Afrocentric Schools Within a Multicultural Context: Exploring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 2011 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium Panel with Cecil Foster

1 2011 Guelph Jazz Festival Colloquium Panel with Cecil Foster Writing Jazz: Gesturing Towards the Possible Interview conducted by Paul Watkins Transcribed by Elizabeth Johnstone Edited by Paul Watkins PW: So, this is the morning plenary. It’s more of an interview, a discussion of wits, somewhat dialogic, with Dr. Cecil Foster, who is a Canadian novelist. You may also know him as an essayist, journalist, and scholar. He was born in Bridgetown, Barbados, where he began working for the Caribbean News Agency. You can read his autobiography, which was published around 1998 and is called Island Wings, which describes his experience of growing up in Barbados and eventually emigrating to Canada, which he did in 1979. He worked for the Toronto Star, as well as the Globe and Mail. He was also a special advisor to Ontario’s Ministry of Culture. His most recent books, Where Race Does Not Matter, and Blackness and Modernity, explore the potentials for multiculturalism in Canada. Currently he is an associate professor of Sociology here at the University of Guelph, and hopefully today we’ll talk about multiculturalism, as well as improvisation, and how those intersections may relate to his own writing process. Without further ado I introduce Dr. Cecil Foster. CF: Good morning and let me say a special hello to all of my friends and colleagues, and people that will become friends and colleagues. It certainly is a pleasure to be here. I rather enjoy being here at Guelph. I have now gone through the ranks from assistant, to associate, to full professor, to end up being, one of the, I hope Ajay would consider me to be a writer. -

RHVP Pamphlet

MAKE THE RIGHT CALL! 9-1-1 www.torontopolice.on.ca EMERGENCY www.torontopolice.on.ca/ communitymobilization/ccc.php 416-808-2222 www.the519.org Police non-emergency www.primetimerstoronto.ca The Toronto Police Hate Crime Unit www.pridetoronto.com 416-808-3500 www.egale.ca www.black-cap.com Victim Services Toronto www.toronto.ca 24/7 Victim Crisis Intervention www.pflagcanada.ca 416-808-7066 www.soytoronto.org schools.tdsb.on.ca/triangle Crime Stoppers Toll-free: 1-800-222-TIPS (8477) “Hate-motivated crime is one of the most In Toronto: 416-222-TIPS (8477) heinous offences in society. The Toronto Online: www.222tips.com Police Service, in partnership with our www.ctys.org www.mcctoronto.com www.actoronto.org diverse communities, is committed to hate- crime prevention and to education regarding The LGBT Youthline patterns of behaviour which may lead to the commission of such crimes. I commend our Toll-free: 1-800-268-YOUTH (9688) community partners for their hard work and In Toronto: 416-962-YOUTH (9688) dedication in the area of education, crime Online: www.222tips.com www.camh.net prevention, helping people report crime, www.torontobinet.org and victim support. Your focus on youth is especially admirable.” The 519 Bashing Line William Blair, Chief of Police, 416-392-6877 Toronto Police Service www.transtoronto.com www.victimservicestoronto.com www.georgebrown.ca An initiative of the Toronto Police Service’s LGBT Community Consultative Committee FREEDOM FROM DISCRIMINATION WHAT TO DO AS VICTIM OR WITNESS? COMMUNITY RESOURCES AND HARASSMENT If you’re a victim of a hate crime, or of hate-motivated bullying, or Crime Stoppers: Your right to live, go to school, receive services, work and play in if you witness such acts, you should: Crime Stoppers is a community program and a partnership of the an environment free from discrimination and harassment on such • Stay calm, public, media, and police. -

