Failure's Frontier: Ambition, Indebtedness, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clay Family

rilson Oub Publications NUMBER FOURTEEN The Clay Family PART FIRST The Mother of Henry Clay PART SECOND The Genealogy of the Clays BY Honorable Zachary F. Smith —AND- Mrs. Mary Rogers Clay Members of The Filson Club \ 1 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/clayfamilysmit Honorable HENRY CLAY. FILSON CLUB PUBLICATIONS NO. 14 The Clay Family PART FIRST The Mother of Henry Clay Hon. ZACHARY F. SMITH Member of The Filson Club PART SECOND The Genealogy of the Clays BY Mrs. MARY ROGERS CLAY Member of The Filson Club Louisville, Kentucky JOHN P. MORTON AND COMPANY Ttrinturs to TItb Filson ffiluh 1899 COPYRIGHTED BY THE FILSON CLUB 1899 PREFACE FEW elderly citizens yet living knew Henry Clay, A the renowned orator and statesman, and heard him make some of his greatest speeches. Younger per- sons who heard him not, nor saw him while living, have learned much of him through his numerous biog- raphers and from the mouths of others who did know him. Most that has been known of him, however, by either the living or the dead, has concerned his political career. For the purpose of securing votes for him among the masses in his candidacy for different offices he has been represented by his biographers as being of lowly origin in the midst of impecunious surroundings. Such, however, was not the condition of his early life. He was of gentle birth, with parents on both sides possessing not only valuable landed estates and numer- ous slaves, but occupying high social positions. -

Philadelphia and the Southern Elite: Class, Kinship, and Culture in Antebellum America

PHILADELPHIA AND THE SOUTHERN ELITE: CLASS, KINSHIP, AND CULTURE IN ANTEBELLUM AMERICA BY DANIEL KILBRIDE A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In seeing this dissertation to completion I have accumulated a host of debts and obligation it is now my privilege to acknowledge. In Philadelphia I must thank the staff of the American Philosophical Society library for patiently walking out box after box of Society archives and miscellaneous manuscripts. In particular I must thank Beth Carroll- Horrocks and Rita Dockery in the manuscript room. Roy Goodman in the Library’s reference room provided invaluable assistance in tracking down secondary material and biographical information. Roy is also a matchless authority on college football nicknames. From the Society’s historian, Whitfield Bell, Jr., I received encouragement, suggestions, and great leads. At the Library Company of Philadelphia, Jim Green and Phil Lapansky deserve special thanks for the suggestions and support. Most of the research for this study took place in southern archives where the region’s traditions of hospitality still live on. The staff of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History provided cheerful assistance in my first stages of manuscript research. The staffs of the Filson Club Historical Library in Louisville and the Special Collections room at the Medical College of Virginia in Richmond were also accommodating. Special thanks go out to the men and women at the three repositories at which the bulk of my research was conducted: the Special Collections Library at Duke University, the Southern Historical Collection of the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and the Virginia Historical Society. -

1 the Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library

The Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library Bibliography: with Annotations on marginalia, and condition. Compiled by Christian Goodwillie, 2017. Coastal Affair. Chapel Hill, NC: Institute for Southern Studies, 1982. Common Knowledge. Duke Univ. Press. Holdings: vol. 14, no. 1 (Winter 2008). Contains: "Elizabeth Fox-Genovese: First and Lasting Impressions" by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. Confederate Veteran Magazine. Harrisburg, PA: National Historical Society. Holdings: vol. 1, 1893 only. Continuity: A Journal of History. (1980-2003). Holdings: Number Nine, Fall, 1984, "Recovering Southern History." DeBow's Review and Industrial Resources, Statistics, etc. (1853-1864). Holdings: Volume 26 (1859), 28 (1860). Both volumes: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Both volumes badly water damaged, replace. Encyclopedia of Southern Baptists. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1958. Volumes 1 through 4: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Volume 2 Text block: scattered markings. Entrepasados: Revista De Historia. (1991-2012). 1 Holdings: number 8. Includes:"Entrevista a Eugene Genovese." Explorations in Economic History. (1969). Holdings: Vol. 4, no. 5 (October 1975). Contains three articles on slavery: Richard Sutch, "The Treatment Received by American Slaves: A Critical Review of the Evidence Presented in Time on the Cross"; Gavin Wright, "Slavery and the Cotton Boom"; and Richard K. Vedder, "The Slave Exploitation (Expropriation) Rate." Text block: scattered markings. Explorations in Economic History. Academic Press. Holdings: vol. 13, no. 1 (January 1976). Five Black Lives; the Autobiographies of Venture Smith, James Mars, William Grimes, the Rev. G.W. Offley, [and] James L. Smith. Documents of Black Connecticut; Variation: Documents of Black Connecticut. 1st ed. ed. Middletown: Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1971. Badly water damaged, replace. -

