RESIDENTIAL SCHOOLS in CANADA History and Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Factum Majority (55%) of Canadians – Both Women (59%) and Men (52%) – Fail True-Or-False Quiz About Canadian Women’S History

Factum Majority (55%) of Canadians – Both Women (59%) and Men (52%) – Fail True-or-False Quiz about Canadian Women’s History Celine Dion Tops the List of Canadian Women that Canadians Most Want to Dine With Toronto, ON, October XX, 2018 — A majority (55%) of Canadians have failed a true-or-false quiz about Canadian women’s history, according to a new Ipsos poll conducted on behalf of Historica Canada. Only 45% of Canadians scored at least 6 correct responses out of 12 to pass the quiz, which covered questions relating to political history, arts and culture, and military history. More specifically, just 3% of Canadians got an “A”, answering 10 or more questions correctly. Another 5% got a “B” (9 questions correct), 9% a “C” (8 questions correct), and 27% a D. In fact, a majority of both women (59%) and men (52%) failed the quiz. The fail rate was highest in Alberta (62%), followed by those living in British Columbia (57%), Ontario (56%), Quebec (56%), Saskatchewan and Manitoba (45%) and Atlantic Canada (45%). In Saskatchewan and Manitoba and Atlantic Canada, a majority (55%) passed the twelve-question quiz. Six in ten individuals aged 18-34 (59%) and 35-54 (61%) failed, while only 48% of Boomers aged 55+ failed. The following chart displays the statements that were posed to Canadians, along with the percentage who believed them to be true, false, or simply didn’t know and didn’t venture a guess. The correct answer is bolded, and results are displayed from the most accurate to the least accurate. -

Legacy Schools Reconciliaction Guide Contents

Legacy Schools ReconciliACTION Guide Contents 3 INTRODUCTION 4 WELCOME TO THE LEGACY SCHOOLS PROGRAM 5 LEGACY SCHOOLS COMMITMENT 6 BACKGROUND 10 RECONCILIACTIONS 12 SECRET PATH WEEK 13 FUNDRAISING 15 MEDIA & SOCIAL MEDIA A Message from the Families Chi miigwetch, thank you, to everyone who has supported the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund. When our families embarked upon this journey, we never imagined the potential for Gord’s telling of Chanie’s story to create a national movement that could further reconciliation and help to build a better Canada. We truly believe it’s so important for all Canadians to understand the true history of Indigenous people in Canada; including the horrific truths of what happened in the residential school system, and the strength and resilience of Indigenous culture and peoples. It’s incredible to reflect upon the beautiful gifts both Chanie & Gord were able to leave us with. On behalf of both the Downie & Wenjack families -- Chi miigwetch, thank you for joining us on this path. We are stronger together. In Unity, MIKE DOWNIE & HARRIET VISITOR Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund 3 Introduction The Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) is part of Gord Downie’s legacy and embodies his commitment, and that of his family, to improving the lives of Indigenous peoples in Canada. In collaboration with the Wenjack family, the goal of the Fund is to continue the conversation that began with Chanie Wenjack’s residential school story, and to aid our collective reconciliation journey through a combination of awareness, education and connection. Our Mission Inspired by Chanie’s story and Gord’s call to action to build a better Canada, the Gord Downie & Chanie Wenjack Fund (DWF) aims to build cultural understanding and create a path toward reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. -

A Project Of: with Support From

A Project of: With support from: Part II: MESSAGE INTRODUCTION In your original small groups, look at documents such CANADA’S SYSTEM A healthy democratic society functions best when its population as the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, is educated and engaged as active and informed citizens. Civics Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s study education equips ordinary citizens with knowledge of how the guide for newcomers, and the Welcome to Canada guide, Canadians elect Parliaments in every federal and provincial This guide complements provincial Canadian political system works, and empowers them to make a all of which are available online. Write down at least three election, as well as in the Yukon territory. The party that has and territorial curricula in middle difference in their communities and beyond. values from the Charter. Give examples from the other the most seats in Parliament is given the constitutional right and high school civics and social documents of statements that reflect these values in to form the government. This is known as “commanding the science classes and is meant to This education guide focuses on key topics in Canadian support of your findings. confidence of the House.” The leader of the party that forms civics. The activities inform readers about how the Canadian help prepare students for the the government becomes the prime minister in a federal governmental system works, and their rights and responsibilities In small groups or in a class discussion, compare your five Citizenship Challenge. The lessons election or the premier in a provincial election. may be used in order or on their as Canadian citizens. -

