Residential Schools in Canada: an Education Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

Annual Report 2019 / 2020 5

reconciliaction love acknowledgment forgiveness education openness recognition reflection connection love awareness truth respect hope exploration leadership forgiveness communication grace curiosity inspiration education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth reconciliaction caring education humility openness recognition reflection connection recognition reflection curiosity acknowledgment forgiveness love acknowledgment forgiveness love exploration patience communication exploration patience communication ANNUA L caring grace curiosity hope truth REPORT legacy grace curiosity hope truth reconciliaction love humility 2019 - 2020 communication curiosity inspiration grace exploration awareness forgiveness reconciliaction curiosity inspiration grace education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth education respect openness caring Contents Land Acknowledgement ............................................................................................. 3 Message from the Families ......................................................................................... 4 Message from CEO ...................................................................................................... 5 Our Purpose ................................................................................................................ -

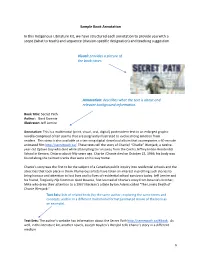

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project

P.O. Box 1749 Halifax, Nova Scotia B3J 3A5 Canada Item No. 14.1.14 Halifax Regional Council December 12, 2017 TO: Mayor Savage and Members of Halifax Regional Council SUBMITTED BY: Jacques Dubé, Chief Administrative Officer DATE: November 30, 2017 SUBJECT: The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project ORIGIN July 18, 2017 Regional Council Motion: MOVED by Mayor Savage, seconded by Councillor Outhit, that Regional Council request a staff report to: 1. Evaluate the municipality’s potential participation in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project, including through an annual $5,000 contribution for 5 years to the Downie Wenjack Fund; and 2. Evaluate the viability of establishing a Legacy Room within City Hall as a dedicated space for the display of aboriginal art. MOTION PUT AND PASSED UNANIMOUSLY LEGISLATIVE AUTHORITY Halifax Regional Municipality Charter, S.N.S. 2008, c. 39, section 79 (1) The Council may expend money required by the Municipality for … (av) a grant or contribution to … (vii) a registered Canadian charitable organization; RECOMMENDATION It is recommended that Halifax Regional Council: 1. Approve a one-time contribution in the amount of $25,000 from Account M311- Grants and Tax Concession to the Tides Canada Foundation to support cross-cultural reconciliation projects funded under the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund; …RECOMMENDATION CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 The Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project Council Report - 2 - December 12, 2017 2. Establish a Downie Wenjack Legacy Room in the Main Floor Boardroom at City Hall as per the terms of the Downie Wenjack Fund; 3. Authorize the Chief Administrative Officer to negotiate and execute an agreement to participate in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Room Project with the Tides Canada Initiatives Society; 4. -

Camera Stylo 2019 Inside Final 9

Moving Forward as a Nation: Chanie Wenjack and Canadian Assimilation of Indigenous Stories ANDALAH ALI Andalah Ali is a fourth year cinema studies and English student. Her primary research interests include mediated representations of death and alterity, horror, flm noir, and psychoanalytic theory. 66 The story of Chanie Wenjack, a 12-year-old Ojibwe boy who froze to death in 1966 while fleeing from Cecilia Jeffery Indian Residential School,1 has taken hold within Canadian arts and culture. In 2016, commemorating the fiftieth anniversary of the young boy’s tragic and lonely death, a group of Canadian artists, including Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, comic book artist Jeff Lemire, and filmmaker Terril Calder, created pieces inspired by the story.2 Giller Prize-winning author Joseph Boyden, too, participated in the commemoration, publishing a novella, Wenjack,3 only a few months before the literary controversy wherein his claims to Indigenous heritage were questioned, and, by many people’s estimation, disproven.4 Earlier the same year, Historica Canada released a Heritage Minute on Wenjack, also written by Boyden.5 Ostensibly, the foregrounding of such a story within a cultural institution as mainstream as the Heritage Minutes functions as a means to critically address Canadian complicity in settler-colonialism. By constituting residential schools as a sealed-off element of history, however, the Heritage Minute instead negates ongoing Canadian culpability in the settler-colonial project. Furthermore, the video’s treatment of landscape mirrors that of the garrison mentality, which is itself a colonial construct. The video deflects from discourses on Indigenous sovereignty or land rights, instead furthering an assimilationist agenda that proposes absorption of Indigenous stories, and people, into the Canadian project of nation-building. -

Indigenous Literature Kit: Growing Our Collective Understanding of Truth and Reconciliation