South Carolina's Partisan

SOWING THE SEEDS OF DISUNION: SOUTH CAROLINA’S PARTISAN NEWSPAPERS AND THE NULLIFICATION CRISIS, 1828-1833 by ERIKA JEAN PRIBANIC-SMITH A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication and Information Sciences in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2010 Copyright Erika Jean Pribanic-Smith, 2010 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Ultimately the first state to secede on the eve of the Civil War, South Carolina erupted in controversy following the 1828 passage of an act increasing duties on foreign imports for the protection of domestic industry. Most could agree that the tariff was unconstitutional, unequal in that it benefited the industrial North more than the agrarian South, and oppressive to plantation states that had to rely on expensive northern goods or foreign imports made more costly by the duties. Factions formed, however, based on recommended means of redress. Partisan newspapers of that era became vocal supporters of one faction or the other. What became the Free Trade Party by the end of the Nullification Crisis began as a loosely-organized group that called for unqualified resistance to what they perceived as a gross usurpation of power by the federal government. The Union Party grew out of a segment of the population that was loyal to the government and alarmed by their opposition’s disunion rhetoric. Strong at the start due to tariff panic and bolstered by John C. Calhoun’s “South Carolina Exposition and Protest,” the Free Trade Party lost ground when the Unionists successfully turned their overzealous disunion language against them in the 1830 city and state elections. -

Valley Leaves

TENNESSEE VALLEY GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY Valley Leaves Volume 51, Issues 1-2 Fall 2016 Publications Available for Purchase Back Issues Volumes 1 through 13 (1966-1980) available on CD $ 10 per volume Note: If ordering Vol. 4, there are three issues. The fourth is a special edition of Issue 2; which sells for $12 separately. Volumes 14 through 35 (1980-2001) $10 per volume Volumes 36 through 47 (2001-2013) $25 per volume Note: For Volumes 1-46, each volume usually contains four issues. Parting with Volume 47, two combined issues are published Other Publications for Sale Ancestor Charts [Volumes 1,2,3 & 4] 5 generation charts full name index $15.00/volume Minutes of the Baptist Church of Jesus Christ on Paint Rock River and Larkin Fork, Jackson Co., AL. (96 pages, full name index) Anne Beason Gahan © 1991 $20.00 Lawrence Co., AL 1820 State Census, 42 pages, TVGS © $ 15.00 Enumeration of the Moon Cemetery and Byrd Cemetery, Owens Cross Roads, Madison Co, AL.Carla Deramus © 1996 reprinted 2003 $15.00 1907 Confederate Census of Limestone, Morgan & Madison Counties Alabama, 52 pages, Dorothy Scott Johnson, © 1981 $12.00 Death Notices From Limestone Co., AL., Newspapers, 1828-1891, Eulalia Yancey Wellden,© 1986, 2003 $25.00 1840 Limestone County Census, 2nd Edition, 66 pages [retyped], Eulalia Yancy Wellde $20.00 Early History of Madison County, Valley Leaves, Special Edition, A Companion to Vol. 4. TVGS, © December 1969 $ 15.00 Index to Wills of Madison County, AL. 1808-1900, 36 pages, A. Ezell Terry, © 1977 $12.00 Marriages of Morgan County, AL 1818-1896, 305 pages, Elbert Minter © 1986 $28.00 Battle of Buckhorne Tavern, Souvenir Program of the 1996 Re-enactment $2.00 Map: Revolutionary War Soldiers and Patriots Buried in Madison County, AL. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

History of the U.S. Attorneys

Bicentennial Celebration of the United States Attorneys 1789 - 1989 "The United States Attorney is the representative not of an ordinary party to a controversy, but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern impartially is as compelling as its obligation to govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a case, but that justice shall be done. As such, he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer. He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor– indeed, he should do so. But, while he may strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain from improper methods calculated to produce a wrongful conviction as it is to use every legitimate means to bring about a just one." QUOTED FROM STATEMENT OF MR. JUSTICE SUTHERLAND, BERGER V. UNITED STATES, 295 U. S. 88 (1935) Note: The information in this document was compiled from historical records maintained by the Offices of the United States Attorneys and by the Department of Justice. Every effort has been made to prepare accurate information. In some instances, this document mentions officials without the “United States Attorney” title, who nevertheless served under federal appointment to enforce the laws of the United States in federal territories prior to statehood and the creation of a federal judicial district. INTRODUCTION In this, the Bicentennial Year of the United States Constitution, the people of America find cause to celebrate the principles formulated at the inception of the nation Alexis de Tocqueville called, “The Great Experiment.” The experiment has worked, and the survival of the Constitution is proof of that. -

