Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine, a Heart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Julie Otsuka's the Buddha in the Attic

Lost in the Passage 85 Feminist Studies in English Literature Vol.21, No. 3 (2013) Lost in the Passage: (Japanese American) Women in Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic JaeEun Yoo (Hanyang University) As is widely known, traditional psychoanalysis theorizes the mother-daughter relationship in negative terms; in order to grow into a mature individual, the daughter must sever emotional ties with her mother. As Marianne Hirsch writes, “a continual allegiance to the mother appears as regressive and potentially lethal; it must be transcended. Maturity can be reached only through an alignment with the paternal, by means of an angry and hostile break from the mother” (168). However, precisely because the mother-daughter relationship is conceptualized in this way—that is, as the site of intergenerational female alienation, many women writers have tried to re-imagine it as a source of strength and encouragement, though often not without conflict. Asian American feminist writers are no exception. Re- conceiving and restoring the mother-daughter relationship is even more complicated for Asian American writers as they face issues of race in addition to those of gender. Critics have long noticed the specific way these writers imagine Asian American daughters’ 86 JaeEun Yoo attempts to relate to and draw from their immigrant mothers—a relationship conventionally thought of as unbridgeable due to generation gap and culture differences. As Melinda Luisa De Jesus points out, “what U.S. third world feminist writers have added to this genre [Mother/daughter stories] is the delineation of how women of color of all generations must negotiate not only sexism in American society but its simultaneous intertwining with racism, classism, heterosexism, and imperialism” (4). -

Julie Otsuka on Her Family's Wartime Internment in Topaz

HANDOUT ONE Excerpt from “Julie Otsuka on Her Family’s Wartime Internment in Topaz, Utah” Dorothea Lange/National Archives and Records Administration By Julie Otsuka the middle of the racetrack, where she and the children would be sleeping that evening. My uncle, There is a photograph in the National Archives who is 8, is carrying his mother’s purse for her of my mother, uncle, and grandmother taken by beneath his left arm. Hanging from a canvas strap Dorothea Lange on April 29, 1942. The caption around his neck is a canteen, which is no doubt reads: “San Bruno, California. Family of Japanese filled with water. Why? Because he is going to ancestry arrives at assembly center at Tanforan “camp.” Race Track.” My mother, 10, is turned away from the camera and all you can see is a sliver of Clearly, my uncle had a different kind of camp her cheek, one ear, and two black braids pinned in mind—the kind of camp where you pitch to the top of her head. In the background is a tents and take hikes and get thirsty—and clearly, large concrete structure with a balcony—the his mother has allowed him to think this. But grandstands. My grandmother, 42, is wearing a he is only just now realizing his mistake, and the nice wool coat and listening intently to the man expression on his face is anxious and concerned. beside her, who is pointing out something in the Tanforan was a temporary detention center for distance—most likely the newly built barracks in thousands of Bay Area “evacuees” on their way THE BIG READsNATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka 1 Table of Contents When the Emperor Was Divine “Mostly though, they waited. For the mail. About the Book.................................................... 3 About the Author ................................................. 5 For the news. For Historical and Literary Context .............................. 8 the bells. For Other Works/Adaptations ................................... 10 breakfast and lunch Discussion Questions.......................................... 11 Additional Resources .......................................... 12 and dinner. For one Credits .............................................................. 13 day to be over and the next day to Preface begin.” Indicates interviews with the author and experts on this book. Internet access is required for this content. Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine follows one Japanese family uprooted from its Berkeley home after the start of World War II. After being delivered to a racetrack in Utah, they are forcibly relocated to an internment camp. They spend two harrowing years there before returning to a What is the NEA Big Read? home far less welcoming than it was before the war. Using A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big five distinct but intertwined perspectives, Otsuka's graceful Read broadens our understanding of our world, our prose evokes the family's range of responses to internment. communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a Culminating in a final brief and bitter chapter, Otsuka's novel good book. Managed by Arts Midwest, this initiative offers serves as a requiem for moral and civic decency in times of grants to support innovative community reading programs strife and fragmentation. designed around a single book. A great book combines enrichment with enchantment. It awakens our imagination and enlarges our humanity. -

