On Remembrance and Forgetting in Julie Otsuka's Novels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Julie Otsuka's the Buddha in the Attic

Lost in the Passage 85 Feminist Studies in English Literature Vol.21, No. 3 (2013) Lost in the Passage: (Japanese American) Women in Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic JaeEun Yoo (Hanyang University) As is widely known, traditional psychoanalysis theorizes the mother-daughter relationship in negative terms; in order to grow into a mature individual, the daughter must sever emotional ties with her mother. As Marianne Hirsch writes, “a continual allegiance to the mother appears as regressive and potentially lethal; it must be transcended. Maturity can be reached only through an alignment with the paternal, by means of an angry and hostile break from the mother” (168). However, precisely because the mother-daughter relationship is conceptualized in this way—that is, as the site of intergenerational female alienation, many women writers have tried to re-imagine it as a source of strength and encouragement, though often not without conflict. Asian American feminist writers are no exception. Re- conceiving and restoring the mother-daughter relationship is even more complicated for Asian American writers as they face issues of race in addition to those of gender. Critics have long noticed the specific way these writers imagine Asian American daughters’ 86 JaeEun Yoo attempts to relate to and draw from their immigrant mothers—a relationship conventionally thought of as unbridgeable due to generation gap and culture differences. As Melinda Luisa De Jesus points out, “what U.S. third world feminist writers have added to this genre [Mother/daughter stories] is the delineation of how women of color of all generations must negotiate not only sexism in American society but its simultaneous intertwining with racism, classism, heterosexism, and imperialism” (4). -

Jap” to “Hero”: Resettlement, Enlistment, and the Construction of Japanese American Identity During WWII

From “Jap” to “Hero”: Resettlement, Enlistment, and the Construction of Japanese American Identity during WWII Maggie Harkins 3 Table of Contents I. Japanese Invasion: “The Problem of the Hour” II. “JAPS BOMB HAWAII!” Racism and Reactions to the Japanese American Community III. Enduring Relocation: “shikata ga nai” IV. Changing Family Roles within the Internment Camps V. “Striving to Create Goodwill” Student Resettlement VI. Nisei WACS: “A Testimony to Japanese American Loyalty” VII. “Go For Broke!” Fighting For Dignity and Freedom VIII. Heroism and Terrorism: Re-Assimilation into Anglo-American Society 4 On December 7, 1941 Japan staged a massive attack of the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawai’i. Mainland Americans huddled around their radios listening to the events unfold, while Hawaiians watched the Japanese Imperial Air Force drop bombs over their home. The United States was at war. Young men nationwide, including Lawson Sakai, a Japanese American college student in California, rushed to join the Armed Forces. On December 8, 1941 Lawson and three friends traveled to the nearest recruiting station to commit themselves to the United States Navy. Though his friends were accepted immediately, Sakai was delayed and eventually denied. “They told me I was an enemy alien!,” he remembered years later. 1 The recruiting officer’s reaction to Sakai’s attempted enlistment foreshadowed the intense racial discrimination that he and thousands of other Japanese Americans would face in the coming months. The Nisei, second-generation Japanese American citizens, viewed themselves as distinctly American. They had no connection to the imperial enemies who bombed their homeland and were determined to support the United States. -