Professional Communities in Alabama, from 1804 to 1861

OBJECTS OF CONFIDENCE AND CHOICE: PROFESSIONAL COMMUNITIES IN ALABAMA, 1804-1861 By THOMAS EDWARD REIDY JOSHUA D. ROTHMAN, COMMITTEE CHAIR GEORGE C. RABLE LAWRENCE F. KOHL JOHN M. GIGGIE JENNIFER R. GREEN A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2014 ! Copyright Thomas E. Reidy 2014 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Objects of Confidence and Choice considered the centrality of professional communities in Alabama, from 1804 to 1861. The dissertation highlighted what it meant to be a professional, as well as what professionals meant to their communities. The study examined themes of education, family, wealth patterns, slaveholding, and identities. This project defined professionals as men with professional degrees or licenses to practice: doctors, clergymen, teachers, and others. Several men who appeared here have been widely studied: William Lowndes Yancey, Josiah Nott, J. Marion Sims, James Birney, Leroy Pope Walker, Clement Comer Clay, and his son Clement Claiborne Clay. Others are less familiar today, but were leaders of their towns and cities. Names were culled from various censuses and tax records, and put into a database that included age, marital status, children, real property, personal property, and slaveholding. In total, the database included 453 names. The study also mined a rich vein of primary source material from the very articulate professional community. Objects of Confidence and Choice indicated that professionals were not a social class but a community of institution builders. In order to refine this conclusion, a more targeted investigation of professionals in a single antebellum Alabama town will be needed. -

The Supreme Court of Alabama—Its Cahaba Beginning, 1820–1825

File: MEADOR EIC PUBLISH.doc Created on: 12/6/2010 1:51:00 PM Last Printed: 12/6/2010 2:53:00 PM ALABAMA LAW REVIEW Volume 61 2010 Number 5 THE SUPREME COURT OF ALABAMA— ITS CAHABA BEGINNING, 1820–1825 ∗ Daniel J. Meador I. PROCEEDINGS IN HUNTSVILLE, 1819 ....................................... 891 II. THE FIRST SEAT OF STATE GOVERNMENT—CAHABA .................. 894 III. THE SUPREME COURT JUDGES IN THE CAHABA YEARS, 1820–1825 896 IV. THE SUPREME COURT’S BUSINESS IN THE CAHABA YEARS .......... 900 V. CONCLUSION .................................................................. 905 The Supreme Court of Alabama opened its first term on May 8, 1820 at Cahaba, the site designated as the new state’s first seat of government. The court was born then and there, but it had been conceived the previous year in Huntsville, then the territorial capital.1 I. PROCEEDINGS IN HUNTSVILLE, 1819 The movement toward statehood in the Alabama Territory, created in 1817 when Mississippi was admitted as a state, formally began in March 1819 with congressional passage of the Enabling Act. That Act authorized the people of the territory to adopt a constitution and enact laws providing for a state government. Pursuant to that Act, a convention of forty-four elected delegates from throughout the territory convened in Huntsville in July to draft a state constitution.2 Huntsville, located in the Tennessee Val- ∗ James Monroe Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Virginia; member, Alabama State Bar; dean University of Alabama Law School, 1966–1970; author of At Cahaba-From Civil War to Great Depression (Cable Publishing, 2009); President, Cahaba Foundation, Inc. 1. -

Trial Memorandum of President Donald J. Trump

IN PROCEEDINGS BEFORE THE UNITED STATES SENATE TRIAL MEMORANDUM OF PRESIDENT DONALD J. TRUMP Jay Alan Sekulow Pat A. Cipollone Stuart Roth Counsel to the President Andrew Ekonomou Patrick F. Philbin Jordan Sekulow Michael M. Purpura Mark Goldfeder Devin A. DeBacker Benjamin Sisney Trent J. Benishek Eric J. Hamilton Counsel to President Donald J. Trump Office of White House Counsel January 20, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 STANDARDS............................................................................................................................... 13 A. The Senate Must Decide All Questions of Law and Fact. .................................... 13 B. An Impeachable Offense Requires a Violation of Established Law that Inflicts Sufficiently Egregious Harm on the Government that It Threatens to Subvert the Constitution. .................................................................. 13 1. Text and Drafting History of the Impeachment Clause ............................ 14 2. The President’s Unique Role in Our Constitutional Structure .................. 17 3. Practice Under the Impeachment Clause .................................................. 18 C. The Senate Cannot Convict Unless It Finds that the House Managers Have Proved an Impeachable Offense Beyond a Reasonable Doubt. .................. 20 D. The Senate May Not Consider Allegations Not Charged in the Articles of Impeachment. .................................................................................................. -