Downloaded from the Historica 8E79-6Cf049291510)

Petroglyphs in Writing-On- “Language has always LANGUAGE POLICY & Stone Provincial 1774 Park, Alberta, The Quebec Act is passed by the British parliament. To Message been, and remains, RELATIONS IN CANADA: (Dreamstime.com/ TIMELINE Photawa/12622594). maintain the support of the French-speaking majority to Teachers at the heart of the in Québec, the act preserves freedom of religion and canadian experience.” reinstates French civil law. Demands from the English This guide is an introduction to the Official Languages Graham Fraser, minority that only English-speaking Protestants could Act and the history of language policy in Canada, and Time immemorial vote or hold office are rejected. former Commissioner is not exhaustive in its coverage. The guide focuses An estimated 300 to 450 languages are spoken of Official Languages primarily on the Act itself, the factors that led to its Flags of Québec and La Francophonie, 2018 by Indigenous peoples living in what will become (2006-2016) (Dreamstime.com/Jerome Cid/142899004). creation, and its impact and legacy. It touches on key modern Canada. The Mitred Minuet (courtesy moments in the history of linguistic policy in Canada, Library and though teachers may wish to address topics covered 1497 Archives inguistic plurality is a cornerstone of modern Canadian identity, but the history of language in Canada/ e011156641). in Section 1 in greater detail to provide a deeper Canada is not a simple story. Today, English and French enjoy equal status in Canada, although John Cabot lands somewhere in Newfoundland or understanding of the complex nature of language Lthis has not always been the case. -

Annual Report 2019 / 2020 5

reconciliaction love acknowledgment forgiveness education openness recognition reflection connection love awareness truth respect hope exploration leadership forgiveness communication grace curiosity inspiration education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth reconciliaction caring education humility openness recognition reflection connection recognition reflection curiosity acknowledgment forgiveness love acknowledgment forgiveness love exploration patience communication exploration patience communication ANNUA L caring grace curiosity hope truth REPORT legacy grace curiosity hope truth reconciliaction love humility 2019 - 2020 communication curiosity inspiration grace exploration awareness forgiveness reconciliaction curiosity inspiration grace education legacy reconciliaction respect truth understanding compassion acknowledgment education reconciliaction love forgiveness respect awareness connection inspiration truth education respect openness caring Contents Land Acknowledgement ............................................................................................. 3 Message from the Families ......................................................................................... 4 Message from CEO ...................................................................................................... 5 Our Purpose ................................................................................................................ -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

Theme: Cultures Within Us and Around Us

Imagine Culture Teaching Tools: Senior These tools are designed to support submissions to the Passages Canada Imagine Culture Contest – Senior category (Grades 10 to 12 / Secondary IV-V in Quebec). Submissions must address the theme below. Passages Canada speakers can be invited free of charge to speak to your class, as an accompaniment to these resources, by completing the “Invite a Speaker” form on our website. The rubrics that will be used to judge submissions can be found in the appendices. Guidelines: • Photograph submissions must include a brief caption written by the student describing the piece and how it relates to the theme (no more than 200 words). Photograph must be submitted as a .jpeg or .png file. Video is not accepted at this time. See Rules and Regulations for guidelines regarding photo permissions and other details. Prizes: • The best student entry will be awarded a new iPad. The 2nd place entry will be awarded a digital camera (approx. value $250), and the 3rd place entry will win a $100 gift card to Henry’s Camera Store. Full contest details are available at http://passagestocanada.com/imagine-culture- contest/ Theme: Cultures within us and around us. Snap a photo that explores the cultural traditions in your family, school, or community. Tell us your image’s story in a short caption. Think about your favourite food, a treasured object, a family photo album, buildings in your neighbourhood, local festivals; or even just look in the mirror– what stories of cultural heritage are told by these people, places and things? Think about the following: • How do we express culture in our daily lives here in Canada? What examples can you come up with of the ways that your family, school or community expresses their cultural traditions? • Have you shared in someone else’s culture or traditions? Tell us about that experience. -