Indigenous Literature Kit: Growing Our Collective Understanding of Truth and Reconciliation Kindergarten - Grade 12 Billie-Jo Grant, Vincent J Maloney Junior High School Charlotte Kirchner, Vincent J Maloney Junior High School Phyllis Kelly, JJ Nearing Elementary School Nicole Wenger, JJ Nearing Elementary School Rhonda Nixon, Division Office, Deputy Superintendent Yvonne Stang, Division Office, Literacy and ELL Consultant A Collaborative Professional Learning Project Copyright © 2021, 2017 by Greater St. Albert School District (GSACRD), Edmonton Regional Learning Consortium (ERLC), and St. Albert-Sturgeon Regional Collaborative Service Delivery region (RCSD) For more information, contact: Rhonda Nixon, Deputy Superintendent Greater St. Albert Catholic School Division (GSACRD) 6 St. Vital Avenue St. Albert, Alberta T8N 1K2 Ph: 780-459-7711 Yvonne Stang, Literacy and ELL Consultant Greater St. Albert Catholic School Division (GSACRD) 6 St. Vital Avenue St. Albert, Alberta T8N 1K2 Ph: 780-459-7711 2 Acknowledgements This collaborative project began with a mission – to create a professional learning resource that would support educators to grow in their collective understanding of Truth and Reconciliation. In the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action (2012) report, the Canadian government defined “reconciliation” as learning what it means to establish and maintain mutually respectful relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. To that end, there must be awareness of the past, acknowledgement of the harm that has been inflicted, atonement for the causes, and action to change behaviour (pp. 6–7). The TRC presented 94 Calls to Action that outline concrete steps that can be taken to begin the process of reconciliation, and we focused on Education for Reconciliation, 62-65 (pp. -

The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund

Confidential 2021 Competition Final Round The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund May 11, 2021 The Request for Proposals in this document was developed for the Student Evaluation Case Competition for educational purposes. It does not entail any commitment on the part of the Canadian Evaluation Society (CES), the Canadian Evaluation Society Educational Fund (CESEF), The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund, or any related sponsor or service delivery partner. We thank The Gord Downie & Wenjack Fund for graciously agreeing to participate in the final round of the 2021 competition. Thanks to Lisa Prinn, Manager, Education and Activation and Sarah Midanik, President and CEO for their input in preparing this case. The Case Competition is proudly sponsored by: Confidential Introduction Congratulations to all three teams for qualifying for the Final Round of the 2021 CES/CESEF Student Evaluation Case Competition! Your consulting firm has been invited to respond to the attached Request for Proposals (RFP) issued by The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) to tell the story of how DWF’s activities have contributed to positive impacts on the lives of Indigenous Peoples in Canada. The charity, supported by an advisory group of external evaluation experts, has requested a briefing from each firm on their proposal. Your proposal should demonstrate your understanding of the assignment and include a logic model, a proposed methodology, an evaluation matrix, a mitigation strategy to address anticipated evaluation challenges and a discussion of an evaluation competency that is important for a successful evaluation of this organization.1 Section 2.2 of the RFP identifies the proposal requirements in more detail. -

GV-March 18-Secondary

VOLUME 11 | ISSUE 23 A ROOM OF HIS OWN: THE LEGACY OF CHANIE WENJACK SECONDARY RESOURCES gNOTE TO EDUCATORS g The following activities are designed to stimulate a current events discussion. Generative in nature, these questions can be a launching point for additional assignments or research projects. Teachers are encouraged to adapt these activities to meet the contextual needs of their classroom. In some cases, reading the article with students may be appropriate, coupled with reviewing the information sheet to further explore the concepts and contexts being discussed. From here, teachers can select from the questions provided below. The activity is structured to introduce students to the issues, then allow them to explore and apply their A length of railway track evokes the tragic journey of Chanie Wenjack in this ‘Legacy Room’ created by learnings. Students are encouraged to further landscaping company Genoscape at the Canada Blooms national garden show. (Photo credit: McNeill reflect on the issues. Photography) BACKGROUND INFORMATION schools in Manitoba and the Northwest Core Skill Sets: Territories in 1907, he found serious health These icons identify the most relevant core • In 1883, the federal government of Prime problems and widespread disease skills students will develop using this resource. Minister Sir John A. MacDonald passed a throughout a majority of schools. (Bryce: Learn more about the WE Learning Framework law to officially establish a system of Report on the Indian Schools of Manitoba at www.WE.org/we-at-school/we-schools/ residential schools. One of MacDonald’s and the North-west Territories) learning-framework/. ministers, Hector Langevin is quoted as saying: “In order to educate the children • The estimated number of children who properly we must separate them from died in residential schools is now more KEY TERMS their families. -

