(2013) 31 Windsor Y B Access Just 15 RACIALIZED in JUSTICE: THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2011 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium Panel with Cecil Foster

1 2011 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium Panel with Cecil Foster Writing Jazz: Gesturing Towards the Possible Interview conducted by Paul Watkins Transcribed by Elizabeth Johnstone Edited by Paul Watkins PW: So, this is the morning plenary. It’s more of an interview, a discussion of wits, somewhat dialogic, with Dr. Cecil Foster, who is a Canadian novelist. You may also know him as an essayist, journalist, and scholar. He was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, where he began working for the Caribbean News Agency. You can read his autobiography, which was published around 1998 and is called Island Wings, which describes his experience of growing up in Barbados and eventually emigrating to Canada, which he did in 1979. He worked for the Toronto Star, as well as the Globe and Mail. He was also a special advisor to Ontario’s Ministry of Culture. His most recent books, Where Race Does Not Matter, and Blackness and Modernity, explore the potentials for multiculturalism in Canada. Currently he is an associate professor of Sociology here at the University of Guelph, and hopefully today we’ll talk about multiculturalism, as well as improvisation, and how those intersections may relate to his own writing process. Without further ado I introduce Dr. Cecil Foster. CF: Good morning and let me say a special hello to all of my friends and colleagues, and people that will become friends and colleagues. It certainly is a pleasure to be here. I rather enjoy being here at Guelph. I have now gone through the ranks from assistant, to associate, to full professor, to end up being, one of the, I hope Ajay would consider me to be a writer. -

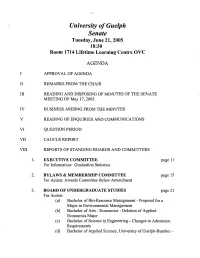

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

Program Guide a Festival for Readers and Writers

PROGRAM GUIDE A FESTIVAL FOR READERS AND WRITERS SEPTEMBER 25 – 29, 2019 HOLIDAY INN KINGSTON WATERFRONT penguinrandomca penguinrandomhouse.ca M.G. Vassanji Anakana Schofield Steven Price Dave Meslin Guy Gavriel Kay Jill Heinerth Elizabeth Hay Cary Fagan Michael Crummey KINGSTON WRITERSFEST PROUD SPONSOR OF PROUD SPONSOR OF KINGSTON WRITERSFEST Michael Crummey Cary Fagan Elizabeth Hay FULL PAGEJill Heinerth AD Guy Gavriel Kay Dave Meslin Steven Price Anakana Schofield M.G. Vassanji penguinrandomhouse.ca penguinrandomca Artistic Director's Message ow to sum up a year’s activity in a few paragraphs? One Hthing is for sure; the team has not rested on its laurels after a bang-up tenth annual festival in 2018. We’ve focussed our sights on the future, and considered how to make our festival more diverse, intriguing, relevant, inclusive and welcoming of those who don’t yet know what they’ve been missing, and those who may have felt it wasn’t a place for them. To all newcomers, welcome! We’ve programmed the most diverse festival yet. It wasn’t hard to fnd a range of stunning new writers in all genres, and seasoned writers with powerful new works. We’ve included the stories of women, the stories of Indigenous writers, Métis writers, writers of different experiences, cultural backgrounds, and orientations. Our individual and collective experience and understanding are sure to be enriched by these fresh perspectives, and new insights into the past. We haven’t forgotten our roots in good story-telling, presenting a variety of uplifting, entertaining, and thought-provoking fction and non-fction events. -

Multiculturalism As Transformative?

Multiculturalism as Transformative? Paul Gingrich Department of Sociology and Social Studies University of Regina [email protected] Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Canadian Sociology and Anthropology Association, York University, Toronto, May 30, 2006 Abstract The practice of multiculturalism can be a way for a diverse society to transform itself. By providing opportunities for all members of society to participate in social life and employing principles of multiculturalism such as equality, respect, and harmony, a society can become more socially just. Multiculturalism is not always thought of this way, and is often considered a means of preserving cultures, emphasizing difference, and separating people from each other. In this paper, I explore the possibility that multiculturalism provides a means of social transformation in a more socially just direction and provide evidence that some Canadians think of multiculturalism this way. That is, some consider it as a framework for working together to create a society that reduces barriers to participation by ending discriminatory treatment of some members and providing an opportunity for all members of the society to participate more fully in social life. The data I employ come from analysis of a student survey I conducted, from some national surveys, and from official statements about multiculturalism. The frameworks I use for organizing these data are those provided by Nancy Fraser and Cecil Foster. Fraser focuses on the dual issues of redistribution and recognition as distinct, but interlocking, dimensions of social justice. For Fraser, the criterion for a socially just transformation is parity of participation. Cecil Foster explores the possibility that multiculturalism has presented Canada with an opportunity that it should not ignore. -

Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Michigan Tech Publications 12-2019 Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois Laura Walikainen Rouleau Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Sarah Fayen Scarlett Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Steven A. Walton Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Timothy Scarlett Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Walikainen Rouleau, L., Scarlett, S. F., Walton, S. A., & Scarlett, T. (2019). Historic Resources Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois. Report for the National Park Service. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p/14692 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/michigantech-p Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Other Anthropology Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Midwest Archeological Center Lincoln, Nebraska Historic Resource Survey PULLMAN NATIONAL HISTORICAL MONUMENT Town of Pullman, Chicago, Illinois Dr. Laura Walikainen Rouleau Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett Dr. Steven A. Walton and Dr. Timothy J. Scarlett Michigan Technological University 31 December 2019 HISTORIC RESOURCE STUDY OF PULLMAN NATIONAL MONUMENT, Illinois Dr. Laura Walikainen Rouleau Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett Dr. Steven A. Walton and Dr. Timothy J. Scarlett Department of Social Sciences Michigan Technological University Houghton, MI 49931 Submitted to: Dr. Timothy M. Schilling Midwest Archeological Center, National Park Service 100 Centennial Mall North, Room 44 7 Lincoln, NE 68508 31 December 2019 Historic Resource Study of Pullman National Monument, Illinois by Laura Walikinen Rouleau Sarah F. -

The Case for Targeted Universalism

Directions Vol 6 No 2/ vol 6, no 2 Guest Editor/Éditorialiste invité Lesley A. Jacobs. CRRF staff / Personnel de la FCRR Daniel Chong Finance and Administration Dominique Etienne Communications, Social Development Alissa Lu Finance Assistant Anne Marrian Support and Knowledge Base Melanie Moussa-Elaraby Executive Secretary Aren Sarikyan Project Associate Production Management/Direction de la production CRRF Board of Directors Dominique Etienne Conseil d’administration de la FCRR Translator/Traductrice Dominique Nanoff Albert Lo, Chairperson Claudia Patricia Càceres (Richmond, British Columbia) (Québec, Québec) Design & Layout/Conception et mise en page Dominique Etienne Toni Silberman Marge Nainaar (Ottawa, Ontario) (Saskatchewan) The CRRF is making an effort to be environmentally friendly by going paperless. Mr. Ashraf Ghanem Kenny Blacksmith (Fredericton, New Brunswick) (Gloucester, Ontario) La FCRR cherche a limiter son impact environemental en minimisant son utilisation de papier. Lyn Q. Chow Hakim Feerasta (Calgary, Alberta) (Toronto, Ontario) Contact us / Veuillez communiquer avec la : Canadian Race Relations Foundation Roman Melnyk Peter Campbel 4576 Yonge Street, Suite 701 (Toronto, Ontario) (Mississauga, Ontario) Toronto, ON. M2N 6N4 Tel: 416-952-3501 Fax: 416-952-3326 Toll-free tel: 1-888-240-4936 Toll-free fax:1-888-399-0333 Nazanin Afshin-Jam Ayman Al-Yassini email: [email protected] (British Columbia) Executive Director www.crrf-fcrr.ca Mission… The Foundation is committed to building a national framework for the fight against racism in Canadian society. We will shed light on the causes and manifestations of racism; provide independent, outspoken national leadership; and act as a resource and facilitator in the pursuit of equity, fairness and social justice. -