Lgbtq Resources

Equity and Inclusive Education Resource Kit for Newfoundland and Labrador, Grades 7 -12 LGBTQ RESOURCES LGBTQ NewfouNdLaNd aNd LaBrador For a continually updated web directory of regional and national resources, see MyGSA.ca/Resources LGBTQ and LGBTQ-Friendly Organizations, Programmes, & Resources in Newfoundland and Labrador Provincial Resources: Making Queerness Visible Workshop 6 Camp Eclipse 7 Supportive Counseling and Peer Support (Planned Parenthood Newfoundland & Labrador Sexual Health Centre) 8 Wapanaki Two-Spirit Alliance, Atlantic Region 9 Piecing Together a Caring Community: A Resource Book on Dismantling Homophobia by Ann Shortall - selected sections available in PDF format at www.MyGSA.ca 10 Violence Prevention Labrador 10 Northern Committee Against Violence 10 Western Regional Coalition to End Violence 10 Southwestern Coalition to End Violence 11 Central West Committee Against Violence Inc. 11 The Roads to End Violence 11 Eastern Region Committee Against Violence 11 Burin Peninsula Voice Against Violence 12 Communities Against Violence 12 Coalition Against Violence 12 Resources in St. John’s: Aids Committee of Newfoundland and Labrador (ACNL) 13 Frontrunners (Running Group) 13 LBGT MUN (Memorial University) 14 LGBT Youth Group (Planned Parenthood & Newfoundland and Labrador Sexual Health Centre) 14 PFLAG Canada (St. John’s Chapter) 15 Spectrum (Queer Choir) 15 Resources in Corner Brook: Corner Brook Pride 16 Resources in Grand Falls-Windsor: LGBTQ Group in Central NL, Grand Falls-Windsor 16 Resources in Labrador: Safe Alliance, -

Supporting Families of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Youth: the Primary Care Team Approach November 10, 2017

Supporting Families of Transgender and Gender Non- Conforming Youth: The Primary Care Team Approach November 10, 2017 Thea Weisdorf, MD, FCFP, ABAM Sue Hranilovic MN, NP-PHC Giselle Bloch Conflict of Interest » Faculty/Presenter Disclosure: » Thea Weisdorf has no personal relationship with commercial interests Conflict of Interest » Faculty/Presenter Disclosure: » Sue Hranilovic has no personal relationship with commercial interests Conflict of Interest » Faculty/Presenter Disclosure: » Giselle Bloch has no personal relationship with commercial interests Program Disclosure of Commercial Support » We have no connections/support for development/presentation of the program from commercial entities or organizations including educational grants, in-kind AND no connections that a reasonable program participant might consider relevant to the presentation » Thank you to Rainbow Health Ontario, Hospital for Sick Children-Gender Identity Clinic for the use of components of their slide set (with permission) Mitigation of Bias: » We have presented many aspects of this workshop to our colleagues and communities and been provided feedback to ensure the mitigation of bias Worldview Recognizing our privileges and how they impact the lens through which we experience and navigate the world. Learning Objectives: 1. Increase awareness of gender dysphoria among Canadian youth 2. Explore the systemic, institutional, and individual barriers to accessing gender-safe health care for transgender and gender non- conforming youth 3. Identify the resources and research that validate the importance of family supports in promoting healthy outcomes Giselle’s Story Giselle’s Story Giselle’s Story Giselle’s Story Giselle’s Story Giselle’s Story Who am I today? Some Aspects of Transition • Social • Medical • Surgical Transition is an individual pathway. -

Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC

University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21,2005 18:30 Room 1714 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC AGENDA APPROVAL OF AGENDA REMARKS FROM THE CHAIR READING AND DISPOSING OF MINUTES OF THE SENATE MEETING OF May 17,2005. IV BUSINESS ARISING FROM THE MINUTES v READING OF ENQUIRIES AND COMMUNICATIONS VI QUESTION PERIOD VII CAUCUS REPORT VIII REPORTS OF STANDING BOARDS AND COMMITTEES 1. EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE page 11 For Information: Graduation Statistics BYLAWS & MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE page 15 For Action: Awards Committee Bylaw Amendment BOARD OF UNDERGRADUATE STUDIES page 21 For Action: (a) Bachelor of Bio-Resource Management - Proposal for a Major in Environmental Management (b) Bachelor of Arts - Economics - Deletion of Applied Economics Major (c) Bachelor of Science in Engineering - Changes to Admission Requirements (d) Bachelor of Applied Science, University of Guelph-Humber - Changes to Admission Requirements (e) Academic Schedule of Dates, 2006-2007 For Information: (0 Course, Additions, Deletions and Changes (g) Editorial Calendar Amendments (i) Grade Reassessment (ii) Readmission - Credit for Courses Taken During Rustication 4. BOARD OF GRADUATE STUDIES page 9 1 For Action: (a) Proposal for a Master of Fine Art in Creative Writing (b) Proposal for a Master of Arts in French Studies For Information: (c) Graduate Faculty Appointments (d) Course Additions, Deletions and Changes 5. COMMITTEE ON AWARDS page 177 For Information: (a) Awards Approved June 2004 - May 2005 (b) Winegard, Forster and Governor General Medal Winners 6. COMMITTEE ON UNIVERSITY PLANNING page 181 For Action: Change of Name for Department of Human Biology and Nutritional Science IX COU RE,PORT X OTHER BUSINESS XI ADJOURNMENT Please note: The Senate Executive will meet at 18:15 in Room 1713 Lifetime Learning Centre OVC just prior to Senate 1r;ne Birrell, Secretary of Senate University of Guelph Senate Tuesday, June 21": 2005 REPORT FROM THE SENATE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Chair: Al Sullivan <[email protected]~ For Information: Graduation Statistics - June 2005 Membership: A. -

Safely out Youth Booklet

S A F E L Y O U T LGBT Youth Resources TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE Out and Proud Program at CAST 2 Did You Know? 3 Common Myths 5 Definitions 7 Reasons to Come Out 10 Coming Out 11 When Someone Comes Out to You 17 Resources 19 “Out” on the Internet 21 Symbols of Pride 23 Acknowledgements 28 Safely Out 1 THE OUT AND PROUD PROGRAM AT THE CHILDREN’S AID SOCIETY OF TORONTO What We Do… Consultations and Referrals: As part of the Out and Proud program at The Children’s Aid Society of Toronto (CAST), experienced staff are available to meet with youth who may be questioning their sexual orientation or struggling with coming out. Staff can answer questions, offer support and provide referrals to outside agencies. 416-924-4640 ext 3055 or 3059. Life House Program: CAST has a series of residences for youth moving on from foster care towards independence. One of these residences is specifically designated for LGBT youth. Speak to your worker about a referral to this program. Training for Staff and Youth: Training for staff includes both a basic understanding of LGBT issues and more advanced “what-to-do-when” training to give a full understanding of how to deal with issues related to homophobia and coming out. Youth training involves bringing in peer educators to talk about the impact of homophobia and its relation to other oppressions. These programs are made possible by the generous support of our funders: The Children’s Aid Foundation, The Ontario Trillium Foundation, The Change Foundation, The Laidlaw Foundation, and The Lesbian and Gay Community Appeal. -

RESOURCES for LGBTQ YOUTH in TORONTO Updated Feb 2016 by CTYS

RESOURCES FOR LGBTQ YOUTH IN TORONTO Updated Feb 2016 by CTYS. This list is not exhaustive. See organizations’ websites for most current information. For more extensive listings of trans resources, see:”Resources for Trans Youth & Their Families” In-Person Services for Youth The 519 Downtown Toronto’s LGBTQ community centre, offering a variety of specialized programs and services. 416-392-6874. Pride & Prejudice Program - Central Toronto Youth Services Individual, group, and family counseling and services for LGBTQ youth (13-24). 416- 924-2100. Queer Asian Youth – Asian Community AIDS Services Workshops, forums, and social events for LGBTQ Asian youth (14-29). 416-963-4300 ext. 229. Queer Youth Arts Program – Buddies in Bad Times Theatre Free, professional training and mentoring for queer & trans youth (30 and under) who have an interest in theatre and performance. 416-975-9130. Stars @ The Studio - Deslile Youth Services A social drop-in space created by and for youth (13-21); an LGBTQ drop-in takes place monthly. 416-482-0081. DYS also provides a LGBT Youth Outreach Worker. Supporting Our Youth (SOY) – Sherbourne Health Centre In downtown Toronto, specialized programming for diverse LGBTQ youth (29 and under). 416-324-5077. The Triangle Program – Oasis Alternative Secondary School TDSB’s alternative school program dedicated exclusively to LGBTQ youth (21 and under). 416-393-8443. Sports & Fitness Outsport Toronto Serves and supports LGBTQ amateur sport and recreation organisations (see Listings) and athletes in the Greater Toronto Area. Queer and Trans Swim Night – Regent Park Aquatic Centre An “open and inclusive” swim time open to the public: Saturdays 8-9:30pm. -

