The Supreme Court of Alabama—Its Cahaba Beginning, 1820–1825

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting Rights in Alabama 1982-2006

VOTING RIGHTS IN ALABAMA 1982-2006 A REPORT OF RENEWTHEVRA.ORG PREPARED BY JAMES BLACKSHER, EDWARD STILL, NICK QUINTON, CULLEN BROWN AND ROYAL DUMAS JULY 2006 VOTING RIGHTS IN ALABAMA, 1982-2006 1 2 3 4 5 JAMES BLACKSHER , EDWARD STILL , NICK QUINTON , CULLEN BROWN , ROYAL DUMAS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to the Voting Rights Act 1 I. The Temporary Provisions of the Voting Rights Act that Apply to Alabama 1 II. Alabama Demographics 2 III. A Brief History of Pre-1982 Voting Discrimination in Alabama 3 IV. Voting Discrimination in Alabama Since 1982 5 A. Summary of enforcement of the temporary provisions 6 1. Section 5 6 2. Observer Provisions 7 B. Intentional Discrimination in Pollworker Appointment 8 C. Intentional Discrimination in Methods of Electing Local Bodies 9 D. Intentional Discrimination in Annexations 16 E. Hale County: An Example of the Voting Rights Act at Work 17 F. The Voting Rights Act and Congressional and Legislative 20 Redistricting in Alabama G. The Persistence of Racially Polarized Voting 24 Conclusion 29 1 Civil Rights Litigator 2 Civil Rights Litigator 3 University of Alabama student 4 University of Alabama student 5 University of Alabama student INTRODUCTION TO THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT For decades, Alabama has been at the center of the battle for voting rights equality. Several of the pre-1965 voting cases brought by the Department of Justice and private parties were in Alabama. The events of Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 served as a catalyst for the introduction and passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. -

The Clay Family

rilson Oub Publications NUMBER FOURTEEN The Clay Family PART FIRST The Mother of Henry Clay PART SECOND The Genealogy of the Clays BY Honorable Zachary F. Smith —AND- Mrs. Mary Rogers Clay Members of The Filson Club \ 1 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from The Institute of Museum and Library Services through an Indiana State Library LSTA Grant http://www.archive.org/details/clayfamilysmit Honorable HENRY CLAY. FILSON CLUB PUBLICATIONS NO. 14 The Clay Family PART FIRST The Mother of Henry Clay Hon. ZACHARY F. SMITH Member of The Filson Club PART SECOND The Genealogy of the Clays BY Mrs. MARY ROGERS CLAY Member of The Filson Club Louisville, Kentucky JOHN P. MORTON AND COMPANY Ttrinturs to TItb Filson ffiluh 1899 COPYRIGHTED BY THE FILSON CLUB 1899 PREFACE FEW elderly citizens yet living knew Henry Clay, A the renowned orator and statesman, and heard him make some of his greatest speeches. Younger per- sons who heard him not, nor saw him while living, have learned much of him through his numerous biog- raphers and from the mouths of others who did know him. Most that has been known of him, however, by either the living or the dead, has concerned his political career. For the purpose of securing votes for him among the masses in his candidacy for different offices he has been represented by his biographers as being of lowly origin in the midst of impecunious surroundings. Such, however, was not the condition of his early life. He was of gentle birth, with parents on both sides possessing not only valuable landed estates and numer- ous slaves, but occupying high social positions. -