Additional Online and Print Resources

ONLINE RESOURCES HISTORY Japanese Picture Brides in Central Valley An 8-minute video featuring photos from the era, translated interviews with actual picture brides, and a brief historical overview of their lives, social structures, and the situation for their children. http://video.answers.com/japanese-picture-bride-phenomena-in-central-valley-300995146 Japanese Picture Brides: Building a Family Through Photographs A thoughtful article discussing the traditions, hopes, and pitfalls around Japanese marriages arranged through photographs. Includes several photos of bachelors, newlyweds, newly-arrived picture brides, and families. http://www.kcet.org/socal/departures/little-tokyo/japanese-picture-brides-building-a-family-through- photographs.html Voices of Japanese-American Internees A 3-part lesson plan produced by the Anti-Defamation league. Includes a link to the short film “We Are Americans.” http://www.adl.org/education/curriculum_connections/summer_2008/default.asp Densho – The Japanese American Legacy Project A comprehensive independent archive, including extensive video interviews, downloadable curriculum, and other documents. http://www.densho.org/densho.asp JARDA – Japanese American Relocation Digital Archives A comprehensive archive from the University of California, with primary resources and a variety of lesson plans. Photos, audio recordings, timelines, and more. http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/ JARDA – Links and resources The University of California’s own collection of resource links. http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/jarda/related-resources.html#curricula -

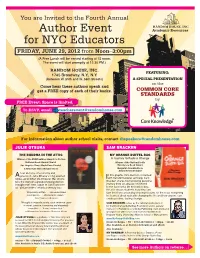

Author Event for NYC Educators

You are Invited to the Fourth Annual Author Event Academic Resources for NYC Educators FRIDAY, JUNE 29, 2012 from Noon–3:00pm (A Free Lunch will be served starting at 12 noon. The event will start promptly at 12:30 PM.) RANDOM HOUSE, INC. FEATURING: 1745 Broadway, N.Y., N.Y. (between W. 55th and W. 56th Streets) A SPECIAL PRESENTATION on the Come hear these authors speak and get a FREE copy of each of their books. COMMON CORE STANDARDS by FREE Event. Space is limited. To RSVP, email [email protected] For information about author school visits, contact [email protected] JULIE OTSUKA SAM BRACKEN THE BUDDHA IN THE AttIC MY ORANGE DUFFEL BAG Winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction A Journey to Radical Change National Book Award Finalist Winner of the National Indie Los Angeles Times Book Prize Finalist Excellence Book Award A New York Times Notable Book Benjamin Franklin Book Award Silver Medalist tour de force of economy and A precision, Julie Otsuka’s long awaited n this graphic mini-memoir combined follow-up to When the Emperor Was Divine Iwith transformational self-help, Sam tells the story of a group of young women Bracken shares his harrowing personal brought over from Japan to San Francisco journey from an abusive childhood as “picture brides” nearly a century ago. to the successful life he leads today. He also shows students how they can “Exquisitely written. An understated turn their lives around by sharing his rules for the road: everything masterpiece. Destined to endure.” he learned about radically changing his life and how anyone can —SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE create positive, lasting change. -

Lesson Plans and Resources for the Buddha in the Attic Table of Contents

Lesson Plans and Resources for The Buddha in the Attic Table of Contents 1. Overview and Essential Questions 2. In-Class Introduction + Supplements – Literary and Historical focus - Photographs of Japanese Picture Brides arriving in California - Map of Japan - Photograph of Otsuka family in an internment camp - Timeline of Japanese immigration 3. Common Core Standards Alignment 4. Reader Response Questions 5. Literary Log Prompts + Worksheets - Japanese Culture - Asking Questions 6. Suggested Analytical Assessments 7. Suggested Creative Assessments 8. Online Resources 9. Print Resources - Review by Elizabeth Day for The Guardian - Review by Ron Charles for The Washington Post - Interview by Jane Ciabattari for The Daily Beast - “A Sikh Temple’s Century” by Bhira Backhaus 10. One Book, One Philadelphia Supporters These resources are all available, both separately and together, at www.freelibrary.org/onebook Please send any comments or feedback about these resources to [email protected]. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS The materials in this unit plan are meant to be flexible and easy to adapt to your own classroom. Each chapter has discussion questions provided in a later section. However, for students reading the entire book, there are several themes that connect the stories. Through reading the book and completing any of the suggested activities, students can achieve any number of the following understandings: To understand a culture, you must see the daily life of many – not just the experiences of a few. Despite being a nation of immigration, America has a long tradition of keeping newcomers on the outside. Fiction can bring history to life. Students should be introduced to the following key questions as they begin reading, and keep them in mind as they work through the book. -