The Fenian Raids

Students may require some additional background to fully understand the context of the Fenian Raids. Much of the history of the Fenians can be traced to message to teachers the complex relationship between Ireland and Britain. The Fenians were part of Historica Canada has created this Education Guide to mark the an Irish republican revolutionary tradition of resisting British rule that dates back sesquicentennial of the Fenian Raids, and to help students to the 18th century. Many Irish people blamed British government policy for the explore this early chapter in Canada’s history. systematic socioeconomic depression and the Great Famine of the late 1840s and The Fenian Raids have not figured prominently in Canadian history, but they are early 1850s. As a result of the massive death toll from starvation and disease, and often cited as an important factor in Confederation. Using the concepts created the emigration that followed, the fight for Irish independence gathered by Dr. Peter Seixas and the Historical Thinking Project, this Guide complements momentum on both sides of the Atlantic. Canadian middle-school and high-school curricula. It invites students to deepen This Guide was produced with the generous support of the Government of their understanding of the wider context in which Confederation took place through Canada. Historica Canada is the largest organization dedicated to enhancing research and analysis, engaging discussion questions, and group activities. awareness of Canada’s history and citizenship. Additional free bilingual The Fenian Raids represent an intersection of Canadian, Irish, American and British educational activities and resources are available in the Fenian Raids Collection history. -

Download This Page As A

Historica Canada Education Portal Inukshuk Overview This lesson is based on viewing the Inukshuk Heritage Minute, which depicts an RCMP officer watching a group of Inuit build an Inukshuk in the year 1931. Aims Students will learn about the "traditional" Inuit way of life and cultural expression. These activities are intended to give students an appreciation and understanding of the Inuit culture and "traditional" way of life, as well as an understanding of how new technologies might alter Inuit culture. Activities 1. Looking at the Minute Watch the Minute for clues about Inuit life. - After reading the account of Inuit life and watching the Minute, speculate about what the Inuit family is doing? During what season does the Minute take place? Describe the location. What might the family be doing at that site? What signs are there that the Inuit and European Canadians have been in contact with each other for some time? - Look closely at the clothes the Inuit characters are wearing. What do you think they are made of? Is there any evidence of skill in their workmanship or of artistry in their decoration? How does the Minute reinforce the article's statement about Inuit social life? 2. Cultural expression Inuit prints and sculpture have become famous throughout the world for their beauty and their expressiveness. - Collect examples of Inuit art from books and magazines. Discuss the many ways the artwork reflects the traditional life of the Inuit, as well as the impact of "Southern" culture on that tradition. - Have students do some research about Inuit myths and spiritual beliefs. -