Early History of Huntsville, Alabama, 1804-1870

r 334- .H9B5 ,,^^t-^^:t/.i•-^•:• A "^^^ ^' .5 -n^. o'^- ^' xV ^> .A' / . s ^ -^U a "^O- v^' .^^ ^^. .^^' .0 o^ ^, .^ A^ '>- V o5 -Tt/. "^ i-t-'^ -^' A. .y.„ N -/ . ,; i' .A O . o5 Xc :^'^' ^^.vA' ^b << ^^' '^ -l\'' •^oo^ v r 7"/-/-. I EARLY HISTORY OF HUNTSVILLE ALABAMA 1804 TO 1870 I I EARLY HISTORY OF HUNTSVILLE, ALABAMA 1804 TO 1870 With the Compliments of the Author REVISED 1916 MONTGOMERY, ALA. THE BROWN PRINTING CO. 1916 EARLY HISTORY OF HUNTSVILLE. ALABAMA 1804 TO 1870 BY EDWARD CHAMBERS BETTS 1909 '' REVISED 1916 MONTGOMERY, ALA. THE BROWN PRINTING CO. 1916 Hres Copyright. 1916 BY EDWARD CHAMBERS BETTS ^ 'CI.A'I4R190 NOV -I 1916 "VU) I ^ FOREWORD In the preparation of this work the author is largely indebted to the Department of Archives and History of Alabama, under the capable management of Dr. Thomas M. Owen, who con- tributed liberally of his time assisting in a search of the files and records of this Department. Especially is the author indebted for the aid received from the letters of Judge Thomas J. Taylor,* dealing with this subject. In its inception this work was not intended for, nor is it offered as, a literary efifort, but merely as a chronicle of his- torical facts and events dealing with Huntsville. In its prepa- ration, the author has taken care to record nothing within its pages for which his authority as to the source of information is not given. It has value only as a documentary record of facts and events gleaned chiefly from contemporaneous sources, and is as accurate as could be made after verification from all material at hand, which was necessarily very meager. -

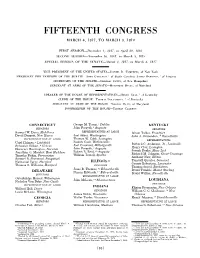

K:\Fm Andrew\11 to 20\15.Xml

FIFTEENTH CONGRESS MARCH 4, 1817, TO MARCH 3, 1819 FIRST SESSION—December 1, 1817, to April 20, 1818 SECOND SESSION—November 16, 1818, to March 3, 1819 SPECIAL SESSION OF THE SENATE—March 4, 1817, to March 6, 1817 VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES—DANIEL D. TOMPKINS, of New York PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE OF THE SENATE—JOHN GAILLARD, 1 of South Carolina; JAMES BARBOUR, 2 of Virginia SECRETARY OF THE SENATE—CHARLES CUTTS, of New Hampshire SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE SENATE—MOUNTJOY BAYLY, of Maryland SPEAKER OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES—HENRY CLAY, 3 of Kentucky CLERK OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DOUGHERTY, 4 of Kentucky SERGEANT AT ARMS OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS DUNN, of Maryland DOORKEEPER OF THE HOUSE—THOMAS CLAXTON CONNECTICUT George M. Troup, 7 Dublin KENTUCKY 8 SENATORS John Forsyth, Augusta SENATORS Samuel W. Dana, Middlesex REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Isham Talbot, Frankfort David Daggett, New Haven Joel Abbot, Washington John J. Crittenden, 15 Russellville REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE Thomas W. Cobb, Lexington REPRESENTATIVES 5 Zadock Cook, Watkinsville Uriel Holmes, Litchfield Richard C. Anderson, Jr., Louisville 6 Joel Crawford, Milledgeville Sylvester Gilbert, Hebron Henry Clay, Lexington Ebenezer Huntington, Norwich John Forsyth, 9 Augusta Robert R. Reid, 10 Augusta Joseph Desha, Mays Lick Jonathan O. Moseley, East Haddam Richard M. Johnson, Great Crossings Timothy Pitkin, Farmington William Terrell, Sparta Anthony New, Elkton Samuel B. Sherwood, Saugatuck Tunstall Quarles, Somerset Nathaniel Terry, Hartford ILLINOIS 11 George Robertson, Lancaster Thomas S. Williams, Hartford SENATORS Thomas Speed, Bardstown Jesse B. Thomas, 12 Edwardsville David Trimble, Mount Sterling DELAWARE Ninian Edwards, 13 Edwardsville SENATORS David Walker, Russellville REPRESENTATIVE AT LARGE Outerbridge Horsey, Wilmington John McLean, 14 Shawneetown LOUISIANA Nicholas Van Dyke, New Castle SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES AT LARGE INDIANA Willard Hall, Dover Eligius Fromentin, New Orleans SENATORS 16 Louis McLane, Wilmington William C.