Additional Online and Print Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women in Julie Otsuka's the Buddha in the Attic

Lost in the Passage 85 Feminist Studies in English Literature Vol.21, No. 3 (2013) Lost in the Passage: (Japanese American) Women in Julie Otsuka’s The Buddha in the Attic JaeEun Yoo (Hanyang University) As is widely known, traditional psychoanalysis theorizes the mother-daughter relationship in negative terms; in order to grow into a mature individual, the daughter must sever emotional ties with her mother. As Marianne Hirsch writes, “a continual allegiance to the mother appears as regressive and potentially lethal; it must be transcended. Maturity can be reached only through an alignment with the paternal, by means of an angry and hostile break from the mother” (168). However, precisely because the mother-daughter relationship is conceptualized in this way—that is, as the site of intergenerational female alienation, many women writers have tried to re-imagine it as a source of strength and encouragement, though often not without conflict. Asian American feminist writers are no exception. Re- conceiving and restoring the mother-daughter relationship is even more complicated for Asian American writers as they face issues of race in addition to those of gender. Critics have long noticed the specific way these writers imagine Asian American daughters’ 86 JaeEun Yoo attempts to relate to and draw from their immigrant mothers—a relationship conventionally thought of as unbridgeable due to generation gap and culture differences. As Melinda Luisa De Jesus points out, “what U.S. third world feminist writers have added to this genre [Mother/daughter stories] is the delineation of how women of color of all generations must negotiate not only sexism in American society but its simultaneous intertwining with racism, classism, heterosexism, and imperialism” (4). -

Jap” to “Hero”: Resettlement, Enlistment, and the Construction of Japanese American Identity During WWII

From “Jap” to “Hero”: Resettlement, Enlistment, and the Construction of Japanese American Identity during WWII Maggie Harkins 3 Table of Contents I. Japanese Invasion: “The Problem of the Hour” II. “JAPS BOMB HAWAII!” Racism and Reactions to the Japanese American Community III. Enduring Relocation: “shikata ga nai” IV. Changing Family Roles within the Internment Camps V. “Striving to Create Goodwill” Student Resettlement VI. Nisei WACS: “A Testimony to Japanese American Loyalty” VII. “Go For Broke!” Fighting For Dignity and Freedom VIII. Heroism and Terrorism: Re-Assimilation into Anglo-American Society 4 On December 7, 1941 Japan staged a massive attack of the Pearl Harbor naval base in Hawai’i. Mainland Americans huddled around their radios listening to the events unfold, while Hawaiians watched the Japanese Imperial Air Force drop bombs over their home. The United States was at war. Young men nationwide, including Lawson Sakai, a Japanese American college student in California, rushed to join the Armed Forces. On December 8, 1941 Lawson and three friends traveled to the nearest recruiting station to commit themselves to the United States Navy. Though his friends were accepted immediately, Sakai was delayed and eventually denied. “They told me I was an enemy alien!,” he remembered years later. 1 The recruiting officer’s reaction to Sakai’s attempted enlistment foreshadowed the intense racial discrimination that he and thousands of other Japanese Americans would face in the coming months. The Nisei, second-generation Japanese American citizens, viewed themselves as distinctly American. They had no connection to the imperial enemies who bombed their homeland and were determined to support the United States. -