Rooted Cosmopolitanism Canada and the World

Will Kymlicka and Kathryn Walker Rooted Cosmopolitanism Canada and the World Sample Material © 2012 UBC Press Contents Acknowledgments / vii 1 Rooted Cosmopolitanism: Canada and the World / 1 Will Kymlicka and Kathryn Walker Part 1: The Theory of Rooted Cosmopolitanism 2 Cosmopolitanism and Patriotism / 31 Kok-Chor Tan 3 A Defence of Moderate Cosmopolitanism and/or Moderate Liberal Nationalism / 47 Patti Tamara Lenard and Margaret Moore 4 Universality and Particularity in the National Question in Quebec / 69 Joseph-Yvon Thériault 5 Rooted Cosmopolitanism: Unpacking the Arguments / 87 Daniel Weinstock 6 We Are All Compatriots / 105 Charles Blattberg Part 2: The Practice of Rooted Cosmopolitanism 7 Cosmopolitanizing Cosmopolitanism? Cosmopolitan Claims Making, Interculturalism, and the Bouchard-Taylor Report / 129 Scott Schaffer Sample Material © 2012 UBC Press vi Contents 8 A World of Strangers or a World of Relationships? The Value of Care Ethics in Migration Research and Policy / 156 Yasmeen Abu-Laban 9 The Doctrine of the Responsibility to Protect: A Failed Expression of Cosmopolitanism / 178 Howard Adelman 10 Climate Change and the Challenge of Canadian Global Citizenship / 206 Robert Paehlke Contributors / 227 Index / 229 Sample Material © 2012 UBC Press Acknowledgments This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Canadian Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences, through the Aid to Scholarly Publications Programme, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Kathryn Walker’s work on this project was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, la Chaire du Canada en Mondialisation, citoyenneté, et démocratie at the Université du Québec à Montréal, and the Queen’s University Postdoctoral Fellowship in Democracy and Diversity funded by the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research. -

“A Microcosm of the General Struggle”: Black Thought and Activism in Montreal, 1960-1969

“A Microcosm of the General Struggle”: Black Thought and Activism in Montreal, 1960-1969 by Paul C. Hébert A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Kevin K. Gaines, Chair Professor Howard Brick Professor Sandra Gunning Associate Professor Jesse Hoffnung-Garskof Acknowledgements This project was financially supported through a number of generous sources. I would like to thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada for awarding me a four-year doctoral fellowship. The University of Michigan Rackham School of Graduate Studies funded archival research trips to Montreal, Ottawa, New York City, Port-of-of Spain, Trinidad and Tobago, and Kingston, Jamaica through a Rackham International Research Award and pre- candidacy and post-candidacy student research grants, as well as travel grants that allowed me to participate in conferences that played important roles in helping me develop this project. The Rackham School of Graduate Studies also provided a One-Term Dissertation Fellowship that greatly facilitated the writing process. I would also like to thank the University of Michigan’s Department of History for summer travel grants that helped defray travel to Montreal and Ottawa, and the Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec for granting me a Bourse de séjour de recherche pour les chercheurs de l’extérieur du Québec that defrayed archival research in the summer of 2012. I owe the deepest thanks to Kevin Gaines for supervising this project and playing such an important role in helping me develop as a researcher and a writer. -

Ma Major Research Paper the Role of Community Radio In

1 MA MAJOR RESEARCH PAPER THE ROLE OF COMMUNITY RADIO IN ENHANCING IDENTITY FORMATION AND COMMUNITY COHESION AMONG CARIBBEAN CANADIANS IN TORONTO NEIL ARMSTRONG Professor Charles Davis The Major Research Paper is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Joint Graduate Program in Communication & Culture Ryerson University - York University Toronto, Ontario, Canada August 2010 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Theoretical Framework 9 Theories of Identity Formation and Community Cohesion 20 Review of literature on alternative media 26 Methodology 30 Background of CHRY Radio 35 Background of CKLN Radio 42 Findings 43 Conclusion 63 References 65 Appendix A 71 Appendix B 72 Appendix C 74 3 Introduction Even as this research paper is being written, there is a news item on CBC Radio One that the Toronto-based, urban music radio station, Flow 93.5, has been sold to the CTV-owned CHUM-FM by Milestone Radio Inc. (Appendix A). Milestone Radio Inc., headed by Jamaica-born Denham Jolly, had struggled for a period spanning 12 years and three applications to the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) to own and operate a radio station. Many members of the Caribbean Canadian and Black communities wrote letters of support to the CRTC endorsing the application of Milestone Radio Inc. The radio station, Flow 93.5FM, was approved by the CRTC in 2000, signed on in 2001 and between then and now changed its programming to meet market demands. Many from the Caribbean Canadian community who supported the initial application of Milestone Radio Inc. -