Julie Otsuka on Her Family's Wartime Internment in Topaz

HANDOUT ONE Excerpt from “Julie Otsuka on Her Family’s Wartime Internment in Topaz, Utah” Dorothea Lange/National Archives and Records Administration By Julie Otsuka the middle of the racetrack, where she and the children would be sleeping that evening. My uncle, There is a photograph in the National Archives who is 8, is carrying his mother’s purse for her of my mother, uncle, and grandmother taken by beneath his left arm. Hanging from a canvas strap Dorothea Lange on April 29, 1942. The caption around his neck is a canteen, which is no doubt reads: “San Bruno, California. Family of Japanese filled with water. Why? Because he is going to ancestry arrives at assembly center at Tanforan “camp.” Race Track.” My mother, 10, is turned away from the camera and all you can see is a sliver of Clearly, my uncle had a different kind of camp her cheek, one ear, and two black braids pinned in mind—the kind of camp where you pitch to the top of her head. In the background is a tents and take hikes and get thirsty—and clearly, large concrete structure with a balcony—the his mother has allowed him to think this. But grandstands. My grandmother, 42, is wearing a he is only just now realizing his mistake, and the nice wool coat and listening intently to the man expression on his face is anxious and concerned. beside her, who is pointing out something in the Tanforan was a temporary detention center for distance—most likely the newly built barracks in thousands of Bay Area “evacuees” on their way THE BIG READsNATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka 1 Table of Contents When the Emperor Was Divine “Mostly though, they waited. For the mail. About the Book.................................................... 3 About the Author ................................................. 5 For the news. For Historical and Literary Context .............................. 8 the bells. For Other Works/Adaptations ................................... 10 breakfast and lunch Discussion Questions.......................................... 11 Additional Resources .......................................... 12 and dinner. For one Credits .............................................................. 13 day to be over and the next day to Preface begin.” Indicates interviews with the author and experts on this book. Internet access is required for this content. Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine follows one Japanese family uprooted from its Berkeley home after the start of World War II. After being delivered to a racetrack in Utah, they are forcibly relocated to an internment camp. They spend two harrowing years there before returning to a What is the NEA Big Read? home far less welcoming than it was before the war. Using A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big five distinct but intertwined perspectives, Otsuka's graceful Read broadens our understanding of our world, our prose evokes the family's range of responses to internment. communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a Culminating in a final brief and bitter chapter, Otsuka's novel good book. Managed by Arts Midwest, this initiative offers serves as a requiem for moral and civic decency in times of grants to support innovative community reading programs strife and fragmentation. designed around a single book. A great book combines enrichment with enchantment. It awakens our imagination and enlarges our humanity. -

TRANSFORMATION of the SELF: a Study of Submissiveness, Trauma, Guilt and Shame in Julie Otsuka’S When the Emperor Was Divine (2002)

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER TRANSFORMATION OF THE SELF: A Study of Submissiveness, Trauma, Guilt and Shame in Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine (2002) Ingegerd Stenport Essay/Degree Project: Advanced Research Essay, Literary Specialisation, 15 credits Program or/and course: EN2D04 Level: Second cycle Term/year: Vt/2016 Supervisor: Ronald Paul Examiner: Marius Hentea Report nr: Abstract Title: Transformation of the Self: a Study of Submissiveness, Trauma, Guilt and Shame in Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine (2002) Author: Ingegerd Stenport Supervisor: Ronald Paul Abstract: The internment of Japanese-American civilians during the Second World War caused many of the interned traumatic experiences. This essay is a contribution to the discussion of trauma theory in literature. By applying multiple theories of oppression, racism, discrimination and intergenerational transmitted trauma to Otsuka’s novel, the essay shows that the reimagined fictionalized trauma of past generations is illustrated in a psychologically realistic way. The focus of the argument is that the characters in When the Emperor Was Divine (2002) have been transformed and that the damage done during the internment lasts and that the healing process will not result in integrated selves. Memories of guilt and shame are shaped by a geographically and socially constructed oppression and discrimination and the appropriated stereotypes of the “alien enemy” become embedded in their transformed identities. Keywords: Julie Otsuka, When the Emperor Was Divine, Japanese American literature, Sansei generation, trauma, World War II internment, racism, oppression, discrimination Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Thesis 3 3. Trauma Theory and Previous Research 5 4. -

Download the Entire Journey Home Curriculum

Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in WWII Arkansas Journey Home Curriculum An interdisciplinary unit for 4th-6th grade students View of the Jerome Relocation Center as seen from the nearby train tracks, June 18, 1944. Courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration, ARC ID 539643, Photographer Charles Mace Kristin Dutcher Mann, Compiler and Editor Ryan Parson, Editor Vicki Gonterman Patricia Luzzi Susan Turner Purvis © 2004, Board of Trustees, University of Arkansas 2 ♦ Life Interrupted: Journey Home Life Interrupted: The Japanese American Experience in World War II Arkansas Life Interrupted is a partnership between the University of Arkansas at Little Rock Public History program and the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, Cali- fornia. Our mission is to research the experiences of Japanese Americans in World War II Arkansas and educate the citizens of Arkansas and the nation about the two camps at Jerome and Rohwer. Major funding for Life Interrupted was provided by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. We share the story of Japanese Americans because we honor our nation’s diversity. We believe in the importance of remembering our history to better guard against the prejudice that threatens liberty and equality in a democratic society. We strive as a metropolitan univer- sity and a world-class museum and to provide a voice for Japanese Americans and a forum that enables all people to explore their own heritage and culture. We promote continual exploration of the meaning and value of ethnicity in our country through programs that preserve individual dignity, strengthen our communities, and increase respect among all people. -

