A Documentary Reconstruction of Edmonton's Rock Cirkus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-688

Broadcasting Decision CRTC 2012-688 PDF version Route reference: 2012-475 Ottawa, 19 December 2012 Touch Canada Broadcasting (2006) Inc. (the general partner) and C.R.A. Investments Ltd. (the limited partner), carrying on business as Touch Canada Broadcasting Limited Partnership Edmonton, Calgary and Red Deer, Alberta Application 2012-0642-5, received 24 May 2012 Public hearing in the National Capital Region 7 November 2012 CJCA and CJRY-FM Edmonton, CJLI and CJSI-FM Calgary and CKRD-FM Red Deer – Acquisition of assets (corporate reorganization) 1. The Commission approves the application by Touch Canada Broadcasting (2006) Inc. (the general partner) and C.R.A. Investments Ltd. (the limited partner), carrying on business as Touch Canada Broadcasting Limited Partnership (Touch Canada LP), for authorization to effect a two-step corporate reorganization involving the assets of the radio programming undertakings CJCA and CJRY-FM Edmonton, CJLI and CJSI-FM Calgary and CKRD-FM Red Deer. 2. Touch Canada Broadcasting (2006) Inc. and C.R.A. Investments Ltd. (CRA) are both controlled by Charles R. Allard. 3. The Commission did not receive any interventions in connection with this application. 4. The proposed corporate reorganization will be executed as follows: Step 1 • Transfer to CRA of all Class A voting shares issued by Touch Canada Broadcasting Inc. (TCBI), the current limited partner in Touch Canada LP and a corporation also owned and controlled by Mr. Allard. As a result, TCBI will become wholly owned by CRA. Step 2 • Wind up of TCBI. The 99.89% voting units held by TCBI in Touch Canada LP will be transferred to CRA. -

Approach to Community Recreation Facility Planning in Edmonton

Approach to Community Recreation Facility Planning In Edmonton Current State of Community and Recreation Facilities Report April 2018 CR_5746 Attachment 3 CR_5746 Attachment 3 Table of Contents 1: Introduction 1 Project Overview and Methodology 1 2: Summary of the 2005 – 2015 Recreation Facility Master Plan 3 Overview of the 2005 – 2015 RFMP 3 2009 RFMP Update 6 Additional Plans Emanating from the 2005 – 2015 RFMP & 2009 Update 7 Infrastructure Milestones 9 3: Community Dynamics 13 Historical Growth Overview 14 Demographics Profile 15 Social Vulnerability 19 Current Population Distribution 21 Anticipated Growth 21 Regional Growth 22 4: Provincial and National Planning Influences 23 A Framework for Recreation in Canada 2015: Pathways to Wellbeing 24 Active Alberta Policy 26 Going the Distance: The Alberta Sport Plan (2014-2024) 27 Canadian Sport for Life 28 Truth and Reconciliation 29 The Modernized Municipal Government Act 30 Alignment with the New Vision and Goals 31 5: Strategic Planning of Key Partners 32 Partnership Approach Overview 33 6: Strategic Planning of other Capital Region Municipalities 35 Regional Infrastructure Overview 36 Strategic Planning and Potential Initiatives 37 Capital Region Board Planning 41 CR_5746 Attachment 3 Table of Contents 7: Leading Practices and Trends: Recreation 42 General Trends in Recreation 43 Physical Activity and Wellness Levels 43 Participation Trends 44 Recreation Activity Shifts 47 Understanding the Recreation Facility Consumer in Edmonton 50 Market Share 50 Summary of Market Share Position -

