year, 20,000 new wells are drilled. While research has shown that many private wells in the state have failed at least one drinking water standard, Pennsylvania remains one of the few states without any private well regulations. This study was conducted to better understand the prevalence and TABLE OF CONTENTS causes of private well contamination and to evaluate the role of regulatory versus voluntary management of private wells. -

The Berlin Wall: a Simulation for the Social Studies Classroom

Social Education 74(3), pp 152–154 ©2010 National Council for the Social Studies The Berlin Wall: A Simulation for the Social Studies Classroom William B. Russell III ovember 9, 2009, marked the twentieth anniversary of the opening of the period for introduction/painting and one Berlin Wall. The Wall, a symbol of the Cold War, separated the German period for discussion/analysis). It should Npeople for 28 years (1961–1989), keeping those on the East side isolated. be tailored to fit the needs of individual Although the construction and dismantling of the Berlin Wall is a significant part classrooms. Teachers should also refer to of history, the topic is little covered in the classroom. Textbooks generally include their respective state standards, to dis- one sentence on the topic. And yet teaching about the Berlin Wall fits well with the cern how the content covered fits within pedagogical expectations outlined in the national standards created by the National those standards. Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). Procedures Of the 10 thematic strands outlined in 1961 to protect its people from capi- 1. Introduction—As students enter the in these standards, both CULTURE and talism. The wall split Berlin into East classroom, direct each student to a TIME, CONTINUITY, AND CHANGE illustrate and West Berlin. East Berlin was part of specific desk (separate friends and the relevancy of the Berlin Wall to the the socialist state of East Germany (the groups from one another). Once social studies. CULTURE outlines the German Democratic Republic), which students are seated, divide the class importance of examining cultural pat- was created by the Soviet Union. -

Living in Quebec 28

QLWG Skills for Life Acknowledgements Published by: Quebec Literacy Working Group: Central Québec School Board: Patti L. Moore Eastern Shores School Board: Debrah Adams Eastern Townships School Board: Ilze Epners English Montreal School Board: Mario Pasteris and Mary Gouskos Kativik School Board: Carmelle Castonguay Lester B. Pearson School Board: Denise Llewellyn Littoral School Board: David Roberts New Frontiers School Board: Maria Gudzio Riverside School Board: Linda Martin Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board: Darlene Brown Western Québec School Board: Warren Halligan Project Coordinator: Patti L. Moore Author: Vicki-Ann Huegli Project Supervisor: PROCEDE (Provincial Organization of Continuing Education Directors – English) Proofreading: Vérifikation Anglaise: Karen Ingalls Cover Design: Creative Solutions Créatives: Vilnis Epners Additional Expertise: Teachers, Tutors, Students and Local Animators from the following groups who field-tested the units: Central Québec School Board Littoral School Board Chateauguay Valley Literacy Council Lester B. Pearson School Board Eastern Shores School Board New Frontiers School Board Eastern Townships School Board Quebec City Reading Council English Montreal School Board Riverside School Board Gaspesie Literacy Council Sir Wilfrid Laurier School Board Kativik School Board South Shore Reading Council Laurentian Literacy Council Western Quebec Literacy Council The Learning Exchange Western Québec School Board Literacy in Action Yamaska Literacy Council Literacy Unlimited ISBN Number: 978-0-9812349-0-8 © Copyright QLWG Skills for Life Series, 2008 QLWG Skills for Life Series THEMATIC UNITS Competency-based learning meets the needs of all learners. It is important to keep in mind, however, that all learners are different. In order to address the needs and interests of all learners, units have been divided by Essential Life Skills and Individual Life Skills. -

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8Th Edition

GUIDE FOR THE CARE AND USE OF LABORATORY ANIMALS Eighth Edition Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals Institute for Laboratory Animal Research Division on Earth and Life Studies THE NATIONAL ACADEMIES PRESS 500 Fifth Street, NW Washington, DC 20001 NOTICE: The project that is the subject of this report was approved by the Govern- ing Board of the National Research Council, whose members are drawn from the councils of the National Academy of Sciences, the National Academy of Engineer- ing, and the Institute of Medicine. The members of the Committee responsible for the report were chosen for their special competences and with regard for appropriate balance. This study was supported by the Office of Extramural Research, Office of the Direc- tor, National Institutes of Health/Department of Health and Human Services under Contract Number N01-OD-4-2139 Task Order #188; the Office of Research Integrity, Department of Health and Human Services; the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International; American Association for Laboratory Animal Science; Abbott Fund; Pfizer; American College of Laboratory Animal Medicine; Ameri- can Society of Laboratory Animal Practitioners; Association of Primate Veternarians. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this pub- lication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations or agencies that provided support for the project. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the National Institutes of Health, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US government. -

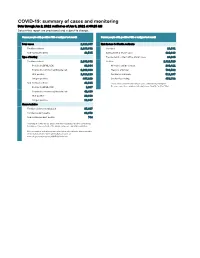

COVID-19: Summary of Cases and Monitoring Data Through Jun 2, 2021 Verified As of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in This Report Are Provisional and Subject to Change

COVID-19: summary of cases and monitoring Data through Jun 2, 2021 verified as of Jun 3, 2021 at 09:25 AM Data in this report are provisional and subject to change. Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Cases: people with positive PCR or antigen test result Total cases 2,329,867 Risk factors for Florida residents 2,286,332 Florida residents 2,286,332 Traveled 18,931 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Contact with a known case 920,896 Type of testing Traveled and contact with a known case 24,985 Florida residents 2,286,332 Neither 1,321,520 Positive by BPHL/CDC 83,364 No travel and no contact 280,411 Positive by commercial/hospital lab 2,202,968 Travel is unknown 733,532 PCR positive 1,819,119 Contact is unknown 511,267 Antigen positive 467,213 Contact is pending 459,732 Non-Florida residents 43,535 Travel can be unknown and contact can be unknown or pending for Positive by BPHL/CDC 1,037 the same case, these numbers will sum to more than the "neither" total. Positive by commercial/hospital lab 42,498 PCR positive 29,688 Antigen positive 13,847 Characteristics Florida residents hospitalized 95,607 Florida resident deaths 36,973 Non-Florida resident deaths 744 Hospitalized counts include anyone who was hospitalized at some point during their illness. It does not reflect the number of people currently hospitalized. More information on deaths identified through death certificate data is available on the National Center for Health Statistics website at www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/COVID19/index.htm.