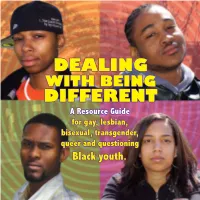

Dealing Different Dealing Different

DEALING WITH BEING DIFFERENT A Resource Guide for gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning Black youth. Content written by David Lewis-Peart, MSM Prevention Coordinator, Black-CAP Graphic design, illustration and photograhy by Frantz Brent-Harris • www.frantzbrentharris.com BLACK COALITION FOR AIDS PREVENTION The Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention (Black CAP) is a non-proft, community based, AIDS Service organization in Toronto that works with African and Caribbean people who are either infected or affected by HIV/AIDS. Black CAP’s mission is to reduce the spread of HIV infection within Black communities, and to enhance the quality of life of Black people living with or affected by HIV/AIDS. Black CAP accomplishes this mission through various programs and services offered by its Prevention, Education, Support, and Outreach departments. With funding from the City of Toronto – Access and Equity Program and the Community One Foundation, Black CAP chose to develop this resource booklet to help Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer and questioning (LGBTQ) Black youth and their families with the “coming out” process. Black CAP also wants to support youth struggling with issues about sexuality, and who are feeling disconnected from the support of family. Black CAP recognizes that as a result of this isolation, homophobia and rejection, many LGBTQ youth are at greater risk for HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted infections. In the process of creating this booklet, Black CAP consulted with, and gathered support from, a number of individuals and organizations. Special thanks to Supporting Our Youth – and the Black Queer Youth Group (BQY), staff and students at the Triangle Alternative School Program, our partners in the project, the African Caribbean Council on HIV/AIDS in Ontario (ACCHO), and fnally our funders at the City of Toronto and the Community One Foundation. -

Triangle Brochure

Information and Referrals To refer a patient to partial hospitalization, you may obtain prior approval from the patient’s insurance company before contacting the Intake Department, or we can do a level-of-care evaluation and contact the insurance company with information needed for authorization. Programming Tailored to To make a referral, call the Intake Department, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, The Triangle Program at 617-390-1320. Be sure to ask for The Triangle Program. Intake staff will schedule Intensive Behavioral Health Fit Your Needs a time for the patient’s arrival at the program and ask to have any appropriate clinical information faxed directly to us. Treatment for LGBTQ Adults HRI Hospital is accredited by The Joint Commission and licensed by the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health. The hospital also has a license from the Department of Public Health Bureau of Substance Abuse Services for both inpatient and outpatient treatment. We have immediate appointments available and accept most insurance plans. Affordable transportation should never be an issue in getting treatment. Please contact us for information. We know that seeking help can be overwhelming and we are here to support you. Our specialized partial hospitalization program treats adults with mental health and dual diagnosis issues. Group and individual therapy can provide you the tools you need to cope with life’s challenges. Treatment can include medication management offering you a comprehensive 227 Babcock Street, | Brookline, MA 02446 healing experience. Phone: 617-731-3200 | Fax: 617-566-0894 Our compassionate and caring staff hrihospital.com is here for you to provide the help Physicians are on the medical staff of HRI Hospital but, with limited you need. -