Privacy Policy, Our Information Systems and Train All Personnel Accordingly

Historica Canada Privacy Statement WE VALUE YOUR PRIVACY Any personal information gathered by Historica Canada (“Historica”, “we”) will only be used by Historica, its affiliates, or any organization authorized by Historica, in a manner consistent with the implementation of policies and procedures in the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). Historica will conduct itself, in all areas of ongoing business and operations in a manner which will protect all personal information collected, stored and used in such activities in a manner consistent with the mandate of PIPEDA. 1. Objective and scope of policy Historica is committed to respecting your privacy and has prepared this Policy Statement to inform you of our policy and practices concerning the collection, use and disclosure of your personal information. This Policy Statement governs personal information collected from and about individuals who are or may become customers and those other individuals or partners with whom we work. It does not govern personal information that Historica collects from and about our employees, the protection of which is governed by other Historica policies. This Policy Statement also governs how Historica treats personal information in connection with your use of an Historica web site. Using contractual or other arrangements, Historica shall ensure that agents, contractors or third party service providers, who may receive personal information in the course of providing services to Historica as part of our delivery of products and services, protect that personal information in a manner consistent with the principles articulated in this Policy Statement. In the event of questions about: (i) access to your personal information; (ii) Historica's collection, use, management or disclosure of personal information; or (iii) this Policy Statement; please contact: Historica Canada 2 Carlton Street, East Mezzanine Toronto, ON, M5B 1J3 Attn: Privacy Officer [email protected] 2. -

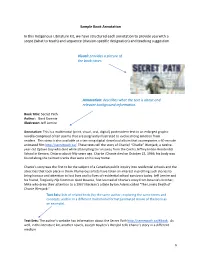

6 Sample Book Annotation in This Indigenous Literature Kit, We Have Structured Each Annotation to Provide You with a Scope

Sample Book Annotation In this Indigenous Literature Kit, we have structured each annotation to provide you with a scope (what to teach) and sequence (division-specific designation) and teaching suggestion. Visual: provides a picture of the book cover. Annotation: describes what the text is about and relevant background information. Book Title: Secret Path Author: Gord Downie Illustrator: Jeff Lemire Annotation: This is a multimodal (print, visual, oral, digital) postmodern text in an enlarged graphic novella comprised of ten poems that are poignantly illustrated to evoke strong emotion from readers. This story is also available as a ten-song digital download album that accompanies a 60-minute animated film http://secretpath.ca/. These texts tell the story of Chanie/ “Charlie” Wenjack, a twelve- year-old Ojibwe boy who died while attempting to run away from the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School in Kenora, Ontario about fifty years ago. Charlie /Chanie died on October 22, 1966; his body was found along the railroad tracks that were on his way home. Chanie’s story was the first to be the subject of a Canadian public inquiry into residential schools and the atrocities that took place in them. Numerous artists have taken an interest in profiling such stories to bring honour and attention to lost lives and to lives of residential school survivors today. Jeff Lemire and his friend, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie, first learned of Chanie's story from Downie's brother, Mike who drew their attention to a 1967 Maclean's article by Ian Adams called "The Lonely Death of Chanie Wenjack." Text Sets: lists of related texts (by the same author; exploring the same terms and concepts; and/or in a different multimodal format (animated movie of the book as an example). -

Canada History Week 2018 Science, Creativity and Innovation: Our Canadian Story

Highlights 04. 06. 09. What is Canada History Week? Canada History Week provides Canadians throughout the country with opportunities to learn more about the people and events that have shaped the great nation that we know today. Canada is full of unique people, places and events. Canada History Week is a great time to discover them! Past themes included: • In 2014, Canada History Week had a different theme each day: Discovering our National Museums, Discovering our Historic Sites, and more; • In 2015, the theme was Sport through History which connected with the Year of Sport in Canada; • In 2016, the theme was the 100th anniversary of women’s first right to vote in Canada, and great women in Canadian history; • In 2017, the theme was “Human Rights in Canada: Challenges and Achievements on the Path to a More Inclusive and Compassionate Society.” Canada History Week 2018 Science, Creativity and Innovation: Our Canadian Story The week will highlight historic achievements by Canadians in the fields of medicine, science, technology, engineering, and math. Canada History Week is one great way to highlight the importance of the past in guiding our civic and public participation. We hope you will take a bit of time this week to learn and think about the ways science and technology are transforming your everyday life. Want to share online? Post photos, videos and messages and take part in the discussion using the hashtag #HistoryWeek2018 #HistoryWeek2018 For many years scientists believed that some kind of internal secretion of the pancreas was the key to preventing diabetes and controlling normal metabolism.