Julie Otsuka on Her Family's Wartime Internment in Topaz

HANDOUT ONE Excerpt from “Julie Otsuka on Her Family’s Wartime Internment in Topaz, Utah” Dorothea Lange/National Archives and Records Administration By Julie Otsuka the middle of the racetrack, where she and the children would be sleeping that evening. My uncle, There is a photograph in the National Archives who is 8, is carrying his mother’s purse for her of my mother, uncle, and grandmother taken by beneath his left arm. Hanging from a canvas strap Dorothea Lange on April 29, 1942. The caption around his neck is a canteen, which is no doubt reads: “San Bruno, California. Family of Japanese filled with water. Why? Because he is going to ancestry arrives at assembly center at Tanforan “camp.” Race Track.” My mother, 10, is turned away from the camera and all you can see is a sliver of Clearly, my uncle had a different kind of camp her cheek, one ear, and two black braids pinned in mind—the kind of camp where you pitch to the top of her head. In the background is a tents and take hikes and get thirsty—and clearly, large concrete structure with a balcony—the his mother has allowed him to think this. But grandstands. My grandmother, 42, is wearing a he is only just now realizing his mistake, and the nice wool coat and listening intently to the man expression on his face is anxious and concerned. beside her, who is pointing out something in the Tanforan was a temporary detention center for distance—most likely the newly built barracks in thousands of Bay Area “evacuees” on their way THE BIG READsNATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka 1 Table of Contents When the Emperor Was Divine “Mostly though, they waited. For the mail. About the Book.................................................... 3 About the Author ................................................. 5 For the news. For Historical and Literary Context .............................. 8 the bells. For Other Works/Adaptations ................................... 10 breakfast and lunch Discussion Questions.......................................... 11 Additional Resources .......................................... 12 and dinner. For one Credits .............................................................. 13 day to be over and the next day to Preface begin.” Indicates interviews with the author and experts on this book. Internet access is required for this content. Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine follows one Japanese family uprooted from its Berkeley home after the start of World War II. After being delivered to a racetrack in Utah, they are forcibly relocated to an internment camp. They spend two harrowing years there before returning to a What is the NEA Big Read? home far less welcoming than it was before the war. Using A program of the National Endowment for the Arts, NEA Big five distinct but intertwined perspectives, Otsuka's graceful Read broadens our understanding of our world, our prose evokes the family's range of responses to internment. communities, and ourselves through the joy of sharing a Culminating in a final brief and bitter chapter, Otsuka's novel good book. Managed by Arts Midwest, this initiative offers serves as a requiem for moral and civic decency in times of grants to support innovative community reading programs strife and fragmentation. designed around a single book. A great book combines enrichment with enchantment. It awakens our imagination and enlarges our humanity. -

TRANSFORMATION of the SELF: a Study of Submissiveness, Trauma, Guilt and Shame in Julie Otsuka’S When the Emperor Was Divine (2002)

INSTITUTIONEN FÖR SPRÅK OCH LITTERATURER TRANSFORMATION OF THE SELF: A Study of Submissiveness, Trauma, Guilt and Shame in Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine (2002) Ingegerd Stenport Essay/Degree Project: Advanced Research Essay, Literary Specialisation, 15 credits Program or/and course: EN2D04 Level: Second cycle Term/year: Vt/2016 Supervisor: Ronald Paul Examiner: Marius Hentea Report nr: Abstract Title: Transformation of the Self: a Study of Submissiveness, Trauma, Guilt and Shame in Julie Otsuka’s When the Emperor Was Divine (2002) Author: Ingegerd Stenport Supervisor: Ronald Paul Abstract: The internment of Japanese-American civilians during the Second World War caused many of the interned traumatic experiences. This essay is a contribution to the discussion of trauma theory in literature. By applying multiple theories of oppression, racism, discrimination and intergenerational transmitted trauma to Otsuka’s novel, the essay shows that the reimagined fictionalized trauma of past generations is illustrated in a psychologically realistic way. The focus of the argument is that the characters in When the Emperor Was Divine (2002) have been transformed and that the damage done during the internment lasts and that the healing process will not result in integrated selves. Memories of guilt and shame are shaped by a geographically and socially constructed oppression and discrimination and the appropriated stereotypes of the “alien enemy” become embedded in their transformed identities. Keywords: Julie Otsuka, When the Emperor Was Divine, Japanese American literature, Sansei generation, trauma, World War II internment, racism, oppression, discrimination Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Thesis 3 3. Trauma Theory and Previous Research 5 4. -