Addressing Homophobic Bullying in Schools Research Tells Us

September 2010 The Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat WHAT WORKS? Research into Practice A research-into-practice series produced by a partnership between the Literacy and Numeracy Secretariat and the Ontario Association of Deans of Education Research Monograph # 30 Homophobia threatens students’ educational achievement. How can we address this issue? Forging Safer Learning Environments Addressing Homophobic Bullying in Schools Research Tells Us ● Students are more apt to achieve By Dr. Gerald Walton academically in schools where they Faculty of Education, Lakehead University feel safe and supported. ● Students who are perceived as A Backgrounder on Bullying “different” are the ones who are most likely to be bullied, to the Students are more apt to achieve academically in schools where they feel 1 possible detriment of their educational safe and supported. The Ontario Ministry of Education recognizes that “safe achievement. schools are a prerequisite for student success and academic achievement” and is “committed to providing all students with the supports they need to learn, ● Homophobic bullying may be intertwined grow and achieve.”2 Bullying is a problem that undermines this commitment with bullying based on other forms of and erodes the potential for all students to prosper. social difference. Students who are perceived as “different” are the ones who are most likely to be ● Homophobic bullying is more prevalent bullied, to the possible detriment of their educational achievement. Difference among boys and young men. comes in many forms, such as race, religion, physical and mental ability, and class- based attributions (such as clothing and personal interests).These differences define the social categories that provide people with a sense of themselves and how they fit into society. -

Program Guide a Festival for Readers and Writers

PROGRAM GUIDE A FESTIVAL FOR READERS AND WRITERS SEPTEMBER 25 – 29, 2019 HOLIDAY INN KINGSTON WATERFRONT penguinrandomca penguinrandomhouse.ca M.G. Vassanji Anakana Schofield Steven Price Dave Meslin Guy Gavriel Kay Jill Heinerth Elizabeth Hay Cary Fagan Michael Crummey KINGSTON WRITERSFEST PROUD SPONSOR OF PROUD SPONSOR OF KINGSTON WRITERSFEST Michael Crummey Cary Fagan Elizabeth Hay FULL PAGEJill Heinerth AD Guy Gavriel Kay Dave Meslin Steven Price Anakana Schofield M.G. Vassanji penguinrandomhouse.ca penguinrandomca Artistic Director's Message ow to sum up a year’s activity in a few paragraphs? One Hthing is for sure; the team has not rested on its laurels after a bang-up tenth annual festival in 2018. We’ve focussed our sights on the future, and considered how to make our festival more diverse, intriguing, relevant, inclusive and welcoming of those who don’t yet know what they’ve been missing, and those who may have felt it wasn’t a place for them. To all newcomers, welcome! We’ve programmed the most diverse festival yet. It wasn’t hard to fnd a range of stunning new writers in all genres, and seasoned writers with powerful new works. We’ve included the stories of women, the stories of Indigenous writers, Métis writers, writers of different experiences, cultural backgrounds, and orientations. Our individual and collective experience and understanding are sure to be enriched by these fresh perspectives, and new insights into the past. We haven’t forgotten our roots in good story-telling, presenting a variety of uplifting, entertaining, and thought-provoking fction and non-fction events. -

July Justice, Our Church Lias Become a Donna Red Wing Ofthe Gill Foun 1973, the Gay Liberation Front Stronger Faith-Centered Body

Annual meeting mLOCAL AND STATE looks back at 2002 Empty Cioset unveils Chuck Bowen gives GAGV's vision for She future online edition website The Empty Ooset will go online just Chuck Bowen sketched his vision By Susan Jordan in time for Pride. The online ver for the future of the Alliance, de~ Approximateiy 100 people were sion of the paper can be found at scribing the areas to be covered by present at the Gay Alliance's an [email protected]. th« structural reo*-ganization: opera nual meeting at the Clarion River Advertising will eventually be sold tions/management, development, side Hotel on June 8 — coinci forthe online EC, and news articles community relations (programming) dentaliy, just about the same num^ can now l>e up<teted on a weekly or and communications. He noted that ber tfiat were present at the very daily basis. The GAGV website has the passage of SONDA will gjve the first meeting in 1973 of the group also been completely re-designed: that was to become the GAGV. Gay Alliance the task of educating visit www.gayalUance.org. Board member Evelyn Baiiey, k>cal businesses about how to be in Ribv* Ron HelvTts leaves who hmnds the 30th anniversary compliance with the state's new anti Ofsen Ai-ms ^fCC discrimination protections for Igbt celebration commit£e«, gave a On June 22, Rev. Ron Helms ended brief history ofthe Alliance, start people. SPECIAL PRIOE/HISTOilY ISSUE: Above: Our first cotor photo his seven-year ministry at Open ing with the events of Oct 3.