A Canadian Jew in Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jiddistik Heute

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

Annual Report 2019 / 2020 5

reconciliaction love acknowledgment forgiveness education openness recognition reflection connection love awareness truth respect hope exploration leadership forgiveness communication grace curiosity inspiration education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth reconciliaction caring education humility openness recognition reflection connection recognition reflection curiosity acknowledgment forgiveness love acknowledgment forgiveness love exploration patience communication exploration patience communication ANNUA L caring grace curiosity hope truth REPORT legacy grace curiosity hope truth reconciliaction love humility 2019 - 2020 communication curiosity inspiration grace exploration awareness forgiveness reconciliaction curiosity inspiration grace education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth education respect openness caring Contents Land Acknowledgement ............................................................................................. 3 Message from the Families ......................................................................................... 4 Message from CEO ...................................................................................................... 5 Our Purpose ................................................................................................................ -

You Can't See Me I Am a Stranger…Do You Know What I Mean?

The Stranger I am a stranger…You can't see me I am a stranger…Do you know what I mean? I navigate the mud…I walk above the path Jumpin' to the right…Then I jump to the left On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path nobody knows And what I'm feelin'…Is anyone's guess What is in my head…And what's in my chest I'm not gonna stop…I'm just catching my breath They're not gonna stop…Please just let me catch my breath I am the stranger…You can't see me I am the stranger…Do you know what I mean? That is not my dad…My dad is not a wild man Doesn't even drink…My dad, he's not a wild man On a secret path The one that nobody knows And I'm moving fast On the path that nobody knows I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… I am the stranger… www.downiewenjack.ca Grace, too He said I'm fabulously rich C'mon just let's go She kinda bit her lip Geez, I don't know But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with will and determination And grace, too The secret rules of engagement Are hard to endorse When the appearance of conflict Meets the appearance of force But I can guarantee There'll be no knock on the door I'm total pro That's what I'm here for I come from downtown Born ready for you Armed with skill and it's frustration And grace, too www.downiewenjack.ca Poets Spring starts when a heartbeat's pounding When the birds can be heard Above the reckoning carts doing some final accounting Lava flowing in Superfarmer’s -

Checklist of the Exhibition Checklist of the Exhibition Note: All Objects Are

Checklist of the exhibition Note: All objects are from the collections of the Getty Research Institute, unless otherwise noted. When “photograph” is listed as the medium, the item is a documentary photograph of an original design or artwork. Futurist Beginnings 1. El Lissitzky Cover of Solntse na izlete (Spent sun) Poems by Konstantin Bolshakov Moscow: Tsentrifuga, 1916 88-B24323 2. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Vtoroi sbornik Tsentrifugi (Second Centrifuge collection) Poems by eleven authors Moscow: Tsentrifuga, 1916 90-B4642 3. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Serdtse v perchatke (Heart in a glove) Poems by Konstantin Bolshakov Moscow: Mezonin poezii, 1913 88-B24316 4. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Vetrogradari nad lozami (Gardeners on the vines) Poems by Sergei Bobrov Moscow: Lirika, 1913 88-B24275 1 4a. Natalia Goncharova Pages from Vetrogradari nad lozami (Gardeners on the vines) Poems by Sergei Bobrov Moscow: Lirika, 1913 88-B24275 Yiddish Book Design 5. El Lissitzky Dust jacket from Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 6a. El Lissitzky Cover of Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 6b. El Lissitzky Page from Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 7. El Lissitzky Cover of Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An everyday conversation: A story) Tale by Moses Broderson Moscow: Ferlag Chaver, 1917 93-B15342 8. El Lissitzky Frontispiece from deluxe edition of Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An everyday conversation: A story) Tale by Moses Broderson Moscow: Shamir, 1917 93-B15342 2 9. -