J Hen the Emperor Was Divine

Acknowledgements: 2008 JULIE OTSUKA Erica Harth Susumu Ito Ipswich Reads...One Book! Martha Mauser Harvey Schwartz May Takayanagi j hen the Emperor Carl Takei Josh Wilber was Divine We are especially grateful for the assistance and advice of Margie Yamamoto, Co-President, New England Chapter, Japanese-American Citizens League. The Ipswich Reads...One Book! is funded by the Board of Trustees of the Ipswich Public Library . Credits: Ansel Adams's Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar Brochure Cover: Joyce Yuki Nakamura, bust portrait, facing front Backround Photo/2nd page: Farm, farm workers, Mt. Williamson in background Source: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/anseladams/aamsp.html Julie Otsuka was born and raised in California. She is Julie Otsuka Photo © Daryl N Long a graduate of Yale University and received her M.F.A. Source: http://my.champlain.edu/public/community.book.program from Columbia. She lives in New York City. Otsuka is one of the winners of the Sixth Annual Asian Ameri- Author’s Biography & Quote Source: http://www.asiasource.org/arts/julieotsuka.cfm can Literary Awards and was honored at the Asia Society on December 8, 2003. Praises For the Book Source: http://www.randomhouse.com/anchor/catalog/display.pperl? isbn=9780385721813 Otsuka, Julie. When the Emperor Was Divine. NY: Anchor Books, 2002. Cover design by John Gall "I wanted to write a novel about real people... their experience is universal not only for Japanese Ameri- IPSWICH PUBLIC LIBRARY cans, but for people of any ethnic group. All through- 25 North Main Street This is the fourth year of our town-wide out history people have been rounded up and sent Ipswich, MA 01938 reading program. -

Migrating Fictions

MIGRATING FICTIONS Migrating Fictions Gender, Race, and Citizenship in U.S. Internal Displacements ABIGAIL G. H. MANZELLA THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2018 by Abigail G. H. Manzella. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Manzella, Abigail G. H., author. Title: Migrating fictions : gender, race, and citizenship in U.S. internal displacements / Abigail G. H. Manzella. Description: Columbus : The Ohio State University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017036404 | ISBN 9780814213582 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 0814213588 (cloth ; alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: American fiction—20th century—History and criticism. | Migration, Internal, in literature. | Race relations in literature. | Displacement (Psychology) in literature. | Refugees in literature. Classification: LCC PS379 .M295 2018 | DDC 813/.509355—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036404 Cover design by Andrew Brozyna Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Front cover images: (1) Jack Delano, “Group of Florida migrants on their way to Cranberry, New Jersey, to pick potatoes,” Near Shawboro, North Carolina. Library of Congress, July 1940. (2) Clem Albers, “Persons of Japanese ancestry arrive at the Santa Anita Assembly center from Santa Anita Assembly center from San Pedro, California. Evacuees lived at this center at the Santa Anita race track before being moved inland to relocation centers,” Arcadia, California. National Archives, April 5, 1942. Back cover image: Dorothea Lange, “Cheap auto camp housing for citrus workers,” Tulare County, California. National Archives, February 1940. Published by The Ohio State University Press The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka About the author Julie Otsuka was born in Palo Alto and studied art at Yale University. After pursuing a career as a painter, she turned to fiction at age 30. One of her short stories was included in Scribner's Best of the Fiction Workshops 1998, edited by Carol Shields. When the Emperor Was Divine is her first novel. About the book Julia Otsuka's quietly disturbing novel opens with a woman reading a sign in a post office window. It is Berkeley, California, the spring of 1942. Pearl Harbor has been attacked, the war is on, and though the precise message on the sign is not revealed, its impact on the woman who reads it is immediate and profound. It is, in many ways she cannot yet foresee, a sign of things to come. She readies herself and her two young children for a journey that will take them to the high desert plains of Utah and into a world that will shatter their illusions forever. They travel by train and gradually the reader discovers that all on board are Japanese American, that the shades must be pulled down at night so as not to invite rock-throwing, and that their destination is an internment camp where they will be imprisoned "for their own safety" until the war is over. With stark clarity and an unflinching gaze, Otsuka explores the inner lives of her main characters—the mother, daughter, and son—as they struggle to understand their fate and long for the father whom they have not seen since he was whisked away, in slippers and handcuffs, on the evening of Pearl Harbor. -