2019 HAI Annual Data Report

2019 HAI Annual Data Report December 30, 2020 The final 2019 HAI report will be posted at a later date. The data on the following pages has been approved by all acute and critical access facilities. Alabama Hospitals 2019 CAUTI Report for Review Includes data from medical wards, surgical wards, medical/surgical wards, and adult and pediatric critical care units. Facilities without these units report data from mixed age/mixed acuity wards. Ratio of Hospital Number of Observed to Performance Volume of Number of Type Region Hospital Name Catheter Expected Compared to Hospital CAUTIs Days Infections National (SIR) Performance CAUTI State State of Alabama N/A 305 405,574 0.632 Better* CAUTI Southeast Andalusia Health Medium 0 2,099 0 Similar CAUTI North Athens Limestone Hospital Medium 3 3,370 1.671 Similar CAUTI Southwest Atmore Community Hospital Medium 0 588 N/A - CAUTI Central Baptist Medical Center East High 9 5,972 1.447 Similar CAUTI Central Baptist Medical Center South High 33 16,880 1.115 Similar CAUTI West Bibb Medical Center Medium 1 418 N/A - CAUTI Birmingham Brookwood Medical Center Medium 6 5,439 1.001 Similar CAUTI Central Bullock County Hospital Low 0 54 N/A Similar CAUTI Birmingham Children's Health System Medium 3 1,759 1.046 Similar CAUTI Southwest Choctaw General Hospital Low 0 235 N/A - CAUTI Northeast Citizens Baptist Medical Center Medium 1 1,312 N/A - CAUTI Northeast Clay County Hospital Medium 1 337 N/A - CAUTI Central Community Hospital Medium 0 502 N/A - CAUTI Northeast Coosa Valley Medical Center Medium 0 2,471 0 Similar CAUTI Central Crenshaw Community Hospital Low 2 284 N/A - CAUTI North Crestwood Medical Center Medium 1 4,925 0.291 Similar CAUTI North Cullman Regional Medical Center High 3 7,042 0.598 Similar CAUTI Southwest D.W. -

Social Studies

201 OAlabama Course of Study SOCIAL STUDIES Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education • Alabama State Department of Education For information regarding the Alabama Course of Study: Social Studies and other curriculum materials, contact the Curriculum and Instruction Section, Alabama Department of Education, 3345 Gordon Persons Building, 50 North Ripley Street, Montgomery, Alabama 36104; or by mail to P.O. Box 302101, Montgomery, Alabama 36130-2101; or by telephone at (334) 242-8059. Joseph B. Morton, State Superintendent of Education Alabama Department of Education It is the official policy of the Alabama Department of Education that no person in Alabama shall, on the grounds of race, color, disability, sex, religion, national origin, or age, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program, activity, or employment. Alabama Course of Study Social Studies Joseph B. Morton State Superintendent of Education ALABAMA DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION STATE SUPERINTENDENT MEMBERS OF EDUCATION’S MESSAGE of the ALABAMA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION Dear Educator: Governor Bob Riley The 2010 Alabama Course of Study: Social President Studies provides Alabama students and teachers with a curriculum that contains content designed to promote competence in the areas of ----District economics, geography, history, and civics and government. With an emphasis on responsible I Randy McKinney citizenship, these content areas serve as the four Vice President organizational strands for the Grades K-12 social studies program. Content in this II Betty Peters document focuses on enabling students to become literate, analytical thinkers capable of III Stephanie W. Bell making informed decisions about the world and its people while also preparing them to IV Dr. -

Alabama” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 46, folder “4/3/76 - Alabama” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 46 of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library I THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON THE PRESIDENT'S BRIEFING BOOK QUESTIONS AND ANSWERS ************************* ALABAMA MAY 3, 1976 ************************* ALABAMA State Profile Alabama is called the "Yellowhanuner state because of its state bird, the "Cotton state" because of its chief agricultural product and the "Heart of Dixie" because of its location. The total area of Alabama is 51,609 square miles, of which 549 square miles are inland water surface. It is the 29th state of the union is size. The state capital is Montgomery and the state entered the union on December 14, 1819, as the 22nd state. The southern pine has been adopted as the state's official tree and the camellia as the official flower. -

Sense of Place in Appalachia. INSTITUTION East Tennessee State Univ., Johnson City