Gord Downie 1964-2017

Levels 1 & 2 (grades 5 and up) Gord Downie 1964-2017 Article page 2 Questions page 4 Photo page 6 Crossword page 7 Quiz page 8 Breaking news november 2017 A monthly current events resource for Canadian classrooms Routing Slip: (please circulate) National Farewell, Gord Downie – And thank you for the music Th e country was united in sorrow on “If you’re a musician and you’re born “I thought I was going to make it October 17 when singer-songwriter in Canada it’s in your DNA to like through this but I’m not,” the prime Gord Downie died of terminal brain the Tragically Hip,” said Canadian minister said. His voice broke and cancer. He was 53. Mr. Downie was musician Dallas Green. he cried openly. “We all knew it was the front man of Th e Tragically Hip, coming,” Mr. Trudeau said. “But His last great concerts arguably the nation’s most beloved we hoped it wasn’t. We are less as a rock band. Th e band played a series of concerts country without Gordon Downie.” across Canada last summer. Th e CBC “Gord knew this day was coming,” Another fan, Melanie Wells, paid her carried the last show in Kingston. Th e his family wrote on his website. “His respects to Mr. Downie at a day-long broadcast aired in pubs, parks, and response was to spend this precious memorial held in Kingston. “It’s a drive-in movie theatres across the time as he always had – making music, band that’s been with me my whole country. -

Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project 2018-2019

North Vancouver School District Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project 2018-2019 The North Vancouver School District is very honoured to have five schools selected to be part of the Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project. The five schools are École Windsor Secondary, Norgate-Xwemélch’stn, Ns7e’yxnitm la Tel:’wet Westview, Carisbrooke and École Sherwood Park. The Secret Path is an album that began as 10 poems written by Gord Downie from the Tragically Hip, after learning about the death of Chanie Wenjack, who died on October 22, 1966, while trying to get home after fleeing from Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School. The poems later became the basis of an album which was illustrated by Jeff Lemire. You can find out more about the Secret Path here The Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project is a program that provides “opportunity for classrooms/schools to lead the movement in awareness of the history and impact of the Residential School System on Indigenous Peoples” (downiewenjack.ca). Schools/classes participating in the Downie Wenjack Legacy Project are encouraged to create a ReconcilliACTIONs which is representative of their school and community. You can learn more about the Downie Wenjack Legacy Project here . Chanie Wenjack 1 The Downie Wenjack Legacy Schools Project began with a guest presentation by Mike Downie on behalf of the Downie Wenjack organization, at Norgate-Xwemélch’stn, on October 4, 2018. NVSD representatives from all five Legacy schools were in attendance. Participating schools received a Legacy Schools Toolkit and educational support andresources to share with staff and students. -

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS in CANADA History and Legacy

RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS IN CANADA History and Legacy A project of With support from This education guide Introduction: residential schools is based on Historica Canada’s 2016 Residential schools were government-sponsored Christian schools established to assimilate Indigenous children into settler-Canadian society. Successive Canadian governments used legislation to strip Residential Schools in Indigenous peoples of their basic human and legal rights and to gain control over Indigenous lives, Canada Education Guide. their lands, and natural rights and resources. The Indian Act, first introduced in 1876, gave the Canadian The guide was developed government licence to control almost every aspect of First Nations peoples’ lives. Amendments to the in collaboration and Act later required children to attend residential schools, the majority of which operated after 1880. These consultation with policies were applied inconsistently to Métis and Inuit communities. educators, academics, One of the main goals of these schools was to assimilate Indigenous peoples into Canadian society and community through a process of cultural, social, educational, economic, political, and religious assimilation, achieved stakeholders, including through removing and isolating Indigenous children from their homes, families, lands, and cultures. This Holly Richard, Dr. Tricia goal was based on the false assumption that Indigenous cultures and Indigenous spiritual beliefs were Logan, Dr. Crystal Gail inferior to those of white Euro-Canadians. Assimilation policies, including education policies, ultimately Fraser, Amos Key Jr., aimed to undermine Indigenous rights. Dr. John Milloy, and Kenneth Campbell. Residential schools were underfunded and overcrowded; they were rife with starvation, disease, and neglect. Children were often isolated from human contact and nurturing, and many experienced rampant physical, emotional, and sexual abuse. -

Mike Downie Introduced Me to Chanie Wenjack

Mike Downie introduced me to Chanie Wenjack; he gave me the story from Ian Adams’ Maclean’s magazine story dating back to February 6, 1967, “The Lonely Death of Charlie Wenjack.” Chanie, misnamed Charlie by his teachers, was a young boy who died on October 22, 1966, walking the railroad tracks, trying to escape from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School to walk home. Chanie’s home was 400 miles away. He didn’t know that. He didn’t know where it was, nor how to find it, but, like so many kids - more than anyone will be able to imagine - he tried. I never knew Chanie, but I will always love him. Chanie haunts me. His story is Canada’s story. This is about Canada. We are not the country we thought we were. History will be re-written. We are all accountable, but this begins in the late 1800s and goes to 1996. “White” Canada knew – on somebody’s purpose – nothing about this. We weren’t taught it in school; it was hardly ever mentioned. All of those Governments, and all of those Churches, for all of those years, misused themselves. They hurt many children. They broke up many families. They erased entire communities. It will take seven generations to fix this. Seven. Seven is not arbitrary. This is far from over. Things up north have never been harder. Canada is not Canada. We are not the country we think we are. I am trying in this small way to help spread what Murray Sinclair said, “This is not an aboriginal problem.