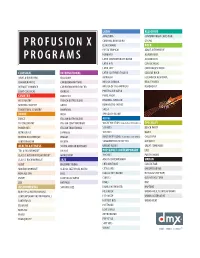

Profusion X Programs

LATIN RELIGIOUS AMAZONIA CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN CARNIVAL BRASILEIRO GOSPEL PROFUSION X EL MOCAMBO ROCK FIESTA TROPICAL ADULT ALTERNATIVE HURBANO ALBUM ROCK PROGRAMS LATIN CONTEMPORARY BLEND ALTERNATIVE LATIN HITS CLASSIC ROCK LATIN JAZZ COFFEEHOUSE ROCK CLASSICAL INTERNATIONAL LATIN SOUTHWEST BLEND COLLEGE ROCK ARIAS & OVERTURES BELLISIMA MARIACHI FLASHBACK NEW WAVE CHAMBER MUSIC CARIBBEAN RHYTHMS MÚSICA CUBANA REALITY BITES INTIMATE CHAMBER CARIBBEAN WORLD BLEND MÚSICA DE LAS AMERICAS ROADHOUSE LIGHT CLASSICAL CHINESE PORTUGLISH BLEND COUNTRY EURO HITS PURO AMOR HIT COUNTRY FRENCH BISTRO BLEND REGIONAL MEXICAN MODERN COUNTRY GREEK ROMANCERO LATINO TRADITIONAL COUNTRY HAWAIIAN SALSA DANCE IRISH SPANGLISH BLEND DANCE ITALIAN BISTRO BLEND OLDIES ELECTROSPHERE ITALIAN CONTEMPORARY ‘60S REVOLUTION formerly Rock ‘N’ Roll Oldies) SPECIALTY POWER HITS ITALIAN TRADITIONAL ’70S HITS BEACH PARTY RETRO DISCO JAPANESE ’80S HITS BLUES RIVIERA DISCOTHÈQUE REGGAE MALT SHOP OLDIES formerly Golden Oldies) CHILLTOPIA SUBTERRANEAN RIVIERA SONGWRITERS OF THE ‘70S GOT KIDS? HEALTH & FITNESS SOUTH AFRICAN RHYTHMS UPBEAT OLDIES GREAT STANDARDS ’70S & ’80S WORKOUT UK HITS POP/ADULT CONTEMPORARY LOL! CLASSIC ALTERNATIVE WORKOUT WORLD BEAT ’90S HITS PARTY FAVORS CLASSIC ROCK WORKOUT JAZZ ADULT CONTEMPORARY URBAN GLOW BIG BAND SWING CHÍC BOUTIQUE CLASSIC R&B MODERN WORKOUT CLASSIC JAZZ VOCAL BLEND CITYSCAPES GROOVE LOUNGE NEW AGE SPA JAZZ CLASSIC HITS BLEND HOT JAMZ HIP HOP PUMP! JAZZ VOCAL BLEND CLUB 12 OLD SCHOOL FUNK ZEN RAT PACK DIVAS RAP INSTRUMENTAL SMOOTH -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. January 13, 2020 to Sun. January 19, 2020

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. January 13, 2020 to Sun. January 19, 2020 Monday January 13, 2020 4:00 PM ET / 1:00 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT The Top Ten Revealed Tom Green Live Epic Songs of ‘73 - Find out which epic songs of ‘73 make our list as rock experts like Eddie Andrew Dice Clay - It’s a reunion of the true bad boys of comedy as actor and legendary stand-up Money, Lita Ford, Clem Burke (Blondie), Caleb Quaye (Elton John) and Jack Russell (Jack Russell’s comedian Andrew Dice Clay reconnects with his running mate Tom for a no-holds-barred discus- Great White) count us down! sion of life, show-biz, and whatever else pops up. 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT The Day The Rock Star Died Classic Albums Michael Jackson - Michael Jackson was a singer, songwriter, dancer and known simply as “The Phil Collins: Face Value - The program includes several previously unseen performances as well as King of Pop.” His contributions to music, dance, and highly publicized personal life made him a rare home movies of the studio sessions where Phil Collins worked closely with Hugh Padgham global figure in popular culture for over four decades. and the Earth, Wind & Fire horn section. Featuring the classic ‘In The Air Tonight,’ ‘Behind The Lines,’ ‘Please Don’t Ask,’ ‘I Missed Again’ and ‘This Must Be Love.’ 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT The Ronnie Wood Show 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Bobby Gillespie - Joining Ronnie this week is lead singer and founding member of Primal Rock Legends Scream, Scottish-born Bobby Gillespie. -

Serbia Turns Blind Eye to Rare Bird Slaughter

Issue No. 211 Friday, July 22 - Thursday, September 08, 2016 ORDER DELIVERY TO Belgrade ‘failing to Political Must-see YOUR DOOR +381 11 4030 303 develop satirists eye music [email protected] - - - - - - - ISSN 1820-8339 1 mid-market Belgrade local festivals BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY 0 1 tourism’ elections in August Page 5 Page 9 Page 13 9 7 7 1 8 2 0 8 3 3 0 0 0 Even when the Democrats longas continue to likely is This also are negotiations Drawn-out Surely the situation is urgent Many of us who have experi We feel in-the-know because bia has shown us that (a.) no single no (a.) that us shown has bia party or coalition will ever gain the governa form to required majority negotiations political (b.) and ment, will never be quickly concluded. achieved their surprising result at last month’s general election, quickly itbecame clear that the re sult was actually more-or-less the result election other every as same in Serbia, i.e. inconclusive. as Serbia’s politicians form new political parties every time disagree with they their current party reg 342 currently are (there leader political parties in Serbia). istered the norm. One Ambassador Belgrade-based recently told me he was also alarmed by the distinct lack of urgency among politicians. Serbian “The country is standstill at and a I don’t understand their logic. If they are so eager to progress towards the EU and en theycome how investors, courage go home at 5pm sharp and don’t work weekends?” overtime. -