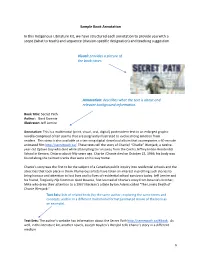

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.1.14 Halifax Regional Council December 12, 2017 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: November 30, 2017 SUBJECT: The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project ORIGIN July 18, 2017 Regional Council Motion: MOVED by Mayor Savage, seconded by Councillor Outhit, that Regional Council request a staff report to: 1. Evaluate the municipality’s potential participation in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project, including through an annual $5,000 contribution for 5 years to the Downie Wenjack Fund; and 2. Evaluate the viability of establishing a Legacy Room within City Hall as a dedicated space for the display of aboriginal art. MOTION PUT AND PASSED UNANIMOUSLY LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Regional Municipality Charter, S.N.S. 2008, c. 39, section 79 (1) The Council may expend money required by the Municipality for … (av) a grant or contribution to … (vii) a registered Canadian charitable organization; RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1. Approve a one-time contribution in the amount of $25,000 from Account M311- Grants and Tax Concession to the Tides Canada Foundation to support cross-cultural reconciliation projects funded under the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund; …RECOMMENDATION CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project Council Report - 2 - December 12, 2017 2. Establish a Downie Wenjack Legacy Room in the Main Floor Boardroom at City Hall as per the terms of the Downie Wenjack Fund; 3. Authorize the Chief Administrative Officer to negotiate and execute an agreement to participate in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project with the Tides Canada Initiatives Society; 4. -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

Residential Schools in Canada: an Education Guide

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map of residential schools in Canada (courtesy of National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, University of Manitoba). Thomas Moore, Regina Indian Industrial School, c. 1874 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/NL-022474). “ When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages, and though he may learn to read and write his habits, and training and mode of thought are Indian. He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed on myself, as the head of the Department, that the Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.” — Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, Official report of the debates of the Table of Contents House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada, 9 May 1883, 1107–1108 Introduction: Residential Schools 2 Introduction: residential schools Message to Teachers 3 Residential schools were government-sponsored religious schools established to assimilate The Legacy of Indigenous children into Euro-Canadian society. Successive Canadian governments used Indian Residential Schools 4 legislation to strip Indigenous peoples of basic human and legal rights, dignity and integrity, Timeline 5 and to gain control over the peoples, their lands and natural rights and resources. The Indian Act, Historical Significance: first introduced in 1876, gave the Canadian government license to control almost every aspect Timeline Activity 8 of Indigenous peoples’ lives. -

Shabbat Program Shabbat Program

SHABBAT PROGRAM SHABBAT PROGRAM Shabbat, August 10 and 11, 2018 / 30 Av 5778 Parashat Re’eh—Rosh Chodesh Elul Night of the Murdered Yiddish Poets �אֵה אָֽנֹכִי נֹתֵן לִפְנֵיכֶם הַיּוֹם בְּ�כָה וּקְלָלָֽה “See this day I set before you blessing and curse.” (Deuteronomy 12:26) 1 Welcome to CBST! ברוכים וברוכות הבאים לקהילת בית שמחת תורה! קהילת בית שמחת תורה מקיימת קשר רב שנים ועמוק עם ישראל, עם הבית הפתוח בירושלים לגאווה ולסובלנות ועם הקהילה הגאה בישראל. אנחנו מזמינים אתכם\ן לגלוּת יהדוּת ליבראלית גם בישראל! מצאו את המידע על קהילות רפורמיות המזמינות אתכם\ן לחגוג את סיפור החיים שלכן\ם בפלאיירים בכניסה. לפרטים נוספים ניתן לפנות לרב נועה סתת [email protected] ©ESTO 2 AUGUST 10, 2018 / 30 AV 5778 PARASHAT RE’EH / ROSH CHODESH ELUL COMMEMORATING THE NIGHT OF THE MURDERED YIDDISH POETS הֲכָנַת הַלֵּב OPENING PRAYERS AND MEDITATIONS *Shabbes Zol Zayn Folk Song שאבעס זאל זיין 36 *(Candle Blessings Abraham Wolf Binder (1895-1967 הַ דְ לָקַת נֵרוֹת שׁ�ל שׁ�בָּת 38 *(Shalom Aleichem Israel Goldfarb (1879-1956 שׁ�לוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם 40 קַבָּלַת שׁ�בָּת KABBALAT SHABBAT / WELCOMING SHABBAT *(L’chu N’ran’nah (Psalm 95) Reuben Sirotkin (Born 1933 לְכוּ נְ�נְּנָה (תהלים צה) 52 *Or Zarua (Psalm 97) Chassidic אוֹר זָ�ֽעַ (תהלים צז) 56 *(Mizmor L’David (Psalm 29) Yiddish Melody (Shnirele Perele מִזְמוֹר לְדָו�ד (תהלים כט) 62 *L'chah Dodi (Shlomo Abie Rotenberg לְכָה דוֹדִ י 66 Alkabetz) Chassidic* *(Tsadik Katamar (Psalm 92) Louis Lewandowski (1821-1894 צַדִּיק כַּתָּמָר (תהלים צב) 72 מַ עֲ �יב MA’ARIV / THE EVENING SERVICE Bar’chu Nusach בָּ�כוּ 78 Hama’ariv Aravim -