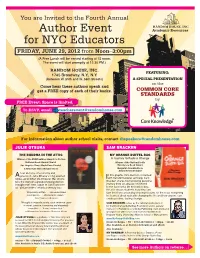

Author Event for NYC Educators

You are Invited to the Fourth Annual Author Event Academic Resources for NYC Educators FRIDAY, JUNE 29, 2012 from Noon–3:00pm (A Free Lunch will be served starting at 12 noon. The event will start promptly at 12:30 PM.) RANDOM HOUSE, INC. FEATURING: 1745 Broadway, N.Y., N.Y. (between W. 55th and W. 56th Streets) A SPECIAL PRESENTATION on the Come hear these authors speak and get a FREE copy of each of their books. COMMON CORE STANDARDS by FREE Event. Space is limited. To RSVP, email [email protected] For information about author school visits, contact [email protected] JULIE OTSUKA SAM BRACKEN THE BUDDHA IN THE AttIC MY ORANGE DUFFEL BAG Winner of the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction A Journey to Radical Change National Book Award Finalist Winner of the National Indie Los Angeles Times Book Prize Finalist Excellence Book Award A New York Times Notable Book Benjamin Franklin Book Award Silver Medalist tour de force of economy and A precision, Julie Otsuka’s long awaited n this graphic mini-memoir combined follow-up to When the Emperor Was Divine Iwith transformational self-help, Sam tells the story of a group of young women Bracken shares his harrowing personal brought over from Japan to San Francisco journey from an abusive childhood as “picture brides” nearly a century ago. to the successful life he leads today. He also shows students how they can “Exquisitely written. An understated turn their lives around by sharing his rules for the road: everything masterpiece. Destined to endure.” he learned about radically changing his life and how anyone can —SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE create positive, lasting change. -

Lesson Plans and Resources for the Buddha in the Attic Table of Contents

Lesson Plans and Resources for The Buddha in the Attic Table of Contents 1. Overview and Essential Questions 2. In-Class Introduction + Supplements – Literary and Historical focus - Photographs of Japanese Picture Brides arriving in California - Map of Japan - Photograph of Otsuka family in an internment camp - Timeline of Japanese immigration 3. Common Core Standards Alignment 4. Reader Response Questions 5. Literary Log Prompts + Worksheets - Japanese Culture - Asking Questions 6. Suggested Analytical Assessments 7. Suggested Creative Assessments 8. Online Resources 9. Print Resources - Review by Elizabeth Day for The Guardian - Review by Ron Charles for The Washington Post - Interview by Jane Ciabattari for The Daily Beast - “A Sikh Temple’s Century” by Bhira Backhaus 10. One Book, One Philadelphia Supporters These resources are all available, both separately and together, at www.freelibrary.org/onebook Please send any comments or feedback about these resources to [email protected]. ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS The materials in this unit plan are meant to be flexible and easy to adapt to your own classroom. Each chapter has discussion questions provided in a later section. However, for students reading the entire book, there are several themes that connect the stories. Through reading the book and completing any of the suggested activities, students can achieve any number of the following understandings: To understand a culture, you must see the daily life of many – not just the experiences of a few. Despite being a nation of immigration, America has a long tradition of keeping newcomers on the outside. Fiction can bring history to life. Students should be introduced to the following key questions as they begin reading, and keep them in mind as they work through the book. -

J Hen the Emperor Was Divine

Acknowledgements: 2008 JULIE OTSUKA Erica Harth Susumu Ito Ipswich Reads...One Book! Martha Mauser Harvey Schwartz May Takayanagi j hen the Emperor Carl Takei Josh Wilber was Divine We are especially grateful for the assistance and advice of Margie Yamamoto, Co-President, New England Chapter, Japanese-American Citizens League. The Ipswich Reads...One Book! is funded by the Board of Trustees of the Ipswich Public Library . Credits: Ansel Adams's Photographs of Japanese-American Internment at Manzanar Brochure Cover: Joyce Yuki Nakamura, bust portrait, facing front Backround Photo/2nd page: Farm, farm workers, Mt. Williamson in background Source: http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/anseladams/aamsp.html Julie Otsuka was born and raised in California. She is Julie Otsuka Photo © Daryl N Long a graduate of Yale University and received her M.F.A. Source: http://my.champlain.edu/public/community.book.program from Columbia. She lives in New York City. Otsuka is one of the winners of the Sixth Annual Asian Ameri- Author’s Biography & Quote Source: http://www.asiasource.org/arts/julieotsuka.cfm can Literary Awards and was honored at the Asia Society on December 8, 2003. Praises For the Book Source: http://www.randomhouse.com/anchor/catalog/display.pperl? isbn=9780385721813 Otsuka, Julie. When the Emperor Was Divine. NY: Anchor Books, 2002. Cover design by John Gall "I wanted to write a novel about real people... their experience is universal not only for Japanese Ameri- IPSWICH PUBLIC LIBRARY cans, but for people of any ethnic group. All through- 25 North Main Street This is the fourth year of our town-wide out history people have been rounded up and sent Ipswich, MA 01938 reading program. -