DOCUMENT. RESUME ED 313 194 RC 017 330 AUTHOR Arnow, Pat, Ed. TITLE Sense of Place in Appalachia. INSTITUTION East Tennessee State Univ., Johnson City. Center for Appalachian Sttdies and Services. PUB DATE 89 NOTE 49p.; Photographs will not reproduce well. AVAILABLE FROMNow and Then, CASS, Box 19180A, ETSU, Johnson City, TN 37614-0002 ($3.50 each; subscription $9.00 individual and $12.00 institution). PUB TYPE Collected Works -Serials (022) -- Viewpoints (120) -- Creative Works (Literature,Drama,Fine Arts) (030) JOURNAL CIT Now and Then; v6 n2 Sum 1989 EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Essays; Interviews; *Novels; Photographs; Poetry; *Regional Attitudes; Regional Characteristics; *Rural Areas; Short Stories IDENTIFIERS *Appalachia; Appalachian Literature; Appalachian People; *Place Identity; Regionalism; Rural Culture ABSTRACT This journal issue contains interviews, essays, short stc-ies, and poetry focusing on sense of place in Appalachia. In iLterviews, author Wilma Dykeman discussed past and recent novels set in Appalachia with interviewer Sandra L. Ballard; and novelist Lee Smith spoke with interviewer Pat Arnow about how Appalachia has shaped her writing. Essays include "Eminent Domain" by Amy Tipton Gray, "You Can't Go Home If You Haven't Been Away" by Pauline Binkley Cheek, and "Here and Elsewhere" by Fred Waage (views of regionalism from writers Gurney Norman, Lou Crabtree, Joe Bruchac, Linda Hogan, Penelope Schott and Hugh Nissenson). Short stories include "Letcher" by Sondra Millner, "Baptismal" by Randy Oakes, and "A Country Summer" by Lance Olsen. Poems include "Honey, You Drive" by Jo Carson, "The Widow Riley Tells It Like It Is" by P. J. Laska, "Words on Stone" by Wayne-Hogan, "Reeling In" by Jim Clark, "Traveler's Rest" by Walter Haden, "Houses" by Georgeann Eskievich Rettberg, "Seasonal Pig" by J. -

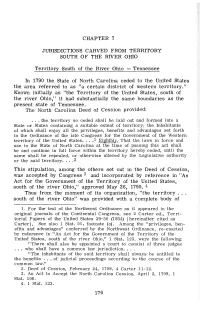

Chapter 7 Jurisdictions Carved from Territory

CHAPTER 7 JURISDICTIONS CARVED FROM TERRITORY SOUTH OF THE RIVER OHIO Territory South of the River Ohio - Tennessee In 1790 the State of North Carolina ceded to the United States the area referred to as "a certain district of western territory." Known initially as "the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," it had substantially the same boundaries as the present state of Tennessee. The North Carolina Deed of Cession provided: ... the territory so ceded shall be laid out and formed into a State or States containing a suitable extent of territory; the Inhabitants of which shall enjoy all the privileges, benefits and advantages set forth in the Ordinance of the late Congress for the Government of the Western territory of the United States ... .1 Eighthly, That the laws in force and use in the State of North Carolina at the time of passing this act shall be and continue in full force within the territory hereby ceded, until the same shall be repealed, or otherwise altered by the Legislative authority or the said territory ....2 This stipulation, among the others set out in the Deed of Cession, was accepted by Congress 3 and incorporated by reference in "An Act for the Government of the Territory of the United States, south of the river Ohio," approved May 26, 1790. 4 Thus from the moment of its organization, "the territory . south of the river Ohio" was provided with a complete body of 1. For the text of the Northwest Ordinance as it appeared in the original journals of the Continental Congress, see 2 Carter ed., Terri torial Papers of the United States 39-50 (1934) [hereinafter cited as Carter]. -

Alabama Office of the Attorney General Functional Analysis & Records Disposition Authority