Additional Online and Print Resources

ONLINE RESOURCES HISTORY Japanese Picture Brides in Central Valley An 8-minute video featuring photos from the era, translated interviews with actual picture brides, and a brief historical overview of their lives, social structures, and the situation for their children. http://video.answers.com/japanese-picture-bride-phenomena-in-central-valley-300995146 Japanese Picture Brides: Building a Family Through Photographs A thoughtful article discussing the traditions, hopes, and pitfalls around Japanese marriages arranged through photographs. Includes several photos of bachelors, newlyweds, newly-arrived picture brides, and families. http://www.kcet.org/socal/departures/little-tokyo/japanese-picture-brides-building-a-family-through- photographs.html Voices of Japanese-American Internees A 3-part lesson plan produced by the Anti-Defamation league. Includes a link to the short film “We Are Americans.” http://www.adl.org/education/curriculum_connections/summer_2008/default.asp Densho – The Japanese American Legacy Project A comprehensive independent archive, including extensive video interviews, downloadable curriculum, and other documents. http://www.densho.org/densho.asp JARDA – Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives A comprehensive archive from the University of California, with primary resources and a variety of lesson plans. Photos, audio recordings, timelines, and more. http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/ JARDA – Links and resources The University of California’s own collection of resource links. http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/related-resources.html#curricula -

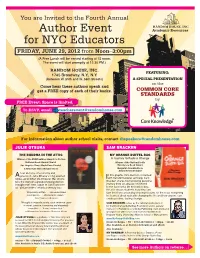

Author Event for NYC Educators

You are Invited to the Fourth Annual Author Event Academic Resources for NYC Educators FRIDAY, JUNE 29, 2012 from Noon–3:00pm (A Free Lunch will be served starting at 12 noon. The event will start promptly at 12:30 PM.) RANDOM HOUSE, INC. FEATURING: 1745 Broadway, N.Y., N.Y. (between W. 55th and W. 56th Streets) A SPECIAL PRESENTATION on the Come hear these authors speak and get a FREE copy of each of their books. COMMON CORE STANDARDS by FREE Event. Space is limited. To RSVP, email [email protected] For information about author school visits, contact [email protected] JULIE OTSUKA SAM BRACKEN THE BUDDHA IN THE AttIC MY ORANGE DUFFEL BAG Winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction A Journey to Radical Change National Book Award Finalist Winner of the National Indie Los Angeles Times Book Prize Finalist Excellence Book Award A New York Times Notable Book Benjamin Franklin Book Award Silver Medalist tour de force of economy and A precision, Julie Otsuka’s long awaited n this graphic mini-memoir combined follow-up to When the Emperor Was Divine Iwith transformational self-help, Sam tells the story of a group of young women Bracken shares his harrowing personal brought over from Japan to San Francisco journey from an abusive childhood as “picture brides” nearly a century ago. to the successful life he leads today. He also shows students how they can “Exquisitely written. An understated turn their lives around by sharing his rules for the road: everything masterpiece. Destined to endure.” he learned about radically changing his life and how anyone can —SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE create positive, lasting change. -

Lesson Plans and Resources for the Buddha in the Attic Table of Contents

Lesson Plans and Resources for The Buddha in the Attic Table of Contents 1. Overview and Essential Questions 2. In-Class Introduction + Supplements – Literary and Historical focus - Photographs of Japanese Picture Brides arriving in California - Map of Japan - Photograph of Otsuka family in an internment camp - Timeline of Japanese immigration 3. Common Core Standards Alignment 4. Reader Response Questions 5. Literary Log Prompts + Worksheets - Japanese Culture - Asking Questions 6. Suggested Analytical Assessments 7. Suggested Creative Assessments 8. Online Resources 9. Print Resources - Review by Elizabeth Day for The Guardian - Review by Ron Charles for The Washington Post - Interview by Jane Ciabattari for The Daily Beast - “A Sikh Temple’s Century” by Bhira Backhaus 10. One Book, One Philadelphia Supporters These resources are all available, both separately and together, at www.freelibrary.org/onebook Please send any comments or feedback about these resources to [email protected]. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS The materials in this unit plan are meant to be flexible and easy to adapt to your own classroom. Each chapter has discussion questions provided in a later section. However, for students reading the entire book, there are several themes that connect the stories. Through reading the book and completing any of the suggested activities, students can achieve any number of the following understandings: To understand a culture, you must see the daily life of many – not just the experiences of a few. Despite being a nation of immigration, America has a long tradition of keeping newcomers on the outside. Fiction can bring history to life. Students should be introduced to the following key questions as they begin reading, and keep them in mind as they work through the book. -