Shabbat Program Shabbat Program

SHABBAT PROGRAM SHABBAT PROGRAM August 16 and 17, 2019 / 16 Av 5779 Parashat Vaetchanan Shabbat Nachamu Honoring the Soviet Yiddish Poets נַֽחֲמוּ נַֽחֲמוּ עַמִּי י�אמַר אֱ -הֵיכֶֽם: דַּבְּרוּ עַל־לֵב י�רֽוּשׁ�לַם ו�קִ�אוּ אֵלֶיהָ כִּי מָֽלְאָה צְבָאָהּ כִּי נִ�צָה עֲו�נָהּ כִּי לָֽקְחָה מִיּ�ד ה' כִּפְלַי�ם בְּכָל־חַטֹּאתֶֽיהָ: "Comfort my people, comfort them!" says your God. "Speak tenderly to Jerusalem: say to her that she has served her term, that her sin is pardoned, for she has received from the hand of the Eternal more than enough punishment for her sins.” - (Isaiah 40:1-2) Haftarah for Shabbat Nachamu Welcome to CBST! ברוכים וברוכות הבאים לקהילת בית שמחת תורה! קהילת בית שמחת תורה מקיימת קשר רב שנים ועמוק עם ישראל, עם הבית הפתוח בירושלים לגאווה ולסובלנות ועם הקהילה הגאה בישראל. אנחנו מזמינים אתכם\ן לגלות יהדוּת ליבראלית גם בישראל! מצאו את המידע על קהילות רפורמיות המזמינות אתכם\ן לחגוג את סיפור החיים שלכן\ם בפלאיירים בכניסה. לפרטים נוספים ניתן לפנות לרב נועה סתת: [email protected] 2 AUGUST 16, 2019 / 16 AV 5779 PARASHAT VAETCHANAN – SHABBAT NACHAMU COMMEMORATING THE NIGHT OF THE MURDERED YIDDISH POETS הֲכָנַת הַלֵּב OPENING PRAYERS AND MEDITATIONS *Shabbes Zol Zayn Folk Song שבת זאל זיין 36 (Viglid (Lullaby) Leyb Yampolsky (1889-1972 וויגליד Program with text by Izi Kharik (1898-1937) Candle Lighting Abraham Wolf Binder הַדְלָקַת נֵרוֹת שׁ�ל שׁ�בָּת 38 (1895-1967)* *(Shalom Aleichem Israel Goldfarb (1879-1956 שׁ�לוֹם עֲלֵיכֶם 40 קַבָּלַת שׁ�בָּת KABBALAT SHABBAT / WELCOMING SHABBAT *L’chu N’ran’nah (Psalm 95) Western Sephardic לְכוּ