Alabama Office of the Attorney General Functional Analysis & Records Disposition Authority Revision Presented to the State Records Commission April 24, 2019 Table of Contents Functional and Organizational Analysis of the Alabama Office of the Attorney General .... 3 Sources of Information ................................................................................................................ 3 Historical Context ....................................................................................................................... 3 Agency Organization ................................................................................................................... 3 Agency Function and Subfunctions ............................................................................................ 4 Records Appraisal of the Alabama Office of the Attorney General ........................................ 7 Temporary Records ..................................................................................................................... 7 Permanent Records .................................................................................................................... 11 Permanent Records List ............................................................................................................ 15 Alabama Office of the Attorney General Records Disposition Authority ............................. 16 Explanation of Records Requirements ...................................................................................... 16 Records -

3. Status of Delegates and Resident Commis

Ch. 7 § 2 DESCHLER’S PRECEDENTS § 2.24 The Senate may, by reiterated that request for the du- unanimous consent, ex- ration of the 85th Congress. change the committee senior- It was so ordered by the Senate. ity of two Senators pursuant to a request by one of them. On Feb. 23, 1955,(6) Senator § 3. Status of Delegates Styles Bridges, of New Hamp- and Resident Commis- shire, asked and obtained unani- sioner mous consent that his position as ranking minority member of the Delegates and Resident Com- Senate Armed Services Committee missioners are those statutory of- be exchanged for that of Senator Everett Saltonstall, of Massachu- ficers who represent in the House setts, the next ranking minority the constituencies of territories member of that committee, for the and properties owned by the duration of the 84th Congress, United States but not admitted to with the understanding that that statehood.(9) Although the persons arrangement was temporary in holding those offices have many of nature, and that at the expiration of the 84th Congress he would re- 9. For general discussion of the status sume his seniority rights.(7) of Delegates, see 1 Hinds’ Precedents In the succeeding Congress, on §§ 400, 421, 473; 6 Cannon’s Prece- Jan. 22, 1957,(8) Senator Bridges dents §§ 240, 243. In early Congresses, Delegates when Senator Edwin F. Ladd (N.D.) were construed only as business was not designated to the chairman- agents of chattels belonging to the ship of the Committee on Public United States, without policymaking Lands and Surveys, to which he had power (1 Hinds’ Precedents § 473), seniority under the traditional prac- and the statutes providing for Dele- tice. -

Membership List

ALABAMA 811 MEMBERSHIP LIST AT&T/D Bright House Networks – Birmingham AT&T/T Bright House Networks – Eufaula & Wetumpka AGL Resources Brindlee Mountain Telephone Company Air Products & Chemicals Brookside, Town of Alabama Department of Transportation Buckeye Partners LP Alabama Gas Corporation Buhl, Elrod & Holman Water Authority Alabama Power Company Butler, Town of Utilities Board Alabama Wastewater Systems, LLC Cable Alabama Corporation Alabaster, City of Cable One Alabaster Water Board Cable Options AlaTenn Pipeline Company Calera Gas, LLC Albertville Municipal Utilities Board Calera Water & Gas Board Alexander City, City of Camellia Communications American Midstream Camp Hill, Town of American Traffic Solutions Canadian National Railway American Water Carbon Hill Housing Authority Andalusia Utilities Board Carbon Hill Utilities Board Anniston Water Works and Sewer Board Carroll’s Creek Water Authority Arapaho Communications, LP Cave Spring, City of Ardmore Telephone Central Alabama Electric Cooperative Arlington Properties Central Talladega County Water District Ashton Place Apartments Central Water Works Atlas Energy Centreville Water Athens Utilities, City of CenturyTel of Alabama Auburn Water Works Board, City of Charter Communications of Alabama Baldwin County Commission Charter Communications – Lanett Baldwin County EMC Cherokee Water and Gas Department Baldwin County Sewer Service Childersburg Water, Sewer & Gas Board Bakerhill Water Authority Children’s of Alabama Bay Gas Storage Company, Inc. Chilton Water Authority Bayou La Batre Utilities CITGO Petroleum Corporation Bear Creek/Hackleburg Housing Authority Clarke-Mobile Counties Gas District Beauregard Water Authority Clayton Housing Authority Belforest Water System Cleburne County Water Authority Berry, Town of Coffee County Water Authority Berry Housing Authority Coker Water Authority, Inc. Bessemer Water Colbert County Rural Water System Beulah Utilties District Colonial Pipeline Bioflow – Russell Lands, Inc. -