Stu Davis: Canada's Cowboy Troubadour

Stu Davis: Canada’s Cowboy Troubadour by Brock Silversides Stu Davis was an immense presence on Western Canada’s country music scene from the late 1930s to the late 1960s. His is a name no longer well-known, even though he was continually on the radio and television waves regionally and nationally for more than a quarter century. In addition, he released twenty-three singles, twenty albums, and published four folios of songs: a multi-layered creative output unmatched by most of his contemporaries. Born David Stewart, he was the youngest son of Alex Stewart and Magdelena Fawns. They had emigrated from Scotland to Saskatchewan in 1909, homesteading on Twp. 13, Range 15, west of the 2nd Meridian.1 This was in the middle of the great Regina Plain, near the town of Francis. The Stewarts Sales card for Stu Davis (Montreal: RCA Victor Co. Ltd.) 1948 Library & Archives Canada Brock Silversides ([email protected]) is Director of the University of Toronto Media Commons. 1. Census of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta 1916, Saskatchewan, District 31 Weyburn, Subdistrict 22, Township 13 Range 15, W2M, Schedule No. 1, 3. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. CAML REVIEW / REVUE DE L’ACBM 47, NO. 2-3 (AUGUST-NOVEMBER / AOÛT-NOVEMBRE 2019) PAGE 27 managed to keep the farm going for more than a decade, but only marginally. In 1920 they moved into Regina where Alex found employment as a gardener, then as a teamster for the City of Regina Parks Board. The family moved frequently: city directories show them at 1400 Rae Street (1921), 1367 Lorne North (1923), 929 Edgar Street (1924-1929), 1202 Elliott Street (1933-1936), 1265 Scarth Street for the remainder of the 1930s, and 1178 Cameron Street through the war years.2 Through these moves the family kept a hand in farming, with a small farm 12 kilometres northwest of the city near the hamlet of Boggy Creek, a stone’s throw from the scenic Qu’Appelle Valley. -

1. CROSS-BORDER REGION „KRŠ “ (Introductory Remarks)

KRSH Preparation for implementation of the Area Based Development (ABD) Approach in the Western Balkans BASELINE STUDY AND STRATEGIC PLAN FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE CROSS-BORDER REGION “KRŠ” BASELINE STUDY AND STRATEGIC PLAN FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE CROSS-BORDER REGION KRŠ “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Regional Rural Development Standing Working Group in South Eastern Europe (SEE) and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.” This document is output of the IPA II Multi-country action programme 2014 Project ”Fostering regional cooperation and balanced territorial development of Western Balkan countries in the process towards EU integration – Support to the Regional Rural Development Standing Working Group (SWG) in South-East Europe” 2 BASELINE STUDY AND STRATEGIC PLAN FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE CROSS-BORDER REGION KRŠ Published by: Regional Rural Development Standing Working Group in SEE (SWG) Blvd. Goce Delcev 18, MRTV Building, 12th floor, 1000 Skopje, Macedonia Preparation for implementation of the Area Based Development (ABD) Approach in the Western Balkans Baseline Study and Strategic Plan for development of the cross-border region “Krš” On behalf of SWG: Boban Ilić Authors: Suzana Djordjević Milošević, Ivica Sivrić, Irena Djimrevska, in cooperation with stakeholders from the region “Krš” Editor: Damjan Surlevski Proofreading: Ana Vasileva Design: Filip Filipović Photos: SWG Head Office/Secretariat and Ivica Sivrić CIP - Каталогизација во публикација Национална и универзитетска библиотека "Св. Климент Охридски", Скопје 352(497) DJORDJEVIĆ Milošević, Suzana Preparation for implementation of the area based development (ABD) approach in the Western Balkans : Baseline study and strategic plan for development of the cross-border region "KRŠ" / [authors Suzana Djordjević Milošević, Ivica Sivrić, Irena Djimrevska]. -

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-Speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000

Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 A project of the German-Canadian Association of Alberta © 2010 Compiler: Manfred Prokop Annotated Bibliography of the Cultural History of the German-speaking Community in Alberta: 1882-2000. Fifth Up-Date: 2008-2009 In collaboration with the German-Canadian Association of Alberta German-Canadian Cultural Center, 8310 Roper Road, Edmonton, AB, Canada T6E 6E3 Compiler: Manfred Prokop 209 Tucker Boulevard, Okotoks, AB, Canada T1S 2K1 Phone/Fax: (403) 995-0321. E-Mail: [email protected] ISBN 0-9687876-0-6 © Manfred Prokop 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Overview ............................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Quickstart ................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Description of the Database ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Brief history of the project .................................................................................................................................... 2 Materials ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Sources ................................................................................................................................................................... -