Afrocentric Schools Within a Multicultural Context: Exploring

Ryerson University Digital Commons @ Ryerson Theses and dissertations 1-1-2008 Afrocentric Schools Within a Multicultural Context: Exploring Different Attitudes Towards the TDSB Proposal Within The lB ack Community Isabelle Ekwa-Ekoko Ryerson University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ryerson.ca/dissertations Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons Recommended Citation Ekwa-Ekoko, Isabelle, "Afrocentric Schools Within a Multicultural Context: Exploring Different Attitudes Towards the TDSB Proposal Within The lB ack Community" (2008). Theses and dissertations. Paper 82. This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Ryerson. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ryerson. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AFROCENTRIC SCHOOLS WITHIN A MULTICULTURAL CONTEXT: EXPLORING DIFFERENT ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE TDSB PROPOSAL WITHIN THE BLACK COMMUNITY by Isabelle Ekwa-Ekoko, BA, University of Toronto, 2004 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2008 Isabelle Ekwa-Ekoko 2008 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this major research paper. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this paper to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. ______________________________________ Signature I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this paper by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. -

Derailed: the History of Black Railway Porters in Canada Video Transcription

Derailed: The History of Black Railway Porters in Canada Video Transcription - Thank you everyone for joining us today for the quarantine edition of our Myseum Intersections program, "Derailed: The History of Black Railway Porters in Canada." My name is Joshua Dyer, I'm the director of marketing here at Myseum of Toronto. To be honest, usually I have a script that I follow for these introductions. However, I don't think we can have this discussion we're about to have today without reflecting on some of the recent events and protests over the past week that stem from racism and systemic violence against the black community. Our team here at Myseum is incredibly proud of the work we do in remembering, commemorating, honoring the histories of Toronto's diverse communities, and not shying away from the difficult conversations or difficult realities and injustices that are a part of our history. I personally feel that museums are not neutral spaces, in that we have a responsibility to educate ourselves and our audience and our community about past and present injustices. I believe we have a responsibility to amplify the voices of those that are victims to injustice, and we must listen to their stories, learn from their struggles, so that we can work together to uproot deep- seated iniquities that continue to exist in our society. It is only through confronting our past that we can chart a path forward. With that said, today's event is a Myseum of Toronto initiative presented with the support of the City of Toronto and the Ontario Black Historical Society. -

The Upper Guinea Coast in Global Perspective / Edited by Jacqueline Knörr and Chris- Toph Kohl

Th e Upper Guinea Coast in Global Perspective Integration and Confl ict Studies Published in Association with the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/Saale Series Editor: Günther Schlee, Director of the Department of Integration and Confl ict at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology Editorial Board: Brian Donahoe (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology), John Eidson (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology), Peter Finke (University of Zurich), Joachim Görlich (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology), Jacqueline Knörr (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology), Bettina Mann (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology), Stephen Reyna (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology) Assisted by: Cornelia Schnepel and Viktoria Zeng (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology) Th e objective of the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology is to advance anthropolog- ical fi eldwork and enhance theory building. ‘Integration’ and ‘confl ict’, the central themes of this series, are major concerns of the contemporary social sciences and of signifi cant interest to the general public. Th ey have also been among the main research areas of the institute since its foundation. Bringing together international experts, Integration and Confl ict Studies includes both monographs and edited volumes, and off ers a forum for studies that contribute to a better under- standing of processes of identifi cation and inter-group relations. Volume 1 Volume 7 How Enemies are Made: Towards a Th eory of Variations on Uzbek Identity: Strategic Choices, Ethnic and Religious Confl icts Cognitive Schemas and Political Constraints in Günther Schlee Identifi cation Processes Peter Finke Volume 2 Changing Identifi cations and Alliances in Volume 8 North-East Africa Domesticating Youth: Th e Youth Bulge and its Vol.I: Ethiopia and Kenya Socio-Political Implications in Tajikstan Edited by Günther Schlee and Elizabeth E.