NEA Big Read 2018.Indd

PASADENA PUBLIC LIBRARY PRESENTS “NEA Big Read is a program of the National Endowment for the Arts in partnership with Arts Midwest.” When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka Pasadena Public Library presents the National Endowment for the Arts’ NEA Big Read, which broadens our understanding of our world, our communities and ourselves through the joy of sharing a good book. This month the library will feature programming designed around the book When the Emperor Was Divine, by author Julie Otsuka. Please join us in the Big Read! FEBRUARY 2018 About the Book About the Author When the Emperor was Divine is a historical fi ction novel written by Julie Otsuka is an award-winning Japanese American author known for her historical fi ction American author Julie Otsuka about a Japanese American family sent novels calling attention to the plight of Japanese Americans throughout World War II. to an internment camp in the Utah desert during World War II. Loosely She did not live through the Japanese internment period, but her parents did, which gives based on the wartime experiences of Otsuka’s mother’s family, the Otsuka a unique and personal perspective on the matter. Born and raised in California, she novel is written through the perspective of four Japanese American studied art at Yale University. She pursued a career as a painter for several years before family members, a father, a mother, a son, and a daughter. The family turning to fi ction writing at age 30. Otsuka’s artistic attention to detail and great descriptions members remain nameless, giving their story a universal quality. -

Social Identity of Japanese Americans in Julie Otsuka's

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Bc. Lucie Lemonová Social Identity of Japanese Americans in Julie Otsuka’s Historical Novels Sociální identita japonských Američanů v historických románech Julie Ocuky Diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Prof. PhDr. Josef Jařab, CSc. Olomouc 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem diplomovou práci na téma „Social Identity of Japanese Americans in Julie Otsuka’s Historical Novels“ vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V Olomouci dne................... Podpis ............................ Acknowledgment I would like to thank my supervisor Prof. PhDr. Josef Jařab, CSc. for his guidance and valuable comments which helped me during the whole process of writing this diploma thesis. Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 6 1 The Concepts of Social Identity ........................................................................................ 8 1. 1 Social Identity .............................................................................................................. 8 1. 2 The Concept of Ethnic Identity .................................................................................... 9 1. 3 The Concept of National Identity ............................................................................... 11 1. 4 Ethnic Identity in Relation to Assimilation ............................................................... -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Breaking the Silence: An analysis of family memory and identity construction in Japanese-American internment novels“ verfasst von / submitted by Sophie Asamer BA BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2018 / Vienna 2018 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066844 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Anglophone Literatures and degree programme as it appears on Cultures UG2002 the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alexandra Ganser-Blumenau Acknowledgments: The finalization of this thesis marks an important step for me, not only academically, but also as a personal achievement. While getting to this point was not always easy, I am immensely grateful for the opportunity to broaden my knowledge on so many levels. I would like to thank my supervisor, Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Alexandra Ganser-Blumenau for her help with gathering my thoughts and great suggestions for further reading. I would also like to thank my family, who was so incredibly patient with me over the last years, my boyfriend for his endless support and encouragements, and Jenny Atkinson, who is a great friend and played an essential part in helping me finalize this project. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................