RE-LAW LLP 4949 Bathurst Street, Suite 206 Toronto, Ontario M2R 1Y1 T

Aaron Rosenberg Email: [email protected] Direct Line: 416.789.4984 Fax: 416.429.2016 www.relawllp.ca Delivered by: E-mail File No.: 378.00018 July 28, 2020 Tyler Dawson, President Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association [email protected] Katherine Kay Stikeman Elliott LLP 5300 Commerce Court West 199 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario M5L 1B9 [email protected] Dear Ms. Kay and Mr. Dawson: Re: Anti-Competitive Conduct by Postmedia Network Inc. (“Postmedia”) and the Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association (“ALPGA”) I am writing on behalf of our clients, Sheila Gunn Reid, Keean Bexte, and Rebel News Network Ltd. (“Rebel News”). Please direct all future correspondence to the undersigned. We understand that our clients applied for membership with the ALPGA, and on July 27, 2020, as newly-elected president of the ALPGA, Mr. Dawson communicated its denial to Rebel News as follows (the “Denial”): Good morning, I have been elected as president of the Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association as of our annual general meeting this morning. I'm writing to inform you that the gallery has voted to reject the applications of Sheila Gunn Reid and Keean Bexte of the Rebel News Network Ltd. for membership to the Alberta Legislature Press Gallery Association. Take care, Tyler Dawson — Tyler Dawson RE-LAW LLP 4949 Bathurst Street, Suite 206 Toronto, Ontario M2R 1Y1 T. 416.840.7316 Fax. 416.429.2016 2 Alberta correspondent National Post [email protected] The Denial was communicated without reasons — the only stated reason for this decision is that the ALPGA “voted to reject the applications”. -

ALBERTA ENVIRONMENTAL APPEAL BOARD Decision

Appeal Nos. 01-106 and 108-D ALBERTA ENVIRONMENTAL APPEAL BOARD Decision Date of Decision – June 15, 2002 IN THE MATTER OF sections 91, 92, and 95 of the Environmental Protection and Enhancement Act, R.S.A. 2000, c. E-12; -and- IN THE MATTER OF appeals filed by Mr. Andy Dzurny and Mr. William Procyk with respect to Amending Approval No. 9767-01-09 issued on October 26, 2001, by the Director, Northeast Boreal Region, Regional Services, Alberta Environment, to Shell Chemicals Canada Ltd. Cite as: Dzurny et al. v. Director, Northeast Boreal Region, Regional Services, Alberta Environment re: Shell Chemicals Canada Ltd. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Board received Notices of Appeal from Mr. Andy Dzurny and Mr. William Procyk with respect to an amending approval issued by Alberta Environment to Shell Chemicals Canada Ltd. with respect to the operation of the Scotford Chemical Plant in Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta. According to standard practice, the Board wrote to the Alberta Energy and Utilities Board (AEUB) asking whether the matters included in these Notices of Appeal had been the subject of a review or hearing under the AEUB’s legislation. The AEUB advised the Board that it had held a hearing in relation to the Shell Scotford Chemical Plant. In response to this, the Board asked for submissions from Mr. Dzurny, Mr. Procyk, Shell Canada, and Alberta Environment as to whether the matters included in the Notices of Appeal had been the subject of a review or hearing under the AEUB’s legislation. Upon reviewing the documents provided by the AEUB and the submissions from the Parties to these appeals, the Board has concluded that the matters included in the Notices of Appeal were previously dealt with by the AEUB. -

Portail De L'éducation De Historica Canada the Great Teams

Portail de l'éducation de Historica Canada The Great Teams Overview This lesson plan is based on viewing the Footprint videos for the Edmonton Grads, Montreal Expos, Toronto Blue Jays and the World Series Championships, and the 1976 Canada Cup Team. The Edmonton Grads' astonishing record ended when they disbanded at the beginning of the Second World War. The conflict between East and West was as cold on the ice as off during the 1976 Canada Cup. The Toronto Blue Jay victory at the World Series helped to subdue ever-present concerns of American Manifest Destiny. Each of these teams has helped to represent Canada on the world stage, and in doing so, contributed to the constant evolution of Canadian identity. Aims To increase student awareness of the history of Canadian success in team sports; to increase student appreciation of the historical context of team competitions; to explore how Canadians have defined themselves and the nation through team sports; and, to critically investigate whether team competition is a forum for political and cultural understanding or a venue for increased cross-country animosity. Background When England lost to Germany in the 1990 soccer World Cup semifinal, historian Kenneth Clarke asked then-Prime Minister of Great Britain Margaret Thatcher, "Isn't it terrible about losing to the Germans at our national sport?" She replied, "I shouldn't worry too much; we've beaten them twice this century at theirs." This exchange speaks to the belief that sports is a less violent form of war, and that a country's history can be a story of successive conflicts with other nations.