J Hen the Emperor Was Divine

Acknowledgements: 2008 JULIE OTSUKA Erica Harth Susumu Ito Ipswich Reads...One Book! Martha Mauser Harvey Schwartz May Takayanagi j hen the Emperor Carl Takei Josh Wilber was Divine We are especially grateful for the assistance and advice of Margie Yamamoto, Co-President, New England Chapter, Japanese-American Citizens League. The Ipswich Reads...One Book! is funded by the Board of Trustees of the Ipswich Public Library . Credits: Ansel Adams's Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar Brochure Cover: Joyce Yuki Nakamura, bust portrait, facing front Backround Photo/2nd page: Farm, farm workers, Mt. Williamson in background Source: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/anseladams/aamsp.html Julie Otsuka was born and raised in California. She is Julie Otsuka Photo © Daryl N Long a graduate of Yale University and received her M.F.A. Source: http://my.champlain.edu/public/community.book.program from Columbia. She lives in New York City. Otsuka is one of the winners of the Sixth Annual Asian Ameri- Author’s Biography & Quote Source: http://www.asiasource.org/arts/julieotsuka.cfm can Literary Awards and was honored at the Asia Society on December 8, 2003. Praises For the Book Source: http://www.randomhouse.com/anchor/catalog/display.pperl? isbn=9780385721813 Otsuka, Julie. When the Emperor Was Divine. NY: Anchor Books, 2002. Cover design by John Gall "I wanted to write a novel about real people... their experience is universal not only for Japanese Ameri- IPSWICH PUBLIC LIBRARY cans, but for people of any ethnic group. All through- 25 North Main Street This is the fourth year of our town-wide out history people have been rounded up and sent Ipswich, MA 01938 reading program. -

Yoshiko Uchida Papers 1903-1994

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf0c600134 Online items available Finding Aid to the Yoshiko Uchida papers 1903-1994 Bancroft Library Staff The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Yoshiko Uchida BANC MSS 86/97 c 1 papers 1903-1994 Finding Aid to the Yoshiko Uchida papers 1903-1994 Collection number: BANC MSS 86/97 c The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] Finding Aid Author(s): Bancroft Library Staff Finding Aid Encoded By: GenX Copyright 1998 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Yoshiko Uchida papers Date (inclusive): 1903-1994 Date (bulk): 1942-1992 Collection Number: BANC MSS 86/97 c Compiler: Uchida, Yoshiko Physical Description: linear feet: 32Number of containers: 67 boxes, 1 carton, 2 volumes, 2 oversize folders, 14 oversize boxes, 1 portfolio26 digital objects Repository: The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, CA 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] Abstract: Consists of Uchida's correspondence, writings, and professional files, along with a small amount of personal and family papers, providing insight into the life of a successful and distinguished author, as well as her experiences as a Japanese-American growing up in Berkeley, Calif., and internment camps during the war years. -

Lives and Legacy by Joyce Nao Takahashi

Japanese American Alumnae of the University of California, Berkeley: Lives and Legacy Joyce Nao Takahashi A Project of the Japanese American Women/Alumnae of the University of California, Berkeley Front photo: 1926 Commencement, University of California, Berkeley. Photo Courtesy of Joyce N. Takahashi Copyright © 2013 by Joyce Nao Takahashi All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. Preface and Acknowledgements I undertook the writing of the article, Japanese American Alumnae: Their Lives and Legacy in 2010 when the editors of the Chronicle of the University of California, Carroll Brentano, Ann Lage and Kathryn M. Neal were planning their Issue on Student Life. They contacted me because they wanted to include an article on Japanese American alumnae and they knew that the Japanese American Women/Alumnae of UC Berkeley (JAWAUCB), a California Alumni club, was conducting oral histories of many of our members, in an attempt to piece together our evolution from the Japanese Women’s Student Club (JWSC). As the daughter of one of the founders of the original JWSC, I agreed to research and to write the JWSC/JAWAUCB story. I completed the article in 2010, but the publication of the Chronicle of the University of California’s issue on Student Life has suffered unfortunate delays. Because I wanted to distribute our story while it was still timely, I am printing a limited number of copies of the article in a book form I would like to thank fellow JAWAUCB board members, who provided encouragement, especially during 2010, Mary (Nakata) Tomita, oral history chair, May (Omura) Hirose, historian, and Irene (Suzuki) Tekawa, chair.