Migrating Fictions

MIGRATING FICTIONS Migrating Fictions Gender, Race, and Citizenship in U.S. Internal Displacements ABIGAIL G. H. MANZELLA THE OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS | COLUMBUS Copyright © 2018 by Abigail G. H. Manzella. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Manzella, Abigail G. H., author. Title: Migrating fictions : gender, race, and citizenship in U.S. internal displacements / Abigail G. H. Manzella. Description: Columbus : The Ohio State University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017036404 | ISBN 9780814213582 (cloth ; alk. paper) | ISBN 0814213588 (cloth ; alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: American fiction—20th century—History and criticism. | Migration, Internal, in literature. | Race relations in literature. | Displacement (Psychology) in literature. | Refugees in literature. Classification: LCC PS379 .M295 2018 | DDC 813/.509355—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017036404 Cover design by Andrew Brozyna Text design by Juliet Williams Type set in Adobe Minion Pro Front cover images: (1) Jack Delano, “Group of Florida migrants on their way to Cranberry, New Jersey, to pick potatoes,” Near Shawboro, North Carolina. Library of Congress, July 1940. (2) Clem Albers, “Persons of Japanese ancestry arrive at the Santa Anita Assembly center from Santa Anita Assembly center from San Pedro, California. Evacuees lived at this center at the Santa Anita race track before being moved inland to relocation centers,” Arcadia, California. National Archives, April 5, 1942. Back cover image: Dorothea Lange, “Cheap auto camp housing for citrus workers,” Tulare County, California. National Archives, February 1940. Published by The Ohio State University Press The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka

When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka About the author Julie Otsuka was born in Palo Alto and studied art at Yale University. After pursuing a career as a painter, she turned to fiction at age 30. One of her short stories was included in Scribner's Best of the Fiction Workshops 1998, edited by Carol Shields. When the Emperor Was Divine is her first novel. About the book Julia Otsuka's quietly disturbing novel opens with a woman reading a sign in a post office window. It is Berkeley, California, the spring of 1942. Pearl Harbor has been attacked, the war is on, and though the precise message on the sign is not revealed, its impact on the woman who reads it is immediate and profound. It is, in many ways she cannot yet foresee, a sign of things to come. She readies herself and her two young children for a journey that will take them to the high desert plains of Utah and into a world that will shatter their illusions forever. They travel by train and gradually the reader discovers that all on board are Japanese American, that the shades must be pulled down at night so as not to invite rock-throwing, and that their destination is an internment camp where they will be imprisoned "for their own safety" until the war is over. With stark clarity and an unflinching gaze, Otsuka explores the inner lives of her main characters—the mother, daughter, and son—as they struggle to understand their fate and long for the father whom they have not seen since he was whisked away, in slippers and handcuffs, on the evening of Pearl Harbor. -