Vs - CHRISTOPHER GORDY, Warden, Donaldson Correctional Facility, and CYNTHIA STEWART, Warden, Holman Correctional Facility, Respondents

No. 19- IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES MICHAEL BRANDON SAMRA, Petitioner - vs - CHRISTOPHER GORDY, Warden, Donaldson Correctional Facility, and CYNTHIA STEWART, Warden, Holman Correctional Facility, Respondents ON PETITION FOR AN ORIGINAL WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS IN A CAPITAL CASE APPENDIX Volume 1 STEVEN R. SEARS ALAN M. FREEDMAN 655 Main Street Counsel of Record P.O. Box 4 CHRISTOPHER KOPACZ Montevallo, AL 35115 Midwest Center for Justice, Ltd. (205) 665-1211 P.O. Box 6528 [email protected] Evanston, IL 60204 (847) 492-1563 N. JOHN MAGRISSO (pro bono) [email protected] Attorney-At-Law 525 Florida St., Ste. 310 Baton Rouge, LA 70801 (225) 338-0235 [email protected] Counsel for Petitioner APPENDIX Appendix A Order of the Alabama Supreme Court setting execution date of May 16, 2019 (April 11, 2019) Appendix B State of Alabama’s motion to set an execution date (March 20, 2019) Appendix C Samra’s objection to the State’s motion to set an execution date (March 26, 2019) Appendix D State of Alabama’s response to Samra’s objection to the State’s motion to set an execution date (April 1, 2019) Appendix E Samra’s reply to the State’s motion to set an execution date (April 2, 2019) Appendix F Samra’s second successive state Rule 32 post-conviction petition, which raises Eighth Amendment claim (March 26, 2019) Appendix G Order of the Shelby County Circuit Court dismissing Samra’s second successive state Rule 32 post-conviction petition (April 10, 2019) Appendix H Samra’s re-filed second successive state Rule 32 post-conviction petition, which raises Eighth Amendment claim (April 29, 2019) Appendix I Samra’s motion for a stay of execution in the Alabama Supreme Court (April 29, 2019) Appendix J Samra’s motion for a stay of execution in the Shelby County Circuit Court (April 29, 2019) Appendix K Opinion of the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals affirming Samra’s conviction and sentence, Samra v. -

The Abbhs Newsletter Alabama Bench and Ba R Historical Society

May—June 2021 THE ABBHS NEWSLETTER ALABAMA BENCH AND BA R HISTORICAL SOCIETY From The President When, in 1993, my staff and I were called upon to prepare a plan for a judicial history program for the new Judicial Building, a whole new world was opened to me. A world that I previously did not know existed. In that world, Alabama was first, not last: in that world, Alabama's first constitution was a model for the Nation; in that world, Alabama adopted the first code of ethics for lawyers in the United States which, like the 1819 Constitution, became a model for the Nation; in that world, Alabama's Supreme Court was considered "long the ranking Supreme Court in the South”; and, in that world, Alabama's court system, under the leadership of Chief Justice Howell Heflin, became the most modern in America. These facts are seldom remembered in Alabama history textbooks, yet their impact on Alabama were tremen- dous. Twenty-eight years later, we are still exploring and discovering our legal history and trying to understand where we came from, how we got there, and where we are going next. As Robert Penn Warren said, "History cannot give us a program for the future, but it can give us a fuller understanding of ourselves, and of our common humanity, so that we can better face the future." So, as a step toward this self- understanding, I invite you to join the Alabama Bench and Bar Historical Society, a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of Inside This Issue: the state's judicial and legal system and to making the citizens of the state more knowledgeable about the state's courts and their place in Alabama and United States history.