Julie Otsuka の描く「私たち」の物語

759 Julie Otsuka の描く「私たち」の物語 Julie Otsuka の描く「私たち」の物語 ― When the Emperor Was Divine と The Buddha in the Attic ― 桧 原 美 恵 1.日系アメリカ人の体験を描く文学と Julie Otsuka Julie Otsuka(1962 年生まれ)は、2002 年に When the Emperor Was Divine を、2011 年に The Buddha in the Attic を Knopf 社から出版した。両作品ともに、“the PEN/Faulkner Award”と、フ ランスの “Prix Femina Etranger” を受賞し、前者は “the Asian American Literary Award” をはじ め多くの賞を受け、後者も “the National Book Award” の候補作品として選ばれ、“the Langum Prize for American Historical Fiction” など、いくつもの賞を授与された。前者は 8 ヵ国語に翻訳さ れ、全米の 35 の大学において一年次の必読書となっている。後者は、18 ヵ国語に翻訳され、Library Journal 誌などでトップテンの傑作と評価されもした。 When the Emperor Was Divine は日系アメリカ人の収容所体験を描き、The Buddha in the Attic は日本からアメリカに写真花嫁として渡った女性たちの船上での思いや、新天地アメリカで遭遇す る苦しい生活体験とパールハーバー後の立退き体験が引き起こす彼女たちの心情描写を中心軸とし た物語である。 これまでに多くの日系アメリカ人作家たちが、アメリカにおける日系コミュニティでの実体験に 基づいた生活状況とそれから引き起こされる心情を作品世界で表してきた。収容所体験については、 人間の尊厳を奪われるほどの恥辱だと感じて、それを口にできない多くの日系人収容所経験者がい た。収容所体験を文字に表して作品化した人たち、すなわち Monica Sone(Nisei Daughter, 1953) や John Okada(No-No Boy, 1957)たちが登場するのは、1950 年代まで待たなければならなかった。 公民権運動の影響を受けて民族意識が高揚し、日系人コミュニティにおいて収容所体験の補償を求 めるリドレス運動が 1970 年代初頭に台頭し、やがて 1980 年代にかけて広まっていった。そのよう ななかで、1970 年代初期から Yoshiko Uchida(Journey to Topaz, 1971)や Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston(Farewell to Manzanar, 1973)、そして Mitsuye Yamada(Camp Notes and Other Poems, 1976)などが文学作品において自身の体験を表し始めた。また、収容所体験をもつ人々がその体験 を語りはじめた。このような、主として二世が実体験を基に作品を著している時期を経て、日本軍 によるパールハーバー襲撃から 50 年が経った「1991 年の 50 周年記念日以降、アメリカ文化のなか で、パールハーバーがますます大きな注目を集めるようになったと思われる」(Rosenberg 1)頃か ら、収容所体験のない日系アメリカ人が収容所を背景とした作品を描く傾向が見られるようになっ た。「21 世紀へ向かう世紀転換期のアメリカでは、第二次世界大戦に関する『回想ブーム』が喜んで -

Julie Otsuka's When the Emperor Was Divine, a Heart

Iulian Boldea, Cornel Sigmirean (Editors) MULTICULTURAL REPRESENTATIONS. Literature and Discourse as Forms of Dialogue Arhipelag XXI Press, Tîrgu Mureș, 2016 159 ISBN: 978-606-8624-16-7 Section: Literature JULIE OTSUKA’S WHEN THE EMPEROR WAS DIVINE, A HEART- WRENCHING EVACUEE’S DIARY Andreea Iliescu Senior Lecturer, PhD, University of Craiova Abstract: Julie Otsuka chronicles historical events, her narrative being defined by both a tone of emotional restraint and by a lack of fleshed-out protagonists. A host of succinctly described characters inhabit the novel, coming across as generic figures that embody the suffering of Japanese Americans’ communities. Claiming a place, being in constant pursuit of others’ acceptance as someone caught between cultures-neither here nor there-, driven by the urge to become vocal, facing, therefore, strenuous emotional dilemmas time and again, all the aforementioned reasons lead Julie Otsuka to undoubtedly jump at the opportunity of balancing views and triggering debates through her art. Keywords: literature as a catalyst, ethnicity, mainstream American society, assimilation demands. 1. Introduction Writing empowers Julie Otsuka to reconcile past and present, thus forging a more inspiring future, and it also helps her to articulate an unmistakable identity over time. At the core of her writing lies the determination to come to grips with both the mainstream American society and the ethnic background. Furthermore, throughout the literary work under discussion, writing acquires various meanings, to the point where the novel engages readers in a different analysis relative to the manner in which ideas might transgress time and space frames. In the light of this, I argue that first, second and third, writing is assigned the primary role in the novel.